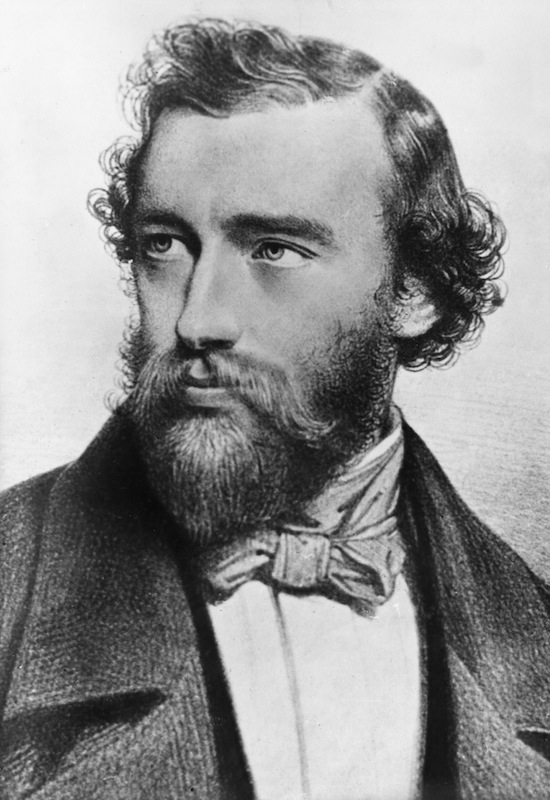

It took decades—a century even, depending how you count—for Adolphe Sax’s invention to take its place in history. The Belgian instrument maker, born 201 years ago, on Nov. 6, 1814, patented the saxophone in the 1840s. The new instrument, with a woodwind reed and a brass body, was a good fit for a military band, but it didn’t get much respect from the musical establishment.

As TIME later explained:

As a boy in early 19th century Belgium, Adolphe Sax was struck on the head by a brick. The accident-prone lad also swallowed a needle, fell down a flight of stairs, toppled onto a burning stove, and accidentally drank some sulfuric acid. When he grew up, he invented the saxophone.

Only a child that familiar with adversity, contend critics of the saxophone, could have foisted such a contraption on an unsuspecting world. A hybrid of the brass and woodwind families, the instrument is the perennial Cinderella of serious music. Its rich, sometimes dozing sound has never found a permanent place in the symphony orchestra, although after its invention in 1840 such French composers as Berlioz and Massenet experimented with it. In Germany only Richard Strauss, whose Domestic Symphony included a quartet of saxes, regarded it as anything but a yeoman of military bands.

After Sax’s death, the saxophone finally found an established place in the world of music when it came to the United States and made its mark in the world of jazz—and, eventually, rock and roll. Its success in those popular genres, however, actually hurt its reputation in the world of classical music. By the 1920s, it was so closely associated with jazz that many classical purists dismissed it altogether.

Even so, at least one musician did not give up hope that the saxophone could become a well-respected classical instrument: in the 1950s, saxophonist Marcel Mule helped show that, in TIME’s words, the instrument could produce “an open, evenly controlled sound that could sing with a clean vibrato or a finely trimmed staccato, swell robustly and solidly with no trace of the breathy ‘air sound.'” Mule’s challenges were many—including the fact that, even when he formed a classical saxophone quartet, there wasn’t any music out there for them to play—but he remained driven to change the instrument’s reputation.

“I have one mission in life,” he told TIME. “That is to make people take the saxophone seriously. It’s time they discovered the nobility of this spoiled instrument.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com