This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

Sean Penn, actor and activist, has made a name for himself as something of a renegade journalist, pursuing interviews with controversial figures such as Cuban leader Raul Castro, the late Venezuelan strongman Hugo Chavez, and most recently Mexican drug kingpin Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman. Penn’s interview with El Chapo is perhaps his most provocative, for the narcotics trafficker has been America’s most wanted man since the death of Osama bin Laden in 2011. While the interview, printed in Rolling Stone, is certainly intriguing, it is important to remember how much of a point of contention the war on drugs has become for the United States and its southern neighbor. Since the 1960s, relations between the U.S. and Mexico have grown increasingly strained due to not only the growing presence of drug cartels in Mexico, but the seemingly endless flow of firearms south and the insatiable American appetite for marijuana, heroin, and cocaine. As the U.S. and Mexico negotiate the extradition of the world’s most powerful drug trafficker from his home base in Sinaloa state to a correctional facility somewhere north of the border, distrust between the two countries remains palpable, particularly after El Chapo’s previous escapes from two out of Mexico’s three maximum security prisons.

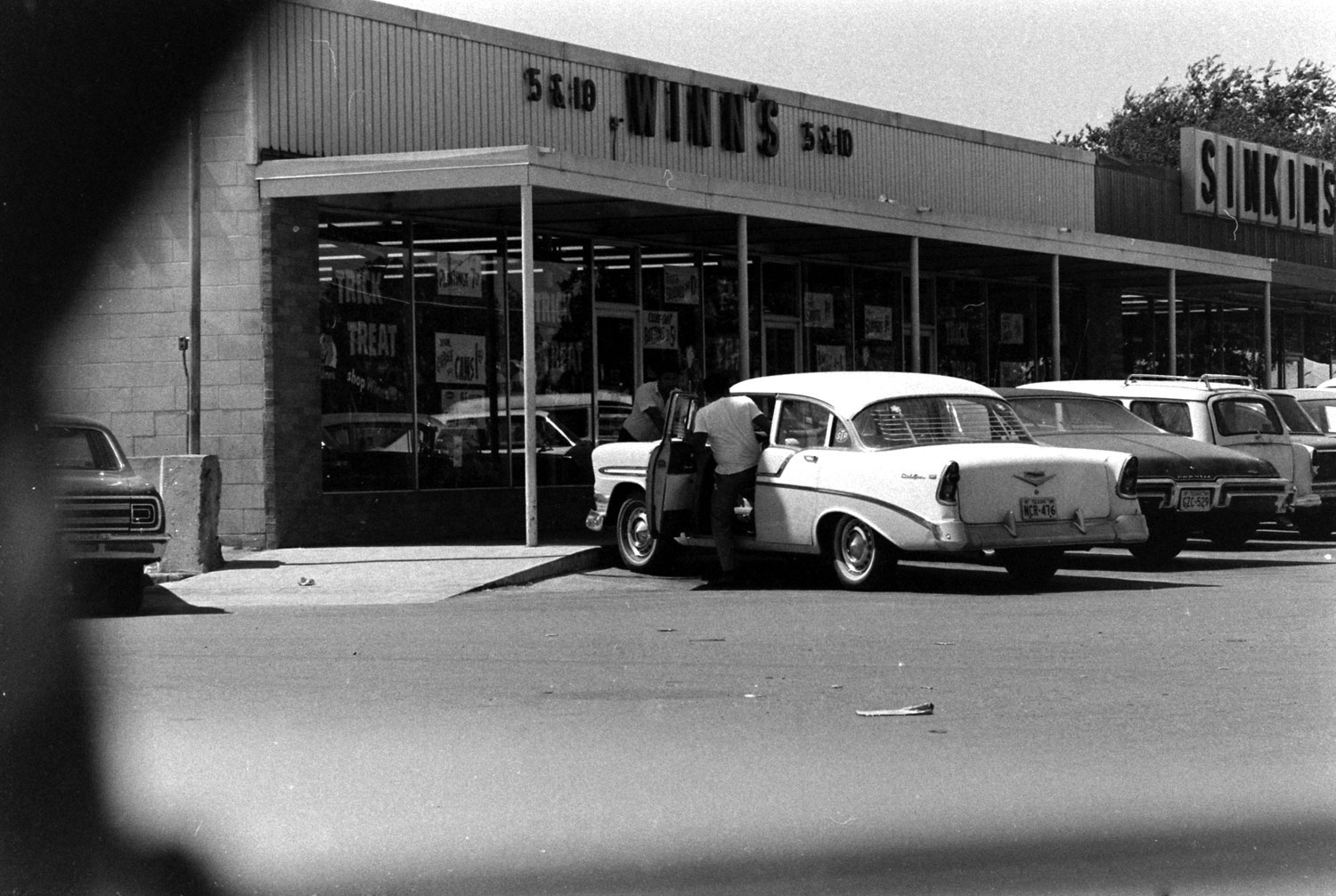

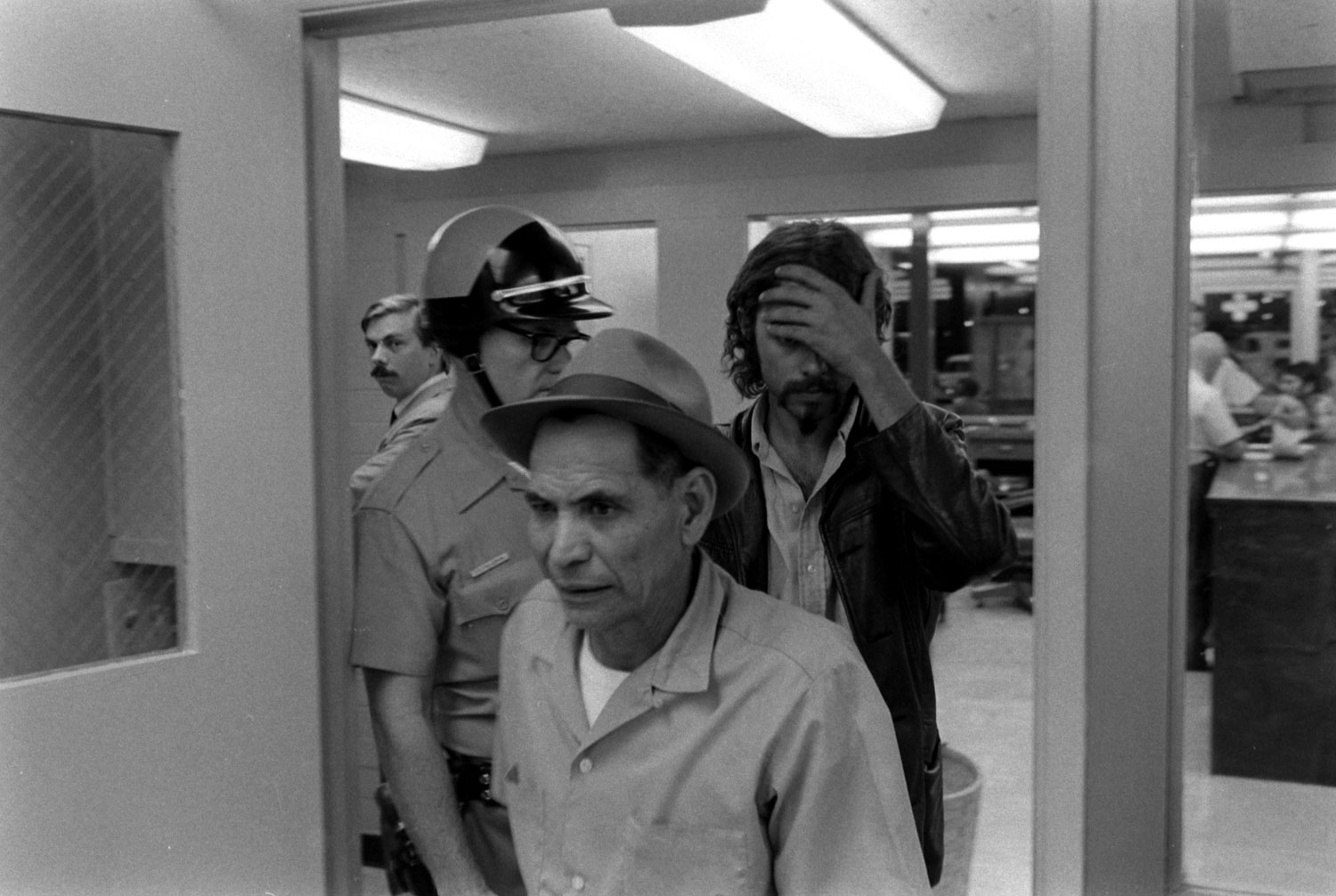

The souring of relations between the U.S. and Mexico over the drug trade began in the 1960s. Americans have long traveled to Mexico seeking illicit thrills of all types (it was a favorite destination for the Beat writers of the 1950s, as well as William Burroughs’s choice of relocation after facing drug and weapons charges in the U.S.), but for many years the burden fell on the Mexicans to keep drug-taking vagabonds from the States out of their country. A March 30, 1969 Los Angeles Times article featured a group of teenagers from California who had been thrown in jail for marijuana possession, pointing out that “Mexican authorities are dealing harshly with hippies, or those who look like U.S. hippies. Since the beginning of the year more than 100 have been deported, many with their heads and beards shaved and their cars confiscated.” American officials were more than happy to accept these deportations and Mexico was generally commended for its attempts to crack down on narcotics trafficking, which was relatively small-scale compared to today’s operations.

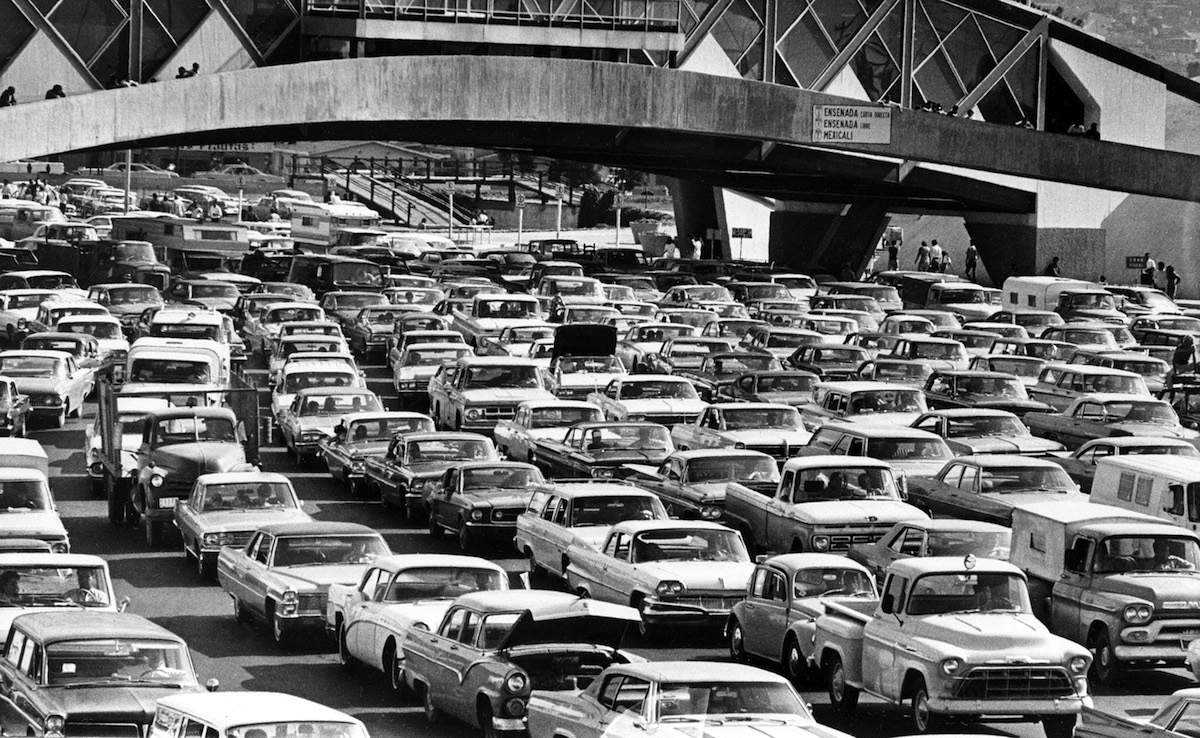

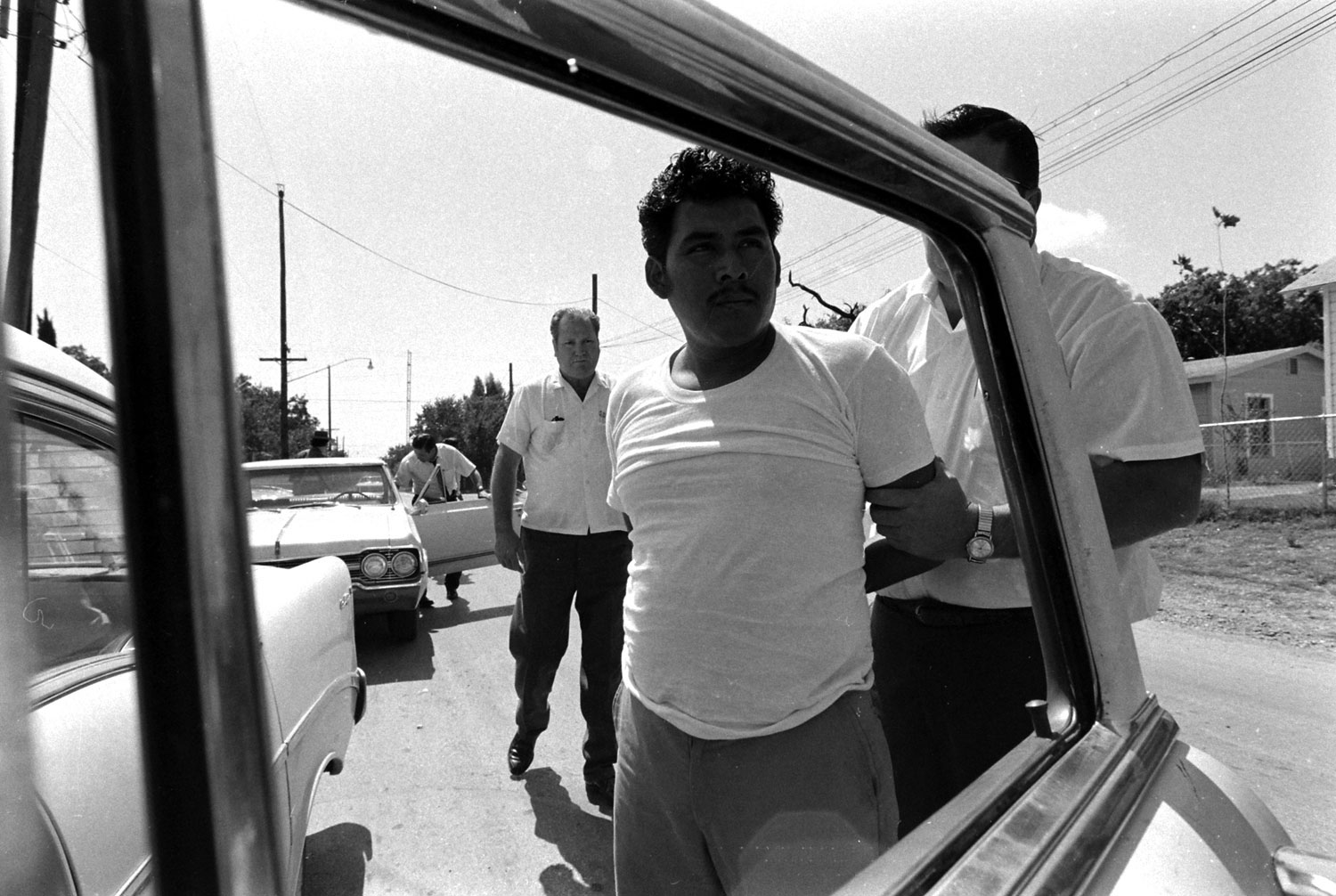

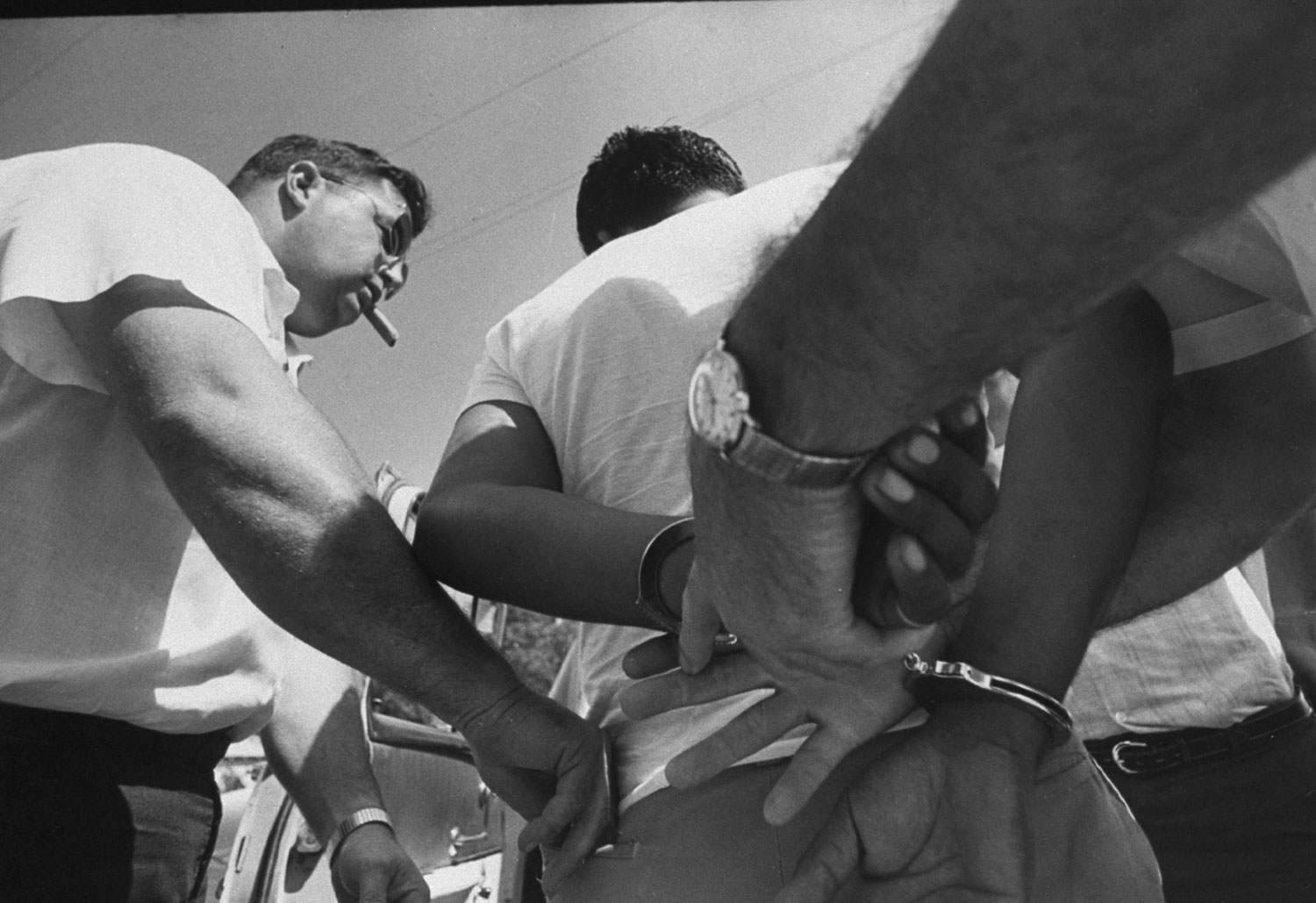

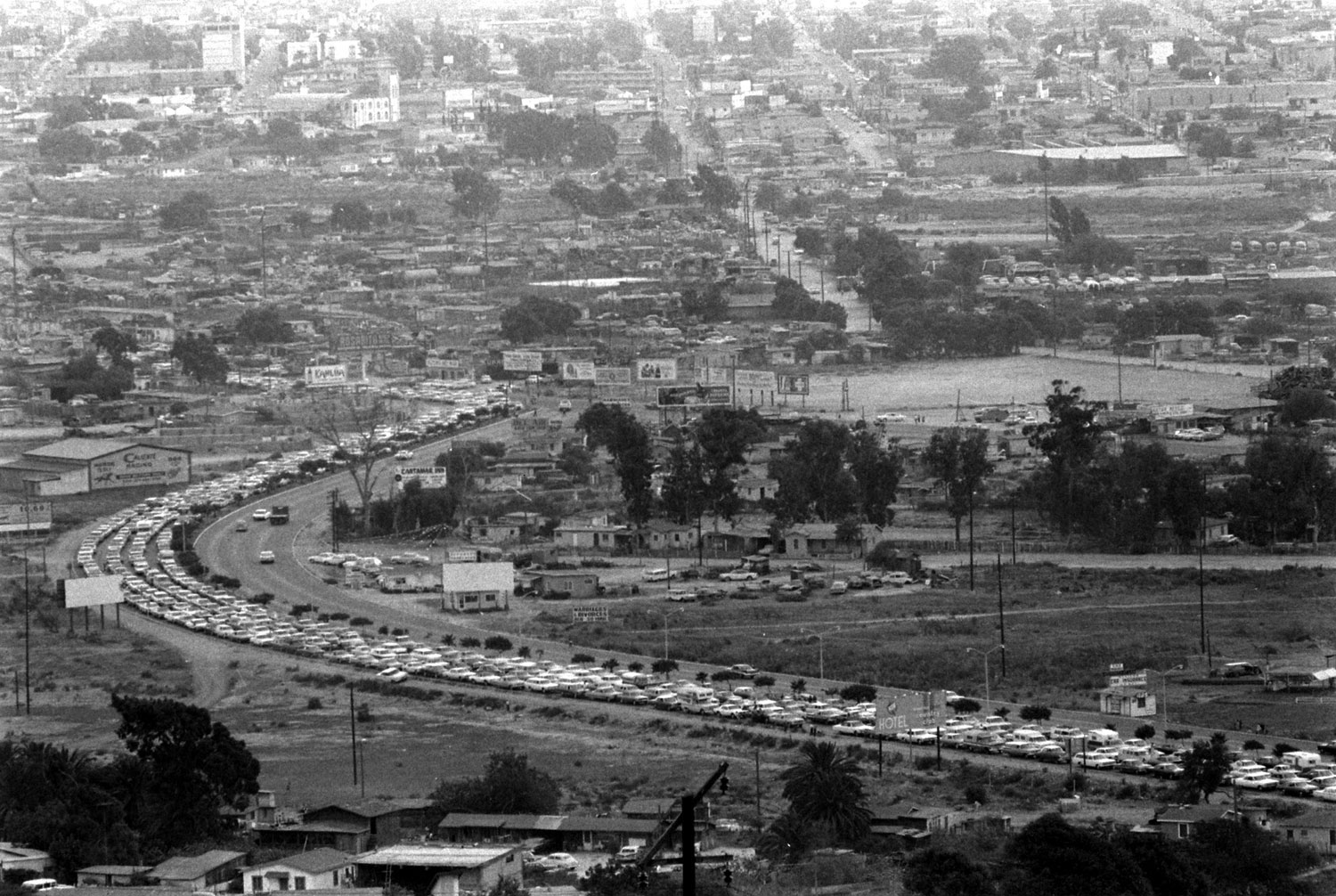

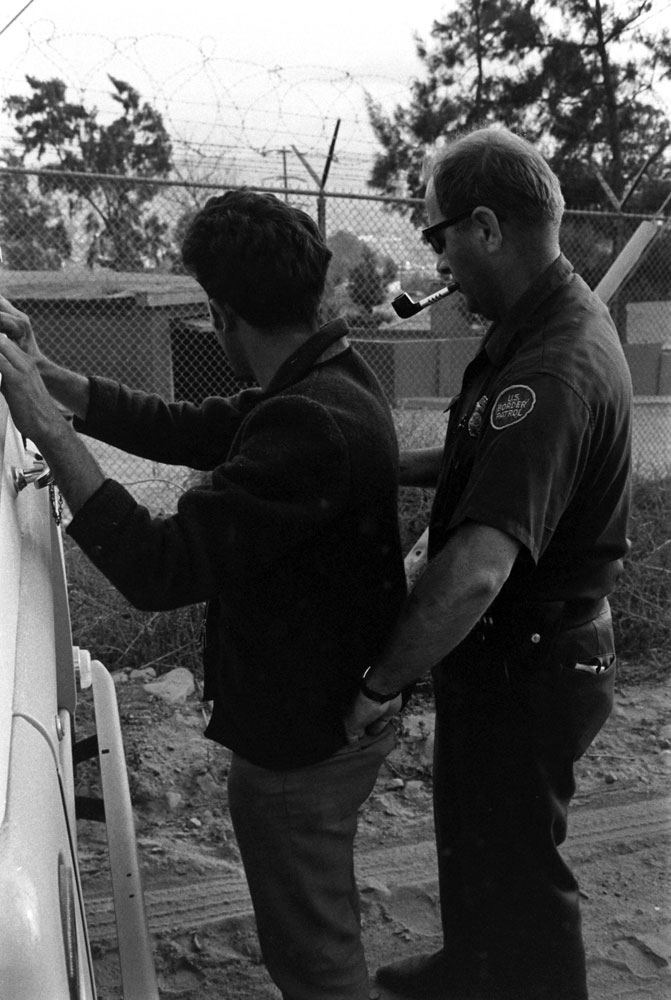

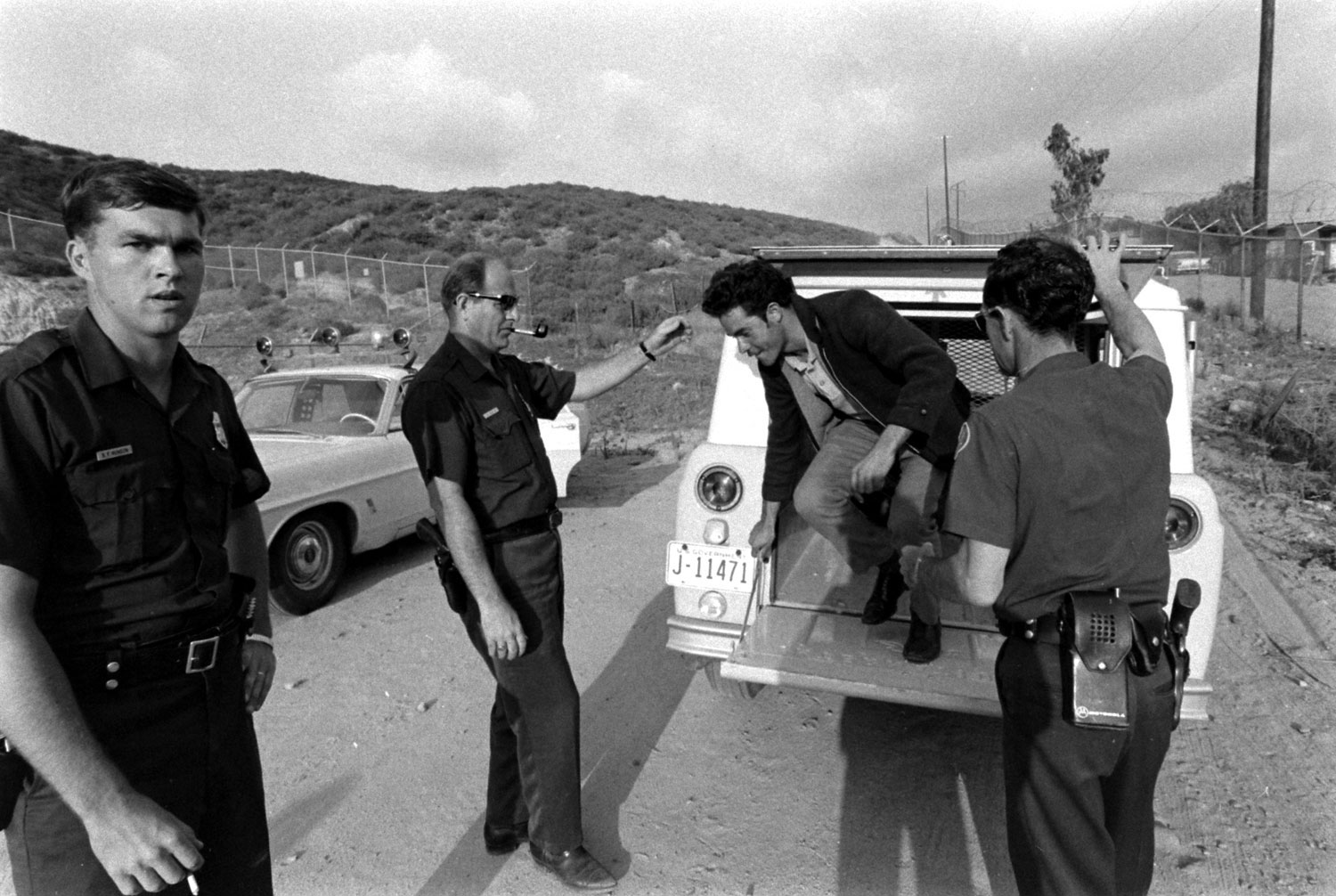

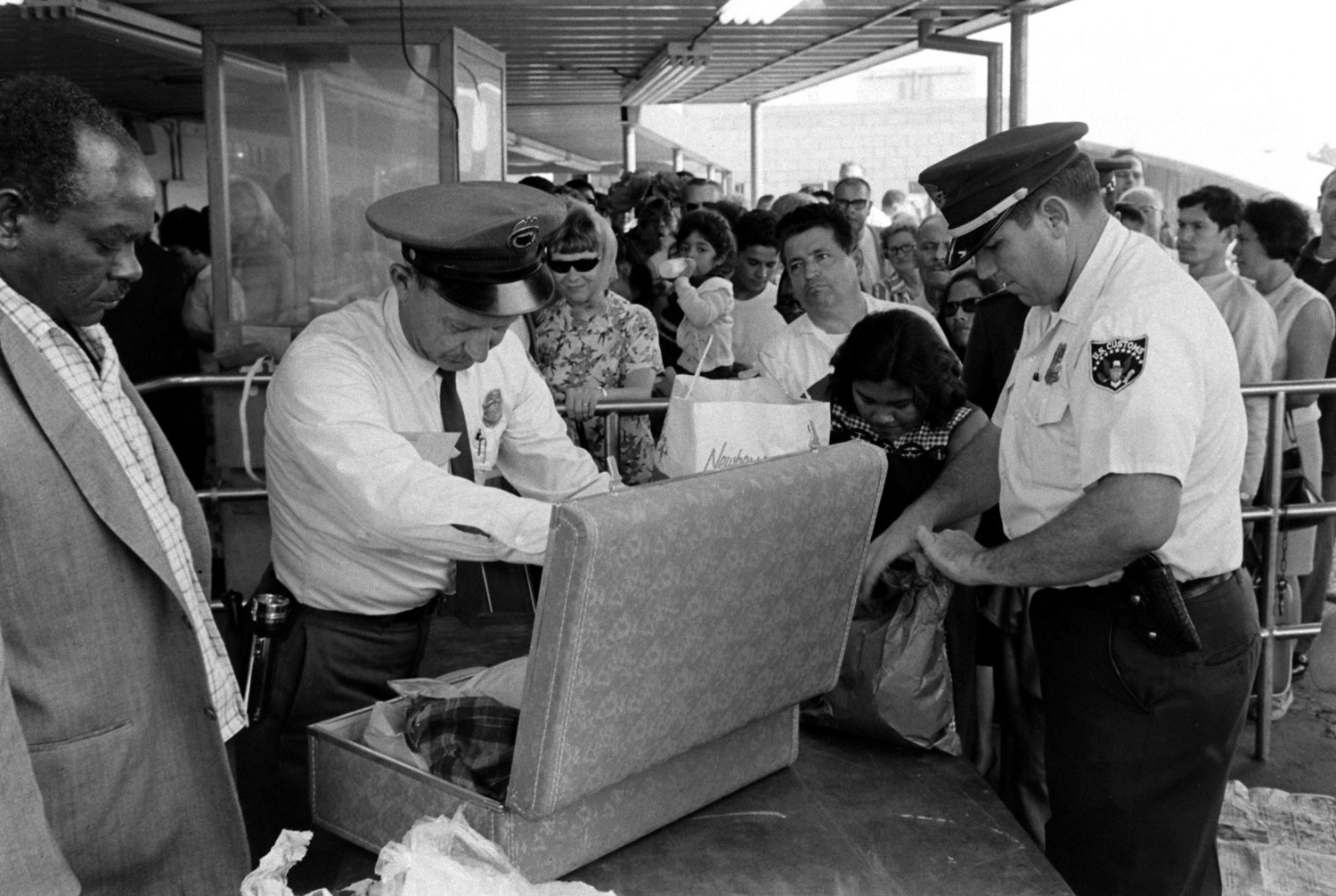

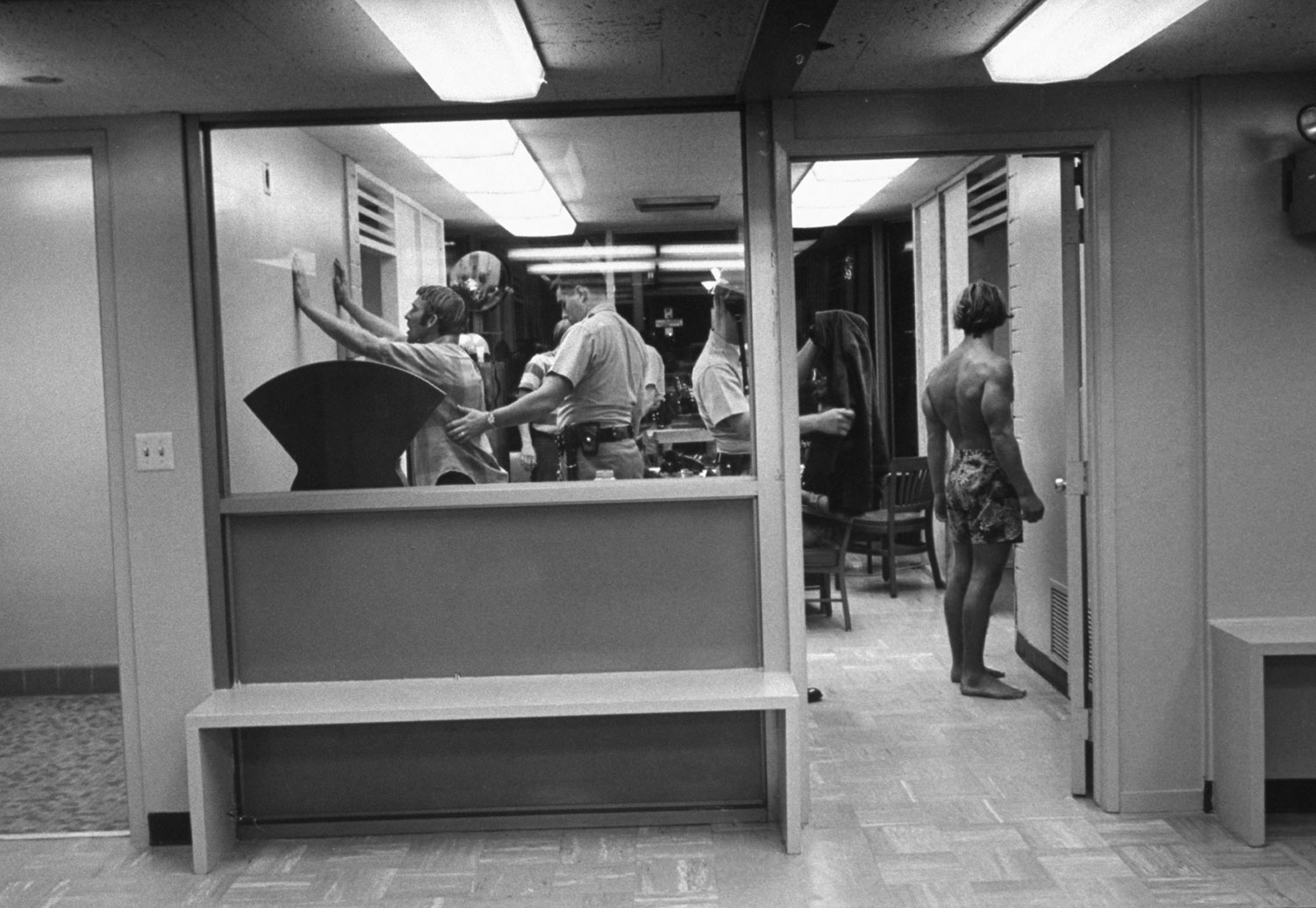

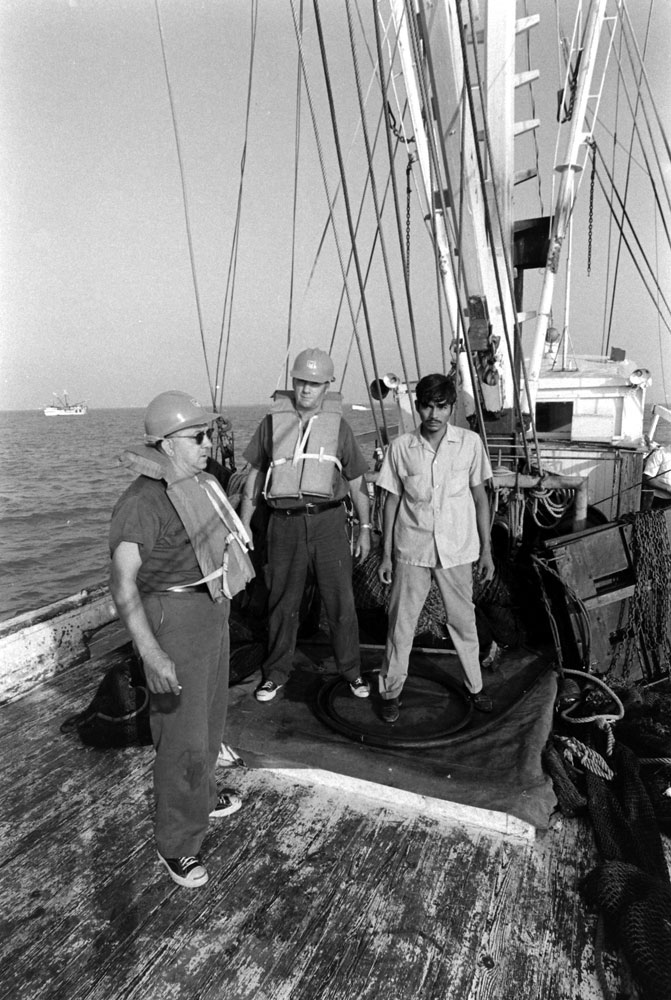

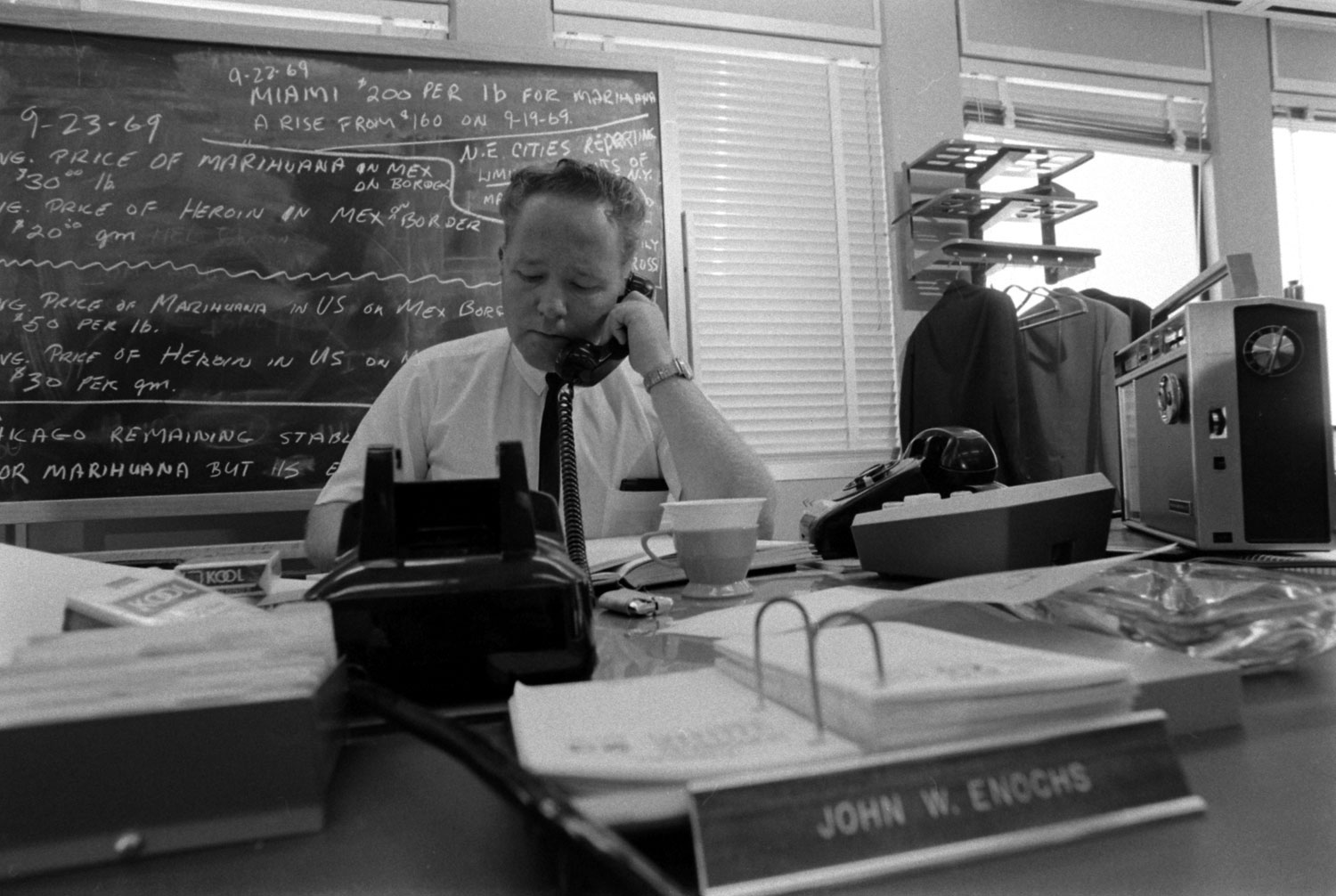

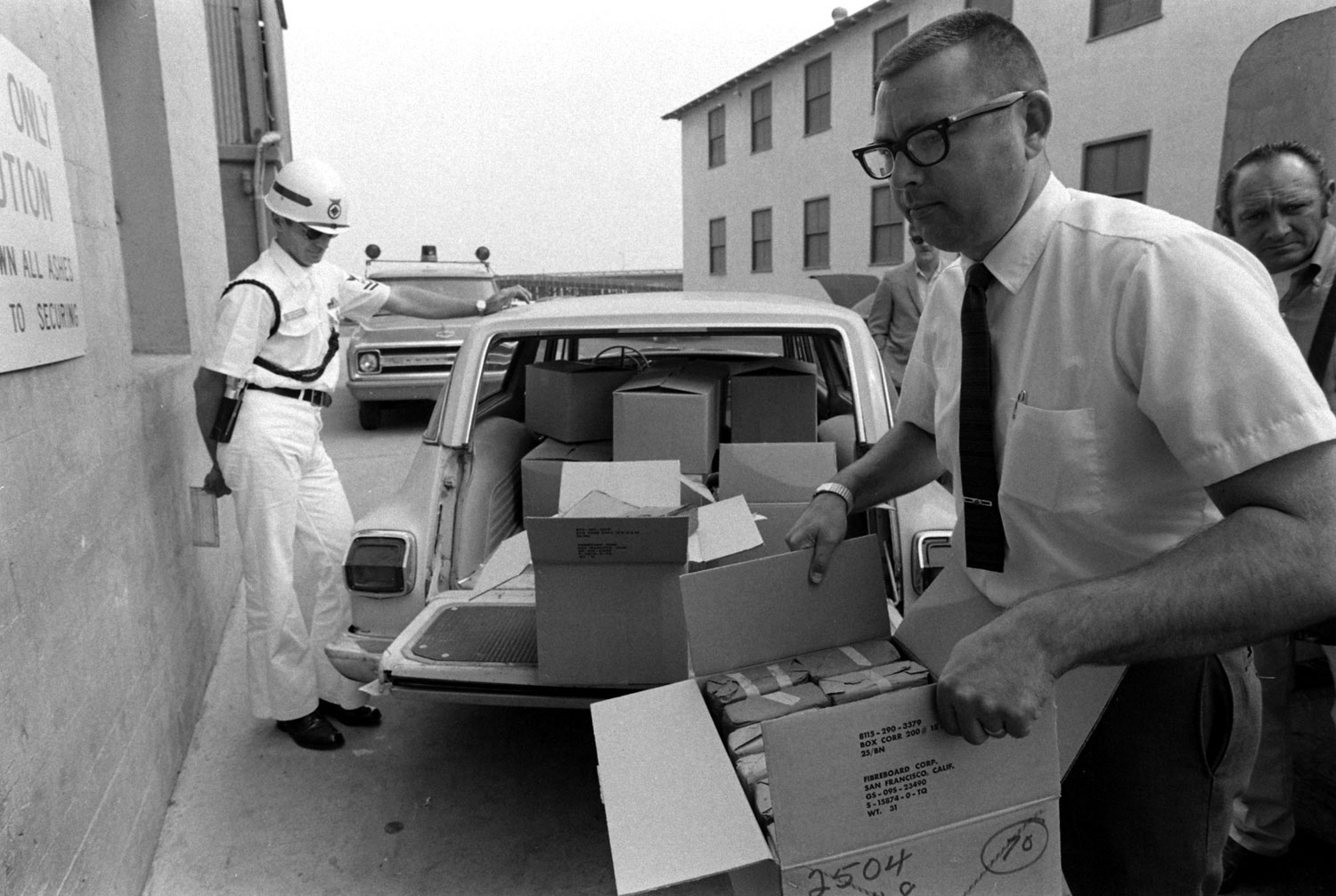

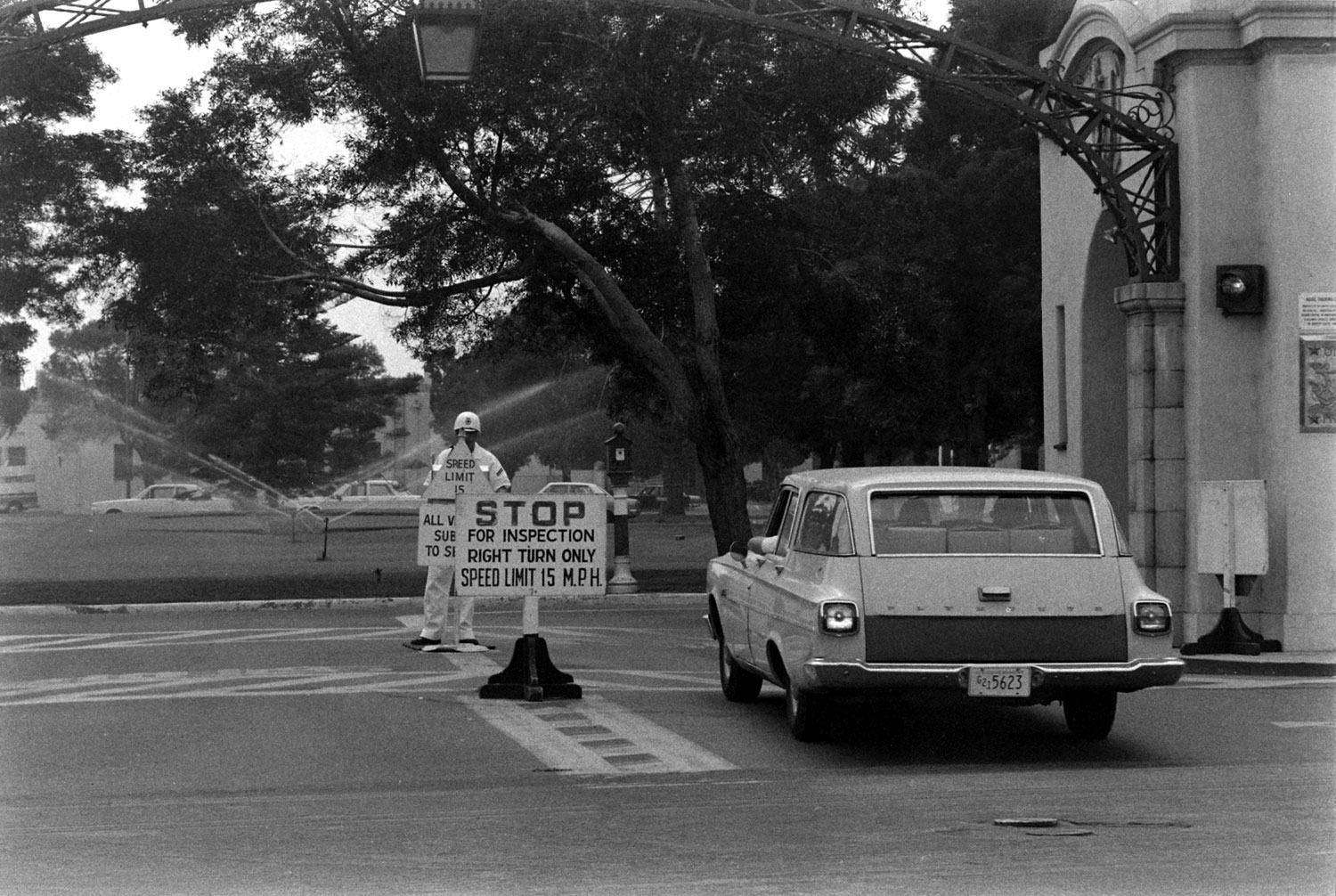

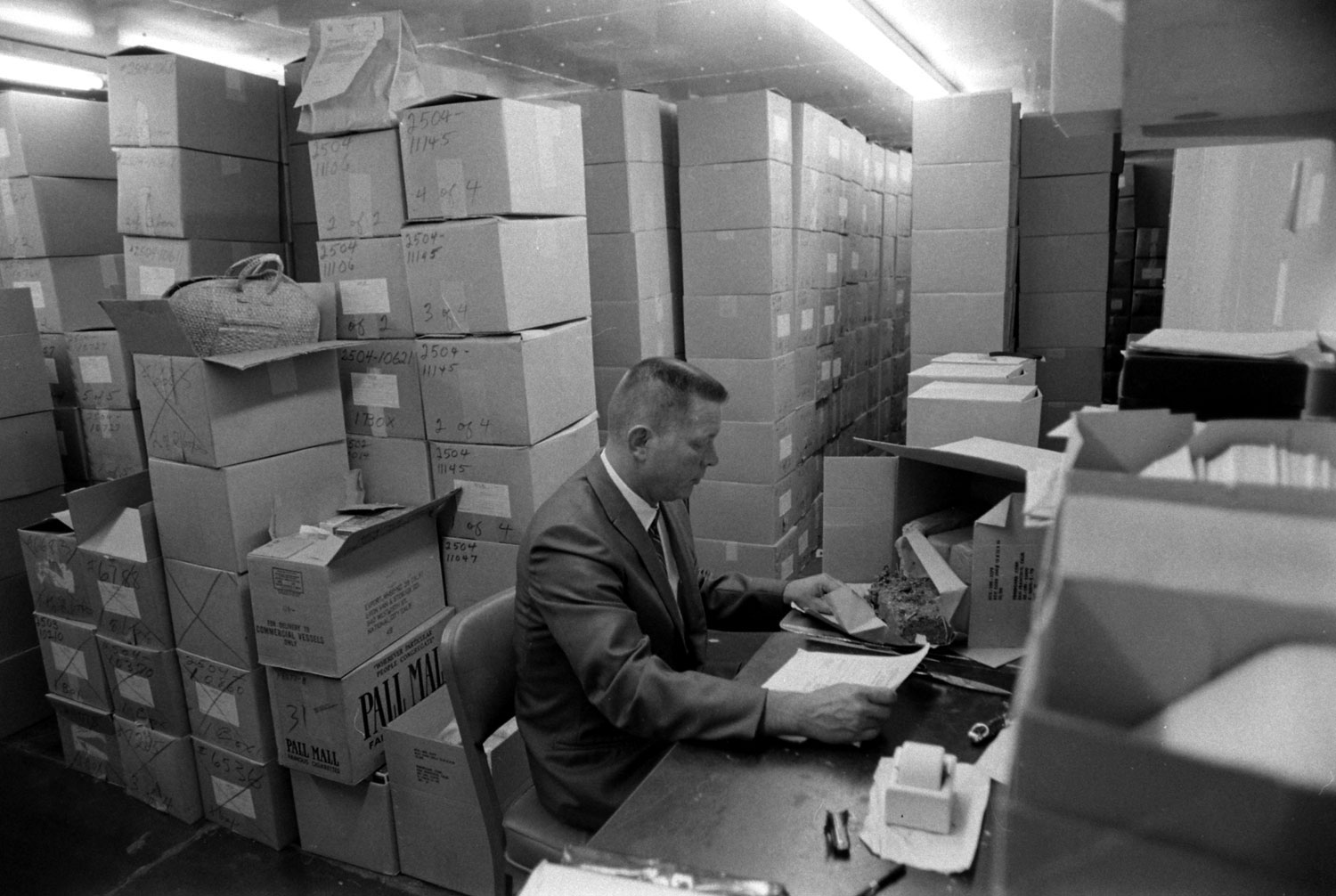

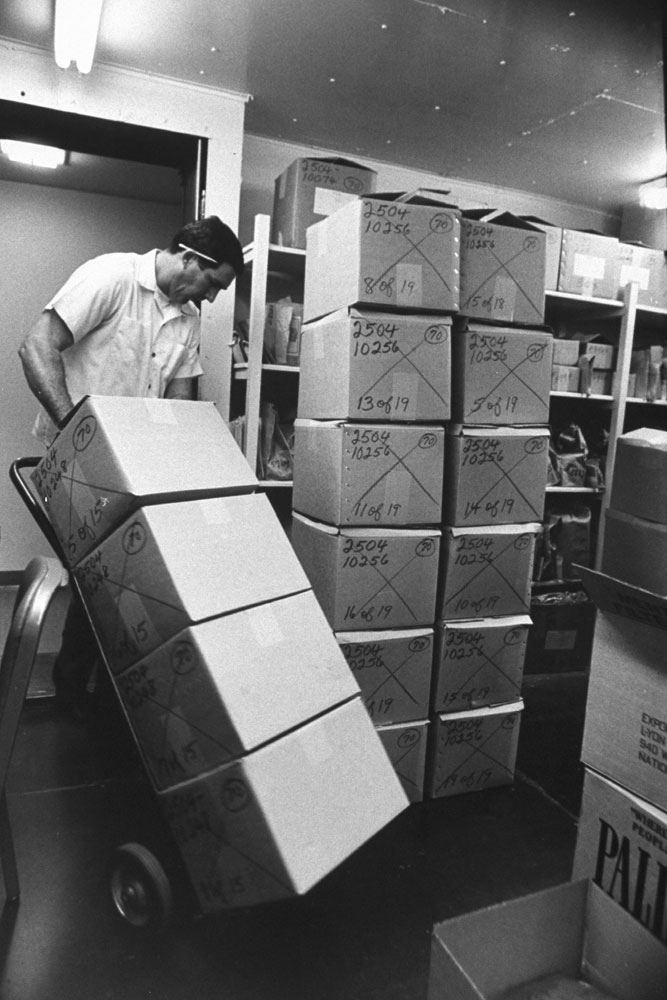

But Richard Nixon, who won the presidency in 1968 largely on a platform of law-and-order, was unhappy with Mexico’s progress in stamping out the drug trade and decided that the U.S. should put relentless pressure on its southern neighbor to eliminate both traffickers and drug crops. Nixon urged Mexican president Gustavo Díaz Ordaz in September 1969 to step up drug eradication efforts, to which the Mexican leader replied that it was the Americans who were using most of the drugs and exporting firearms to his country. Nixon agreed to “look into this matter,” but the conversations between Washington and Mexico City have more or less mirrored this exchange ever since. When Nixon implemented Operation Intercept shortly after his meeting with Díaz Ordaz, effectively shutting down car and foot traffic between the U.S. and Mexico for days in the largest peacetime search and seizure effort to date, it was his way of sending a message to Mexico City that the U.S. would no longer play by the old rules. Operation Intercept jump started the war on drugs as we know it today – a combination of police work, counterinsurgency tactics, and efforts to eliminate marijuana, opium, and coca at their source – and it has since created major headaches for both the U.S. and Mexico.

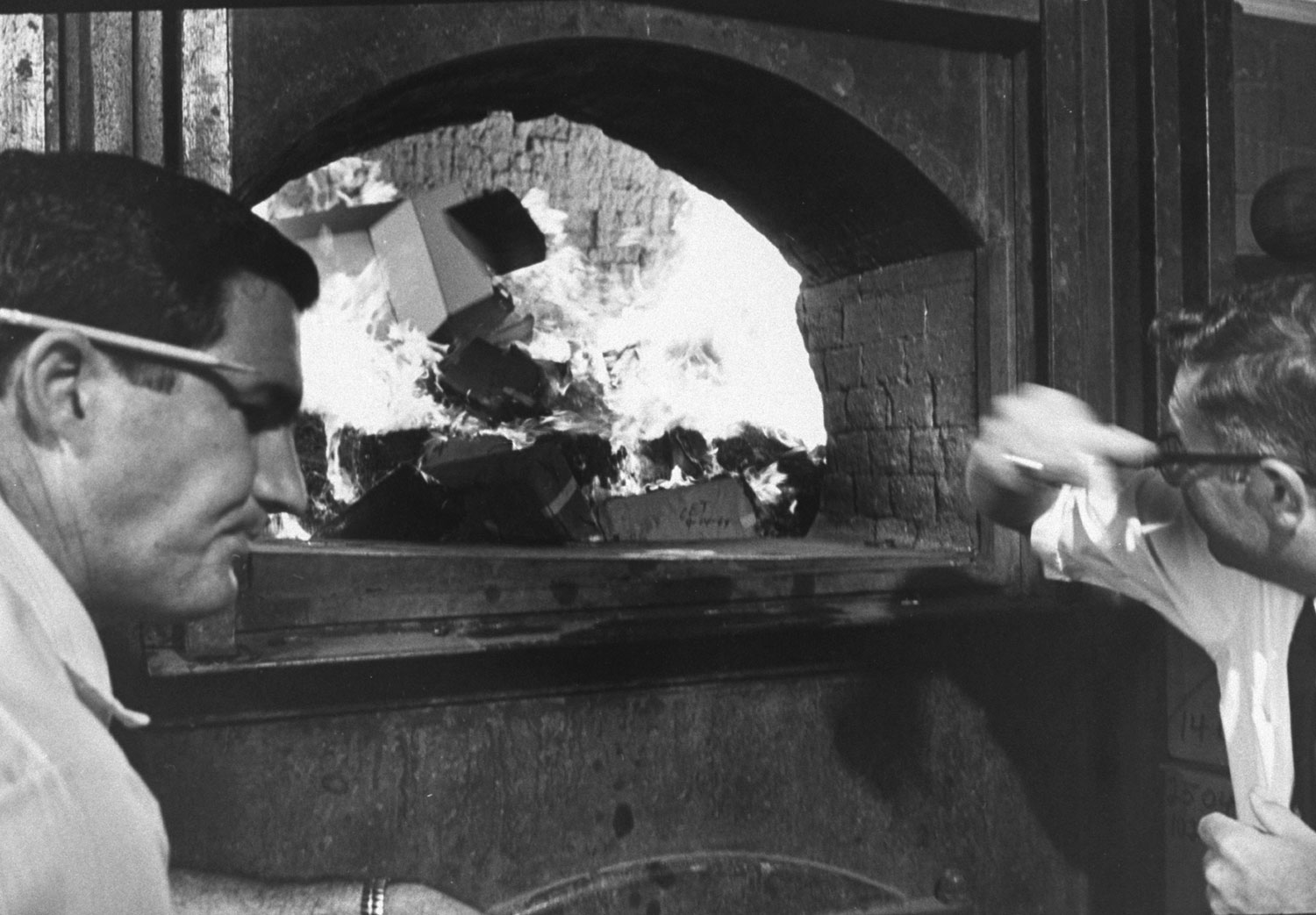

What America's War on Drugs Looked Like in 1969

As marijuana and heroin use increased in the U.S. during the 1970s, the earliest incarnations of the Mexican cartels that are battling for control of the country’s illicit trade routes today began to emerge. And as the U.S. and Colombia gained headway in dismantling the Medellín cartel in the 1980s, the Mexican traffickers took over the lucrative cocaine market. Once the drug dollars began pouring in, corruption reached unprecedented levels and began to penetrate all levels of Mexican society. Violence increased exponentially and began to affect Americans directly. Perhaps the most chilling event occurred in 1985, when Mexican-American DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena was brutally tortured and murdered by a drug gang in the state of Michoacán. These developments set off alarm bells in Washington, prompting members of the House Foreign Affairs committee to declare in 1986 that Mexico was “probably the most corrupt nation on earth” and “a problem area of immense proportions.” By 1988, Democrats were battling Republicans to “seize the initiative” on combatting drug trafficking and violence south of the border.

Mexico’s drug cartels have acquired even more power and control over large parts of the country since the 1980s, and the U.S. still views its southern neighbor with suspicion. Presidential candidate Donald Trump’s recent promise to build a “big beautiful wall” to keep out Mexican “rapists” and “criminals” is an attempt to exploit existing fears about threats emanating from Mexico. While such xenophobic rhetoric is certainly counterproductive and divisive, it is just the latest example of how the inability of the U.S. and Mexico to solve the problem of drug trafficking has led to further distrust between the two countries. Mexico might agree to extradite El Chapo to the United States this time, but Americans will continue to abuse narcotics and guns will continue to flow south. Until the two countries can come to a mutual agreement where real concessions are made on these fronts and Mexico no longer sees itself as a scapegoat for American problems, the violence will continue and another El Chapo will emerge to fill his shoes.

Aaron Brown is a PhD student studying US history and foreign relations at Ohio University. He is also a fellow at the university’s Contemporary History Institute and has written for the History News Network, American Diplomacy, and The Athens (Ohio) News.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com