In a two-part series, art photographer Mark Steinmetz and curator Charlotte Cotton review the Museum of Modern Art’s latest opus – Photography at MoMA: 1960 – Now. They offer contrasting views about the Museum’s curatorial choices as the institution moves away from John Szarkowski’s legacy. Read Steinmetz’s take here.

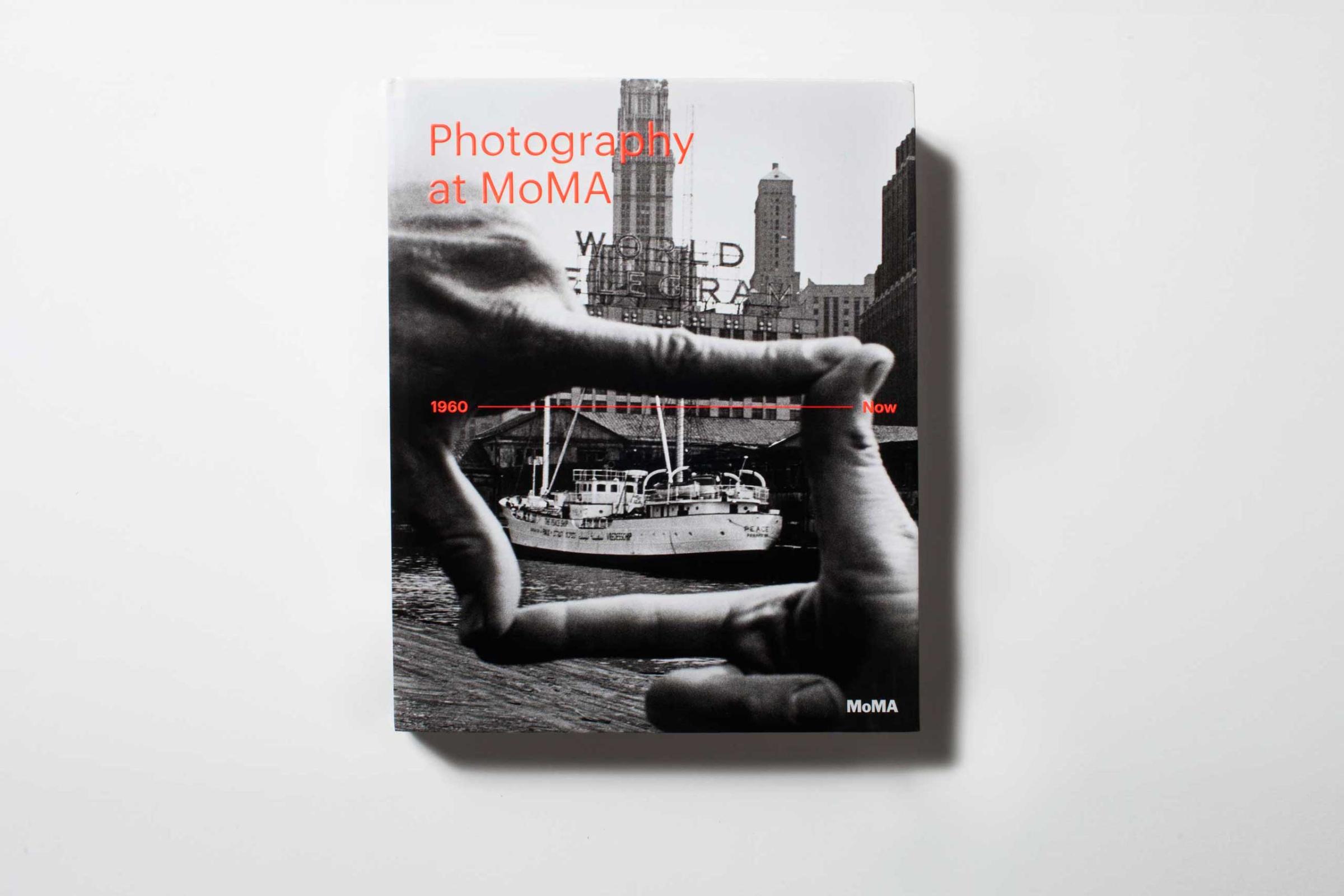

Photography at MoMA: 1960 –Now, the first of three volumes surveying the history of photography through New York’s Museum of Modern Art’s collections, delivers exactly what the title promises and we might expect. Namely, a beautifully illustrated, six-decade story of where photography can be situated within the story of Modern and Contemporary Art, drafted by the dominant institutional architect of that story.

The book’s various introductory essays, penned by the Museum’s director Glen D Lowry, the chief curator of photography Quentin Bajac and curator Sarah Hermanson Meister, all speak to the idea of MoMA as the bustling Valhalla where photography’s creative ebb and flow is legitimized and has, at points, gained its ascendance as a serious cultural subject.

With the institutional scene set, each subsequent chapter of marvelous reproductions begins with a short essay by MoMA photography curators and notable academics that defines a photographic theme (from Conceptual Art to post-Internet) through groupings of MoMA’s photography holdings.

There is something very clean about this book – not just it’s spacious design and easy navigation, but in its omissions and the sense that we get of observing a very swan-like glide through photo history from above the waterline, with muddy water making the frenetic, inelegant trashing of the muscles that actually drive its motion almost entirely invisible.

There are clues in this book to the reality of an art institution that has been dedicated to collecting in media categories despite artists not holding to those material divisions for decades. Note how most of the conceptually-driven gems from the 1970s and 1980s were acquired in the 2000s, suggesting an internal and long-established battle about the mandate of MoMA’s legendary photography department. A quick tally from the image captions of the amount of acquisitions from pan-media-focused – The Contemporary Arts Council, the Fund for the Twenty-First Century, as-well-as the wonderful MoMA Library – alerts us to the plain fact that if this book’s content had been drawn from the photography department’s core interests and donor relationships, it would have been a very different photo-story being told in this book.

I suspect I am not alone in presuming that the international scope of contemporary art photography at MoMA since the late 1980s is hugely reliant on its ‘New Photography’ exhibitions, which began in 1987, and historically gave space to young artists and curators to present new trajectories in photographic practice. Part of me wishes that the ‘New Photography’ project was the sole subject of this first ‘Photography at MoMA’ volume, especially given the expanded version – ‘Ocean of Images’ – currently on show.

You cannot help but wonder at the extent of the tussle in recent decades (although there is no account of the actual curators beyond its reigning chief curators before now) about deviations from the vision of the still-revered chief curator John Szarkowski, who established an indelibly essentialist criteria that the best photographs cannot be created with any other medium.

Szarkowski’s connoisseurship inevitably created a pretty hermetic and separated set of ideals for photography within a timespan (Szarkowski was chief curator from 1962 to 1991) within which photography moved from needing safe isolation and special attention – like a sickly child – to having its identity as a medium and a discipline fabulously imploded by artists, along with the other technics of art-making.

While Szarkowski and possibly his replacement Peter Galassi are remembered by the chosen few (separated from ‘the many’ that constitute the actual story of independent photography) as creators of a social space where ideas about photography could be discussed, the reality of the tone set by MoMA’s photography department in this book shows that collections can be exceptionally mute. When seen in isolation, their articulation of what was truly and culturally at stake at any point in the history of photography-as-art seems absent. As is the full sense of where its photography department currently stands in terms of its own curatorial history.

The book’s final chapter, which brings us to the present day, has post-Internet practices positioned neatly into a trajectory of “experimentation” that begins with the early 20th century avant-garde movements, rather disappointingly suggesting that the ways in which artists are responding to Web 2.0 and our current day “image explosion” is situated at the tail end of MoMA’s trademark account of Modern and Contemporary Art, as if the medium itself and many of its most exceptional contemporary creators have had no material effect other than as illustrations upon the story of photography that MoMA will resolutely tell.

Charlotte Cotton is a writer and the Curator in Residence at the International Center of Photography in New York City.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com