The street that Omar Ismail Mostefai grew up on was like any middle class neighborhood across France. The two-story cream houses in the development curve into tiny cul-de-sacs, providing ideal lanes for children like Mostefai and his two brothers to play soccer. This is a neighborhood of taxi drivers, utility workers and accountants. Or, in Mostefai’s case, a bakery assistant.

How Mostefai went from a hipster teenager in Chartres, about 80 miles southwest of Paris, to suicide terrorist is beyond anyone who knew him in this bucolic hamlet at the mouth of the famous Loire Valley. Mostefai, thus far the only assailant identified in the Paris terror attacks, lived here from at least 2004 to 2012 with his parents, two brothers and two sisters. Neighbors say the 29-year-old married here and had a baby daughter before moving away.

“They were a beautiful family,” says a neighbor of Moroccan descent who moved across the street in 2005 and wished to remain nameless for fear of radical reprisals. “Omar, as we called him, was a normal guy in sneakers and baggy pants. He had long hair and a thin, hip beard.” In the street in front of Mostefai’s former house here on Sunday white, black and Arab boys all played soccer together.

Mostefai was more of a delinquent in his Chartres years, arrested eight times for infractions like driving without a license, but never imprisoned. “This was not a guy who was going to take a Kalashnikov and kill a bunch of people,” the neighbor says, recalling Mostefai’s goofy smile and easy-going nature.

The family was Muslim enough for the women to cover their heads and not work, says another neighbor, but not so Muslim that the women wore burkas and walked three steps behind their husbands, like some other families in the neighborhood. Mostefai and his father—but no one else in the family—attended a mosque up the street, Anoussia, but “Omar was timid, gentle. There was no radicalization in him,” says Ben Bammou, the mosque’s president. “We are devastated. We pray for the victims and their families.” He fears that their mosque will now come under more scrutiny and surveillance. “We were already stigmatized before this.”

It is partly that stigmatization that drove Mostefai, who was of Algerian descent, to extremism, argues Myriam Benraad, a research fellow specializing in Iraq and the Middle East at the Foundation for Strategic Research in Paris. “ISIS promises to avenge all the injuries of colonialism, the Iraq wars; all the injures of the past. ISIS is a myth, but it’s one that they stick to versus other myth—the French dream, as it were—that they see as unfair and oppressive,” says Benraad, who wrote her dissertation on the imam who radicalized the Kouachi brothers, who helped carry out the Charlie Hebdo attacks in January. “These guys never felt fully French, especially Algerians, or the children of Algerians. To them, the memory of [France’s occupation and war in Algeria] is always here. It’s profound. It’s an injury that the children of immigrants have been living with their whole life, while also facing discrimination.”

Unlike the Kouachis, who didn’t speak Arabic and felt that as wards of the state—their parents died when they were young—that their culture had been robbed from them, Mostefai had a strong family infrastructure before he was radicalized, reportedly by a Belgian-born itinerate imam in 2010. But even with that support, Mostefai was susceptible to the lure of ISIS, a group that notably during the Baltimore riots put out an appeal to African Americans, promising a post-racial society in the supposed post-colonial utopia they were creating in Syria and Iraq. Investigators say he spent time in Syria between crossing into Turkey in the fall of 2013 and returning to France in the spring of 2014.

Mostefai is hardly alone— some 600 of young French men are suspected to be in touch with ISIS and 185 of whom have actually traveled to Syria or Iraq and back. “Most of the plots that we’ve uncovered—10 in France and five since January—were conceived by sympathizers,” says Jean-Charles Brisard, a Paris-based terrorism and security expert.

While the Kouachi and Mostefai generation has never experienced colonialism the way their parents or grandparents did in Algeria, they see the U.S. invasion of Iraq as neo-colonialism and the U.S., France and the U.K.’s involvement in Syria as another example of racially-driven oppression. The Kouachis were allegedly radicalized after the Abu Ghraib prison scandal; one of Mostefai’s co-attackers allegedly blamed French President Francois Hollande’s actions in Syria. “They’re looking for an identity,” says Brisard. “They don’t recognize the values of our societies. They’re keen on joining radical Muslims and they’re keen to fight. They romanticize the struggle.”

Mostefai’s family appears to be cooperating with authorities. His brother, Houari, who lives in the Paris suburb of Bondoufle, turned himself in to authorities when his brother was identified as one of the attackers after his finger print—from a severed finger, as Mostefai was one of the suicide bombers who blew himself up at the Bataclan—came up in the French criminal database. Neighbors say Houari, a night guard at a handicapped facility, rarely spoke of his brothers and to their knowledge hadn’t spoken with Omar since he reportedly traveled to Syria.

Authorities on Sunday said two more of the attackers have been identified as French citizens living in Belgium before the attacks. Their names have yet to be released. At least one French paper reported that one of those attackers was Omar’s other brother. European officials also widened a manhunt on Sunday for Belgian-born Abdesalam Salah, the alleged eighth assailant who appears to have fled the attacks alive.

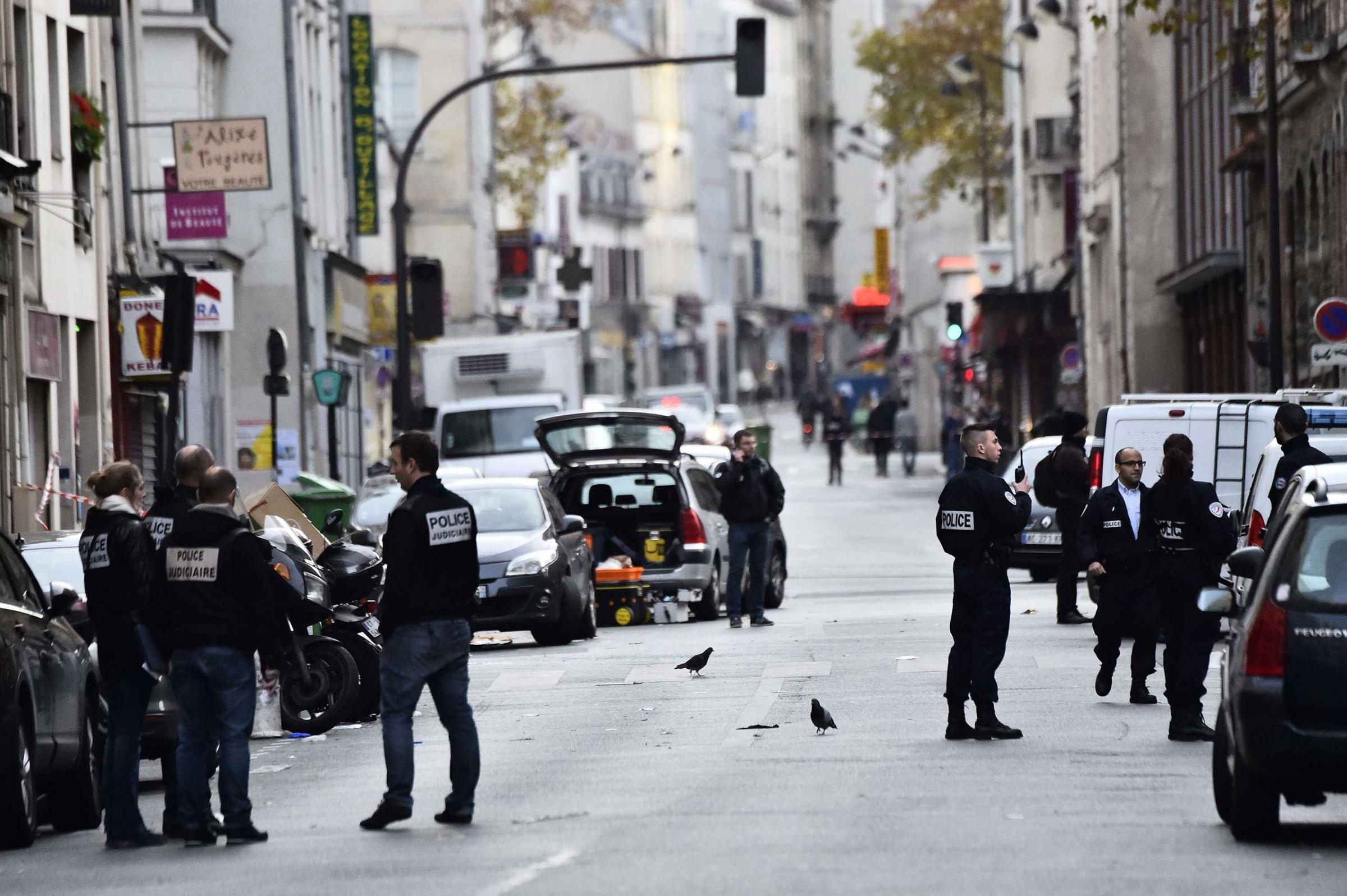

In the wake of the attacks, Hollande declared war on ISIS, promising more bombing in Syria. Such moves, Benraad believes, will only worsen the problem. “We can enhance security measures. We can multiply the number of policeman in the street, but it’s not going to work, nor is the bombings going to work,” she says. “It won’t work until we fix the problem in our societies.”

Witness Paris Mourn the Day After Deadly Attacks

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com