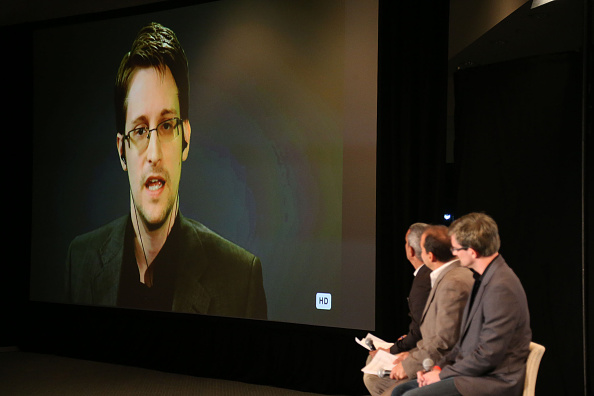

Three days after the horrific attacks in Paris, the memory of Edward Snowden looms large in American politics.

How did the intelligence community fail to intercept news of these attacks? How did eight terrorists manage to communicate not only with one another, but allegedly with accomplices in the region and with I.S.I.S. leaders in Syria, without attracting the attention of counterterrorism agencies in Europe and the U.S.? More to the point: With more surveillance and fewer privacy protections, is it possible that Friday’s attacks could have been stopped before they began?

It is, of course, an infuriatingly hypothetical question—the stuff of sci-fi crime procedurals—but by Monday, it had sparked a major debate in Washington. Current and former U.S. officials from both the Obama and Bush administrations mostly argued that the Paris attacks illustrate how privacy concerns in the wake of the Snowden leaks went too far, while privacy and civil rights advocates frantically pumped the brakes.

There are two main questions at issue. The first is whether, and how, government intelligence agencies, such as the National Security Agency and the Central Intelligence Agency and their brethren in Europe, should go about monitoring the phone calls, text messages and Internet communications of suspected criminals or the public at large.

The second is what to do about encryption. A recent bill, which did not pass Congress, would have forced big tech companies in Silicon Valley and elsewhere to engineer into their products “backdoor” keys that could be used by law enforcement officials to get a warrant to unlock encrypted conversations. As it is, many popular texting services, including Apple’s iMessenger and Yahoo!’s nearly ubiquitous WhatsApp, use what’s known as “end-to-end” encryption, to prevent data from being read as it passes through the Internet.

Kevin Bankston, the director of the Open Technology Institute at New America, was careful to point out that there is currently no evidence suggesting that the terrorists in Paris used encrypted applications in the first place.

“But even if it’s true, it adds more heat than light to the crypto debate,” he explained to TIME. “Regardless of whether they did or didn’t use encryption, the simple fact is that trying to ban or backdoor strong encryption just won’t work.” One problem is that outlawing the use of encryption won’t stop terrorists from simply engineering their own encryption algorithms. Another is that while forcing companies to fashion “backdoors” into their products makes it easier for intelligence agencies to gather information, it also makes it easier for criminals, stalkers, or even terrorists, to snoop on private conversations.

“You don’t necessarily want to do something that helps a terrorist know exactly if the [French president] Hollande just let his family know he’s on his way home,” said the head of a large private cybersecurity firm, who asked not to be named because of the political nature of the question.

Meanwhile, many current and former intelligence officials seemed to suggest that privacy concerns have gone too far.

CIA director John Brennan suggested that the public’s reaction to the NSA mass data-collection program, which was revealed by Snowden in 2013, has had the effect of dismantling intelligence capabilities. “In the past several years, because of a number of unauthorized disclosures and a lot of hand-wringing over the government’s role in the effort to try to uncover these terrorists, there has been some policy and legal and other actions taken that make our ability, collectively—internationally—to find these terrorists much more challenging,” Brennan said at a Center for Strategic and International Studies event Monday. “And I do hope this will be a wake up call, particularly in some areas in Europe, where I think there has been a misrepresentation of what the intelligence and security services are doing by some quarters that are designed to undercut those capabilities.”

Read More: Read the CIA Director’s Thoughts on the Paris Attacks

President George W. Bush’s former press secretary and current Fox News commentator, Dana Perino, blame Snowden more overtly. “F Snowden. F him to you know where and back,” she wrote in a tweet on Friday as news of the bloodshed unfolded.

Michael Morell, President Obama’s former deputy CIA director and current CBS News senior national security commentator, pointed the finger at the problem of encryption. It’s a real issue, he said, that terrorists are able to “communicate under the radar” by using encrypted messages “that we can’t break,” he said on CBS Monday. “I think this is going to open an entire new debate about security versus privacy,” he added. “We have, in a sense, had a public debate. That debate was defined by Edward Snowden…and the concern about privacy. I think we’re now going to have another debate about that. It’s going to be defined by what happened in Paris.”

Read More: Former CIA Director: ISIS Will Strike America

On MSNBC, California Sen. Dianne Feinstein pushed some blame on big tech companies too. “I think Silicon Valley has to take a look at their products,” she said. “If you create a product that allows evil monsters to operate in this way … That is a big problem.”

Stewart Baker, who served as a former counsel of the National Security Agency under Bill Clinton and as an assistant director of policy for the Department of Homeland Security under George W. Bush, took a measured position. The privacy advocates’ argument that “backdoor” encryption won’t work isn’t exactly right, he told TIME. Companies make decisions all the time as to how much privacy and convenience they afford their customers; a law requiring a company to engineer a backdoor for intelligence officials would be along that same continuum, he argued.

The big Silicon Valley firms’ insistence that “it cannot be done” should be understood in the same way that energy companies balk at new regulations on global warming or air pollution: they don’t want to do it, “but where is their social responsibility?” he said. “It is hard, and there will never be a complete solution, but pretending that you’re not a part of the society that raised you—the way that Silicon Valley has tried to do—is not constructive.”

The question of how much privacy or how many civil liberties citizens are willing to exchange for safety and security has, of course, haunted the country since well before 9/11. But in recent years, particularly in the wake of the Snowden leaks, the pendulum seemed to have swung toward privacy.

Earlier this year, members of Congress, in response to an outpouring of public support, overwhelming voted in favor of an amendment banning requirements that companies “backdoor” encryptions. Powerful tech firms, like Google and Facebook, along with the grassroots advocacy of “netizens,” make the passage of any new anti-encryption laws an uphill battle, if not impossible. But should anything like what happened in Paris last week occur on U.S. soil, all bets are off—a scenario that privacy advocates caution against.

“In the end, we can hurt ourselves much more than the terrorists can hurt us,” Bankston of OTI wrote. “Indeed, that’s their entire strategy.”

Read Next: CIA Director Says ISIS Likely Has Other Attacks Planned

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Haley Sweetland Edwards at haley.edwards@time.com