They remind me of the Dirty Dozen. Except there are more than twelve of these guys. And they look more badass.

In that classic 1967 war movie, the Allies recruit twelve scarred convicts for a mission to parachute behind enemy lines and kill Nazis. The Allied command figures these murderers are the best men to murder murderers—and they don’t care if the men ever come back.

Read More: How the Mexican Drug Trade First Began

In 2014, the Mexican government made a similar calculation: It decided that gangsters were the best people to take out gangsters. In the Pacific state of Michoacán—one of the most violent and crime-ridden in the country—it formed an elite squadron with the job of hunting down leaders of the bizarrely named Knights Templar cartel. The unit was nominally part of a Rural State Force created that year to deputize vigilantes fighting the traffickers. But full-on mob assassins also jumped in, apparently to help take out their rivals. Many hailed from a gang known as Los Viagras in the market town of Apatzingán, a hub of drug traffickers. Others came from mountain villages nestled amid marijuana and opium fields.

On Sept. 4 of that year, I find about 50 members of the squadron milling around a parking lot at the entrance to Apatzingán. They are comparing weapons and getting ready for a mission to storm through villages on a missing to find Knights Templar leader Servando Gómez, alias “La Tuta.” They are seriously tooled up. Supposedly, the Rural Force are only allowed to carry government-issued AR-15 rifles. But who cares? The squadron here has everything up to huge G3 machine guns, which the Mexican army also uses.

They refer to their weapons by farmyard names, which is fitting because Michoacán is a fertile agricultural state. They call fifty-caliber bullets jabalitos, or “little boars.” Their beloved Kalashnikovs are “goats’ horns”— because of their curved ammunition clips. However, to turn the AK-47 into a really lethal machine, they use circular clips with a hundred bullets. When you spray a hundred caps in ten seconds you have a pretty good chance of hitting your target, and anybody close by. They call the circular clips huevos, or “eggs.” A lot of them carry grenade launchers, mostly fixed to their rifles. They call the grenades papas, or “potatoes.” They tape grenades and ammo clips round their waists and across their chests, giving them the look of authentic desperadoes.

Read More: The Actor, the Kingpin, and Mexico’s Drug War as Entertainment

The gangsters also show me their personalized sidearms. The pistols are decorated in diamonds and other stones with classic narco designs. One of them has El Jefe—“The Boss”—engraved into his pistol. He asks if I take “ice,” the name they use for crystal meth. (I say I don’t.) The Michoacán mob churns out meth by the ton, providing for tweakers from Kentucky to California. “El Jefe” remarks how pure the local ice is. DEA agents have told me that they agree. They say that Michoacán meth is the purest they have ever found.

I take photos of the guys with their weapons. They do battle poses. The two-meter-tall guy tells me not to take his picture. I say that is fine. Then another man in his late forties appears from nowhere and points his finger at me. He accuses me of being a DEA agent.

“He is DEA. Why is he taking photos?”

I assure him that I am a journalist and I try to shake his hand. He refuses. “The DEA busted my brother in Texas,” he growls. “The agent was posing as a journalist.” The atmosphere changes in a flash. I tell him that I am not even American. I’m British. I point out a website that features my work. El Jefe finds it on his smartphone. My accuser relaxes a little and turns to me.

“If I see you again, I am going to put a bullet in your head.” He taps his forehead with his finger and points at me. To make sure the message gets across, he adds, “I’ll throw a papa [grenade] at you.”

I do my best to smile.

***

Back in the 1970s, hit men from Mexico to Brazil used to be assassins who killed quietly in the black of night. Now they have transformed into commandos with light infantry weapons, even shoulder-held rocket launchers. A band of traffickers called the Zetas even build their own tanks, which look like something from the fantasy road wars of Mad Max. They pour into towns in convoys of 30 pickups to massacre terrified residents. They attack soldiers in ambushes, opening fire with fifty-caliber rifles. In many cases, they use the same battle tactics as Latin America’s old guerilla armies.

Read More: How the Mafia Makes Millions Out of the Plight of Migrants

The leftist guerrilla was an emblematic symbol of Latin America in the twentieth century, personified in the iconic photos of Che Guevara. In the new millennium, guerrillas have disappeared from most of the continent. The growth of democracy has allowed former radicals to become politicians, even presidents. The idea of establishing Marxist dictatorships has been discredited. Some of the remaining guerrillas, like the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia or FARC, have become major cocaine traffickers.

But where the beret-wearing freedom fighters have disappeared, cartel armies have risen. Tragically, the cartel sicario with a Kalashnikov is a more dominant symbol of the new Americas. Far more young people idolize Chapo Guzmán— the billionaire drug trafficker caught on Jan. 8 — than Che Guevara.

The new generation of kingpins from Mexico to Jamaica to Brazil to Colombia are no longer just drug traffickers, but a weird hybrid of criminal CEO, rock star and paramilitary general. They fill the popular imagination as demonic antiheroes. Not only do they feature in underground songs in the drug world—they are re-created in telenovelas, movies, and even video games simulating their new warfare.

And what they do affects us all. Over the last two decades, these crime families and their friends in politics and business have taken over much of the world’s trade in narcotics, guns, even people, as well as delved into oil, gold, cars and kidnapping. Their networks stretch throughout the United States into Europe, Asia and Australia. Their chain of goods and services arrives at all our doorsteps.

Like guerrillas, drug cartels are deeply rooted inside communities. As Mao Tse-tung famously said, “The guerrilla must move amongst the people as a fish swims in the sea.” Gangster militias also draw their strength from villages and barrios. As in counter-insurgency campaigns, governments get frustrated confronting an enemy they can’t see and unleash soldiers to torture and murder civilians, trying to take away the sea from the fish.

But this comparison with insurgents does not mean that gangster gunmen will act in all ways like traditional guerillas or should be treated in the same way. Many Latin Americans see insurgents as the honorable fighters who liberated their land from the tyrants of the Spanish Empire. They view cartel hit men as demons. A traditional insurgent believes in their vision of a greater good, whether inspired by Marxism, Islam or nationalism. The gangsters are chiefly motivated by just one god— mammon, the green of dollars bills. The strategic objectives of the bloodshed also differ. Guerrillas usually try to topple governments and take power. Cartel gunmen often attack security forces to pressure governments to back off.

A central objective of the gangster gunmen is to control their fiefs. If the government threatens them, they may launch insurgent-style attacks.To back these up, they often claim to be fighting for the poor. But in other cases they cut deals with governments, or directly control them. They can help the powerful fight their enemies and give them a share of their spoils, working like a paramilitary.

Conflict has transformed around the world since the Cold War. Warlords have left mounds of corpses in Africa from Liberia to Uganda. While they differ from the gangsters of the Americas in many ways, they also use ragtag armies with barbaric tactics alongside new technology. And they also base their power on the control of fiefdoms.

Militant Islamists are a very different—and much bigger—threat than the gangsters of the Americas. The Islamic State showed that it can control territory the size of a country. But you can’t help but find similarities with the cartels. In 2012, the same year the Taliban beheaded 17 people at a wedding in Afghanistan, shocking the world, the Zetas left the bodies of 49 headless victims in Mexico. When the Syrian regime first wanted to demonstrate the horrors that Islamic rebels were committing, it couldn’t find any footage, so it showed video that turned out to be by Mexican cartels. (It soon had plenty of its own to show.) Islamic radicals and gangster militias both recruit poor lost teenagers and train them to be murderers; they both fight with small cells and ambushes. And in both cases, Washington is flummoxed on how to deal with them.

A Mexican cartoonist summed up the common ground following the 2015 attack on French magazine Charlie Hebdo. His cartoon showed a picture of a masked man with an AK-47. “Ahhhhh. It’s an Islamic terrorist,” says one voice. “Tranquila, tranquila,” says another. “It’s just a hit man from the Gulf Cartel.”

Gangster warfare has ravaged the Americas, paradoxically, even as many nations in the region appeared to be getting freer and wealthier. The Cold War, which had been a hot conflict in much of Latin America, was over, with the U.S. declaring victory. Dictatorships collapsed, giving birth to young democracies. Borders opened up to free trade, governments liberalized their economies, and Francis Fukuyama declared “The End of History.”

But as we look back on the last two decades, we can identify clear causes of the new conflicts. The collapse of military dictatorships and guerrilla armies left stockpiles of weapons and soldiers searching for a new payroll. Emerging democracies are plagued by weakness and corruption. A key element is the failure to build working justice systems. International policy focused on markets and elections but missed this third crucial element in making functional democracies: the rule of law. The omission has cost many lives.

The deregulation of economies created some winners while leaving swathes of the world’s slums and countrysides in poverty. Meanwhile, a global black market in contraband, human trafficking and guns has expanded exponentially.

Narcotics are the biggest black market earner of all. Estimated to be worth more than three hundred billion dollars a year, the global industry has pumped huge resources into criminal empires decade after decade. It has had a cumulative effect, heating up the region to a boiling point. The brutal logic of the underworld is that the most terrifying gangsters get the lion’s share of the profits, leading to the ultimate predators such as the Zetas.

But this violence is raging during a historic turning point in the drug debate. Four U.S. states and Washington, D.C., have legalized marijuana along with the entire country of Uruguay. Politicians across the continent have come out of the closet to criticize the war on drugs. Actors and musicians line up to join the cause of drug policy reform.

Yet while the debate has transformed, the old policies largely stumble on. The U.S. spends billions on DEA agents in 60 countries and bankrolls armies to burn crops from the Andes to Afghanistan. Most narcotics remain illegal and keep providing massive profits to those violent enough to claim them. The next task is to move from a change in the debate to a change in the reality on the ground.

The web of crime cartels stretches across the hemisphere, leading to all kinds of unlikely places. It affects lime prices in New York bars, British secret agents, World Cup soccer stars, bids to hold the Olympic Games, questions over the start of the London riots. In the summer of 2014, it was linked to 67,000 unaccompanied children arriving at the U.S. southern border, fleeing cartel crime in Central America and triggering what President Barack Obama called a humanitarian crisis. Less publicized were the tens of thousands of adults from the region arriving on the southern border asking for political asylum.

Some people ask why it matters if neighboring countries fall to pieces. This is one of the reasons.

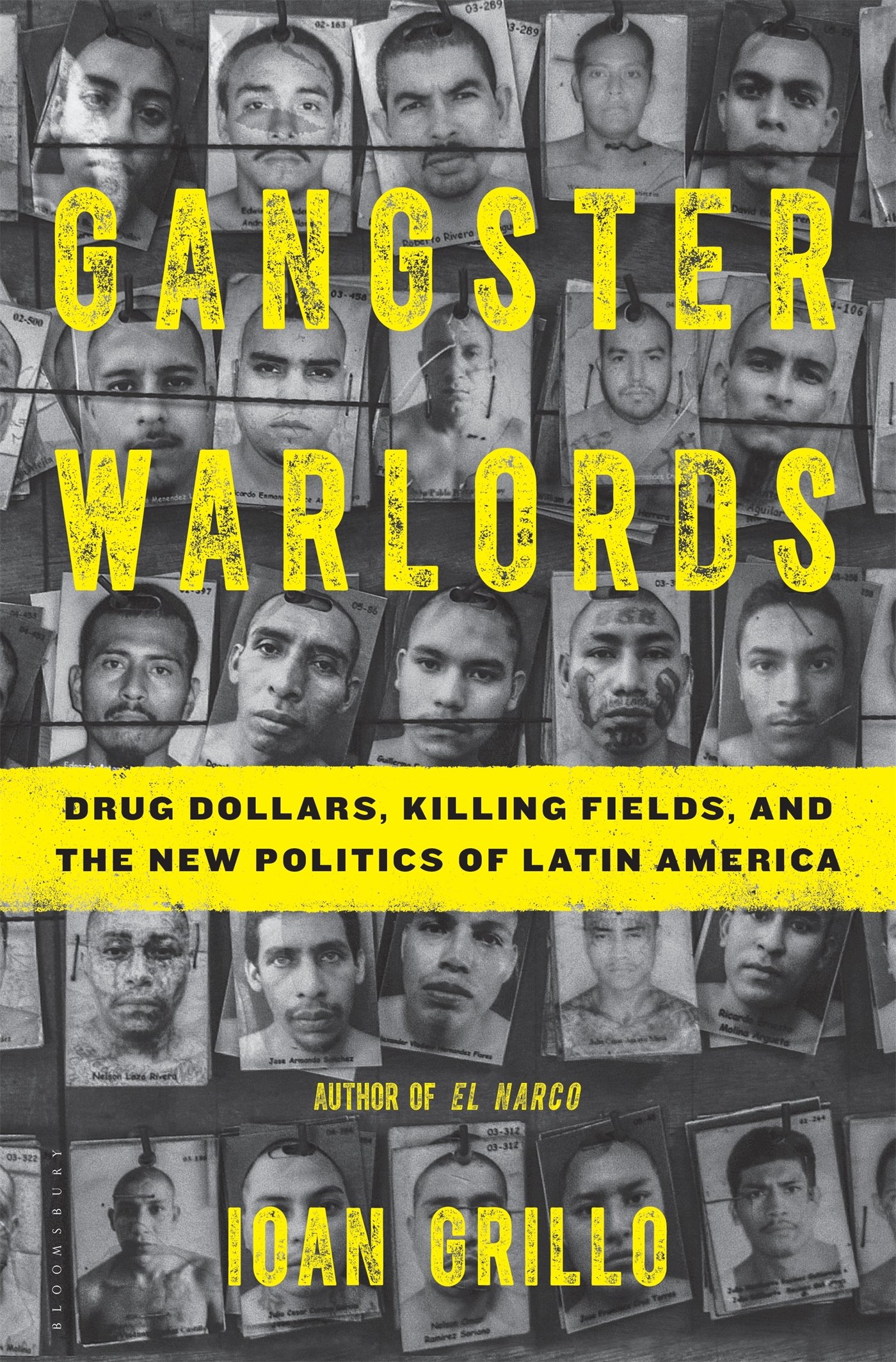

An excerpt from “Gangster Warlords: Drug Dollars, Killing Fields and the New Politics of Latin America,” released in the United States today and published by Bloomsbury.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com