French fighter jets struck key targets of the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS) late Sunday night, in a fierce bombing raid on the Syrian city of Raqqa, making good on President François Hollande’s promise for a gloves-off retaliation against the terrorist group, in response to the devastating terrorist attacks in Paris, which the French leader had called “an act of war.”

Around 10 p.m. Sunday — exactly two days after the attacks in Paris — French television announced that the country’s military had dropped 20 bombs on Raqqa, the headquarters of ISIS’s so-called caliphate. Defense officials said the military strikes aimed to destroy an ISIS munitions depot and a training camp for jihadist fighters. The strikes come as French police conducted a massive manhunt for an eighth attacker who escaped after Friday night’s killings.

In a weekend that has been filled with anguished emotion and raw pain, the French bombers struck Syria while a solemn memorial ceremony was under way in Paris’ soaring medieval Notre Dame cathedral, and while hundreds of people were gathered for spontaneous candlelight vigils at the sites of the attacks in the eastern 10th and 11th districts.

The operation came just hours after U.S. officials — including the top American diplomat in France, U.S. Ambassador Jane Hartley — made it clear that Washington had been in close contact with French officials since the moment after Friday night’s attacks, which killed 132 people and injured about 350 others.

Within an hour of the attacks, the country stunned and shocked, Hollande imposed a national state of emergency and promised he would deal with ISIS in a “ruthless” manner, calling the terrorism “an act of war.”

All weekend French officials have carefully been preparing the country for likely military retaliation — a move that draws France far more deeply into the military fight against ISIS than it has been until now. They have made it clear that Friday’s attacks were a militaristic operation, conducted by a sophisticated network with international planning. In an interview published Sunday, Defense Minister Yves Le Drian told the Journal du Dimanche paper that France “has been struck by an act of war,” and that the country had to take out “all the capabilities” of ISIS. “Daesh [the Arabic name for ISIS] is a real terrorist army and we must fight it everywhere and tirelessly,” he said.

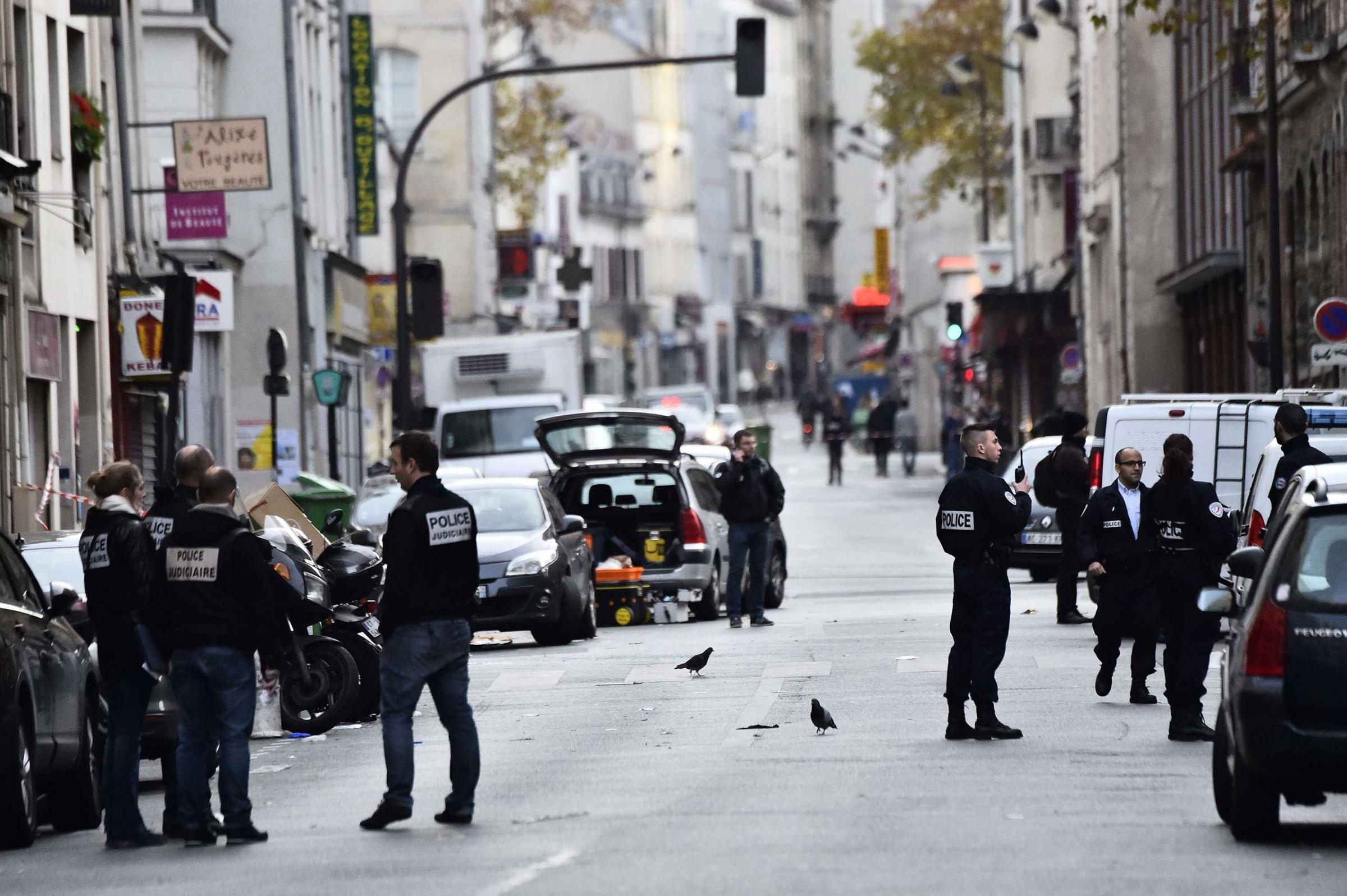

As the frenzied chaos and shock from Friday night’s terrorist attacks in Paris settled into a sprawling criminal investigation, police said on Sunday they were hunting for an eighth attacker who might have escaped during the assault that killed at least 129 people and injured hundreds more.

The police issued a wanted note late Sunday with a photograph of Brussels-born Salah Abdeslam, 26, warning people who spot him that he is dangerous. “Do not intervene yourself,” it said, the AP reports. Late Sunday, Belgian officials told reporters that about 70 people were now under arrest there.

French officials told the AP that police questioned and released Abdeslam hours after the attacks, after pulling his car over near the Belgian border.

With police piecing together who pulled off the deadliest operation in modern French history, a portrait is emerging — deeply worrying for many French — that these foes are not some remote force, but people who appear to be deeply knitted into their society.

Overnight, France’s crack anti-terrorist police, which goes by its initials RAID, arrested six relatives of one of three suicide bombers who stormed the Bataclan concert hall in eastern Paris late Friday and massacred 89 people. Police quickly identified Omar Ismail Mostefai, a 29-year-old half-Algerian Frenchman, from the fingerprint on a severed digit, because he had a long rap sheet of petty crime dating to 2008. He had lived in Chartres, a town 60 miles southwest of Paris famous for its medieval cathedral.

On Saturday evening Paris prosecutor François Molins told reporters that police had regarded Omar Mostefai as “a radicalized person with a security report,” but not as somebody with specific links to terrorist organizations — a fact that would certainly have made him a target for arrest before Friday’s attacks. On Sunday, Mostefai’s older brother turned himself in to police after hearing of his involvement, telling the French news agency AFP shortly before that he had not spoken to his brother for a long time. So too did one official at a mosque in Chartres where Mostefai had been a frequent worshipper. “We practically have not seen him since 2013,” the mosque official told France 24 Television.

Details have filtered out in spurts, often contradictory and unconfirmed by police. Just as hospital officials briefly put the death toll at 132 Sunday evening only to revise it back down to 129, Molins initially said the attackers were made up of seven people in three tightly coordinated groups. But police sources told reporters on Sunday that an eighth man appears to have escaped in the chaotic climax to the assault, when anti-terrorist SWAT teams stormed the Bataclan theater and ended the night of terror. It was not clear on Sunday whether the missing attacker was among the three people whom Belgian police arrested in the early hours of Saturday morning, since some of those involved in Friday night’s assault fled to Belgium, where three of the attackers lived.

Now Parisians are grappling with how their gracious city has been transformed — just 10 months after the Charlie Hebdo attacks in January, which killed 17 people. Under a national state of emergency imposed by Hollande hours after the attack, police have expanded powers to impose curfews and cordons around specific neighborhoods and to arrest anyone who questions their actions; Hollande declared Friday’s assault “an act of war,” a phrase not used after the January attacks. Likewise, Prime Minister Manuel Valls early Sunday said he believed the country was “at war.”

Yet for many French, it is unclear whether that tough talk and emergency measures will be enough to ward off further attacks.

Still reeling from the tragedy, many Parisians stepped out into the quiet streets on Sunday, in spring-like sunshine, to gather in groups near the sites of the attacks in Paris’ 10th and 11th districts, singing, playing guitars and laying flowers outside the Bataclan, and at the restaurants where many others died from gunfire.

In the Republique Square a short distance from the Bataclan, some young Parisians sang, while others sat on the steps, staring contemplatively, one with her head in her hands, weeping. “Parisians are sad and disappointed but mostly angry,” said Florent Vigneux, 26, a physiotherapist, standing in the square. “Eventually we will recover our day-to-day spirit again,” he said. Late Sunday, hundreds of mourners in the square fled in panic as loud bangs could be heard nearby; police said later it was firecrackers.

The scare underscored the difficulty of figuring out what exactly the French government and police could do to reassure people that no other attacks lie ahead; in fact, many people interviewed since Friday night have told TIME that they believe more attacks are almost inevitable. “There are not a whole lot of options,” Vigneux said. “It is very complicated. They have to stop all the activity in Syria itself.”

All day Sunday, Hollande holed up in the Élysée Palace with French officials, as well as his political rival former President Nicolas Sarkozy, in an attempt to unite deeply divided politicians, so that he can craft a strategy to retaliate for the attacks and to dismantle jihadist networks. Sarkozy, who is maneuvering to retake the presidency in 2017, said early Sunday that he believes there should be a “drastic” change in foreign policy. “We must draw conclusions on the situation in Syria,” he told reporters. “We need everyone to help fight the Islamic State, notably the Russians.”

Those changes could include reimposing border controls within the 28 E.U. countries. Police uncovered at least one Syrian passport among the dead attackers, which Greek officials said belonged to a man who had landed illegally on Leros island, among thousands of migrants on Oct. 3. Sunday’s Liberation newspaper, citing unnamed sources, said an Egyptian passport was found in the attack against the stadium, though the Egyptian ambassador to France said the passport belonged to a victim who was attending the football match.

This year’s migrant crisis has already fractured politicians, with right-wing parties gaining ground. On Saturday, National Front leader Marine Le Pen — whose party is the clear front runner in next week’s French regional elections — told reporters that France should strip dual citizens of their French nationality if they have radical views. “France is not safe, it is my duty to tell you,” she said. She said the country “must ban Islamist organizations, shutter radical mosques, deport foreign hate preachers” — all measures that go far beyond anything the current government has proposed.

Witness Paris Mourn the Day After Deadly Attacks

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com