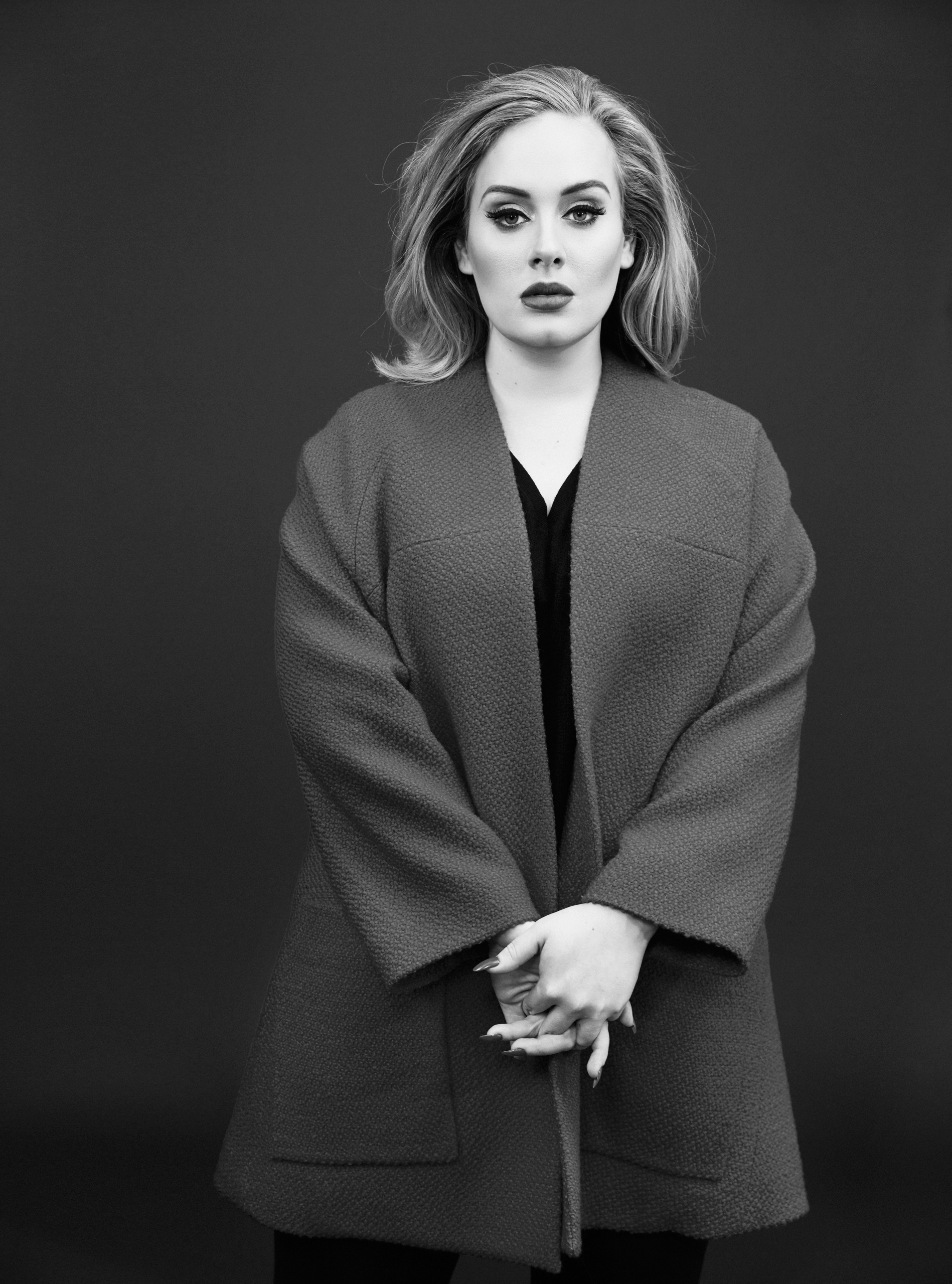

On a chilly November night, Adele takes the stage at Radio City Music Hall in Manhattan for her first show in the U.S. in four years. It’s also the first stop on a stateside publicity tour to promote her new album, 25. After singing her No. 1 smash “Hello,” an orchestral ballad that aches with regret, she kicks off her shoes center stage and sighs. “How are you?” Adele asks the audience. “Are you all O.K.?” The crowd cheers. “I’m sorry,” she says. “I’ve got gas because I’m nervous.” Laughter erupts in the hall.

“I don’t think she even realizes how beloved she is,” the woman next to me says to her friend in a loud whisper. “She’s literally a national treasure.”

Judging by Adele’s commercial success, at least, this is less opinion than fact. Prognosticators anticipated that 25 might sell a million copies in its first week, an extraordinary figure in an anemic music industry that has seen physical record sales wither. Selling 2 million units would be miraculous. The last time that happened was in 2000, when ’N Sync’s blockbuster No Strings Attached sold 2.42 million copies—albeit long before streaming services obviated the need to buy albums. But by the first week’s end, Adele had sold 3.38 million copies of 25, making it the biggest sales week in history. Then sales passed another million the following week. Then another.

Adele can’t account for how she pulled off the seemingly impossible. Reclined on the floor of her hotel room a few days after the concert, she says she has “no idea” why she’s sold so many records. “It’s a bit ridiculous. I’m not even from America.” The 27-year-old sets down her cup of tea, brightening. “Maybe they think I’m related to the Queen. Americans are obsessed with the royal family.”

This is a little disingenuous, but only a little. Her last album, 21, was the best-selling record of 2011 and ’12, racking up a staggering 30 million copies worldwide. The lead single on 25, “Hello,” also shattered records: its music video was viewed at a rate of 1.6 million times per hour on YouTube. It stood to reason that she’d do good business. Still, Adele’s return to the spotlight is unlike anything the music industry has ever seen. Says Keith Caulfield, co-director of charts at Billboard, which tallies music sales: “She’s a unicorn.” Even compared with 2014’s biggest blockbuster—Taylor Swift’s 1989, which sold less than half as many copies during its debut week—that isn’t hyperbole.

Adele, of course, is more than a set of stratospheric numbers. In a stunted pop economy in which her contemporaries try to sound simultaneously like each other and like what might be trending next, Adele does the opposite: she sounds like the past. Her music is dignified, even stately, cutting across demographics. On 25, as on her previous releases, she cements her reputation as pop’s oldest soul with songs that are intimate and simple.

And then there’s the voice.

“She studied Ella Fitzgerald and Nat King Cole—all the old greats,” says Ryan Tedder, lead singer of the pop-rock outfit OneRepublic, who wrote two singles with Adele on 21. “You have a voice that’s been trained on the greatest singers of all time.” That voice is a mighty instrument, clean and muscular. But most of all, says Tedder, who also co-wrote the ballad “Remedy” on 25, Adele’s appeal is her authenticity. “When she writes a song,” he says, “it doesn’t sound like songwriting by a committee. It’s just her.”

When you talk to people about Adele, pretty much everyone uses the word authentic sooner or later. But over the course of a week with her, it’s not one she uses to describe herself or her music. Nor is she into other industry jargon. At one point, she volunteers that she hates the word brand, for example. “They all use that word,” she says. “It makes me sound like a fabric softener, or a packet of crisps.”

Unlike nearly all her peers, Adele has no product-endorsement deals. She seems uninterested in the contemporary practice of working to maintain a specific image. She just doesn’t want to be perceived as a jerk. “Some artists, the bigger they get, the more horrible they get, and the more unlikable,” she says. “I don’t care if you make an amazing album—if I don’t like you, I ain’t getting your record. I don’t want you being played in my house if I think you’re a bastard.”

Adele will be played in a lot of houses in 2016. Her voice has the impact of a thousand tons of bricks. The zeitgeist can’t seem to get enough—the memes spawned by “Hello” alone were numerous enough to clog social media for weeks. Yet she’s the only pop star you can listen to with your grandma. That’s the reason she can dominate as fully as she does: Adele bridges pop music’s past and its future.

In person, Adele is frank and funny, peppering her speech with profanity and self-deprecating asides. Perhaps that’s why it’s startling to register how young she still is. 25, like the two albums before, is named for the age she was when she recorded it. Born Adele Laurie Blue Adkins and raised in the working-class London neighborhood of Tottenham by a single mom, she recalls her childhood through the lens of being a new mother. Her son Angelo is 3. “The environment in which my kid is growing up couldn’t be further away from the way I grew up,” she says. “But there was never any embarrassment about showing love in my family.”

Early on, she was inspired by R&B artists such as Lauryn Hill and Alicia Keys, along with legends like Etta James. At 14, she earned a spot at the BRIT School, an elite performing-arts school that also counts Amy Winehouse and Leona Lewis as alumnae. She was scouted on MySpace and signed with indie label XL at age 18. When she began recording her debut album, 19, her expectations were low. “I was a brand-new artist,” she says. “No one cared.” But a warm reception in the U.K. and a high-profile performance on Saturday Night Live in 2008 showcasing her single “Chasing Pavements” garnered buzz in the U.S. That winter, she won the Grammy for Best New Artist.

Superstardom came the following year when she released another single, “Rolling in the Deep,” a stomping anthem that set the tone for the record that followed and topped charts around the world. Released in 2011, 21 was largely about the end of a relationship that hit on classic themes of heartache and empowerment. Her songs often sounded simpler than they were. The easy melody and spare production of a track like “Someone Like You,” for instance, makes it seem universal. Yet it’s also an emotionally complex piece of writing.

By the time Adele was a household name, she was ready for some time off. After giving birth, she did the most radical thing an artist at her level could do: she went mostly dark to spend time with her boyfriend, charity executive Simon Konecki, and their son Angelo. “I was very conscious to make sure that our bond was strong and unbreakable,” she says. “I had to get to that point before I’d come back.”

This left her with little in the way of material for a new album, however. First she tried writing songs about motherhood, most of which she tossed. “I loved it,” she says “For me, it was great. Better than 25. But he’s the light of my life—not anyone else’s.” She didn’t want to write about the issues in her partnership with Konecki. “We’re in a grownup, adult, mature relationship,” she says. “I didn’t want to write about us, because I didn’t want to make us feel uncomfortable.” Nor did she want to resort to shallow material. “Can you imagine if I was singing about texting?” She cackles. “You would never get me singing about having a drink in the club.”

It wasn’t until Adele turned the lens back on herself that she was able to make progress. “That’s when I decided to write about myself and how I make myself feel, rather than how other people make me feel,” she says. She also decided not to rush it. “It doesn’t matter how long it takes,” she says. “You’re only as good as your next record.”

This is also the DNA of her songs on a compositional level. Much of what’s on the radio is cooked up by A-list producers and songwriters who churn out hooks, snippets of melody, lyrics and song concepts. Their work is then mined for precious No. 1 hits. It’s a sound rooted in the late ’90s, when artists like Britney Spears and the Backstreet Boys began recording tracks written by superproducers like Max Martin and his Stockholm team of songwriters, who expertly blended American R&B and European dance music. Nearly two decades later, Martin is still shaping hits for artists including Taylor Swift and Katy Perry.

Top songs are also often written to track, which means a producer makes a beat, then a songwriter listens to it and attempts to generate words that fit that beat, sometimes singing nonsense until the language begins to take shape. It’s more about how lyrics sound than what they mean. This has become a bedrock part of the industry, as laid out in John Seabrook’s recent book The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory. And it’s how you end up with something like Ariana Grande’s dance-pop confection “Break Free”: “I only wanna die alive … Now that I’ve become who I really am.”

While every artist has a different level of involvement with the composition of their songs—Swift writes her own material, for example, and wrote her 2010 album Speak Now without the help of any other songwriters—there remains a widespread sensitivity to hit potential that guides the process. The songs on the radio are catchy because they’re engineered to be. “Mathematical songwriting” is how Tedder describes it. “It works if you’re someone who gets called on to write hits,” he says. “But it doesn’t lead you to a place like Adele. That sh-t doesn’t work on her.”

Adele’s dismissal of this is a big part of why she reminds people of the way music used to sound—she writes it the way music used to be written, decades ago, before that teen-pop boom of the late ’90s. “I’m not precious about writing credits—it’s whatever makes the best song,” she says. “But I can’t do that. I can’t write a song based on a track.” Her songs aren’t a Frankenstein’s monster of her best ideas, either. “I write a song from beginning to end,” she says. “I don’t go in sections. It’s a story.” Even though she, too, recorded songs for 25 with Martin, their cut—“Send My Love (To Your New Lover)”—doesn’t have the stitched-together feel of many radio hits.

Greg Kurstin, who co-wrote and produced “Hello,” says Adele’s process is increasingly rare. “She would start out with actual lyrics,” he says. “I don’t see that in the pop world.” Accordingly, Adele’s songs stand out against much of what’s popular now. “I’m not saying my album is incredible, but there’s conviction in it,” she says. “And I believe the f-ck out of myself on this album.”

A few days later, Adele is in the green room of the Today show. By this point, 25—five days after its release—has already been cemented as the fastest-selling record since Nielsen began tracking first-week sales in 1991, breezing past all previous record holders, including albums from ’N Sync, Britney Spears and Eminem. Accordingly, the mood is high among her entourage. She is being primped and prodded by a swarm of makeup artists and hairstylists and looks every bit a diva. But when a dog barks in the hallway, she rushes out to pet it, barefoot in her Burberry gown. Suddenly her manager, Jonathan Dickins, rushes in, calling to Adele’s stylist, Gaelle Paul: “Gaelle! Gaelle! We’ve got to get a new frock! The dog’s had a wee on this one! Where’s the Givenchy?” Paul, panicked, races out of the room. Once she’s gone, Dickins cracks up—it was a prank.

A few minutes later, Adele takes the stage to perform “Million Years Ago,” a nostalgic ballad. As soon as she starts to sing, the room falls silent. It’s a haunting song, dirgelike in its starkness. Halfway through, one of the producers dabs at his eyes. The artist who’s endlessly self-deprecating in conversation is instantly commanding when she opens her mouth to sing.

Unlike many of her contemporaries who use social media to telegraph relatability, Adele thinks the web is a big part of why stars get oversaturated. Not to mention artistically distracted. “It’s ridiculous that high-profile people have that much access to the public,” she says. “How am I supposed to write a real record if I’m waiting for half a million likes on a photo? That ain’t real.”

She’s not a Luddite, but there is a nostalgia that even comes across in her music. “Hello” is a song about calling someone on the phone, not Snapchatting them. “People were going on about that I was calling on a landline,” she says. “I still use landlines.” Much was made of the fact that she uses a flip phone in the song’s sepia-hued video, but that, too, was conscious. “It is so unlikely I’d have a flip phone in this day and age,” she says. “Call me old-fashioned, call me ignorant, but whatever. Take it or leave it.”

This ethos has guided her in other ways too. When reports surfaced that 25 would not be immediately available on streaming services such as Spotify or Apple Music, there was criticism from fans and industry insiders. She says she was under pressure from both sides—to stream and not to. (Artists, even mega-stars, make considerably less streaming their music as opposed to selling it.) “I don’t use streaming,” she says. “I buy my music. I download it, and I buy a physical [copy] just to make up for the fact that someone else somewhere isn’t. It’s a bit disposable, streaming.” How much her decision helped boost her sales is tough to quantify. “I know that streaming music is the future, but it’s not the only way to consume music,” she says. She believes “music should be an event.” (25 could yet come to streaming services in 2016.)

Her decision recalls Swift’s removal of her music from Spotify in 2014 and subsequent open letter to Apple asking that the world’s biggest music retailer change its policies on how artists are compensated, which Adele says she admired. “It was amazing,” she says. “I love her—how powerful she is. We’ll get lumped together now because of it, but I think we would both feel the ability to say yes or no to things even if we weren’t successful.”

This is important to her: the ability to make her own decisions and work at her own pace. She could have released 25 earlier to make it eligible for the 2016 Grammys, but instead it arrived when she was ready. In an era when artists release albums like clockwork and every morsel of information is meted out to generate news, Adele thinks we should slow down. “The speed with which we discover and get over things is too fast,” she says. “I’m frightened that I’m not going to be able to relate to my kid.”

The artist who has forged an extraordinary career by spinning her vulnerability out to the world is especially tender when she talks about Angelo. “He makes me so proud of myself,” she says. “He makes me like myself so much. And I’ve always liked myself—I’ve never not liked myself. I don’t have hang-ups like that. But I’m so proud of myself that I made him.” She plans to bring him with her on tour in 2016, which she says will be an ambitious production. “I really would like to fly through the arena for the beginning, but no one’s having it,” she says, laughing.

Back at her hotel for a photo shoot, someone suggests playing Beyoncé might set the mood. As soon as the opening chords of “Love on Top” start to play, Adele starts to dance. “Good choice,” she says. Then Angelo streams through the room, a whirlwind of energy. Eventually, he joins her in front of the camera, so the photographer moves closer, shooting her from the neck up, while Angelo sits beside her, out of the shot. He gazes up at her as she looks into the camera, then reaches for her hand. She grips it tightly. Her eyes light up and her mouth curves into the faintest smile.

This appears in the December 28, 2015 issue of TIME.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com