This post is in collaboration with The John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress, which brings together scholars and researchers from around the world to use the Library’s rich collections. The article below was originally published on the Kluge Center blog with the title The Civil War, Reconstruction and the Transformation of African American Life in the 19th Century.

This year the nation commemorated the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War. The war was a period of great transformation in America, in Washington, D.C., and in the lives of African Americans. Those changes continued into the second half of the 19th century. Jason Steinhauer sat down with historian Kate Masur, a former Kluge Fellow at the Kluge Center and a recent returnee to the Center for this past year’s #ScholarFest, to discuss.

Hi, Kate. Thanks for joining me. Let’s jump right into it: your work examines the Civil War and Reconstruction era in Washington, D.C., and you’ve stated that this was a period of great transformation in Washington. Could you broadly identify some of those transformations?

There were two lasting transformations: the city’s growth and the abolition of slavery. Abolitionists had been trying for decades to persuade Congress to abolish slavery in D.C., but Congress – dominated by slaveholding interests – would not move. Thus when Congress finally passed an abolition act for the capital in April 1862, it was clear that changes of vast magnitude, for the city, the region, and the nation as a whole, were at hand. At the same time, the war brought thousands of new people into what had been a relatively small city. Many of them were transient and left when the war machine disbanded; overall, however, population growth continued, a real estate boom ensued, and Washington began to become the modern city we know today.

What were conditions like for African Americans in Washington at the start of the Civil War, and how had those changed by war’s end?

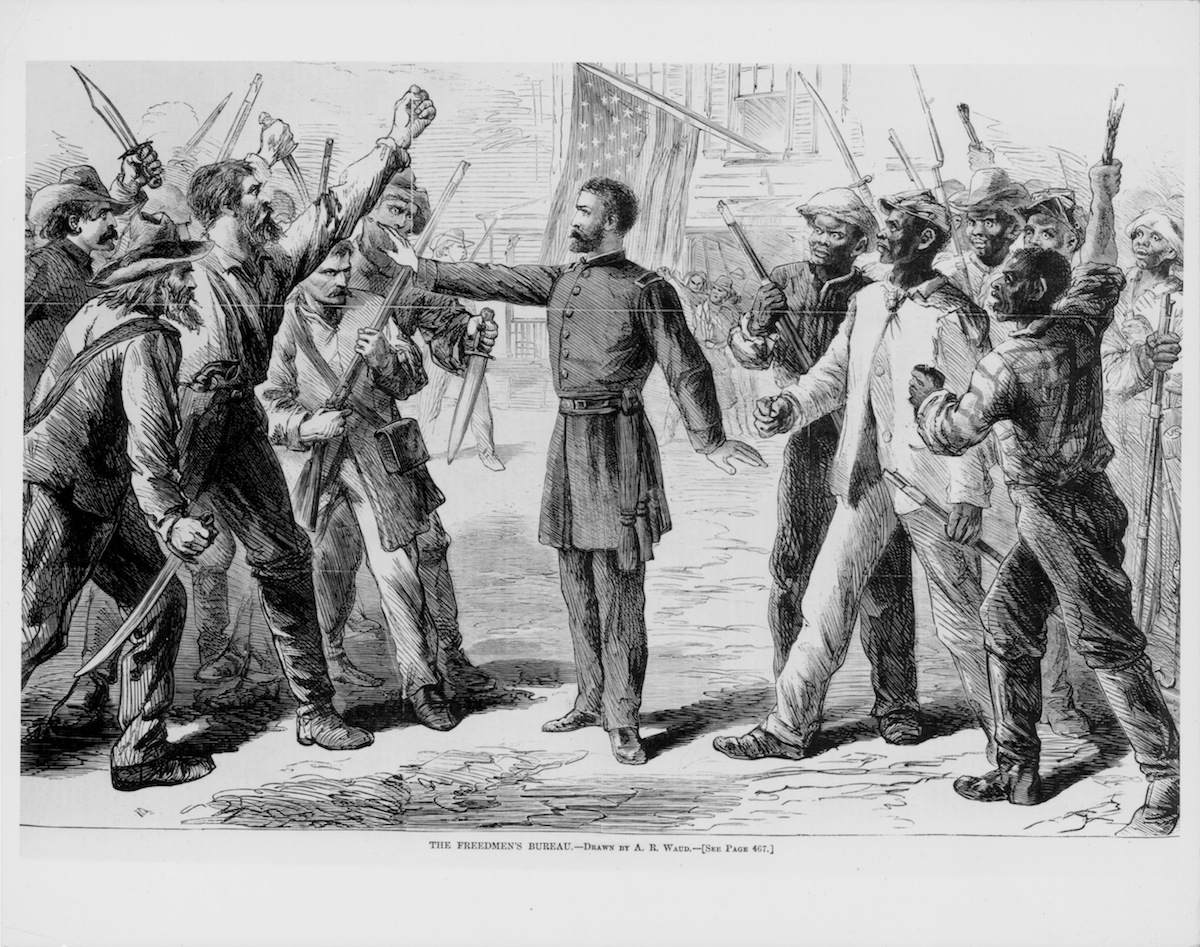

As the war began, not only was slavery legal in the District of Columbia, but racially discriminatory “black codes” impinged in the lives of free African Americans, forcing them to carry passes, stay inside at night, and pay unfair licensing fees work in certain businesses. The threat of sale into the interstate slave trade hung over all African Americans in the region, enslaved and free. By the end of the war, slavery had been outlawed not just in D.C. but nationwide, African American men had served with valor in the United States army and navy, and black organizations had come out into the open, playing visible roles in the city’s civic life. Schools for African Americans flourished under auspices of local educators, outside missionaries, and the Freedmen’s Bureau. And the population itself was transformed by the migration into the city of thousands of former slaves from the surrounding countryside. The migrants faced shortages of housing and employment, so this was also a difficult period for the many people who were buffeted by disruptive forces they could not control.

Was D.C. a catalyst for the shift in national attitude on Emancipation during the Civil War – or did D.C. follow the lead of others?

African Americans’ political mobilization in Civil War Era Washington was both sophisticated and effective. During the war, northern black leaders began to come to Washington, joining a black population that had been disproportionately free before the war and had fostered numerous strong organizations, including churches and private schools. People realized that in Washington they had the ear of members of Congress, especially those who emerged from the anti-slavery movement. African Americans attended congressional debates in growing numbers, starting during the war. Henry Highland Garnet, an activist and minister who had spent most of his time in New York, became pastor of the city’s prominent and prestigious 15th Street Presbyterian Church and, in February 1865, became the first African American to give an address in the chamber of the House of Representatives, when he delivered a speech in honor of the House’s recent passage of the 13th Amendment. George T. Downing, a caterer and civil rights activist from Rhode Island, managed the restaurant in the House of Representatives and used it as a platform for lobbying members of Congress. In short, Washington, D.C., became a national hub for black political life, and the impact was evident not just in the Capitol but on the streets of the city itself.

The period following the war is known as Reconstruction Era, and as you and other historians have noted it is an era that remains controversial. What about it has remained so contentious?

In the years following the Civil War, Americans had no choice but to grapple with questions about race, rights, and power that remain contentious to this day. The immediate problems were how to bring the former Confederate states back into the Union and how to secure the freedom of former slaves. But these very specific dilemmas were in fact subsets of much broader questions: What rights were all persons in the United States entitled to, and what government entity would guarantee those rights? Who is an American citizen and what are the rights and obligations of citizens? What is the relative power of the federal government in relation to state and local governments? It is difficult to talk about Reconstruction without invoking these rather fraught questions, but in my view that is precisely why we should talk about Reconstruction: because the period forces us to grapple with incredibly important issues that continue to resonate in the present.

Read the rest of this interview here at the blog of the John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress

Kate Masur was a Kluge Fellow in 2004 and is currently an Associate Professor of History at Northwestern University. Parts of her book “An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, D.C.” were researched at the Kluge Center.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in Februar

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com