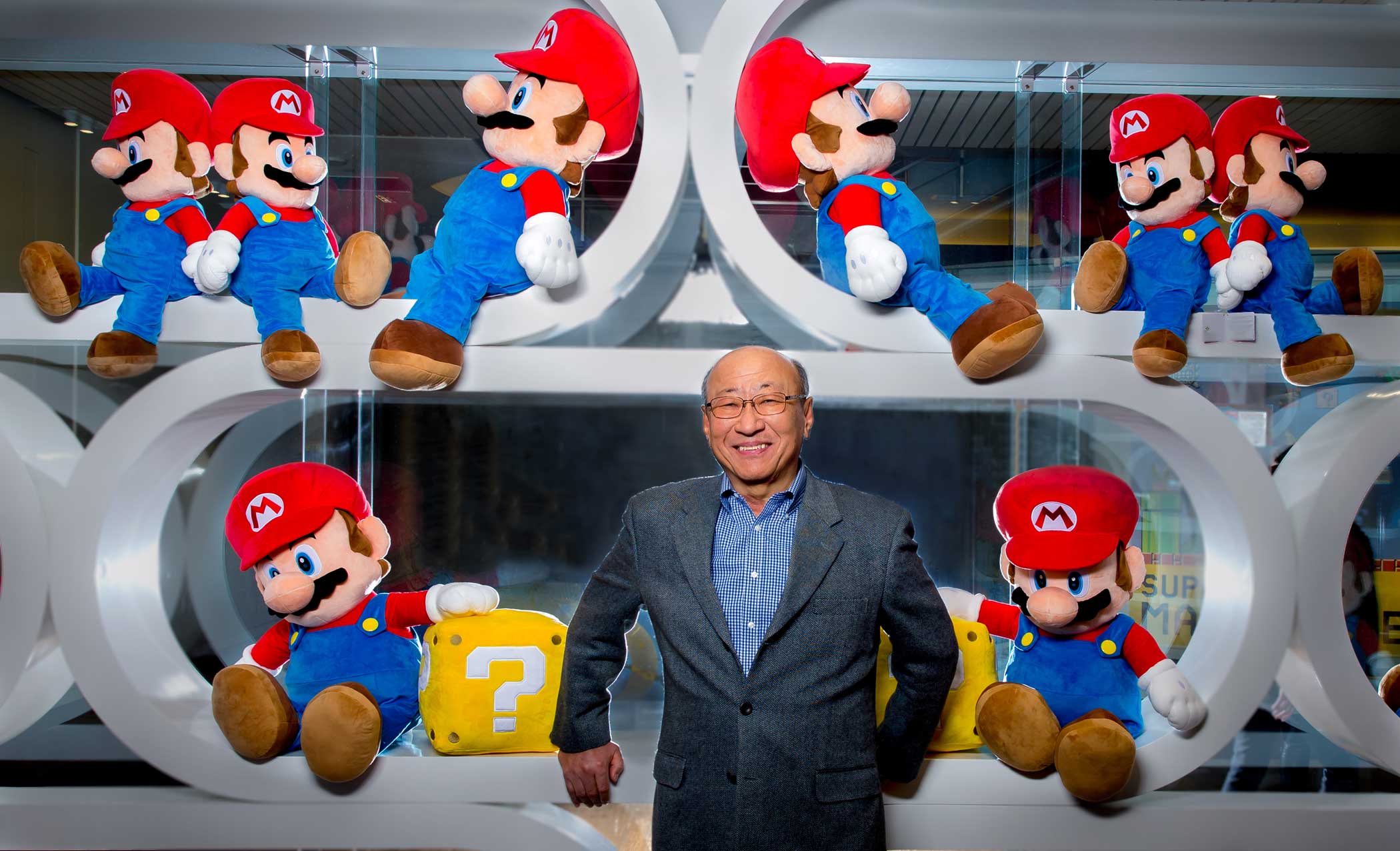

Tatsumi Kimishima didn’t go looking for a job at Nintendo. To hear the former banker tell it, he was drafted.

The 65-year-old, who took over running the iconic games company in September, recalls being summoned to the firm’s headquarters some fifteen years ago. He took a bullet train to meet with Hiroshi Yamauchi, the legendary chief who’d transformed Nintendo from a maker of playing cards into a global entertainment juggernaut, from Tokyo to headquarters in Kyoto. “Not the current building, but the old one,” says Kimishima, meaning the company’s main office from 1959 to 2000, near Kyoto’s Toba-kaidō railway station. After a brief conversation, Yamauchi informed Kimishima he’d be starting in a month.

Kimishima now finds himself at the helm of Nintendo as it enters a period of a transformation by no means certain. The 126-year-old maker of beloved characters like Mario, Donkey Kong and Zelda has struggled with its core business in recent years. Its Wii U console, successor to the blockbuster Wii, has sold about 11 million units since its launch in 2012. (From 2006 to 2014, by comparison, Nintendo sold more than 100 million Wiis.) The company has suffered layoffs and losses as pressure from critics to radically change course mounted. In March of this year, then-president Satoru Iwata announced the company would do so by designing games for mobile devices for the first time and revealed Nintendo was working on a new console. But in July, Iwata—the driving force behind some of the company’s most successful innovations—died unexpectedly from cancer.

After a difficult period of mourning for the company, Kimishima has turned to securing a future for Nintendo. Little known outside the firm, he talked to TIME exclusively about his plans for the company. What becomes clear in wide-ranging conversation is that he’s much more than the taciturn business leader many portrayed him to be in September—and that may be exactly what Nintendo needs now. (Click here for a lightly edited transcript of the conversation.)

Kimishima arrived at Nintendo in the early-2000s, during the ascent of Pokémon. A handheld game about snatching cartoon creatures and training them to do battle, it had launched in Japan a few years earlier and its popularity was growing in the United States. Nintendo boss Yamauchi was keen to spread the brand worldwide and establish a Pokémon subsidiary in the West. His strategy: appoint an emissary with significant business savvy from outside the games industry.

Kimishima had devoted nearly three decades to helping lead Japan’s Sanwa Bank, at the time one of the most profitable financial institutions in the world. He’d shown himself resourceful and adaptable: His rise included turns as head of public relations and as a management planning lead posted to the U.S. At 38, Kimishima became president of the company union, where he says he had to make decisions on behalf of more than 10,000 people, then figure out how to push those ideas through a 12-person executive committee. Yamauchi was interested in Kimishima, “based on my unusual banking history,” he says.

Their first meeting, during which Yamauchi laid out his strategy for the company and hopes for Pokémon, lasted an hour. “It was much more of a one-way conversation,” remembers Kimishima. When he finally got a word in, it was to confess that the only Pokémon he knew was Pikachu, the franchise’s lemon-hued, mouse-like mascot. “And Mr. Yamauchi quickly said back to me, ‘Actually, I don’t know much about Pokémon either,'” says Kimishima, laughing. “I don’t think he was being entirely honest.”

When the hour was up, Kimishima says he was all but given marching orders. “Without waiting for any sort of reply from me, Mr. Yamauchi said ‘Come to Nintendo next month, I want you to start working on Pokémon.’ Since I had spoken barely a word during the interview, I was quite surprised.”

That kind of quick, farsighted decision-making became a hallmark of Kimishima’s own career at Nintendo. After joining The Pokémon Company as its chief financial officer in late 2000, he left in 2002 to become president of Nintendo of America, simultaneously joining the company’s board of directors. A few years later, he became the American branch’s chief executive officer. And in 2013, he was promoted again to managing director of the company, moving back to Japan, where he served until September.

This trajectory, while impressive, doesn’t look much like his predecessor’s. Satoru Iwata, a games industry icon, was the highly visible face of the company for a decade. Warm and humble, he seemed to embody and radiate Nintendo’s friendly aesthetic, even as the company hit its recent rough patch. His background as a games creator was reflected in innovations like the dual-screen Nintendo DS handheld and motion-controlled Wii. Comparing Iwata to Steve Jobs or Elon Musk, though they differ radically in personal style, is not a stretch.

Kimishima seems by contrast the quintessential businessman, low-key and difficult to scan. Until his appointment to replace Iwata, little had been written about him. Western histories of the company that mention him do so only in passing. Not surprisingly, his appointment was greeted with some consternation, if not confusion. Many outlets mistakenly billed him as head of human resources, igniting prognostications of bean-counting doom. (While Kimishima was appointed to manage Nintendo HR in 2014, his primary role remained managing director of the company.)

Kimishima’s colleagues say these fears are unwarranted. He is, says Nintendo of America president Reggie Fils-Aimé, “a master at navigating all of the various Nintendo constituents to make big things happen.” Fils-Aimé succeeded Kimishima as president of Nintendo’s American branch in 2006, but says the two began working closely when Fils-Aimé came on as Nintendo’s executive vice president of sales and marketing in 2003. He waves off media reactions to the appointment as either conservative or transient, calling Kimishima “the ideal successor to Mr. Iwata.”

And then he tells me a story about the Wii: “Think back to 2006, 2007. At this point the Wii had launched, and the huge issue that we were facing here in the Americas, was that there wasn’t nearly enough Nintendo DS as well as Wii inventory to satisfy demand here in the Americas,” he says. “These were the days of continuous shortages, lines around the block for the Wii at the Nintendo World store in New York City. Consumers weren’t happy, our retailers weren’t happy, and neither were we. So we devised a plan.”

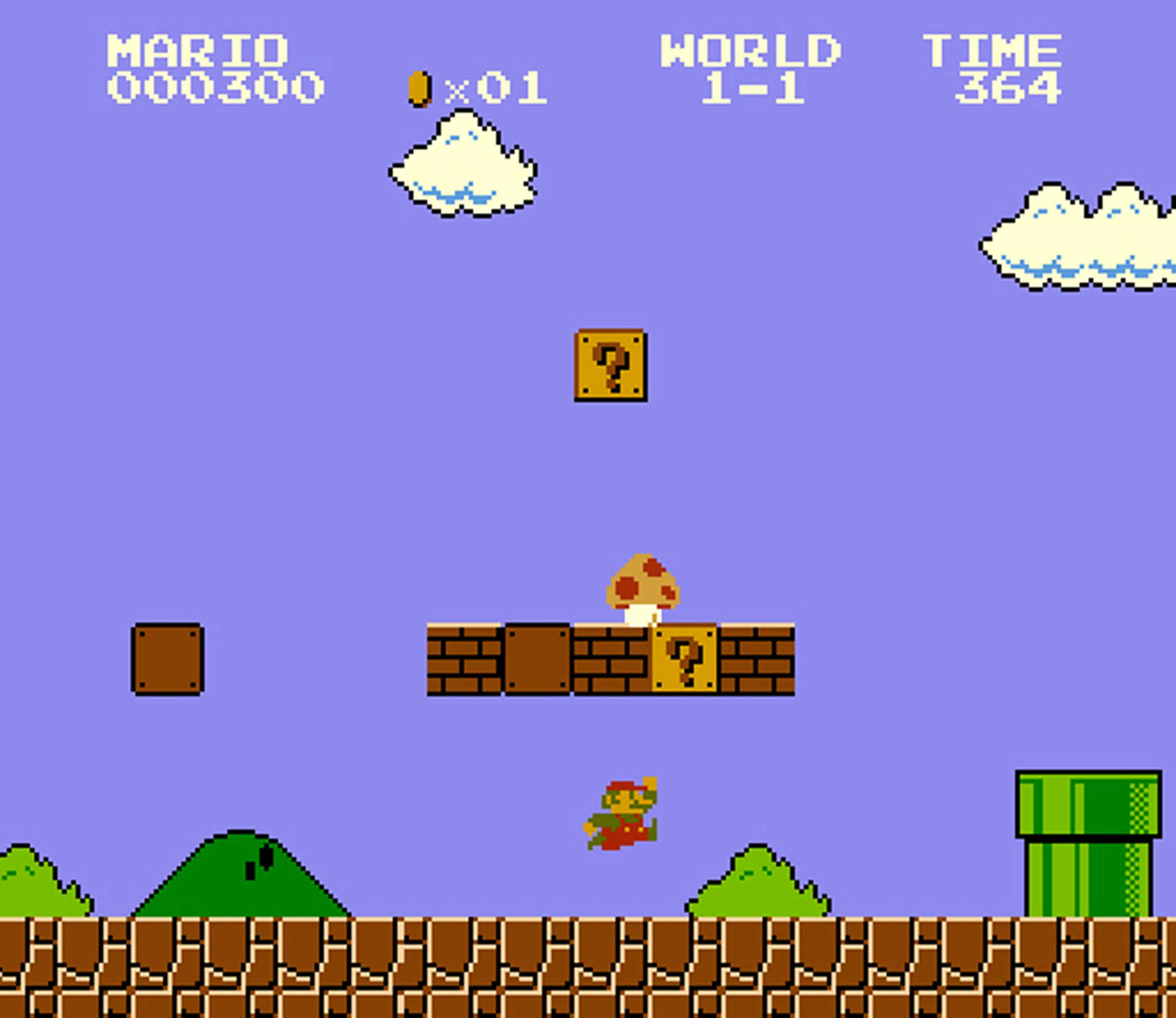

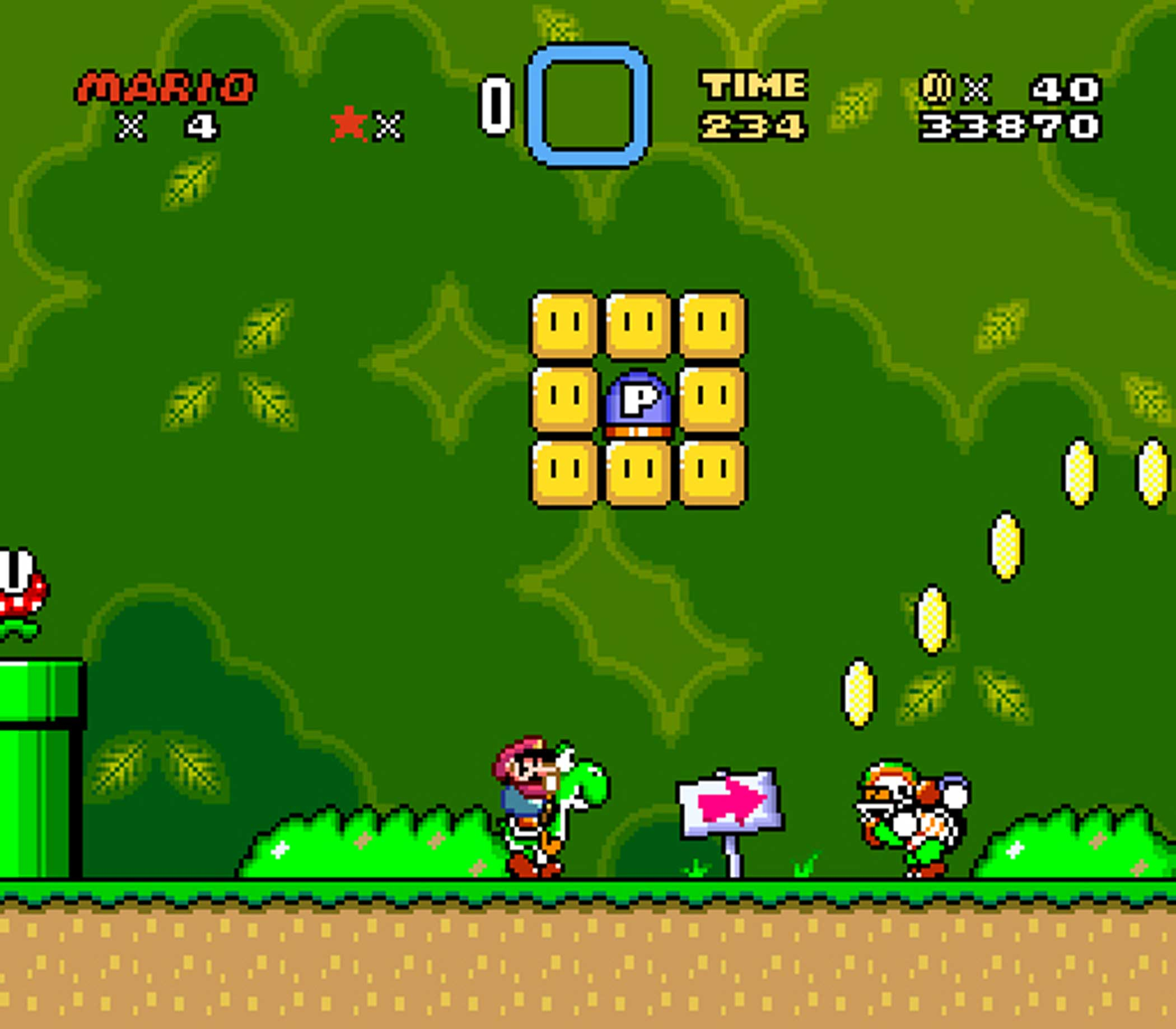

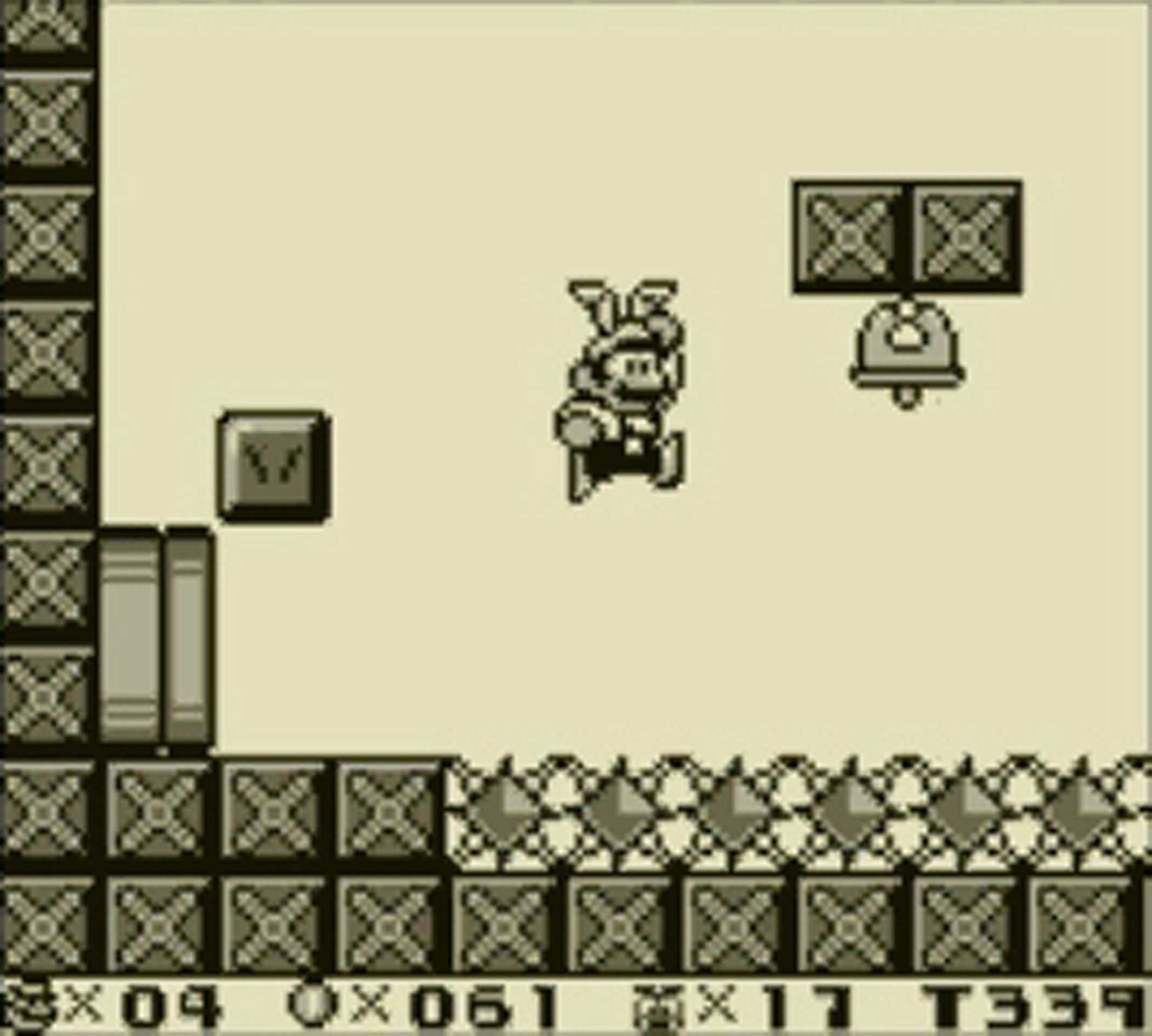

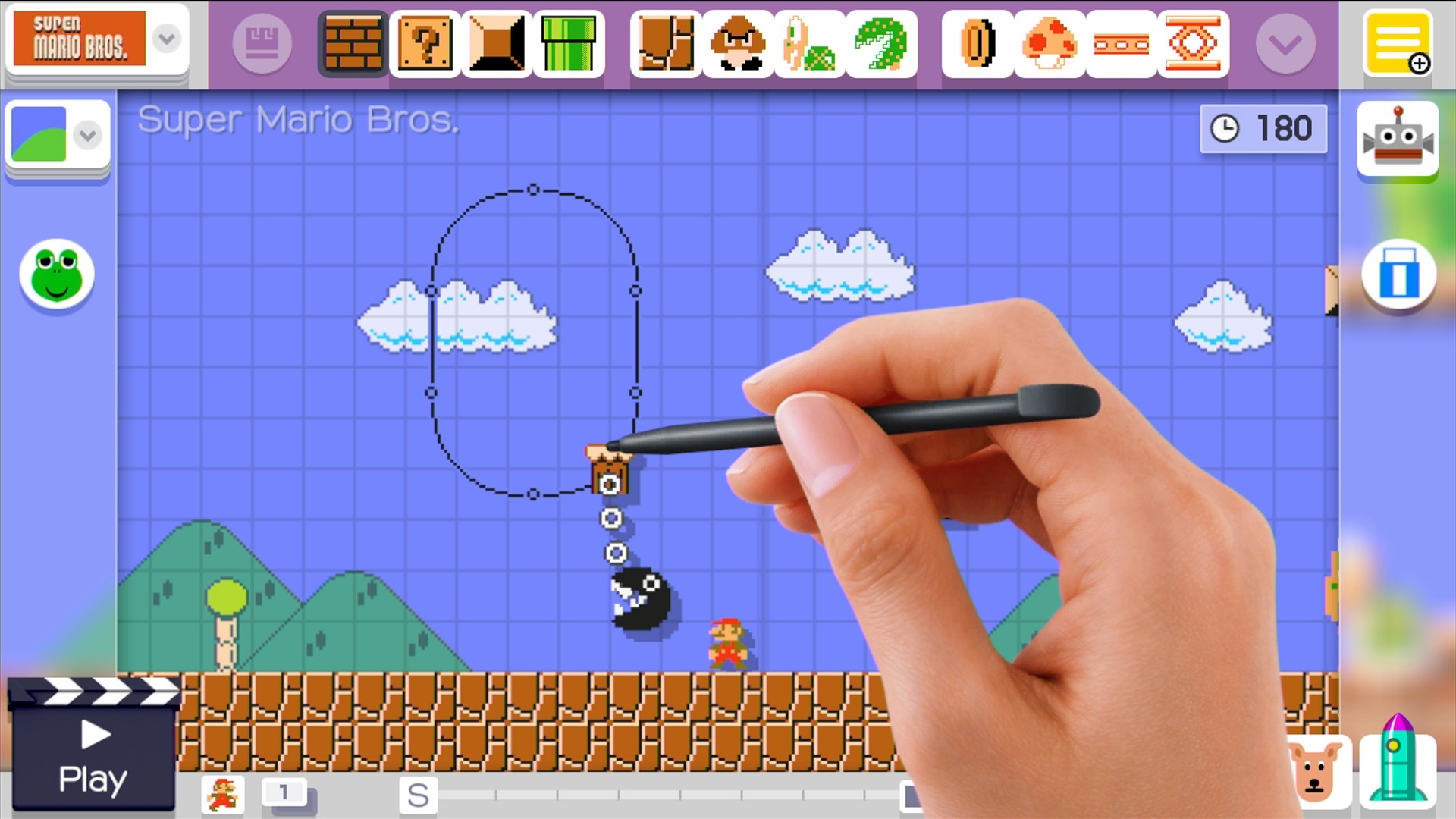

See How Super Mario Bros. Changed Over 30 Years

Enter Kimishima, the plan’s silent executor. “He began doing what he does, persuasively working behind the scenes to align global Nintendo organizations,” recalls Fils-Aimé, explaining how Kimishima orchestrated complex interactions between president Iwata, the company CFO, its head of manufacturing and “other key folks” at Nintendo corporate to fix the problems. As a result, the Wii returned to shelves in sufficient numbers to deliver record-breaking holiday sales in the Americas in 2008 and 2009. For its fiscal year ending March 2010 alone, which included most of 2009, the company’s net sales exceeded $15 billion.

“That is the way Mr. Kimishima works. He’s low profile, but very high efficiency,” says Fils-Aime. “And that’s what was recognized when in 2013 he was promoted to managing director for Nintendo globally and moved back to Japan.” Kimishima’s recollection of the story includes a telling moment where he says Iwata himself had significant doubts. “At one point even Mr. Iwata was saying, you know, he sort of whispered to me, ‘Mr. Kimishima, that’s impossible, that’s not a realistic goal.’ And I said ‘No, I think it is.’ And that’s again, saying it and repeating it and getting everyone onboard, that’s sort of the style that I adopted.'”

Kimishima faces similarly daunting challenges today. Except instead of grappling with too much demand for a hit product, the company must find a way to make consumers crave what it offers in an world dominated by tablets, smartphones, and free-to-play titles based on addicting feedback loops, not original characters and stories. What is surprising talking to Kimishima about these issues is how much our conversation reminds me of the one I had with Iwata this spring, when Nintendo unveiled its plans to develop experiences for mobile devices not made by Nintendo. There’s that same sense of speaking to someone who’s at once modest, playful, articulate and disarmingly candid.

“Most importantly I feel responsible for every single gamer."

When I ask him about his role as the hand behind the curtain during that holiday Wii shortage, for instance, his reaction is to downplay. “Success is not the result of individual efforts,” he says. “It is really the result of having good fortune, or having good luck. It’s not our place to go out and say ‘Hey, look at me, I did this, I was successful!'”

He’s equally upbeat about his ability to lead the company. “I feel that I have a firm understanding of this company,” he tells me. “I know how it operates. I know there are strings that can be leveraged, and that there are areas where improvement is required, and all this creates a great sense of responsibility. I feel responsible for every employee. I feel responsible for every shareholder. Perhaps most importantly I feel responsible for every single gamer.”

That responsibility will be tested in two ways next year. First: the introduction of Nintendo’s first title for mobile devices like smartphones. Dubbed Miitomo after the company’s cartoonish Mii characters, it’s intended to be a social networking app with artificial intelligence to get friends chatting. But despite a detailed slideshow released by the company explaining how it’s supposed to work, it was received with even more confusion. “I don’t think we have been able to successfully communicate what we’re trying to do [with Miitomo] at this point,” he says, responding to a question about whether he thinks Western consumers will “get” the product when it launches.

This is the difficulty Nintendo finds itself in: how does it stay true to itself while adapting to a much different kind of player on a much different set of devices. Even describing what it plans to do can be difficult. “Normally if you look at the smart device business, applications are not advertised, they’re not promoted, you just open up the app store and boom, there’s a whole bunch of new apps,” says Kimishima. “It’s just like, ‘Here they are!’, and they’re delivered to you. Taking time and money and effort to create large commercials around smart device applications has not been part of this business traditionally.”

Then there’s the mystery-shrouded NX, Nintendo’s next console. The company says it won’t even talk about it until next year. Kimishima says Nintendo has learned the lessons of the previous generation and won’t make the same mistakes. “I can assure you we’re not building the next version of Wii or Wii U,” he says. “[NX] is something unique and different. It’s something where we have to move away from those platforms in order to make it something that will appeal.”

And Kimishima says he plans to personally see the company through its upcoming endeavors and beyond. “I know that everyone is interested in how long I will be around,” he says, laughing. “I really want to say that all the initiatives I’ve discussed with you, these are on me, these are my responsibility and I have every intention of seeing these to fruition.”

“I can assure you we’re not building the next version of Wii or Wii U."

As we’re wrapping up, Kimishima tells me there’s one more thing Yamauchi taught him: the importance of staying within one’s means. “Or ‘Don’t try to be too big for your boots,'” he says, laughing once again and adding, “I have tried to keep this in mind in the management of Nintendo.” It’s a philosophy that already seems visible in Nintendo’s post-Iwata public engagements. Whereas Iwata personally helmed Nintendo’s periodic video updates to fans, Kimishima chose not to appear in the company’s mid-November presentation, it’s first following Iwata’s passing.

Instead, Kimishima seems poised be the public face of the company to its shareholders and financial community. That much observers suspected. But what many may have missed, is the deftness of the hand now turning Nintendo’s rudder. Kimishima hopes millions of fans will be eager to come along for the ride.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com