You know what was big in 1994? interactive TV. Seriously: Microsoft had all its A-listers up in that business, and I mean the triple-As, the heavy hitters. Nathan Myhrvold (later Microsoft’s CTO) was on the interactive-TV team. So was Rick Rashid (he founded Microsoft Research). So was Craig Mundie (currently senior adviser to the CEO).

And so was Satya Nadella, 48, who has been CEO of Microsoft since February 2014. “It was the greatest collection of IQ ever at Microsoft,” he says. “It was just amazing. We built a fully switched ATM network to the home. I used to live in an apartment right next to Microsoft, so I was one of the few guys who had video on demand in ’94 in my apartment. And I lived the future! Except we missed one big thing–called the Internet.”

You can learn several important things about Nadella from this short speech. One is that, like Microsoft founder Bill Gates, he’s a true nerd: it takes a true nerd to still be jazzed about interactive TV in 2016. Another is that he’s not particularly touchy or defensive about Microsoft’s dead ends and missed opportunities: he lives in reality, or as close to it as the CEO of Microsoft can get. And third, he really is a totally huge nerd, because only a huge nerd wouldn’t bother to explain that ATM in this context stands for asynchronous transfer mode and not automatic teller machine.

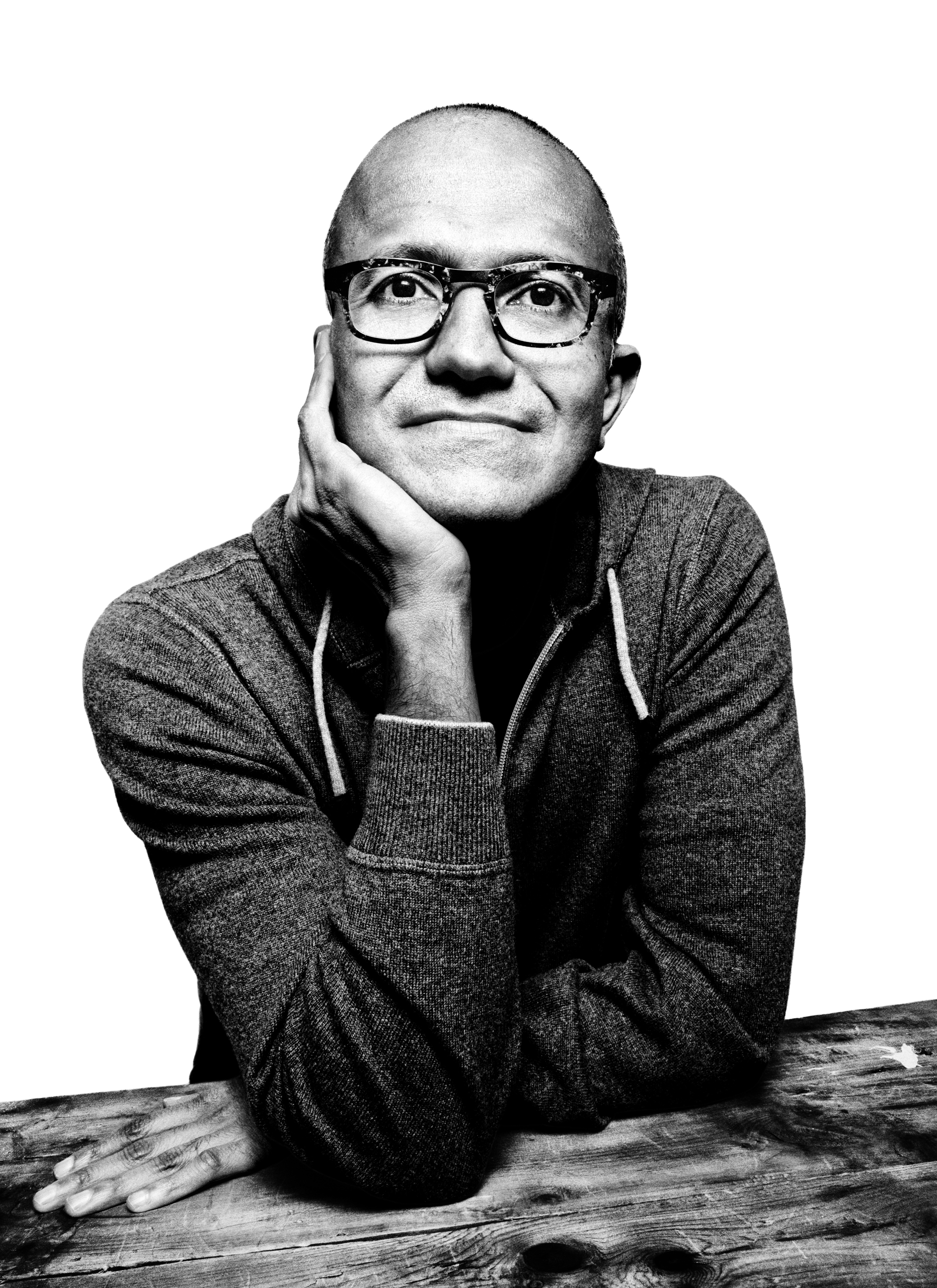

In person Nadella is a slender, tallish man–I’d put him at 5 ft. 11 in.–with close-cropped, barely there hair. Like Steve Jobs in his prime, he has a wiry, restless energy even when he’s sitting down. His most pronounced features are his jawline, which is prominent to the point of being heroic, and his mellifluous voice, which swoops up and down in a way that is not wholly unreminiscent of Julia Child’s. Nadella was born in Hyderabad, India, the son of a Marxist economist and a professor of Sanskrit. I met him in a conference room on the Microsoft campus, Building 34, in Redmond, Wash., where my rented Nissan was by a large margin the crappiest car in the parking lot. We talked about the year ahead.

Microsoft is not a company that one automatically associates with the year ahead, unless that year happens to be 1994. When Nadella took over, Microsoft was widely regarded as an aging warhorse kept alive by the profits from Windows and Office but incapable of bringing a seriously innovative product to market. It was the company that missed the Internet revolution (though not interactive TV!), the search revolution, the mobile revolution, the social revolution and the cloud revolution. It was the company of Zune, Vista and Kin.

But over the past year Nadella’s Microsoft has made a series of moves that have drawn torrents of if not praise then at least grudging respect from the tech press. It made news with gee-whiz demos like Skype Translator–real-time translation of voice calls–and HoloLens–an augmented-reality headset. Its Surface line of tablets and laptops is an impressive display of engineering done Apple-style–Microsoft makes both hardware and software–that is slowly but surely clawing a share of the tablet market away from Apple and Android. Microsoft’s cloud business (Nadella’s baby; his previous job title was executive vice president of the cloud and enterprise group) is second only to Amazon’s in market share.

Windows 10, released in July, has gotten good reviews and currently owns around 9% of the world’s desktops (overall Windows runs on about 90%). Microsoft’s stock is up 18% over the past year; by comparison Apple’s is nearly flat. On Oct. 23, Microsoft reached its all-time high, finally beating the high-water mark it set back in the dotcom golden age of 2000 (not adjusted for inflation, mind you, but it’s still worth two cheers). It feels unnatural even to type this, but Microsoft is hot.

When I asked Nadella what he felt were Microsoft’s top three wins in 2015, he chose Windows 10, the company’s cloud business and its expanded artificial-intelligence capability. This illustrates both why he is a CEO and why he is not a technology journalist: I wanted him to bring up HoloLens, which is much sexier than any of those. HoloLens is a wearable display that overlays the real world around you with digitally generated three-dimensional imagery that looks and moves and behaves like it’s part of reality–this is called augmented reality, which Nadella nerdishly abbreviates as AR. It’s a topic to which he is happy to pivot. “Up to now, throughout our computing history, we have essentially taken what has existed in the analog world and created a digital metaphor, the desktop being a great example of it,” Nadella says. “This is the first time where you’re taking the analog world and superimposing it with digital artifacts. We’ve always created mirror worlds. But now the world itself is a mirror.”

It’s early days–Nadella hopes to release a version to developers in 2016–but the potential applications are spectacular. You could build Minecraft structures that look like they’re sitting in your living room. (Nadella, maybe not coincidentally, acquired Minecraft developer Mojang in 2014 for $2.5 billion.) There’s a prototype combat game called Project X-Ray: “You’re fighting dragons that are coming out of your refrigerator and all kinds of things,” Nadella says. “It feels like a 3-D movie, but wow, it’s in your house.” (Wow is his go-to exclamation.) Companies could use HoloLens to train workers on virtual equipment. Med schools could train surgeons on virtual bodies. At your desk you could set up multiple virtual desktops that hang in the air around you.

Unlike full virtual-reality headsets like Oculus Rift, HoloLens is mobile–you can walk around wearing it. “One of the first times I said, ‘Oh wow, we’ve got to go all in,’ was when I saw the NASA demo for the first time,” Nadella says. “Think about it: if you’re a NASA scientist who worked on the Rover, their dream was always, ‘God, I want to be on Mars’ … then the output of where the Rover is is right in their office as a hologram. So they’re walking around the Martian terrain and examining the soil as if they’re there.”

HoloLens isn’t a single breakthrough, it’s a bunch of new technologies–eye tracking, motion sensing, 3-D imaging, shape recognition–mashed up together. As such it’s the product of a kind of risk taking and cross-company collaboration that haven’t always been typical at Microsoft. Microsoft is often cited as an example of the inertial malaise that takes over middle-aged technology companies rendered sclerotic by too much middle management and too much money. “When you are successful that means your existing concept is reinforced with your existing capability, and your culture reinforces those too,” Nadella says. “And so suddenly you have a new concept, and wow, your culture is fighting it, you don’t have capability for it, and so on.”

One way to beat that malaise is to create silos, companies within companies. In 2005 I spent a week at Microsoft studying the development of the Xbox 360, and that’s how they did it: they created a unit that was hermetically sealed off from the rest of the company, so that the culture couldn’t fight the concept. And it worked: the Xbox 360 was a strong product, and unlike anything Microsoft had ever made.

But that’s not how Nadella does innovation. “I fundamentally don’t believe that large, successful companies can be doing these sideshows,” he says. “You have to have the angst of birthing new concepts, which require new capability, and which require your culture to change as well. If you can’t do that then this Hail Mary, that somehow something carved out is going to save you, is actually a much riskier proposition.” Case in point: in December NASA sent HoloLens headsets up to the International Space Station so that the astronauts could use them to make Skype calls to Earth. (Microsoft bought Skype four years ago for $8.5 billion.) “Skype is holographic now. If we’d done this as some siloed thing with a few games, we wouldn’t have been able to do the unique things that we’re capable of, like inventing a new form of Skype for this new platform.” The Xbox 360 didn’t even run Windows. HoloLens runs Windows.

Not only does he decline to build silos, Nadella has overseen their demolition. Continuing a trend started in his predecessor Steve Ballmer’s era, he ran Microsoft’s existing business-unit structures through a blender. “The problem with business-unit structures in tech in particular is, none of our category definitions are long-lasting,” he says, “because no competition or innovation respects your category definitions. You need to reconflate tech. So what we have done is, we bust all our business units. We got rid of them all, and we went back into a functional organization. There’s one marketing team. There’s one business-development team. There are a couple of different engineering teams. Cortana, where is it built? If I draw an org chart for Cortana it will look like a graph, not like a hierarchical tree.” (Cortana is Microsoft’s virtual assistant, similar to Apple’s Siri.)

Of course there’s a reason people build business units in the first place, which is that when you’re having that many internal conversations between different parts of the company, that’s a lot of complexity to manage. Every time somebody comes up with a new idea, you’ve got 20 people weighing in on it. That’s 20 people who have a chance to say no. “That is, in fact, one of the big criticisms of our culture,” Nadella says. “There are so many people who can say no, very few people who can say yes … What’s at a premium for me is not people who say no but people who can make things happen.”

Though you can’t say yes to everything. As an innovation safety valve Nadella has revived something called the Garage, an internal space where staffers can tinker with random projects that don’t fit into current releases. Microsoft’s first hackathons have happened under Nadella, and a lot of Garage projects come out of those. “It’s self-formed teams, essentially, and they persist. Like one of the teams is taking OneNote and adding all kinds of natural-language capabilities into it, so that for example dyslexic kids can start reading. It’s not a sponsored project, but there are people from Microsoft Research, there are people from OneNote, people who have always dreamt of doing new forms of reading in Windows, all coming together and building this out. And what happens is, whatever is a hit in Garage, the next product team looks at it and says, oh, maybe I should put it in my product.”

One of Nadella’s mantras is, nobody at Microsoft owns the code base. You might own a particular use case, a particular scenario, but everybody owns the code collectively. In December, according to Nadella, Microsoft for the first time released a software update that patched all its devices in one go: PCs, tablets, phones, Xboxes, everything. “A lot of people tell me this is the first time there is even common vocabulary in the company,” he says. “Because after all we’re symbolic beings, and language helps.”

Nadella was right earlier: it doesn’t make a good photo op, but artificial intelligence was big in 2015, and it’s going to be bigger in 2016. Microsoft is pouring buckets of cash into AI and machine learning, and has been for decades–this is one revolution that Microsoft is actually demonstrably not late to. The impact of this investment is difficult to quantify, but you see it in subtly enriched functionality: applications learning and making decisions and generally behaving slightly less like software and slightly more like people.

A good example is Skype Translator, widely released in October, which translates (with varying degrees of success) voice conversations in English, French, German, Italian, Mandarin and Spanish. You see AI in Cortana and Clutter–a feature in Outlook that cleans up your email inbox based on past behavior–and in the shape recognition in HoloLens. In November Microsoft showed off software that can recognize human emotions from facial expressions. The idea is for AI to become less a mad-science research project and more just another building block available to the average programmer. “Hey, we’re the company that started with the BASIC interpreter,” Nadella says, referring to Microsoft’s very first product, a version of the programming language BASIC for the Altair 8800 microcomputer. “If this is the age of AI, we should be saying, let’s democratize machine learning and AI so that every developer who wants to write intelligent apps can do it.”

Microsoft doesn’t have a monopoly on this stuff. Facebook, Google, Amazon and IBM all announced significant developments in AI this fall, and not just announced them but open-sourced them–there’s a general industry-wide push to transform computing with AI, whether or not it makes a profit in the short term. “We’re in the beginning of what I call the third big platform, or runtime,” Nadella says, runtime being the moment when an application starts executing. “The first platform was the PC operating system–to me the phone was a big extension of it, but the same metaphor. The web was the second runtime, which was, all of the pages in the world got digitized, and I could navigate through them. The third runtime is this intelligent agent or personal assistant, and we’re in the very beginning of that phase. … It’s like that Netscape moment, or the Mosaic moment.”

This is a powerful idea. It used to be your OS that managed and structured your interactions with data; then it was your browser; increasingly it’s a coterie of artificially intelligent agents that will eventually understand not just your natural-language queries but your emotions and body language, to the point where they’re answering your questions before you ask them. The first time Nadella mentioned Cortana by name, a huge touchscreen on the wall of the conference room woke up, surprising even him, and presented us with the Bing search results for a garbled version of what he had just said–something about Cortana and the Navy. We’re not quite living the future, but we’re getting there.

Our conversation would not have been complete until I gave Nadella a hard time about Microsoft’s struggles in the smartphone market. There is broad agreement that personal computing is shifting tidally away from desktops and onto mobile devices. Apple’s share of this crucial space is 16%. Android’s is 81%. Microsoft’s is 2.2%, and that figure doesn’t appear to be growing. In 2013 Microsoft tried to buy its way in by acquiring Nokia’s cell-phone business; last summer it wrote off $7.6 billion on the deal, almost the entire purchase price, and laid off thousands of former Nokia employees. Even Ballmer–somewhat bizarrely, especially since he’s the one who bought Nokia–was overheard loudly criticizing Nadella’s mobile strategy during Microsoft’s annual shareholder meeting in December.

The issue doesn’t appear to fuss Nadella, but he doesn’t have an overwhelmingly convincing solution either. His point, basically, is that as long as Windows stays strong on other kinds of devices, people will eventually turn to Windows Mobile so their phones can be part of that same ecosystem. Likewise app developers will be turned on by the idea that they can write one app and have it run on the whole suite of Windows devices. “We recognize that in this form factor we have low share,” he says. “But we do have 110 million Windows 10 users who are on active devices today. We just upgraded all of Xbox to Windows 10. HoloLens is a Windows 10 computer. And we believe that it’s the network effect across all of these devices. That’s our strategy.” I ask him whether there’s a marketing piece, whether Microsoft might just not be cool enough to sell a product as personal as phones, but he is unintrigued by this line of inquiry. Though neither does he incinerate me with heat vision, the way Gates or Ballmer might have.

In fact if there’s one thing that makes Nadella the right person to stand watch over Microsoft’s middle age, it may actually be that he’s humbler and less ambitious than his predecessors. He’s more hip to nuance and compromise. He is not hell-bent on owning the world, because the world is too complex and fluid to be owned by anyone right now. It’s a lesson Nadella first learned in his interactive-TV phase. “These walled-garden approaches, sometimes you can make it through, right?” he says. “You could say today Facebook is doing it successfully. But there is an alternative, where you have a strategy which is more to ride that wave and then differentiate. That is perhaps the best sort of meta-learning for me.”

He’s not too proud to hedge his bets. Microsoft is putting markers down at all points on the technology food chain. It’s building phones and sticking doggedly with Windows Mobile, but it’s also putting key apps like Office and Cortana on iOS and Android, a heresy Nadella’s predecessor never sanctioned, and meanwhile it’s pushing HoloLens as the mobile platform of the future. “I’ll admit that we missed mobile as it’s understood today,” he says. “I don’t think we’re going to miss mobile as it’s going to be understood five years from now.” And even if Microsoft gets muscled out of the hardware, and the OS, and the applications, it can still own the cloud, where the data that all those things feed on lives.

Nadella is embracing the complexity of the moment: his fluid, flexible Microsoft is a response to an increasingly fluid, complex computing environment, what Nadella calls (with his engineer’s gift for not coining a phrase) a “heterogenous device environment.” Personal computing is no longer organized around a single solar center, the PC, orbited by subordinate planetary peripherals. Now it moves from device to device, from desktop to laptop to tablet to phone, and whichever one you’re holding at the moment is the center. “It’s more going to be about the mobility of the human experience across devices vs. just the mobility of any single device,” he says. “This is a lesson learned from our own PC past–I think we were more perhaps obsessed with just one device being the hub for all activity for all time to come.”

Nadella is playing the long game, where the object isn’t to run the table, it’s just to keep playing. “If there was Techmeme in 1975, we would have been on it every day, duking it out,” Nadella says, referring to a technology-news site popular in Silicon Valley. “In the middle of the ’80s we would have been on it with DOS. We would have been on it in the mid-’90s with Windows. And here we are in 2015 with cloud and AR. So now tell me: How many companies were there then who are now here in a relevant way? Not just at the bottom-line profit. Not in having one great research institute. No: but duking it out.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com