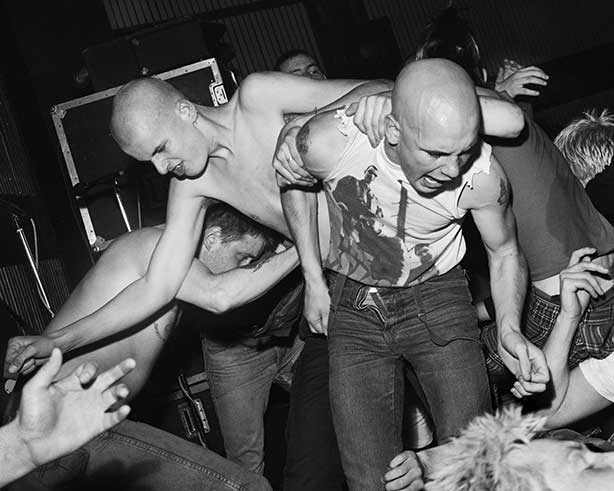

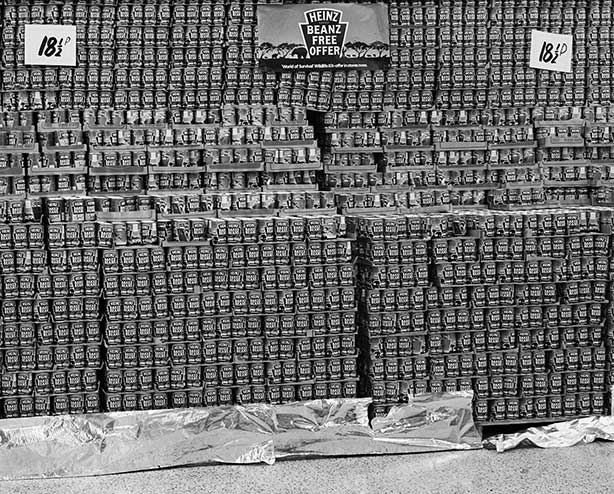

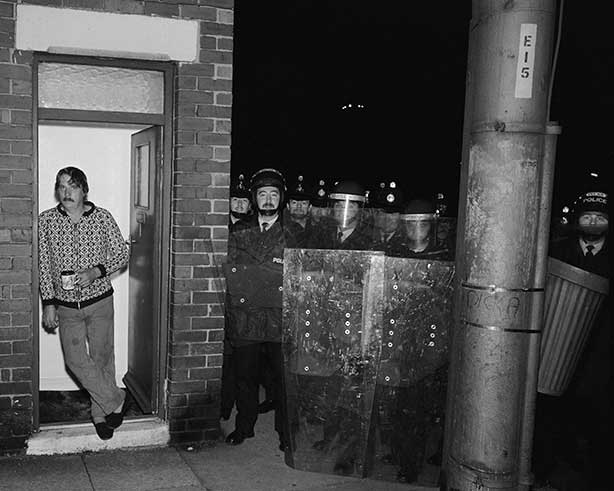

Since its publication in 1988, Chris Killip’s In Flagrante has been hailed as a masterpiece of photojournalism – a book that not only influenced many of Killip’s contemporaries but also came to be defined, wrongly, says the photographer, as a savage criticism of Margaret Thatcher’s years as U.K.’s Prime Minister.

Twenty eight years later, In Flagrante is getting its first reprint, courtesy of Steidl. In Flagrante Two, which got its name after Killip made the decision to add two photographs to the original sequence, is, in many ways, a different book – one benefits from three decades of hindsight, says Killip.

To celebrate the In Flagrante‘s reprint, as well as the Yossi Milo Gallery show that accompanies it, TIME LightBox asked photographer Martin Parr – an avid collector of Killip’s prints – to discuss the book’s legacy and rebirth with its author.

Martin Parr: You have said before that you would never re-do In Flagrante. What made you change your mind?

Chris Killip: When In Flagrante first came out I got a letter from [British photographer] Brian Griffin saying, “I always knew that you were very fond of the gutter but I had no idea that you’d end up in it.” I also got a less witty letter from [South African photographer] David Goldblatt expressing his annoyance at my decision to “cross the gutter”. I can’t remember much about the reviews of In Flagrante but I never forgot the letters from Brian and David.

When the Errata edition [which presented a facsimile of the original book] came out in 2008, it started me thinking again about In Flagrante and the issue over my use of the gutter. Thoughts just started to percolate. Going back to look at the original book startled me as the reproduction now looked rather grim, far too heavy in the blacks with a consequent loss of detail. At the time –1988 – the printing was the best that could be done in England.

The Errata edition also started me rethinking and while I had always turned down the offers to do a facsimile edition I now did want to do something. In 2014, I started playing around with ideas and realized that I had some basic aims in mind if I was to do anything:

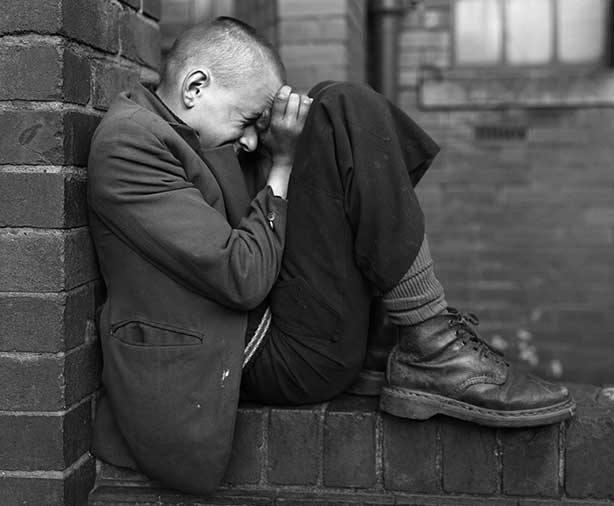

Sarah Kent in Time Out reviewed In Flagrante when it came out, saying about the image, Youth Jarrow, “that this man in his Doc Martin boots and in his despair encapsulates the Thatcher Years”. When something goes into print, it can stick despite the fact that this was obviously a photograph of a schoolboy – just look at his worn school pants and jacket, he’s just cold. What I thought was self-evident wasn’t evident to Kent. Susan Kismaric’s title “The Thatcher Years” for the Museum of Modern Art show added to this simplistic journalistic classification.

I worked on a dummy of the book during 2014, figuring out the image size and I also thought about the original texts. I still liked the John Berger and Sylvia Grant text that introduced the book in the way that its an oblique commentary, but I didn’t want to use the William Butler Yeats poem or my short text. It was a good moment when I decided to start with the Len Tabner painting image as it was a good substitute for the Yeats text as I felt in reality that he was painting his dreams with the addition of all those seagulls in this drama when in fact it was far to windy for them to fly. The image was also a very good comment on photography and its very distinct relationship with reality.

Strangely it took quite a while to come up with the one sentence of factual text, which reads:

“The photographs date from 1973 to 1985 when the Prime Ministers were: Edward Heath, Conservative (1970-1974), Harold Wilson, Labour (1974-1976), James Callaghan, Labour (1976-1979), Margaret Thatcher, Conservative (1979-1990).”

This text is followed by a page of thumbnails of the images with their location titles – something that’s not in the original edition.

When I figured this out I decided to drop the Berger/Grant text and just rely on the historical facts.

I made the dummy images digitally and they were very high quality and I started thinking how important this quality was and as I was only using the right hand page there was no see-through coming on to another image. If the reproduction was good enough and enough space was left around the image you could just cut them out and frame them, I very much liked this possibility.

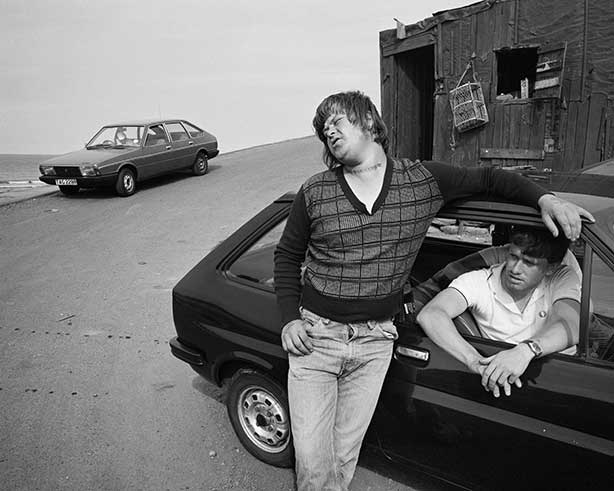

The book is very unadorned, it had become very important to me to let the images speak without interference, as I believe that they have their own eloquence and in some cases a degree of ambiguity – a mixture that leaves the work open to interpretation by the viewer.

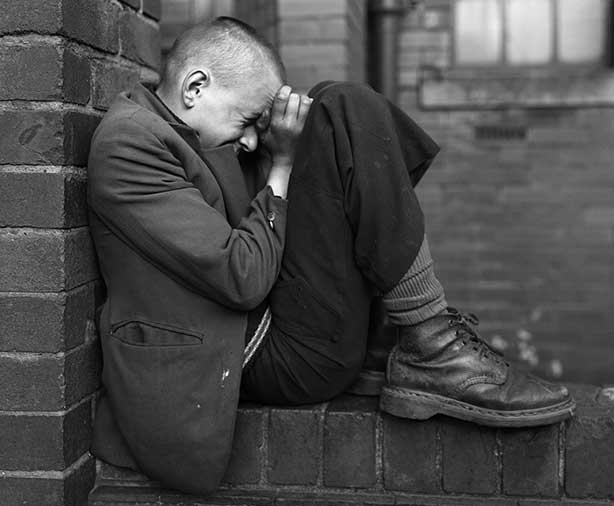

I also added new images, two of which are very helpful in contextualizing the work without using explanatory text. The image following these is of a working class-terraced housing in Wallsend, with the third image from the end showing the same housing being demolished, acting as an obvious comment on deindustrialization as well as context.

The Bobby Sand image with the graffiti “Bobbie Sands greedy Irish pig” was taken on the day Mrs. Thatcher announced his death and, hopefully, serves the book well with its historical/political/social context.

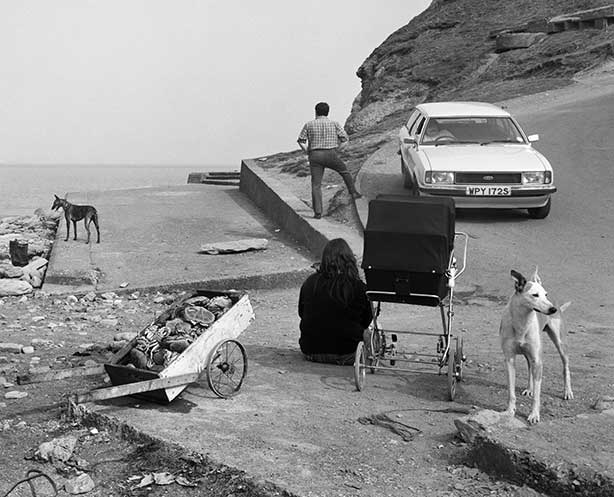

The dust jacket images, Torso, Gateshead, on front and Crabs and people, Skinningrove, on the back were suggested by Victor Balko, the designer at Steidl. It’s an interesting combination as no faces are depicted – to see them you have to open the book. The first face you see in close is six pages into the book and it’s Youth Jarrow.

Martin Parr: One thing that has emerged since its first publication, and this is reflected in the high price it now commands, is that people now know what a great book and body of work it is. Would you agree with the statement that it is your finest achievement, and do you think In Flagrante Two makes it even better?

Chris Killip: It’s certainly perceived as my finest achievement. In Flagrante Two is different. Better? We will have to see what the jury makes of it. I was 42 and living in England when In Flagrante came out and when In Flagrante Two comes out I will be 69 having spent the last 25 years living and teaching in the U.S. Maybe that’s the big difference, 28 years of hindsight.

Martin Parr: Did you ever consider re-visiting the area that In Flagrante was shot in? I know you did not return with your camera. What are the reasons why you have not shot in the U.K. for all of these years, and why did you chose Ireland instead?

Chris Killip: I’m still in touch with the sea-coalers that I was big friends with and I’m up to date with how they are doing now that they have moved away from the area. The sea-coal camp has gone, so have the coal mine and the power station. The area has been landscaped and now looks like an unused golf course. You would never know that the sea-coal camp had existed.

I went back to Skinningrove three years ago and that was a big shock as it was so quiet as only two boats do any fishing from there. Everyone else has stopped as they couldn’t keep up with European Economic Community and Health and Safety regulations. It was as if all the life had gone out of the place.

I went to Ireland in 1991 to teach a photo-workshop on the Aran Islands for Christine Redmond and the Gallery of Photography, Dublin. I was going to Harvard in September of that year and thought it would be a good teaching experience. I had never been to Ireland before and liked it a lot. So I came back to do a workshop each summer and spent time traveling and photographing there. The Irish book [Here Comes Everybody] came out of this. I was very involved with Harvard at that time and it was a great relief to be in Ireland, it had a civilizing effect on me.

I find the idea of photographing in England quite difficult. The areas that I photographed and that I’m interested in are in the North of England and have very much declined since my time there, with the loss of coal mining, shipbuilding, steelworks and most industries. I’m very glad I photographed when I did. A lot of the communities that I was interested in were very industry specific and without that industry they are in a sort of limbo having lost their purpose and their dynamic.

Martin Parr: Could you ever imagine living in the U.K. again?

Chris Killip: After living in the U.S. for 25 years I don’t think that it’s likely that I will ever return to Britain to live but I very much enjoy visiting and do so two or three times a year.

Chris Killip‘s In Flagrante Two is published by Steidl. The corresponding show at the Yossi Milo Gallery in New York runs until Feb. 27, 2016.

Martin Parr is a British photographer represented by Magnum Photos.

Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com