In the aftermath of the Paris ISIS attacks, the Oriental Pearl Tower in Shanghai lit up in blue, white and red, to mark the French tricolor. It was a heartfelt symbol in a metropolis that was once dubbed the Paris of the East — and the light display quickly provoked Chinese social-media chatter as to why similar memorials were not made when Muslim assailants slaughtered innocent Chinese over the past couple years. The most notable of those was a rampage at a train station in the southwestern Chinese city of Kunming last year, in which around 30 people were slashed to death by cleavers and others knives, and a bomb and car attack at a food market in the northwestern city of Urumqi, in which an equal number of civilians perished.

Soon after the Paris horror, China’s President Xi Jinping gave global import to the violence emanating from Xinjiang, a largely Muslim territory in northwestern China that has long chafed under Beijing’s rule. “China is also a victim of terrorism,” said Xi, blaming a group called the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) for unleashing terror in China.

Uighurs, a Turkic ethnicity native to Xinjiang, have long complained of repression at the hands of China’s ethnic Han majority. In the early 20th century, Uighurs proclaimed an independent republic called East Turkestan but, like Tibet to its south, the vast region was absorbed into the People’s Republic. Beijing maintains that Xinjiang — which is now China’s largest region by geography, rich in natural resources and still famed for its Silk Road history — was long part of the Chinese orbit. Still, in recent years, Uighur separatists have stepped up attacks on symbols of the state, such as police stations and military barracks. In a chilling escalation of bloodshed, militants have also massacred ordinary Chinese congregating in public places. Hundreds of people have been killed over the past couple of years.

But one reason for the understated public mourning for any Xinjiang-related violence is that news of attacks is often incomplete, delayed and politically fraught. Case in point: on Nov. 20, Tianshan Net, a state media organization that covers Xinjiang, published an online report detailing how an antiterrorist team spent 56 days tracking members of “violent mobs” who had slaughtered 11 people — many of them migrant Han coal miners — in the remote south Xinjiang region of Aksu. The Tianshan report said that paramilitary forces had killed 28 “terrorists,” as part of their manhunt. Yet no news of the actual Sept. 18 attack appeared in Chinese state media until two months after the bloodshed. How could people mourn something they knew nothing about?

The official blackout was punctured by the Uighur-language service of Radio Free Asia (RFA), a media outfit in Washington, D.C., that receives U.S. government funding and which has been accused by Beijing of fomenting separatist activity in Xinjiang. RFA initially reported that 50 people had died in the coal-mine attack. But little further information trickled out. Roadblocks in Aksu kept outsiders from the coal-mine area, especially curious foreign reporters.

On Nov. 24, Human Rights Watch urged that independent observers be allowed to investigate the Aksu raid. The day before, the People’s Liberation Army Daily, an official paper of the Chinese military, published an article that detailed how security forces deployed a flamethrower against suspected militants hiding in a cave before they were “completely annihilated.” Prior to Chinese official media publishing their accounts of the raid, RFA reported that children had been killed in the crackdown following the coal-mine attack. Telecommunications to the remote prefecture have been compromised in recent days.

Chinese security services are often discouraged from speaking to international media. Nevertheless, one Chinese policeman, who has been engaged in combat in southern Xinjiang, tells TIME that, post-Paris, he is concerned about copycat attacks in either Xinjiang or in large Chinese cities like Beijing or Shanghai. He describes the drumbeat of Xinjiang-related attacks as “already part of a global network of Islamic terrorism.” The policeman alleges that Uighur extremists have based themselves in Turkey, which has given refuge to exiles of fellow Turkic extraction.

“I’m worried that overseas Turkish terrorists will be inspired to wage similar attacks in China,” the policeman tells TIME. “They may guide domestic terrorists to initiate organized and well-devised attacks.” Turkey has denied that its citizens have provided training to Uighur militants.

Some foreign scholars who study the Uighurs have cast doubt on the notion that ETIM, the group singled out by President Xi, is orchestrating the string of attacks in China — even going so far as to dismiss the existence of ETIM as an operational unit. International academics have also questioned whether Uighur militants are truly part of a global jihadi network, instead recasting their violent campaign as an outgrowth of a localized struggle for autonomy (or separation) from the Chinese state.

For its part, Beijing points to the fact that a couple dozen Uighurs were locked up in Guantanamo by the Americans — after they were discovered in Afghanistan in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks — as evidence of Uighur complicity in a larger extremist movement. Someone using ETIM’s name did claim responsibility for bloodshed in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 2013, when an SUV careened through the crowds killing five people, including the three Uighur occupants of the vehicle. There have been few reports, outside of Chinese state media, however, of Uighurs joining ISIS.

Still, there’s no question that Uighurs have carried out bloody attacks on innocent people in China — and that the Chinese police are on the front lines of a little publicized crusade. The September Aksu attack, for instance, claimed the lives of five policemen, yet their deaths went unmarked by Chinese state media for two months.

“If you have never been in the battlefield, how can you understand how cruel the enemies are?” says police officer Sun Kai, who was stationed in Xinjiang for 12 years. Sun is from China’s Han ethnic majority but some of his fellow officers were Uighur. Last April, Sun recalled on a Chinese social-media site, he was awoken just before midnight by a pair of gunshots. Rushing outside, he saw “one of our Uighur comrades laying on the ground, his whole body covered by blood.” The Uighur officer had been stabbed five times by “terrorists,” according to Sun, who rushed his colleague to the hospital. The Uighur policeman “whispered ‘I want to call my mom. If I cannot go home, please tell her I hope she lives happily in the future.’”

Sun’s comrade survived. But the experience, along with many other clashes with suspected militants, left Sun determined to defend his role in Xinjiang to TIME. (Earlier this year, he was transferred to the southern province of Guangdong.) “Because I’m a policeman I will combat [the militants] relentlessly,” he wrote on social media. “I have two characters for these terrorists: xiao mie.” Together, the Chinese characters mean annihilation.

Aksu, where Sun was stationed, was once famed for its melons, carpets and resplendent mosques. It is now a bristling military zone where repeat attacks have left both Uighurs and Han on edge. In parts of Xinjiang, Muslims are encouraged by the state to avoid physical markers of their religiosity, such as veils or beards. On occasion, Uighur government workers have been banned from fasting during Ramadan and male Uighur college students barred from mosques. Even before the latest escalation of violence, racial tensions have exploded. In 2009, rioting between Han and Uighurs killed hundreds in the regional capital of Urumqi. Waves of Han migration have also shifted the ethnic balance in what is officially known as the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. (Xinjiang means new dominion or new frontier in Mandarin.)

The voices of Chinese police on this troubled frontier are rarely heard. Theirs is not part of a triumphal Chinese narrative in which various ethnicities, from Tibetans to Uighurs, coexist harmoniously. But with the Paris attacks, images and reports of Chinese paramilitaries have cropped up in local papers and even on the Ministry of Public Security’s social-media feed. At the same time, several Han policemen in Xinjiang have taken to Chinese social-media services to express themselves, despite the state occasionally shutting down their accounts. Officer Sun wrote this summer that “for some terrorists, armed force is not a deterrent because these terrorists have been brainwashed and they do not fear death.” The only solution, Sun wrote, was a long-term one: education. “We should ensure a pure education environment and stop the spread of radical ideas among students,” he wrote. “Twenty years of persistent education will change a people’s values, and then eliminate the roots of terrorists.”

Another policeman has taken the online moniker “Anti-Terrorist on the Frontier.” He would not discuss the specifics of his job with TIME but admits to the stress of his job. “Our work is very demanding and we work under huge pressure,” he tells TIME. “We almost work everyday without rest, we have no weekends, eight hours per day.” The policeman is clear about whom he thinks is fomenting conflict between Uighurs and Han. “Religious radicals and separatists are trying to alienate the Uighur from the Han people,” he says. “Some foreign forces, such as the Turkish and American democracy foundations, are also supporting the radicals and separatists.”

Other members of China’s security force relieve stress in more unusual ways. Yan Yuli is a 20-year-old patrol policeman from the fabled oasis town of Kashgar. An ethnic Han, he relaxes through the unusual pastime of finger-dancing. Last year, he took part in local TV talent competitions, wiggling his fingers to a hip-hop beat. “No matter what kind of job you are doing,” he wrote in July on his social-media account, “how stressful your job may be, never give up.”

Dilireba, who is from the Tajik minority that also lives in Xinjiang — the autonomous region borders eight countries, including Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Russia — blows off steam by posting pictures of kittens and puppies on Weibo. In that, she is no different from millions of other people on social media. But Dilireba also posts pictures of herself in a snowstorm, wearing her special-forces uniform and brandishing a machine gun. On Aug. 1, she noted that the date was the anniversary of the founding of China’s People’s Liberation Army. “Happy holiday,” she wrote, “to my combat companions working on the front lines.”

— With reporting by Gu Yongqiang / Beijing

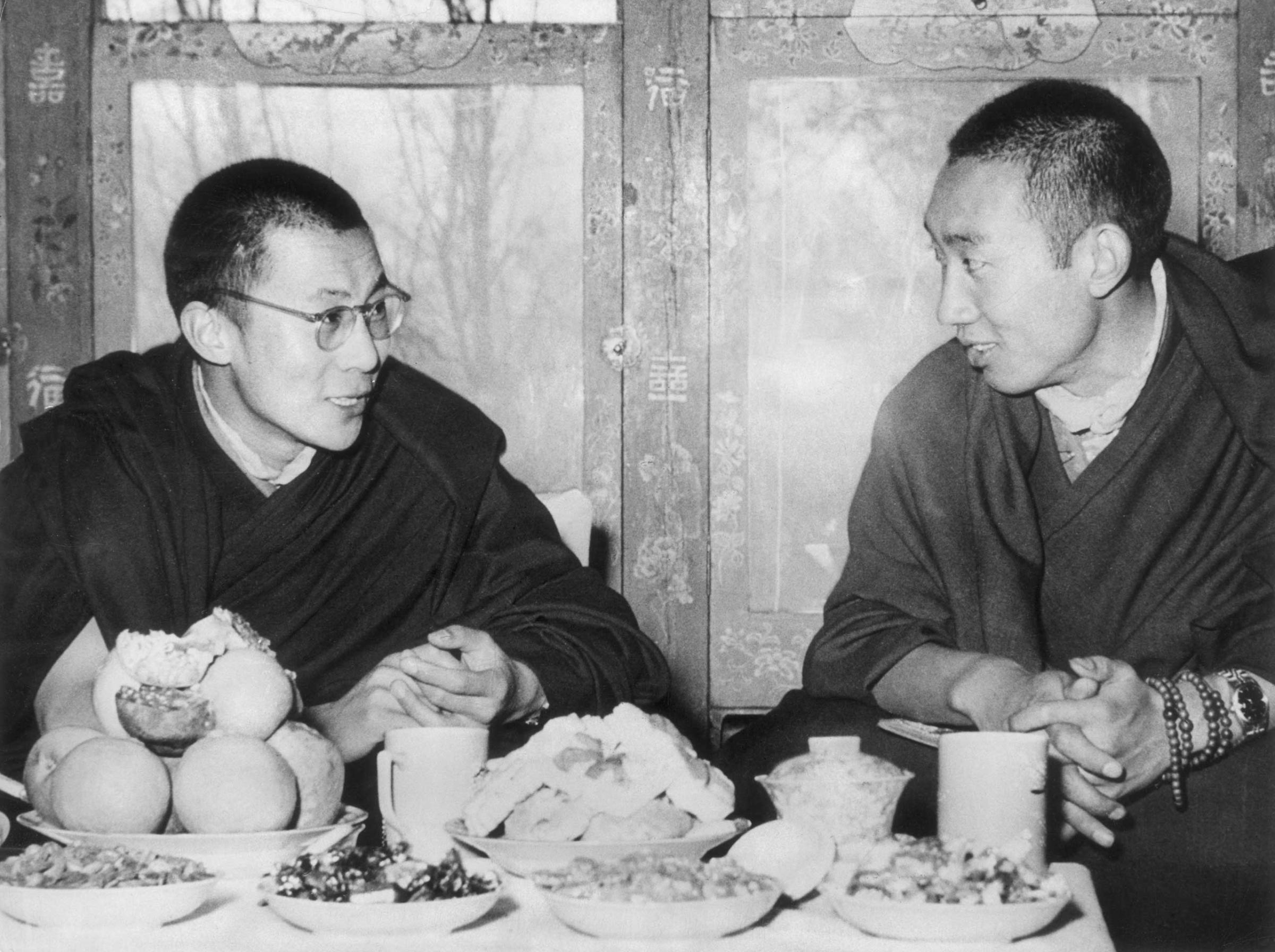

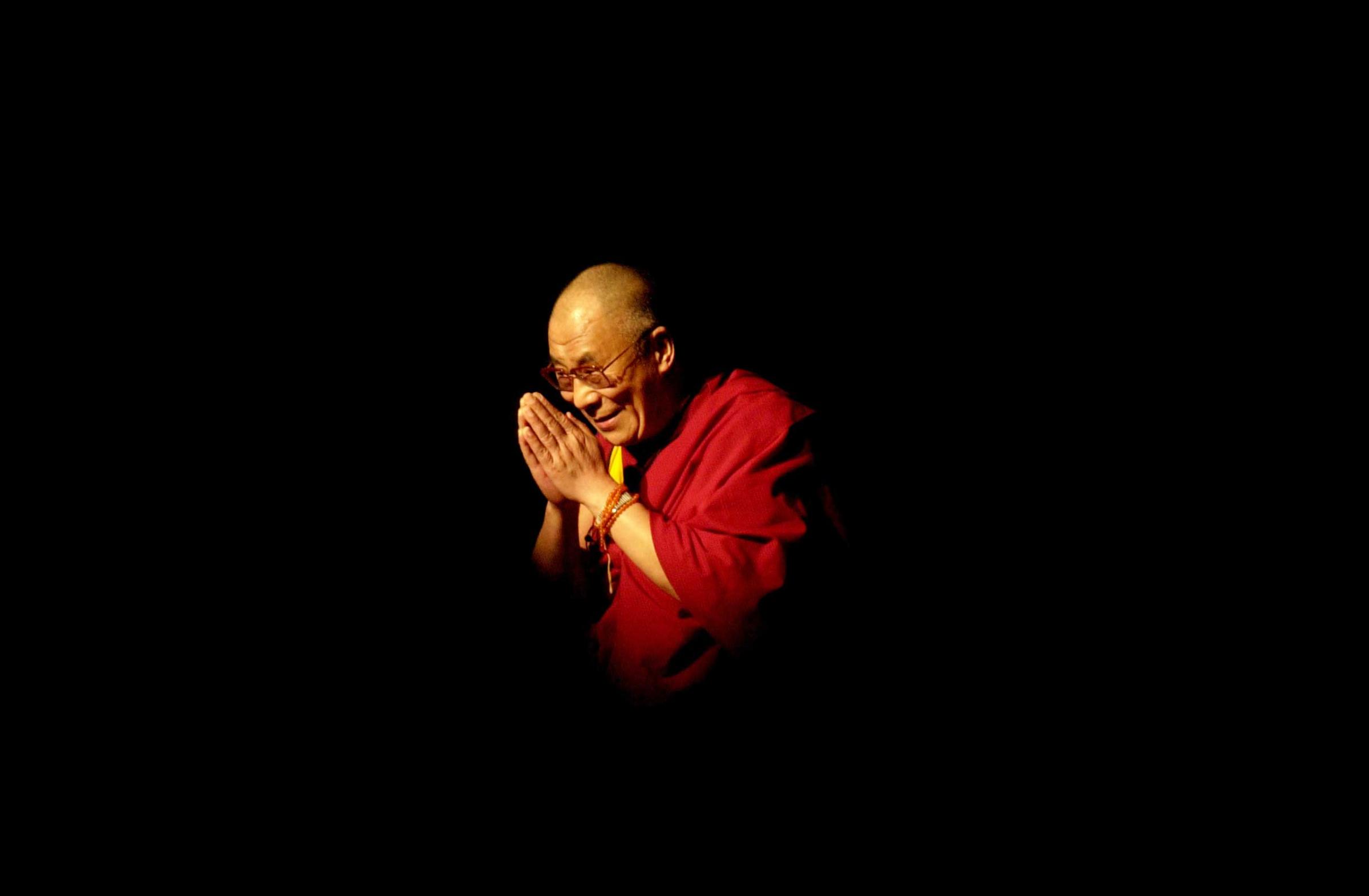

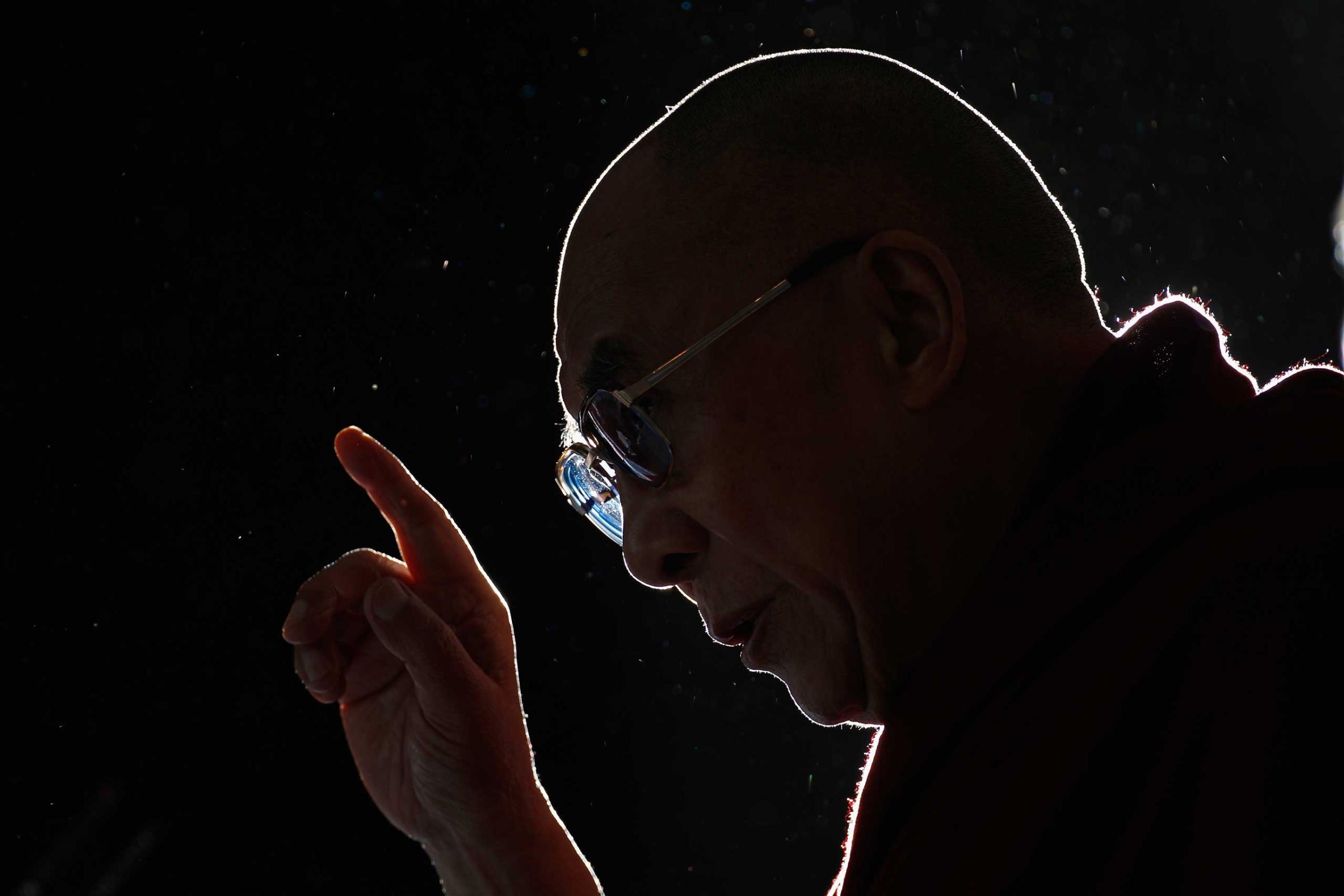

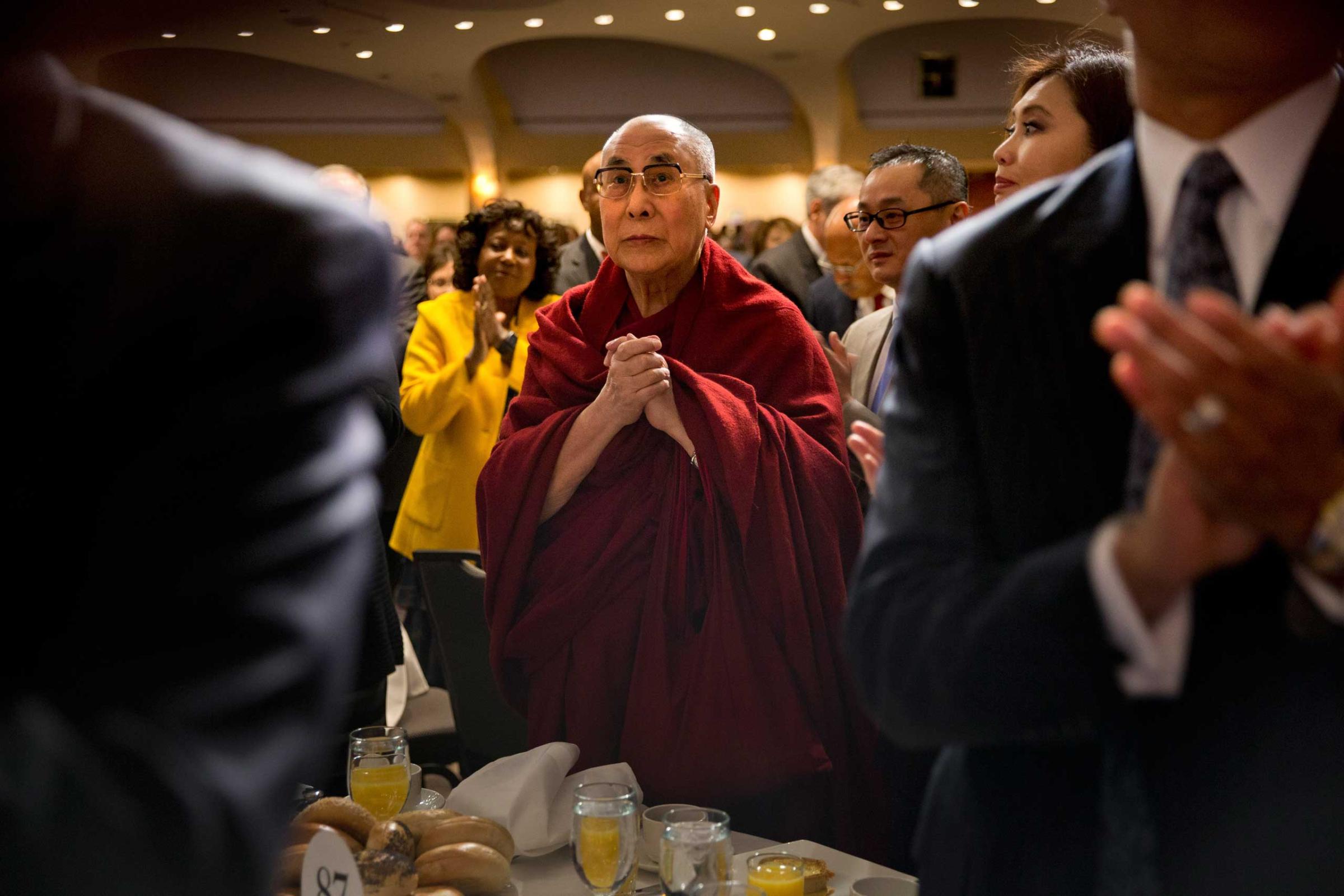

See the Dalai Lama's Life in Pictures

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com