The recently declassified top-secret U.S. military document that was published on Tuesday by the National Security Archive at the George Washington University is shocking for a number of reasons. Written in 1956, the Cold War-era report, titled the Strategic Air Command (SAC) “Atomic Weapons Requirements Study for 1959,” contains a list of targets that would be priorities in the case of atomic war with the Soviet Union and its allies.

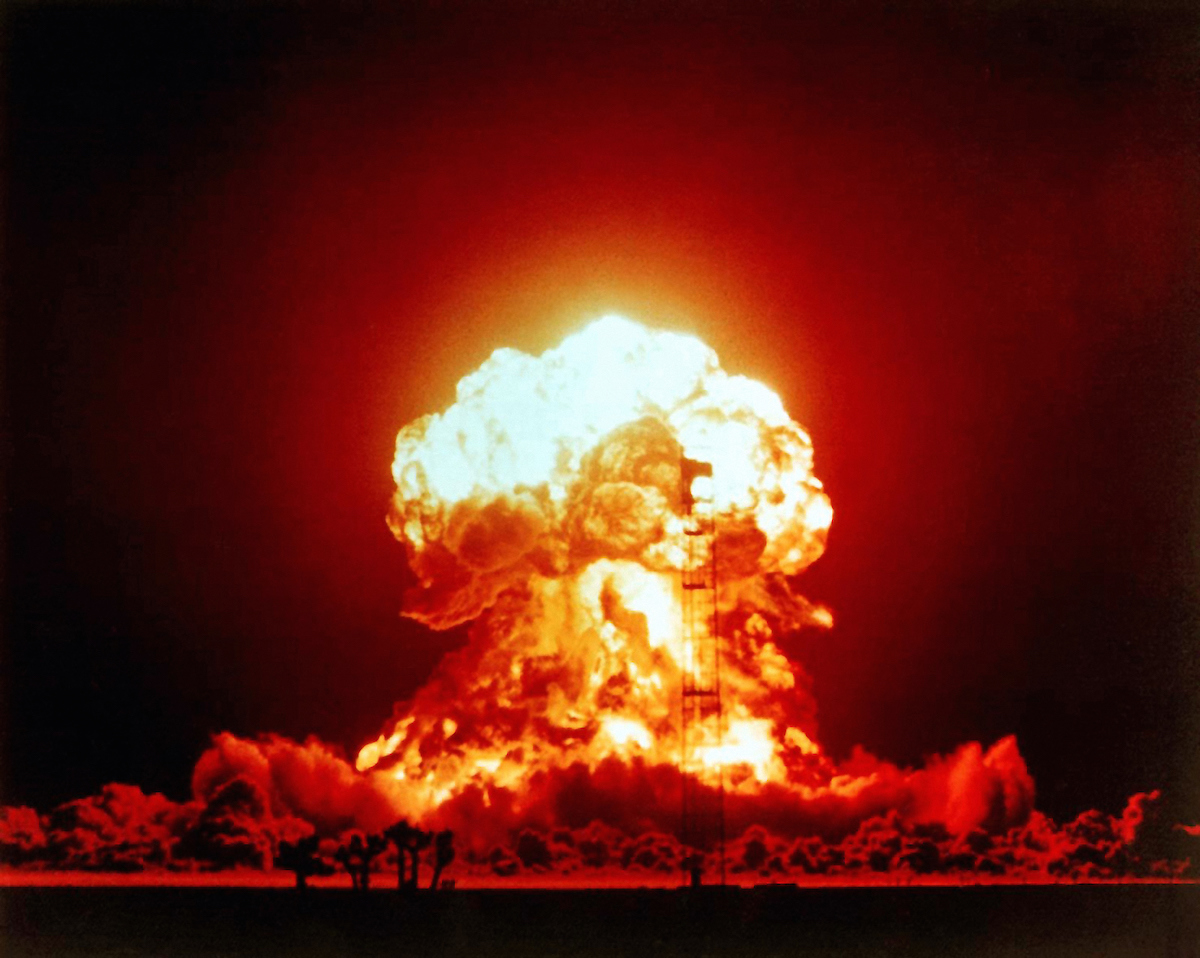

As analyst William Burr points out in his extremely thorough explanation of the document’s context and significance, the list of airfields and industrial targets also included urban centers, indicating that “people as such, not specific industrial activities, were to be destroyed” in the event the plan was carried out. Given today’s knowledge of the long-term effects of atomic explosions, it’s clear that the plan so dryly laid out by U.S. intelligence would have resulted in death and destruction unlike anything the world had or has ever seen.

But lurking behind the frigid calculus of Cold War nuclear strategy is a bit of context that the report’s authors might already have suspected in 1956: by the time the plan would have been put into effect in 1959, it would already have been pretty much obsolete.

As Burr explains, the priority targets listed in the plan are those connected to Soviet air power, because the age of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) had not yet arrived. In other words, the U.S. would use its own bombers to target Russian airfields because the only way to drop a nuclear weapon at the time was to ferry it to its target via plane.

But even as the report was being drafted, it was public knowledge that this technological limitation was changing. In fact, TIME devoted a January 1956 cover story to the impending arrival of the missile on the Cold War scene. Though official announcements remained “brief and vague” it was known that such missiles were the “No. 1 crash program of the U.S. armed services.”

Long-range guided missiles with nuclear capabilities weren’t a new idea. Germany had used primitive versions of non-nuclear missiles in World War II, and the advantage of combining missiles with atomic power was obvious after 1945. It had taken a decade, however, for computer and rocket technology to get to the point where such missiles were a near-term possibility. Another necessary development was the shrinking of nuclear weaponry. At a lighter weight, atomic bombs could be carried by lighter missiles propelled to higher speeds by lighter motors. That breakthrough “changed all the equations of scientific war,” TIME noted, “and it forced on the Department of Defense a grave decision: to concentrate intensively on the ICBM.”

So why was the Strategic Air Command spending its time coming up with a plan for a 1959 attack that assumed a world without ICBMs? As TIME explained, the military was simply covering all its bases:

Will the ICBMs work, and when will they be ready? Most missile experts seem to believe that the task of developing them is not impossible, but that the timetable is uncertain. It may be five or even ten years, say the pessimists. Meanwhile, the U.S. must keep itself able to ward off more conventional attacks on its territory, and also be able to retaliate if an attack comes. Even high Air Force officers who have most faith in the ICBM feel that the U.S. must push conventional programs, both offensive and defensive, almost as if the ICBM were impossible.

General Curtis LeMay, head of the Strategic Air Command, is emphatic on this point. He is not against missiles, though sometimes quoted as being so, but he feels that in air warfare it is always necessary to keep one’s eye on the ball, not on the distant future. “We must put more time and money,” he says, “into the development of these birds. Missiles are another step in the evolution of war. We will use them as we get them, and we will get them when they are effective and reliable.” LeMay’s mission is to be ready for instant, effective action. He wants a continuous supply of weapons that will make such action possible, including lesser missiles than the ICBM.

The development of ICBMs was especially important, not just because it would change the priorities for an imaginary nuclear war but also because it removed an attacker’s advantage. As TIME put it in July of 1956, the year the now-declassified plan was written, the “fear of atomic war stems from the fact that the aggressor still has an outside chance to profit from attack. The ICBM will end all hope for such aggression, however devastating, without sure and deadly retaliation.”

With the advent of assured second-strike capability, the entire nuclear military calculus would change, rendering all non-ICBM plans for future strategy—like the document just released—fairly useless.

By April 1957, TIME devoted another cover story to the topic of missiles. Much had changed in the intervening year. “In the Convair plant at San Diego one day last December,” the story began, “a mysterious piece of hardware was carefully cantilevered down from a vertical position inside a closely guarded seven-story shed. Draped in a white canvas shroud, lashed to a yellow, tubular steel trailer, the top-secret cargo was hauled out onto U.S. Highway 80 to begin a 2,500-mile trip across the southern U.S. … Under the shroud was Atlas, the U.S. intercontinental ballistic missile.”

By 1959, Atlas missiles were ready to use. The age of the nuclear bomber was over, and the age of the ICBM had begun.

Read the full 1956 cover story about missiles, here in the TIME Vault: The Missile

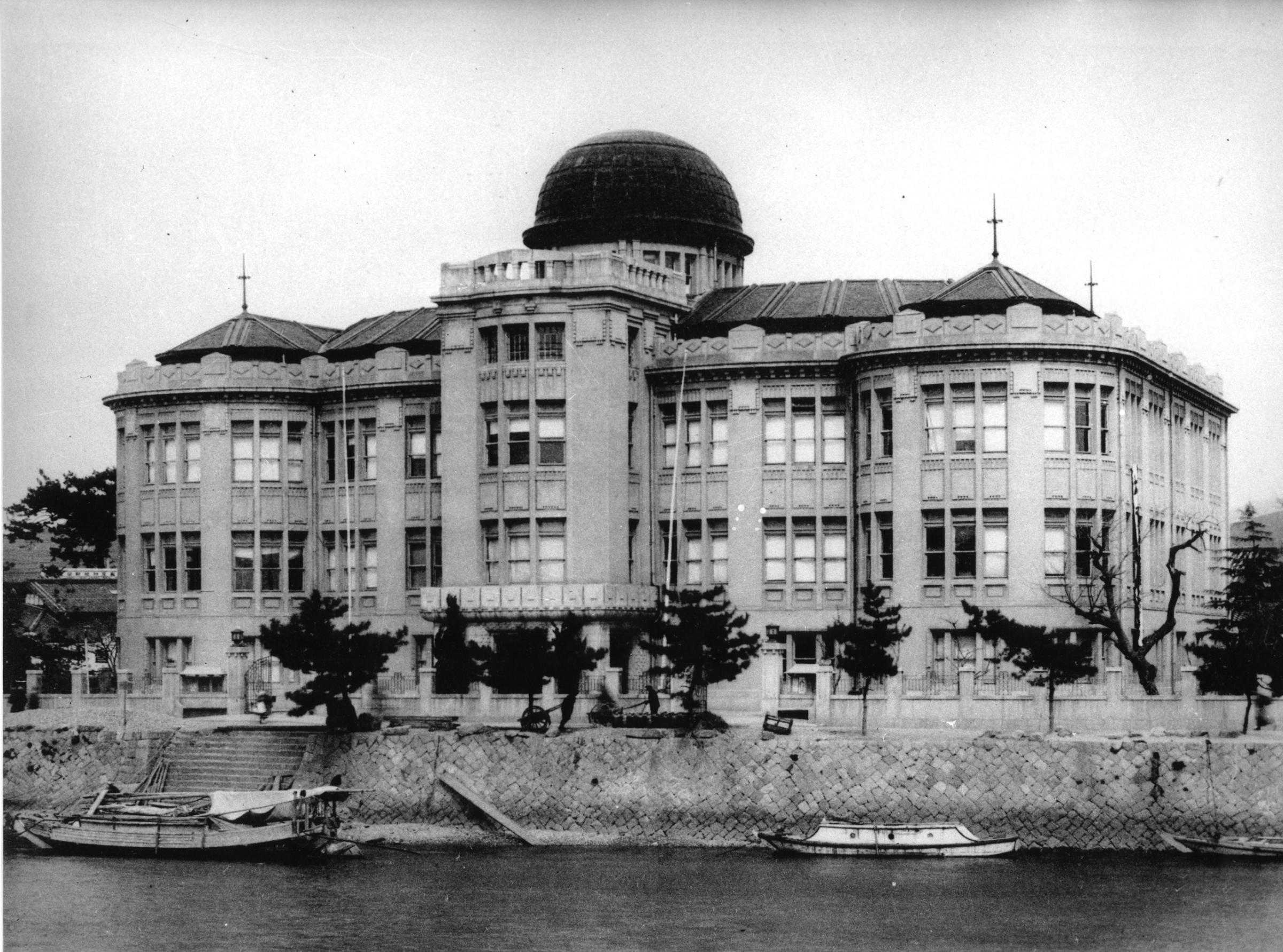

See What the Only Hiroshima Building to Outlast the Atomic Bomb Looks Like Today

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com