The X-Files was a show uniquely suited to its moment, one that, unfortunately, ran out before the show itself did. In the 1990s, conspiratorial thinking and a sense of a global slide toward chaos entropy could still be fun. Sept. 11 changed that somewhat, and so did the transfer of conspiracy thinking away from those who want to know what happened in Roswell and onto those willing to populate message boards with theories about the president’s true motives and nationality.

That makes the new adventures of Mulder and Scully, a 6-episode miniseries airing Mondays after a launch Jan. 24, feel unstuck from time. The series begins with Mulder (David Duchovny) reading a voice-over about everything that happened over the course of the series, which is not coincidentally the way that the Sex and the City movie began, too. After all, motivated writing would get us to care about Mulder’s quest to find the truth without quite so much exposition.

And exposition is what the new X-Files does best. A character in the season premiere played by Joel McHale draws Mulder and Scully into a new investigation simply by being himself—an Alex Jones-style conspiracy theorist whose line of work lends itself to trading long monologues with Mulder about the ills of the world. “They police us, and spy on us, and tell us that makes us safer,” Mulder announces at one point. “We’ve never been in more danger.”

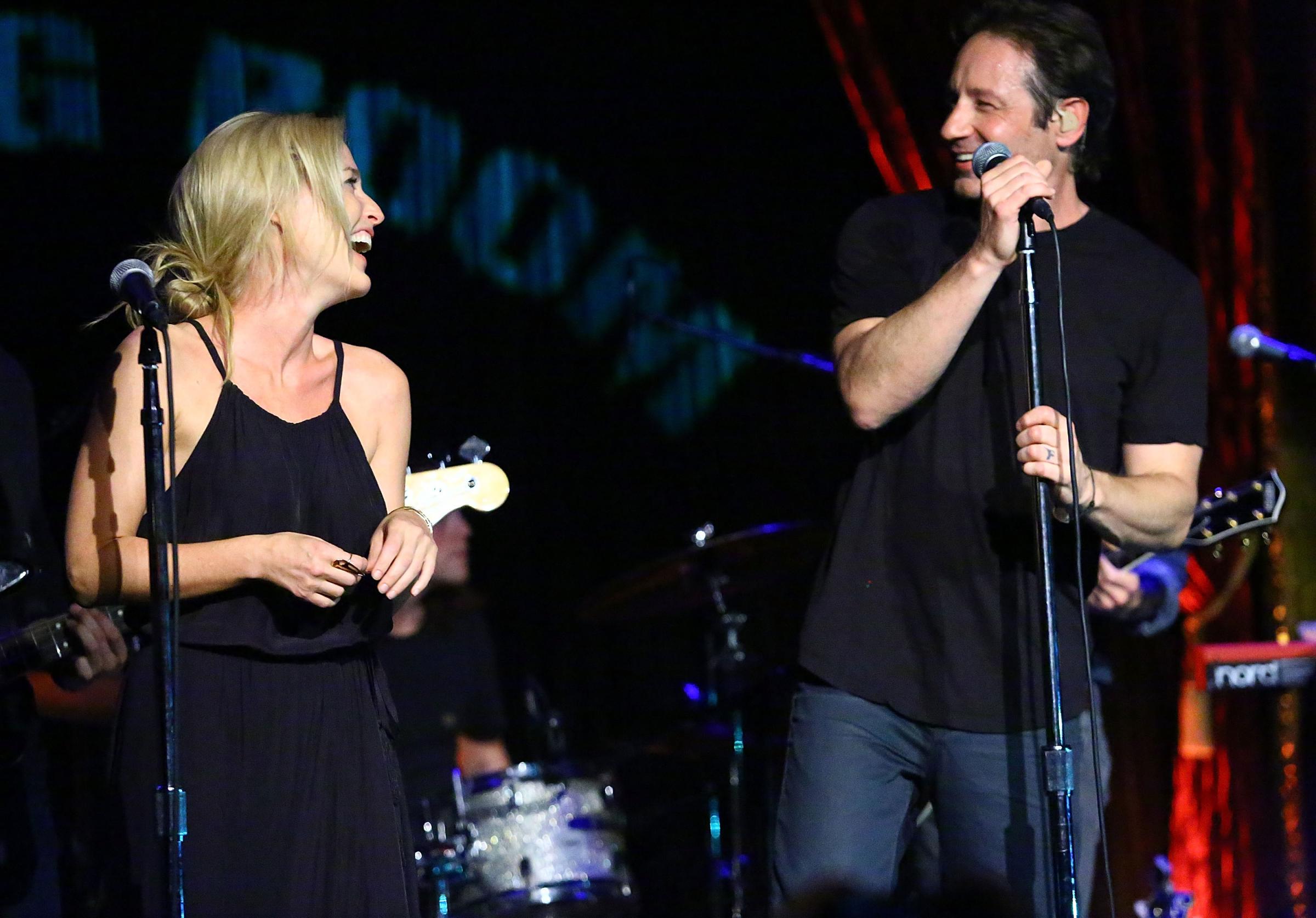

It’s worth noting that while Duchovny is declaiming, Gillian Anderson, as Scully, is sidelined; her plotline has her abandoning a new life as a surgeon to re-team with Mulder, but she feels less like the equal partner she always was than like an adjunct or occasional hang-out buddy. It’s a strange missed opportunity to fully use an actress who’s so able to sell bad material—her reply to the question “Do you miss it all… the X-Files?” is the new season’s most beautifully acted—but makes sense. Scully, a skeptic, was the key that made the tension of old X-Files run; she and Mulder would have it out over each new file. The new episodes, racing to keep up with a reality in which anything seems possible, give Mulder the win each time without even token opposition.

See the Evolution of Mulder and Scully From 'The X-Files'

There’s no way for a show as pulpy and self-consciously fun as The X-Files to make hay out of what really feels awry about the contemporary world, so the writers alternately choose lecturing (and reaching back into the distant past, as with a cutaway to George W. Bush used to illustrate the ills of government-urged consumerism) and going off in a completely random direction. The “monster of the week” episodes of The X-Files were a major part of that show’s success, and were great fun. This time around, the big monster-of-the-week episode builds to a pretty predictable joke, buttressed with a weird motif involving a transgender prostitute who meets a monster. The episode, even aside from its jokes about the transwoman’s drug use, plays things so slangily loose that it ended up inadvertently (or not) implying that trans people are, themselves, monsters.

That’s an unforced error—no one was waiting for The X-Files’s take on the trans experience—but it speaks to the ways in which society has gotten too complicated for The X-Files to exist. 2016 may be the worst possible time to attempt a reboot of a series whose point of view was that conspiracy theories are, above all else, fun. As evidenced in political polling, the current national mood is something less joyful and more fearful, and a show in which a can-do attitude can barrel through any mystery feels out-of-step with the times.

That doesn’t stop The X-Files from trying. The show, after all, has to live down an ending that resolved little and a stand-alone movie, in 2008, that underperformed at the box office (it was overshadowed by a film that spoke far more strongly to the national mood at that time—Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight.) And it exists in a TV ecosystem where everything from Full House to 24 and Prison Break is coming back, no matter their relevance to what TV viewing, or the cultural scene at large, is like now. One stumbling-block in its attempt, aside from the times, is the show’s length. Perversely, I wish there were more new X-Files if there were to be any at all; the season promises to get at mysteries it doesn’t seem as though it’ll have time to solve.

But then, The X-Files at its best wasn’t about overarching mysteries (or so it seems in retrospect, now that we know they weren’t ever satisfyingly solved). It was about the friendly chemistry between the two stars, which persists despite Anderson’s marginalization—like finds a way. And it was about the adventurous places the show’s writers were willing to go. But Mulder’s suspiciousness feels, now, like a dull stating of something close to conventional wisdom, and the show’s mysteries lack the spark they once had. The great success of The X-Files’s paranoid vision may be that its popularity made a series revival feel, ultimately, behind the times.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com