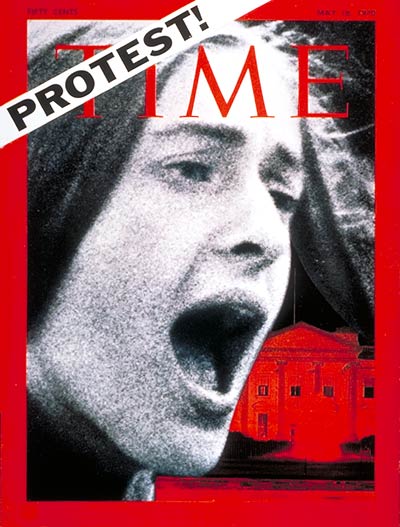

This week’s events at the University of Missouri, where a threatened strike by the football team forced the resignation of the President of the University system and a chancellor, inevitably remind Americans of a certain age of the late 1960s. Beginning in 1965, and especially from 1968 through 1970, student revolts struck campuses all over the country. The events at the University of Missouri—which already seem to be expanding to major protests at Yale and on other campuses—may well portend a similar series of campus revolts that, like those of the 1960s, could have national political consequences.

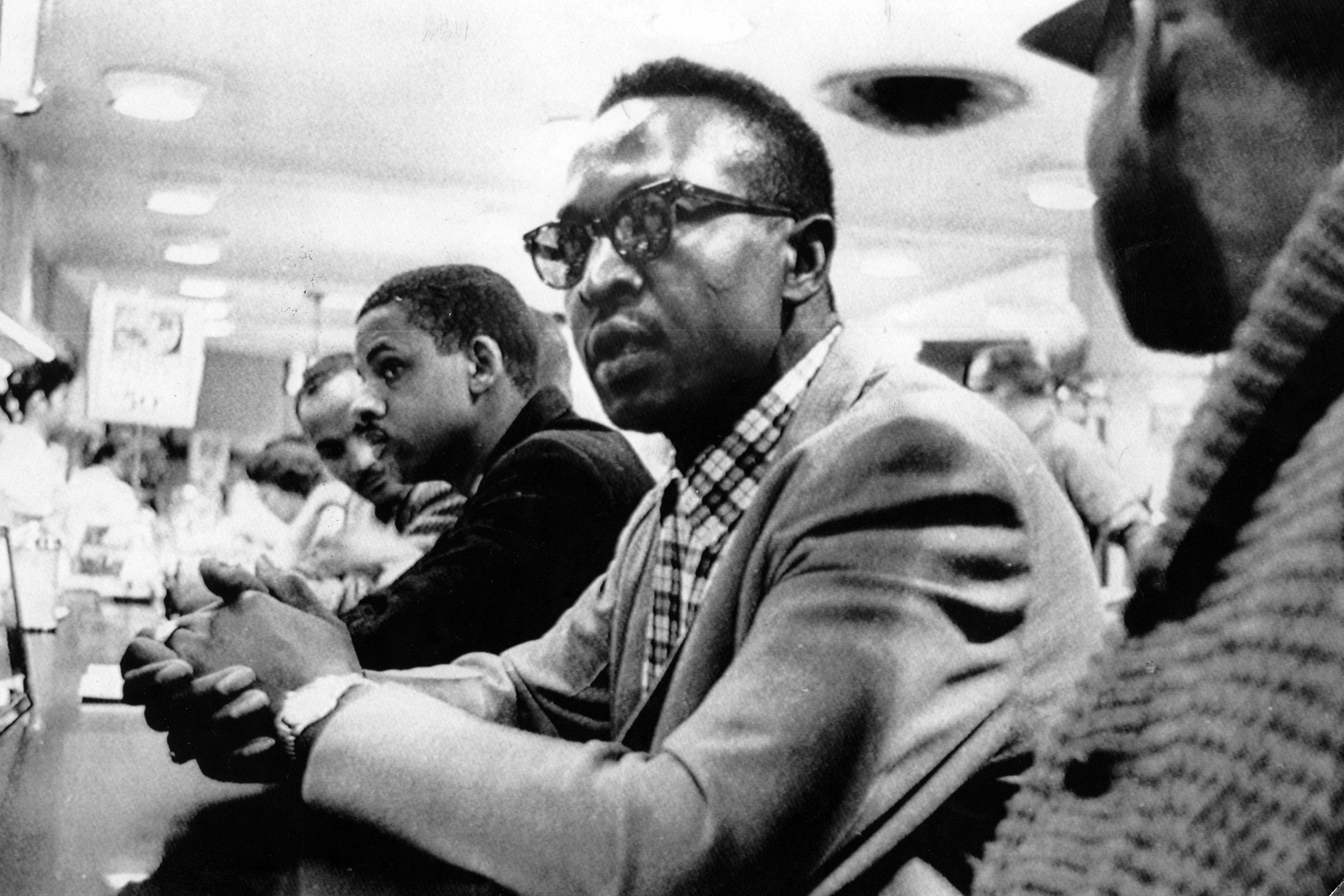

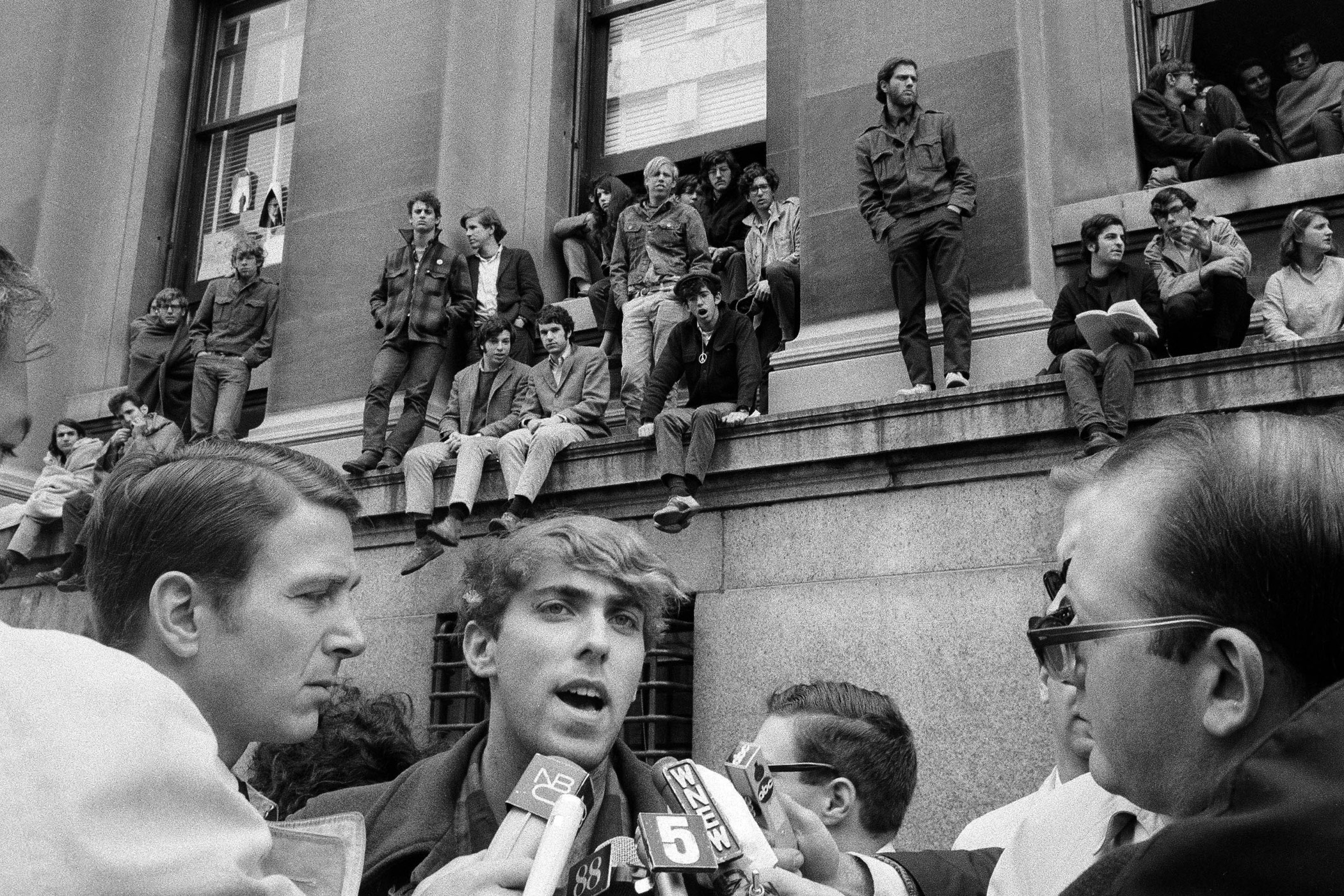

By 1969, thanks in part to national television coverage of early campus protests, there was a script for these events. The process would start with student demonstrations against the Vietnam War and federal government presence on campus, particularly ROTC. Students would occupy university buildings, sometimes violently. Administrators would respond by calling in the local police or the National Guard to remove them. When protesters were roughly removed and arrested, neutral opinion on the campus would turn against the Administration, and students would boycott classes. They would present a list of demands—such as the elimination of ROTC, the admission of more minority students or the creation of a Black Studies department—and in many cases would get at least some of what they wanted.

They got something else too: a change to the mission of higher education. In response to the protests, colleges in the 1970s decided that their mission was not simply to study and teach about the world around them, but to create an environment free of racism, sexism and homophobia, and to promote of certain ideas of justice and progress.

The script for today’s demonstrations reveals that students have been thoroughly indoctrinated in that post-1970s concept, and that they believe more work along those lines needs to be done. A modern protest usually begins with reported incidents of prejudice on campus. Students respond, not so much against the perpetrators but against the administration for failing to create a sufficiently safe environment. If the university is less than sufficiently responsive, the demands escalate to include requests for administrators to be fired. And now, at schools with high-level football or basketball programs like Missouri’s, players may threaten to boycott games. Sometimes today’s demonstrators get what they want—Missouri’s president stepped down—and, even more often, various steps are taken to re-educate the student population about the virtues of tolerance.

At first glance, it’s easy to think that this link between the protests of the Vietnam era and those of today mean that the demonstrators are winning. However, activists should think twice before they celebrate. The results of campus protests in 1965-70 were mixed, and the same thing could easily happen now.

In 1964, before the Vietnam War, Lyndon Johnson had a 60% popular vote majority in the presidential election. The first big student protests at UC Berkeley helped elect Ronald Reagan as governor in 1966, and the anti-war and anti-draft protests did a great deal to help turn Johnson’s majority into nearly as impressive a majority for Richard Nixon and George Wallace, combined, in 1968, and a 60% majority for Nixon in 1972. Middle America had no sympathy for student protesters. On the nation’s campuses, anti-war activism was becoming less controversial, but the students’ parents, who had obediently done their job during the Second World War, were much less sympathetic. Inside the White House, Richard Nixon frequently remarked that student protests increased his appeal to the “silent majority” he depended on for support.

Despite 30 years of post-1960s sensitivity on campus and in the media, we now face the possibility of a repeat. While major newspapers freely use the language of campus protests, including micro-aggressions, transgressive Halloween costumes and safe spaces, potential swing voters may feel very differently. Even some liberals feel that campuses are becoming much too sensitive and overprotective. Republican primary polls are led by candidates like Donald Trump whose willingness to offend is their greatest asset. The Democratic base supports the protests, but it seems unlikely that many independent voters will be moved to vote Democratic next year by a new round of chaos on campuses. Like the Vietnam protests in 1968, such protests could trap a Democratic candidate between the part of their base that supports the students, and swing voters on the other side. Even as student protesters score wins on campus, history shows that their victories may prove too bitter for the world they’ll enter once they graduate. Liberalism suffered critical defeats in 1966, 1968 and 1972, and another defeat next year would profoundly reshape the nation.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

David Kaiser, a historian, has taught at Harvard, Carnegie Mellon, Williams College, and the Naval War College. He is the author of seven books, including, most recently, No End Save Victory: How FDR Led the Nation into War. He lives in Watertown, Mass.

See 7 Times Student Activists Created Change

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com