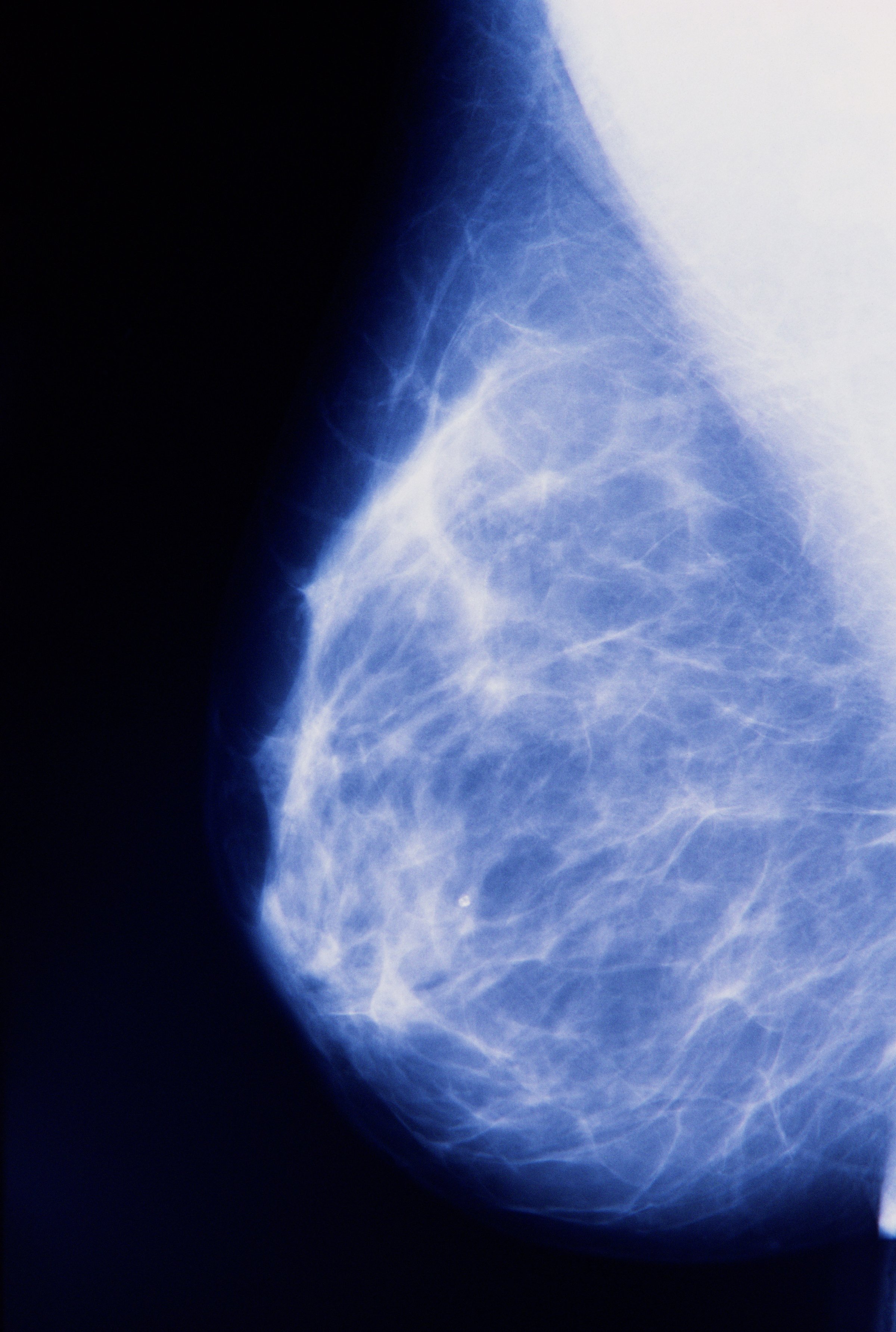

Each year, about 16% of women getting their first mammogram will get at false positive result. That means their doctors will call them back for some additional testing — more screening, or a biopsy — because they think they found something suspicious on the image.

As the name implies, most of these turn out to be nothing. But a new study suggests that false-positive results may not be meaningless. Reporting Wednesday in the journal Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, Louise Henderson from the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and her colleagues found that false positives might be more informative than previously thought.

MORE: Why Doctors Are Rethinking Breast Cancer

They analyzed data from nearly 1.3 million women who had mammograms done in the 1990s and 2000s. Women who had false positive readings showed a 39% higher risk of developing breast cancer in the next decade compared to women who didn’t. Henderson says that the findings do not suggest that women who get false positives are more likely to develop cancer, however. Because of the incredible volume of screening in the U.S., rates of false positives are very high. So the absolute risk of breast cancer for women with these results remains small.

“I wouldn’t say that if you have a false positive that you are going to go on to have cancer,” she says. Rather, says Henderson, “it’s a marker for something suspicious.”

MORE: Why Doctors Are Rethinking Breast Cancer

Henderson says that marker could be worth incorporating into the information that doctors use to predict a woman’s risk for the disease. These factors already include things such as her family history of breast cancer, her age, and the density of her breast tissue. Studies have shown that women with denser breasts tend to have a higher risk of getting cancer, and Henderson found the same pattern in this study. Adding the information about false positives could help doctors to refine their ability to predict breast cancer risk.

“I do hope that radiologists might eventually have a risk-prediction tool that says if a woman is a certain age, has dense breasts and has a false-positive mammogram, that would guide them to a different approach for how they recommend further screening for her,” says Henderson. “But we’re not at that point yet.”

Her study did not analyze whether the suspicious lesions that prompted the false positive, for example, matched the location of an eventual breast cancer tumor. That would tell doctors that the false positives might be worth tracking in more detail.

In the meantime, women with false positive results shouldn’t assume they are headed for a cancer diagnosis.

“The false positive results should really be a piece of the puzzle in terms of trying to predict breast cancer risk,” says Henderson. “It needs to be used in conjunction with other risk factors.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com