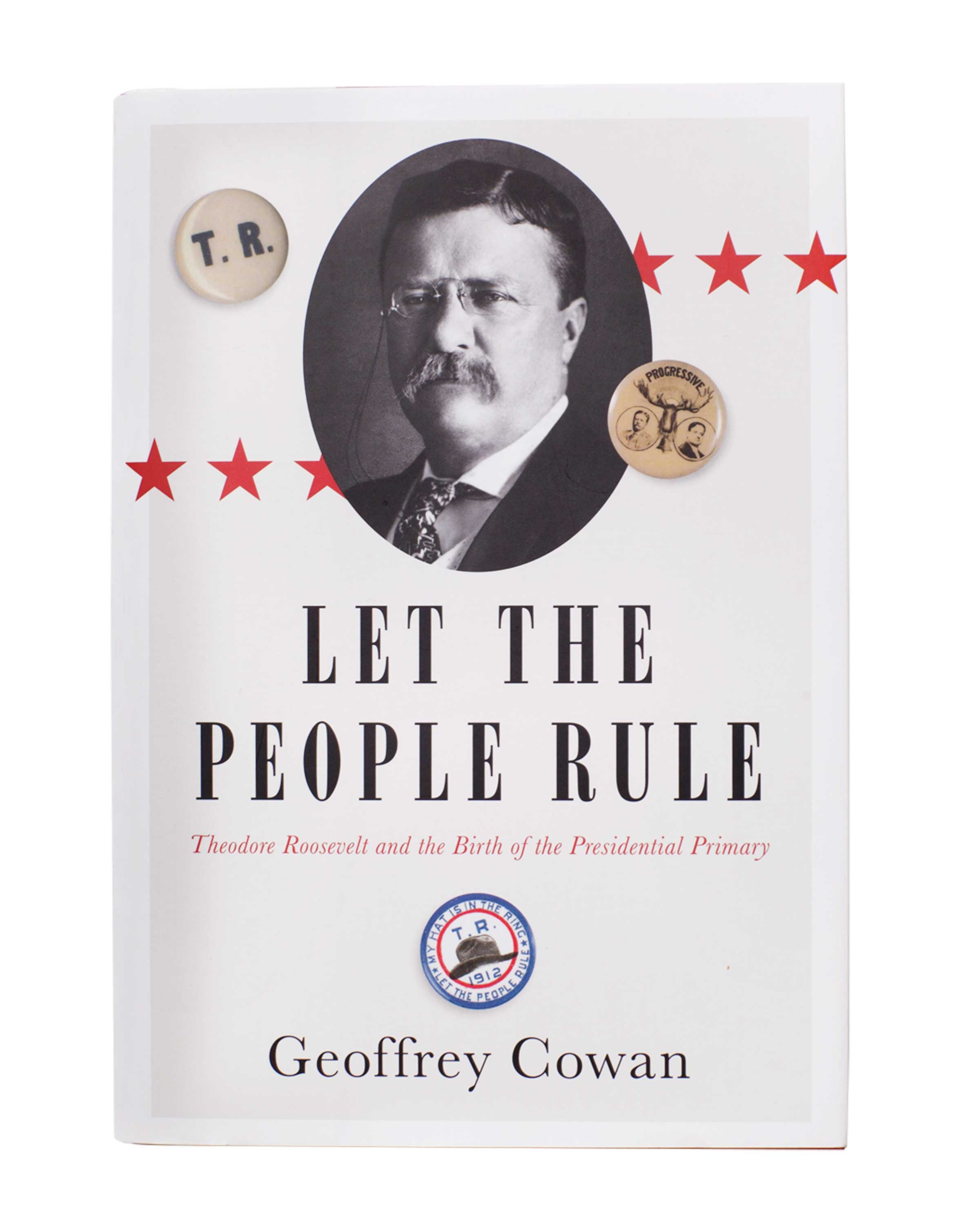

In 1968, Geoffrey Cowan’s efforts as a young campaign worker failed to get Eugene McCarthy to the White House but succeeded at a perhaps larger task: changing how the Democratic National Convention picked delegates. Now, in his new book, Let the People Rule, he traces that primary system to its start.

It’s a complicated story that Cowan keeps lively, mostly avoiding the he-said-he-said of old-timey politicking, but readers who dive in for a feel-good story of how Americans got to choose their parties’ nominees may end up depressed if enlightened.

As the 1912 election neared, some Republicans were unhappy with incumbent President Taft. But it was unlikely that the party would pick a different nominee–not even Teddy Roosevelt, the popular ex-President whose charisma Cowan renders palpable. So Roosevelt encouraged states to set up primaries, as a potential win-win: more democratic than letting the local party machine choose convention delegates and a way for the people to pick Roosevelt even if the party wouldn’t. As Cowan writes, “We often define democracy in ways that suit our own desired outcomes.” That March in North Dakota, with the first direct presidential primary, a new path for candidates was introduced. It has endured for more than a century.

But so has institutional power. The Republican National Committee controls its debate schedules; the Democratic National Committee controls access to its voter data. And as history knows, popular opinion was no match for party bosses in 1912. The Bull Moose Party, founded by Roosevelt in response to Taft’s convention victory, was no different. The most affecting section of Cowan’s book depicts Roosevelt’s camp debating how to treat black Southerners, who leave the party of Lincoln in hopes that the new party will be more inclusive, only to see Roosevelt’s supposed populism subsumed by political calculations.

In these cases, questions were settled by the decisions of those who could rewrite the terms of the debate. It’s the political process as Hunger Games: no matter which tribute emerges as victor, the Gamemaker has the power. Teddy Roosevelt changed the system and still couldn’t beat the odds.

But another Roosevelt could. Patricia Bell-Scott’s The Firebrand and the First Lady portrays the unlikely, largely epistolary friendship between Eleanor Roosevelt and Pauli Murray. Murray was one of the few black residents at a New Deal camp for women in upstate New York when she encountered the First Lady. She later became a high-achieving lawyer, author and civil rights activist, and a real friend to Roosevelt.

The book is slighter than Cowan’s and occasionally feels fragmented, as Bell-Scott follows Murray from job to job, but it might do wonders for those feeling politically disenfranchised.

This Roosevelt had no desire to hold office, so she was able to follow her beliefs. Murray played a role in her evolution, and vice versa. Institutions still presented mighty barriers. Harvard Law rejected Murray on the basis of her sex, for example, and not even the White House could help. But Murray and Roosevelt were pros at moving forward, especially when they did so together.

These days “Some of my best friends are black” is a laughable response to accusations of racism, but not so in 1953, when Roosevelt wrote an essay in Ebony magazine called “Some of My Best Friends Are Negro.” Those friends, Murray among them, offered hope that equality was possible. Even if the people can be ruled, the power of one person is abundantly clear.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com