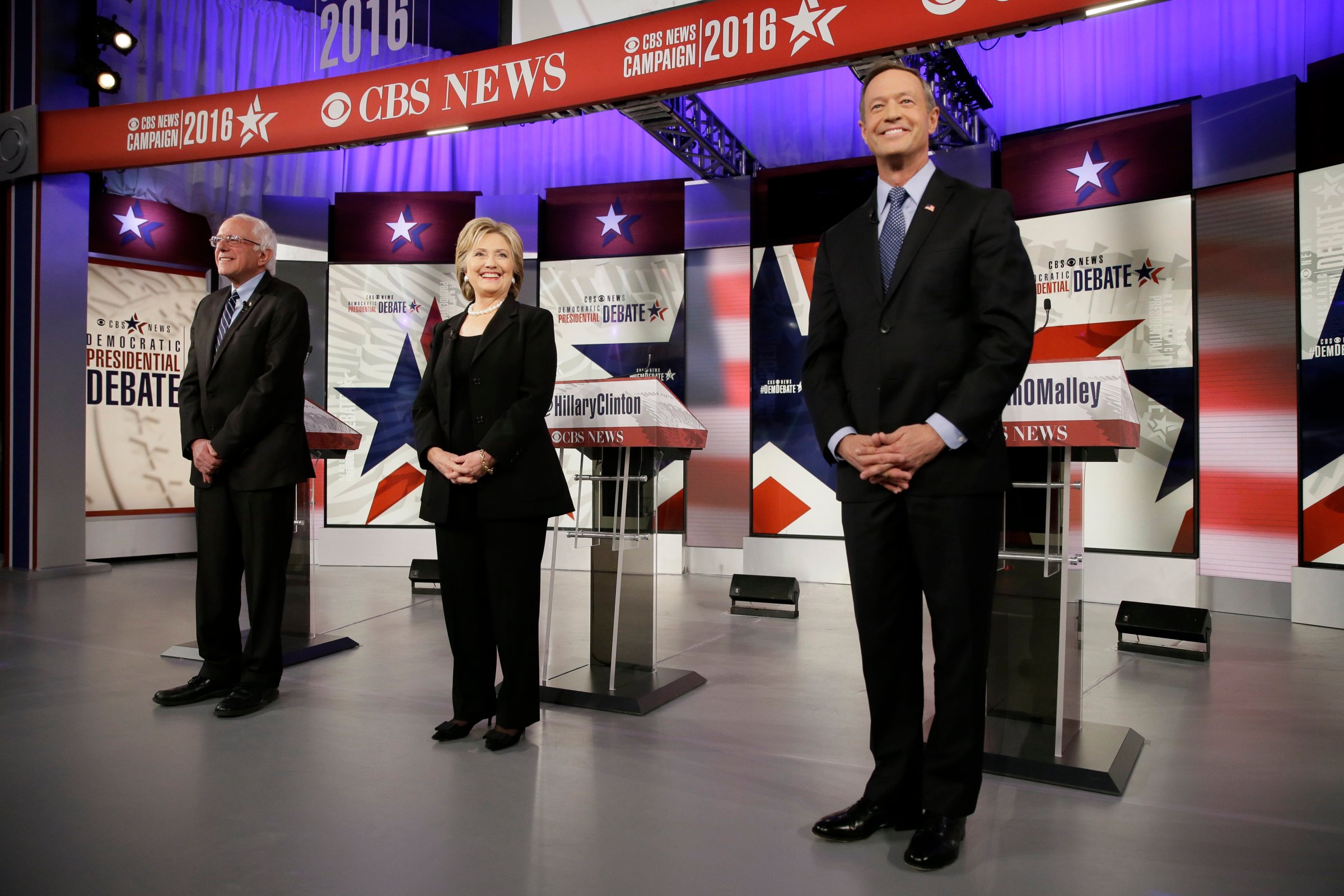

On the night after the Paris-terrorist rampage, three Democratic presidential hopefuls debated in Iowa and proclaimed that they were very, very concerned about the attacks and the growing evidence that ISIS—or Daesh, as it is called in the region—has metastasized into a true global threat. Very concerned. Senator Bernie Sanders thought that this barbaric challenge to civilization should be “eliminated” … although, he later allowed, Daesh was not as great a threat as global warming, which—hold on, here—causes terrorism. You know, droughts and floods set people in motion and … well, never mind.

Sanders’ lack of proportion on this issue—and yes, climate change is a problem, but not the immediate threat to our security that Islamic terrorism is—was, sadly, typical of what passed for post-Paris political discourse among Democrats and Republicans alike. Both parties were handcuffed by less than relevant impulses inflicted on them by their extremes. For Democrats, it was the solipsistic insistence on political correctness, which makes it near -impossible for liberals to face, head on, by name, the essential problem: the rise of Islamic radicalism. For Republicans, it was the half-crazed nativism of the far right. Their candidates quickly worked themselves into a demagogic lather about whether or not we should be accepting Syrian refugees, a sub-sidiary question at best, which crowded the real issue—what to do about Daesh—out of the debate. Senator Lindsey Graham, the presidential candidate who has been trying hardest to think through a military response to the problem (but is currently polling below the waterline), said his colleagues were “taking the coward’s way out,” through “red-hot, red-herring politics.”

Of the Democrats, Hillary Clinton came closest to describing what the crisis is and who the enemies are, but she was rendered incoherent by politically correct subterfuge. She wouldn’t say the words “Islamic radicalism” but proposed instead that our foe is “Jihadism.” Jihad is, of course, an Islamic principle associated with religiously inspired aggression. There are no Eskimo Jihadis.

Why is it so important to call Islamic radicalism by its proper name? Because it’s not just a word game. There is a crisis within Islam, an ideological struggle caused by the rise of Wahhabi-style fundamentalism over the past century. If we acknowledge the true nature of this battle, it becomes easier for us to identify our friends and enemies, especially the latter. Our enemies are those who have funded and promulgated -Wahhabi-style Islam through radical madrasahs in the Islamic world. It starts with Saudi Arabia, whose tottering monarchy made a devil’s bargain with local Wahhabi clerics decades ago. The Saudis seem far more concerned with Shi‘ite Iran than with the Sunni extremists of Daesh. In recent weeks, they and their Gulf allies have turned their attention away from Daesh and focused on the Shi‘ite rebels in Yemen, who represent a far less potent threat to global stability. And yet neither Saudi Arabia nor its radical, proselytizing strand of Islam was mentioned by the Democrats in the Iowa debate.

But then nothing much was—other than a general belief that America should lead the fight against ISIS in consultation with our allies within and outside the region. Which is what we have been doing, to some effect, but not enough.

The big question—unasked and unanswered by the Democrats—is whether the recent evidence of global reach by ISIS requires a change in U.S./NATO strategy. It is possible that some of France’s European neighbors are, finally, ready to take more robust military action. An alliance with Russia is no longer unthinkable. The central issue in the weeks to come will be, Can we build a military coalition—like the supple one built by George H.W. Bush in the Gulf War—to take on the limited mission of destroying Daesh’s safe havens without occupying them?

It is a vexing, toxic question given our recent history of military failure and carelessness in the region. Few politicians in either party are willing to address it directly. The two leading Republican candidates—Dr. Ben Carson and Donald Trump—have been laughable in their attempts. Of the rest, Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush seem to understand the complexity and crosscurrents of the situation, although they have yet to produce coherent plans. Graham, and his call for 10,000 more troops on the ground, seemed quixotic at best—before Paris. His credibility remains limited by his proximity to Senator John McCain, who has favored intervention—just about everywhere.

But Graham understands some basic pieces of the puzzle: Syria’s President, Bashar Assad, can’t go, for the moment. The immediate enemy is Daesh. “ISIS is Germany and Assad Japan,” he says, using a World War II reference. Graham also understands that Egypt and Jordan are the two Sunni armies most likely to join the fight. The problem, as always, is what do we do after the Daesh safe havens are captured? Graham uses the rhetoric of the last Iraq war, “After we clear, we hold and build.” For how long? The very words strike fear among those of us who remember what happened last time around. But at least Graham is trying to think this through. Other Republicans, like Ted Cruz, are using the crisis to make a cheesy political appeal to evangelicals: Only Christian refugees should be accepted from Syria.

As for the Democrats, one wonders how Sanders and the civil liberties left now feel about drone strikes and the aggressive collection of terrorism–related data.

Obviously, there are no simple answers to Islamic terrorism. There aren’t even any difficult answers. It is an unsolved puzzle, a massive conundrum. The use of military force has been counterproductive, but the absence of a forceful response dooms us to a potential loss of fundamental freedoms, a life lived without heavy-metal concerts and soccer matches and trips to the mall. President Obama’s sad response to Paris—that nothing more can be done than what he is doing—was deflating. Perhaps there are plans afoot that he cannot share. But it seems clear there are few people running for President in 2016 who are even asking the right questions, much less providing possible answers to the most threatening problem of our age. •

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com