Singers, attuned to expressing themselves in ways that go beyond words, often make wonderful actors, and David Bowie—who died on Sunday at age 69—was a supreme example. You could even argue that the key to Bowie’s charisma as a singer is proved, not so paradoxically, in his acting. The ambling angularity of his gait, the delicate trigonometry of his slender hands, the way his eyes held the camera lens as if it were a compass needle and they were true north: In his film performances, Bowie’s face, his body and his demeanor were like science and music mingled. You couldn’t tell, and wouldn’t want to parse, where one left off and the other began.

Even in small roles, Bowie was always magnetic. In David Lynch’s underappreciated but chillingly hypnotic Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992), he played an FBI agent, Phillip Jeffries, who returns to headquarters in Philadelphia after being missing for two years. Bowie’s Jeffries emerges from an elevator in a pale, floppy, decidedly un-FBI-like suit and strides into the office of the regional bureau chief (played by Lynch) and proceeds to hurl accusations at Kyle MacLachlan’s Agent Dale Cooper. His words, rendered in a rubbery Southern accent, come out as authoritative-sounding gibberish. We can hear that he’s gone mad, but we also see it in his body language: He walks like a bow-legged sailor, his limbs as unhinged as his mind.

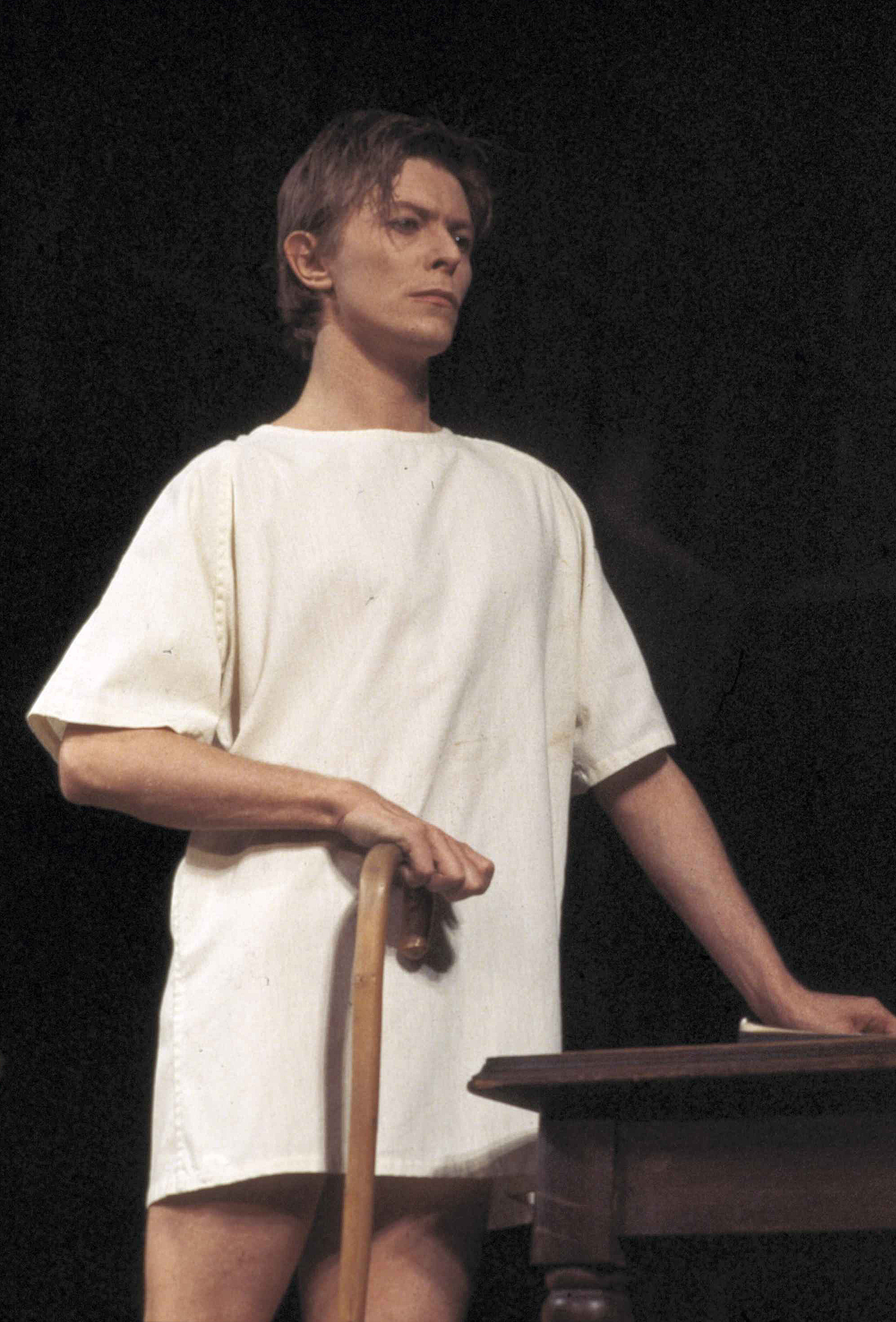

But if we’re talking about sheer physical beauty, the 1980s were Bowie’s golden years—provided you can bring yourself to choose a favorite decade when it comes to this most beautiful of men. In Nagisa Oshima’s Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence (1983), he played a guilt-ridden Army major imprisoned in a Japanese POW camp: With his smooth sweep of dyed-blond hair and direct, blue-eyed gaze, he was the ’80s heir to Peter O’Toole, though his allure carried more menace than O’Toole’s did. Bowie often had the intensity of a lizard assaying a stranger. There could be a touchingly honest wariness about him, which must have made him perfect for the physically demanding role of David Merrick in Bernard Pomerance’s play The Elephant Man, which he performed on Broadway in late 1980 and early 1981 (a performance I never saw and dearly wish I had).

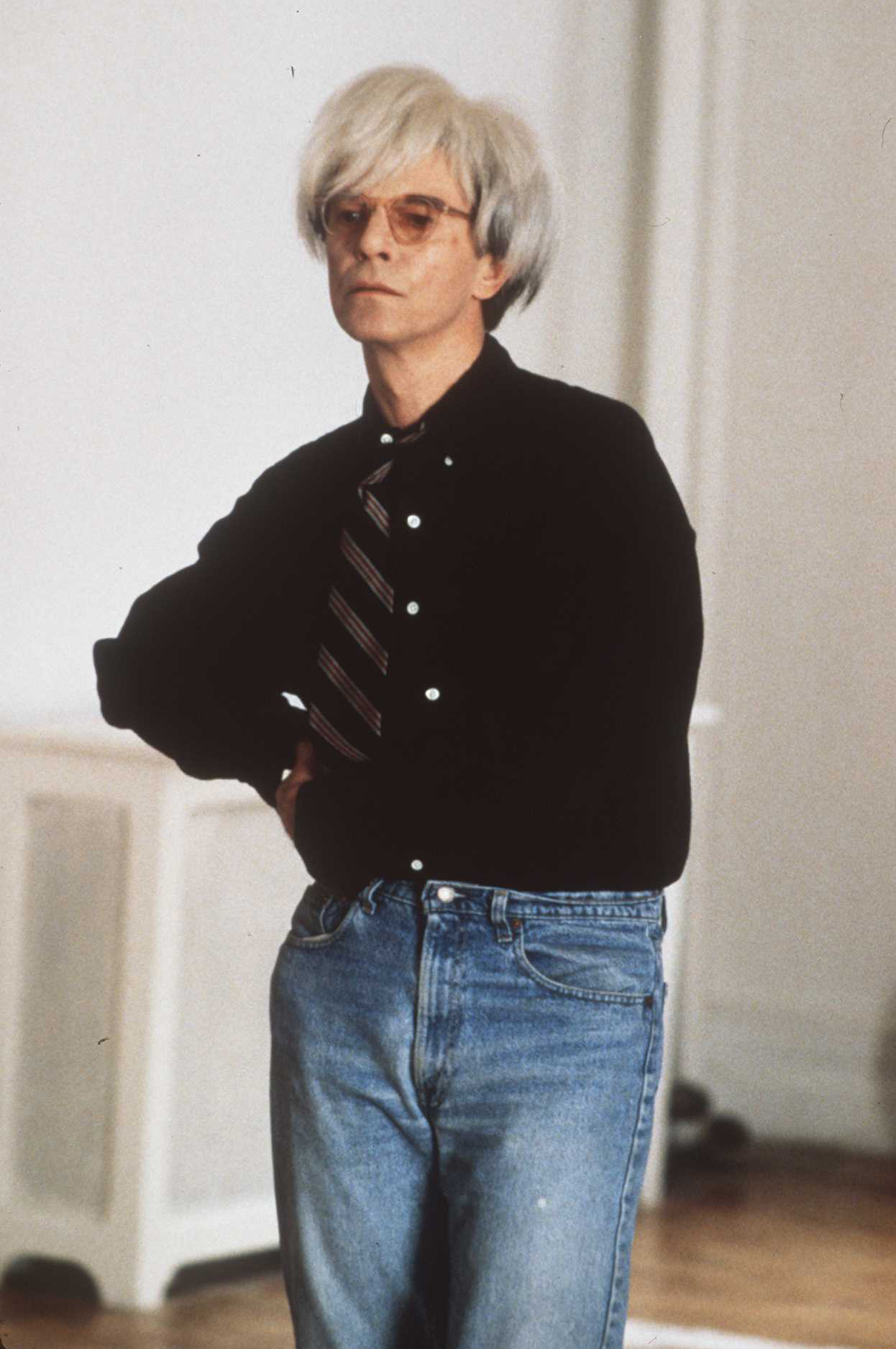

Bowie often played villains, or semi-villains, but even then, his portrayals were always intensely seductive, and usually at least a tad sympathetic. In Jim Henson’s 1986 fantasy-adventure Labyrinth, he made a sexy and ridiculous Goblin King, done up in a Rod Stewart rooster cut and a black cape with a broad collar like a crow’s wingspan. He brought just the right degree of intimidation, and a sense of humor, to the role. And in Martin Scorsese’s 1988 The Last Temptation of Christ, he made an unnervingly erotic Pontius Pilate. His purring interrogation of Willem Dafoe’s Jesus is both electrically calm and deeply unsettling. He turned this classically Biblical baddie into the most complex sort of villain: one who comes off as reasonable.

Of Bowie’s more than 30 film performances, two in particular stand out for their grace and intensity. In Tony Scott’s 1983 vampire thriller The Hunger, Bowie played John Blaylock, one-half of a supposedly happy, longtime vampire couple. But his mate, Catherine Deneuve’s Miriam, appears to be losing interest in him. And, as it turns out, she has betrayed him: A few centuries back, when she turned him into a vampire, she promised him immortal life—just not immortal youth. In one potent scene, he examines his eyelids in a magnifying mirror, noting their invading crepeyness. And after the couple have made a kill, they take a languorous, sexy shower together, the better to wash off the blood. Bowie’s John asks Miriam, with just a hint of pleading in his voice, “Forever?” When she responds with an absent-minded “What?” he asks her again, “Forever and ever?” though it’s clear he knows that their mutual forever has ended. Afterward, he lies in bed, unable to sleep. He smokes a cigarette in front of a window, bathed in dusky blue light. His face is that of a man who feels mortality closing in and youthful glamor draining away. But beneath it all, you know what he’s really mourning—in the depths of his strange blue eyes, so openly intimate and faraway at once—is the loss of love.

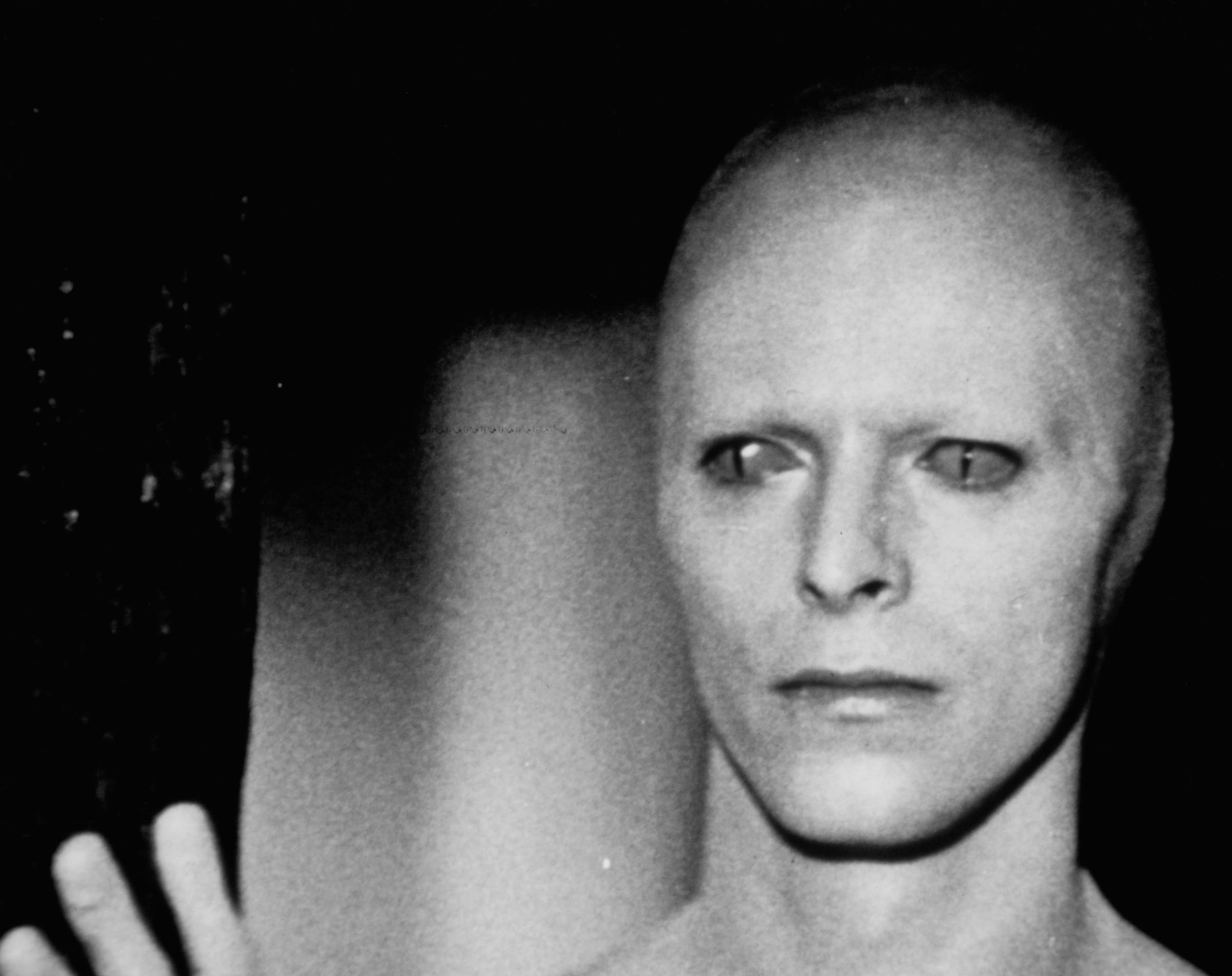

You could call Bowie’s role in The Hunger something of a bookend to the one he played in his acting breakthrough, in Nicolas Roeg’s luminous 1976 science-fiction reverie The Man Who Fell to Earth. As Thomas Jerome Newton, an alien who has come to Earth disguised as a human being, desperate to save his waterless home planet, Bowie radiates an otherworldly coolness—it seems to pour off his body the way we humans, made of regular flesh and blood, give off heat. His scenes with Candy Clark as Mary-Lou, the human woman he almost loves, are deeply touching in their urgency. He’s chilly toward her, even cruel—but the distance he puts between himself and her is also a kind of protection, for both his sake and hers. He knows she can’t accept him as he really is. He also can’t shake off his past life— he longs for it with a piercing single-mindedness.

It’s in this performance that Bowie’s magnificent eyes—one with a pupil perpetually dilated, caused when a childhood friend landed a punch that hit terribly right—cast their biggest spell. They’re haunting in the number of secrets they reveal, but also in what they hold close. His Thomas is a man who’s not a man at all. Yet by being forced to play one in his strange new landscape, he inches closer to knowing what it means to be human—and the more we watch him, the less alien he seems to us as well. At one point Rip Torn, as the scientist who befriends Thomas (and who believes he’s from England and not some faraway planet), quotes the Royal Air Force motto: Per ardua ad astra, which translates into “Through difficulties, to the stars.” It could be a motto for all of us, but stars, as we know from so much of Bowie’s music, held special power for him. The difficulties are over. He’s on his way now.

From Stage to Screen: See David Bowie’s Best Acting Roles

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com