This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

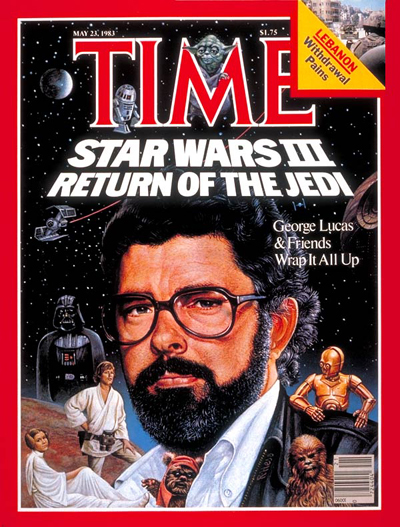

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away… these famous opening words of the original Star Wars movie set the story in a historical vacuum. In reality, of course, Star Wars and the subsequent films in its franchise are not timeless; their production and reception are rooted in multiple historical contexts. Creator George Lucas has acknowledged that he derived artistic inspiration for his Star Wars universe from a variety of cultural sources, including the writings of Joseph Campbell, the films of Akira Kurosawa and John Ford, and the psychological theories of Carl Jung. Recent books explain how the Vietnam War and antiwar politics also shaped the original 1977 film (one even identifies Richard Nixon as the model for Emperor Palpatine).

The Star Wars movies also are part of a historical continuum of nearly two centuries of commercial entertainment for American children. Core thematic, character, and plot elements in both trilogies borrow from formulas constructed for children’s literature in the United States during the mid-nineteenth century. These formulas were created at a time when businesses, parents, and children were negotiating over the emerging relationships between the nation’s young people and its commercial cultures. Their persistence suggests that even as the quantity of entertainment produced for children has expanded greatly since that time, the tensions surrounding this practice have remained relatively static.

Nineteenth-century influences particularly factor into the construction of the protagonists in the Star Wars films. Luke Skywalker, the central character in the original trilogy, undertakes a quest to help Princess Leia and ultimately overthrow the Empire in a story that follows literary models dating back to the ancient tales of Gilgamesh and Odysseus. Anakin Skywalker, whose descent from Jedi prodigy to Darth Vader is the focus of the second trilogy, also follows a narrative trajectory that dates back to ancient times. Yet Lucas’s choice to employ juvenile protagonists follows a practice only introduced into Anglo-American fiction during the 1850s by books such as Tom Brown’s Schooldays and Oliver Optic’s Boat Club series. Before that time, most American literature presented young people as victims or unwitting beneficiaries of adult decisions; only misbehaving children served as agents of change, and in those cases the consequences were usually dire.

This shift toward more positive models of active juvenile characters in the mid-nineteenth century was a response to the combination of rapid urbanization and market expansion occurring in the United States during this period. These changes gave city children greater access to scandalous entertainments such as crime newspapers and sensational fiction, and as a result sales and circulation numbers declined for the didactic, often evangelical genres of American children’s books and magazines established earlier in the century. Parents and moral reformers expressed dismay in the media about this reading trend during and immediately after the Civil War (Anthony Comstock’s crusade against dime novels during the 1870s was part of this broader trend), and in response reputable publishers and their customers gradually converged upon new formulas for children’s literature. Postwar stories in popular children’s magazines such as The Youth’s Companion and St. Nicholas were among the earliest to appeal directly to American children’s desire to be entertained, yet they also retained the Protestant moral standards demanded by adult customers striving to retain control over children’s exposure to commercial influences.

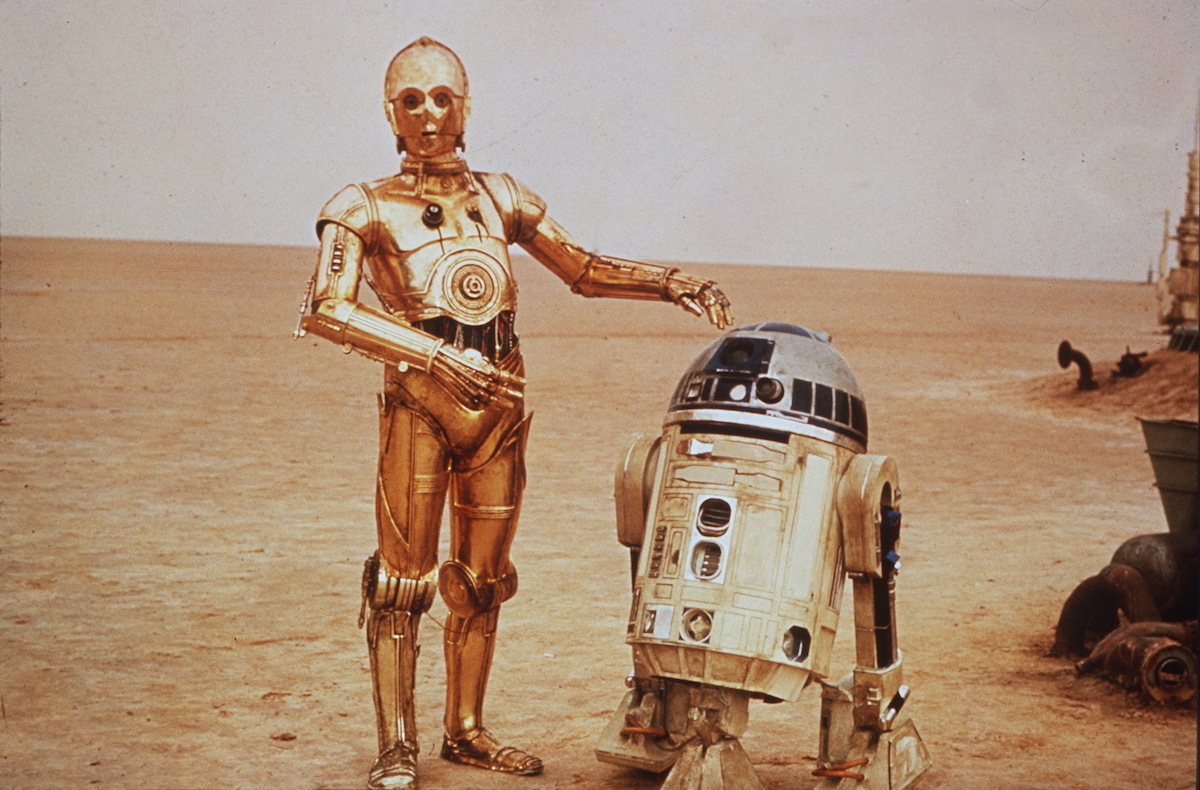

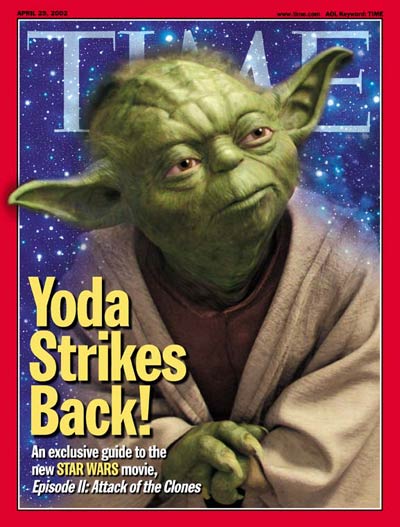

One of the crucial goals of these new formulas was to nurture ways of entertaining children that still protected them from the perceived physical and moral dangers of exposure to unregulated urban commerce. Consequently, most post-Civil War American children’s literature romanticized rural life and expressed misgivings about the propriety of young people living in cities. A century later, the Star Wars movies maintained these perspectives. The stories of Luke and Anakin’s migrations from the hinterland of Tatooine into the heart of the Empire (or in Anakin’s case, the Republic) parallel those of young men traveling from countryside to city that regularly filled the pages of the Companion and St. Nicholas from the 1870s through the 1890s. In both cases, cities are seats of corruption, while more isolated environments are places of safety, learning, and contentment for young people. Luke begins his training with Obi-Wan Kenobi on Tatooine and culminates it with Yoda on the similarly remote planet of Dagobah. Even Anakin and Padmé’s romance in Attack of the Clones occurs on the lush peripheral planet of Naboo. Although this terribly awkward storyline addresses a subject generally not incorporated into either children’s literature or Star Wars movies, it reinforces a broader formulaic message that impatient and overly ambitious young men’s desire to engage in the dangerous complexities of life beyond their rural oases jeopardizes their happiness and safety.

Indeed, the impatience of Luke and arrogance of Anakin in the Star Wars films mirror the types of dangerous traits that late nineteenth-century authors embedded in their young male protagonists. In both the movies and the earlier children’s stories, such flaws served to highlight the susceptibility of young people’s inchoate moral characters to the dangers of unregulated urban and industrial cultures. Sometimes, as in the original Star Wars trilogy, the young man’s education and skills – particularly technological skills, such as Luke’s expertise as a pilot – enable him to transcend the temptations of immorality. Other stories portray promising young men like Anakin descending into corruption and death.

Identifying these and other parallels between the Star Wars films and nineteenth-century children’s literature is more than just a fun parlor game for history and sci-fi nerds. It’s an indication of how little the moral expectations for children’s entertainment changed over the course of 150 years, even as the means of delivering that entertainment have increased so dramatically. These expectations derived largely from families seeking to shape the nature of their children’s consuming habits, and they predate and survive the twentieth-century expansions of corporate marketing to children that so many commentators have bemoaned. Thus when parents like me walk into a store and complain about the conflicts that omnipresent Star Wars merchandise create with children who beg for the newest action figure or t-shirt, we can place some of the blame on Disney. But perhaps we should also assign some of the responsibility – at least for the nature of those products – to ourselves.

Paul Ringel is an Associate Professor of History at High Point University in North Carolina. His book, Commercializing Childhood: Children’s Magazines, Urban Gentility, and the Ideal of the American Child, 1823-1918, was published in October 2015.

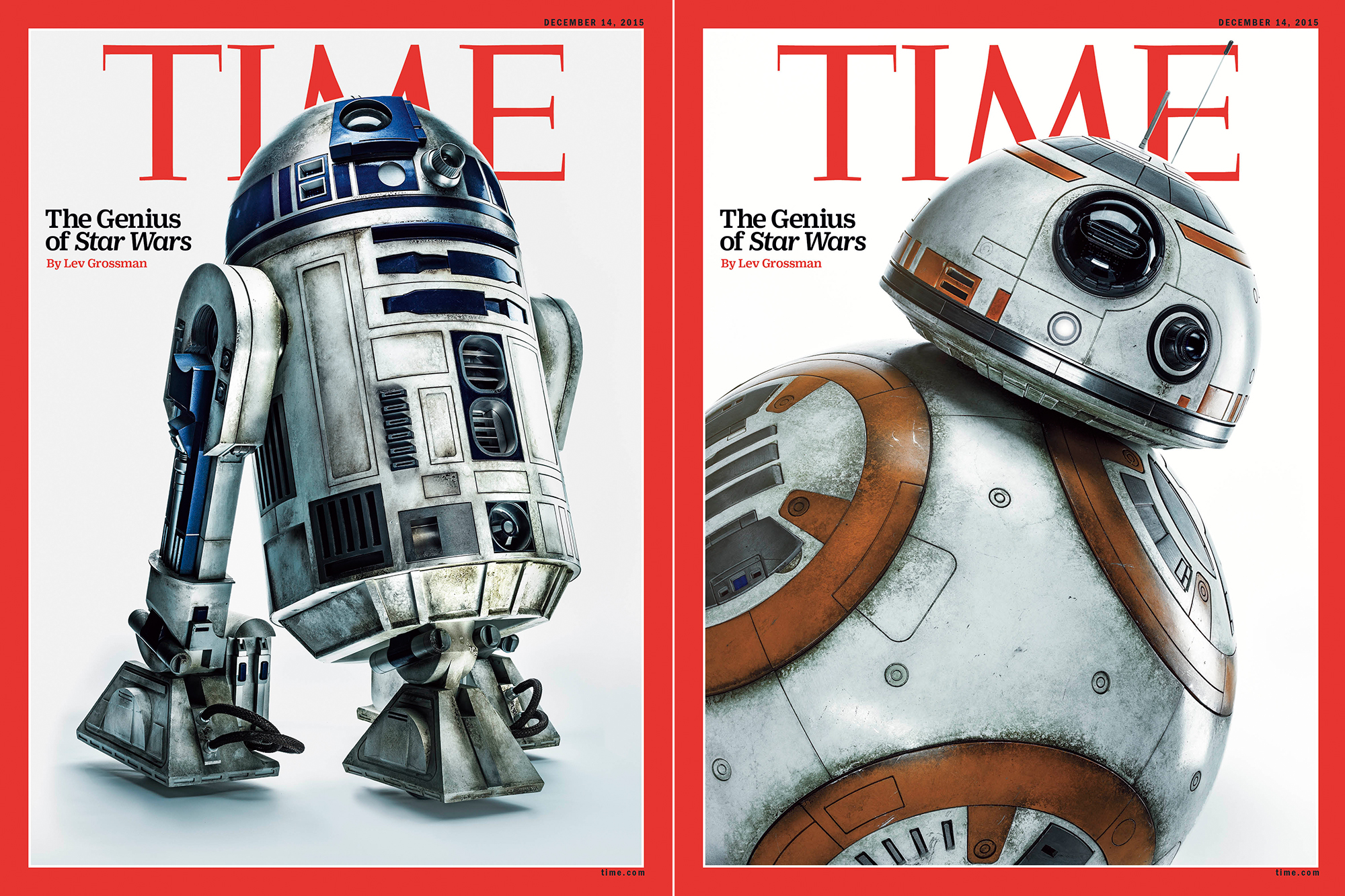

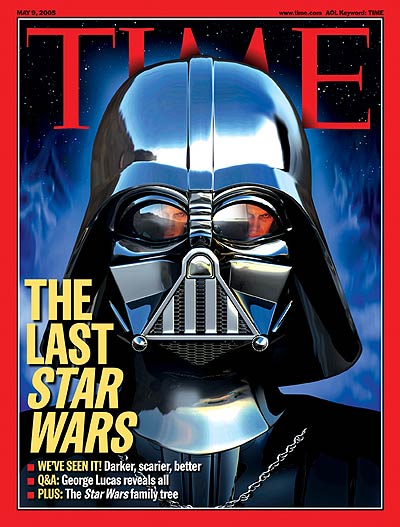

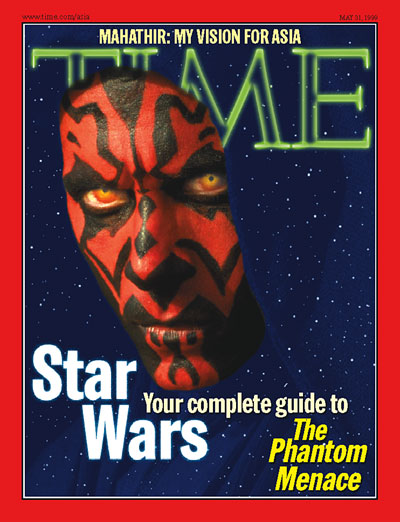

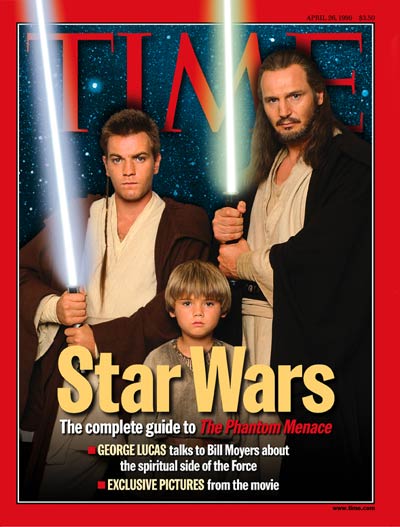

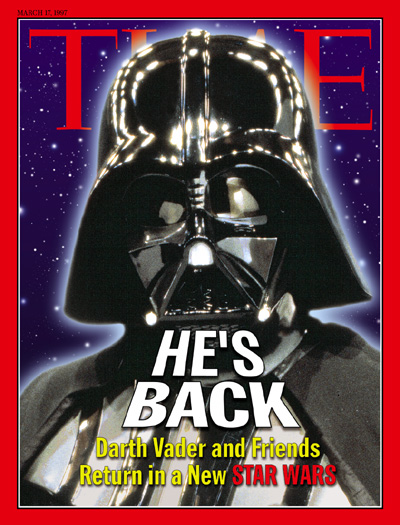

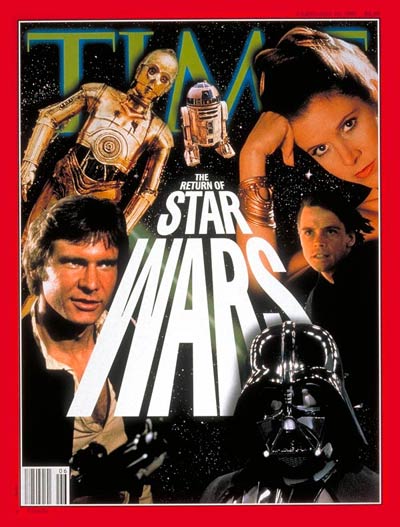

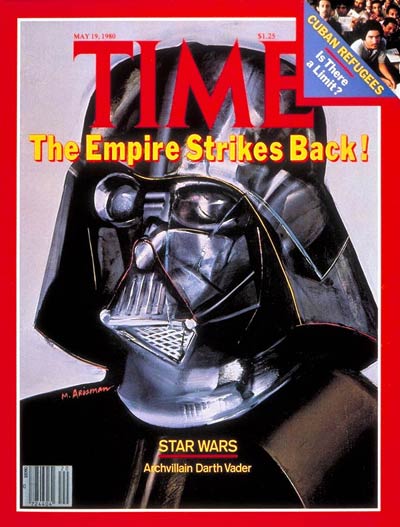

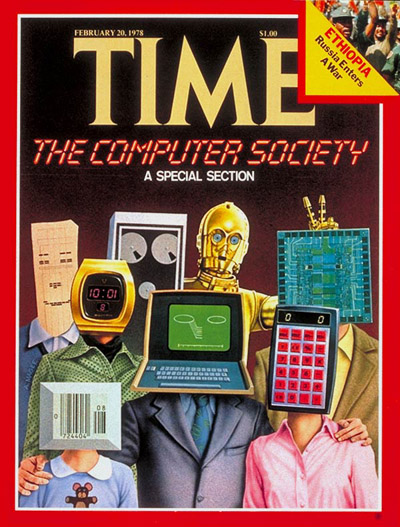

See Every Star Wars Cover in TIME Magazine History

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Introducing the 2025 Closers

Contact us at letters@time.com