It was a new and unique form of entertainment when it was first introduced. And that’s still true today, 75 years after the world first encountered Fantasia on Nov. 13, 1940. Fantasia was not simply a film or a concert. Instead, it was a hybrid, a selection of great orchestral works conducted by Leopold Stokowski, played by the Philadelphia Orchestra and illustrated by Walt Disney.

As TIME recounted in a cover story that week, the project had been in the works for years. Though Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs would be Disney’s first full-length animated film, he had wanted to do something operatic even before that. It was Stokowski who, during a trip to California in 1938, the year after Snow White, turned the idea into a reality by suggesting that he could conduct the music for a Mickey Mouse version of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, set to the piece of that title by Paul Dukas.

But a problem quickly emerged: the resulting short was just too good—and finishing it would be too expensive. In order to justify the cost (which would top out at around $2,250,000, or more than $38 million in 2015 dollars), it would have to be a feature film. Except that The Sorcerer’s Apprentice wasn’t long enough on its own. Disney, of course, had a solution.

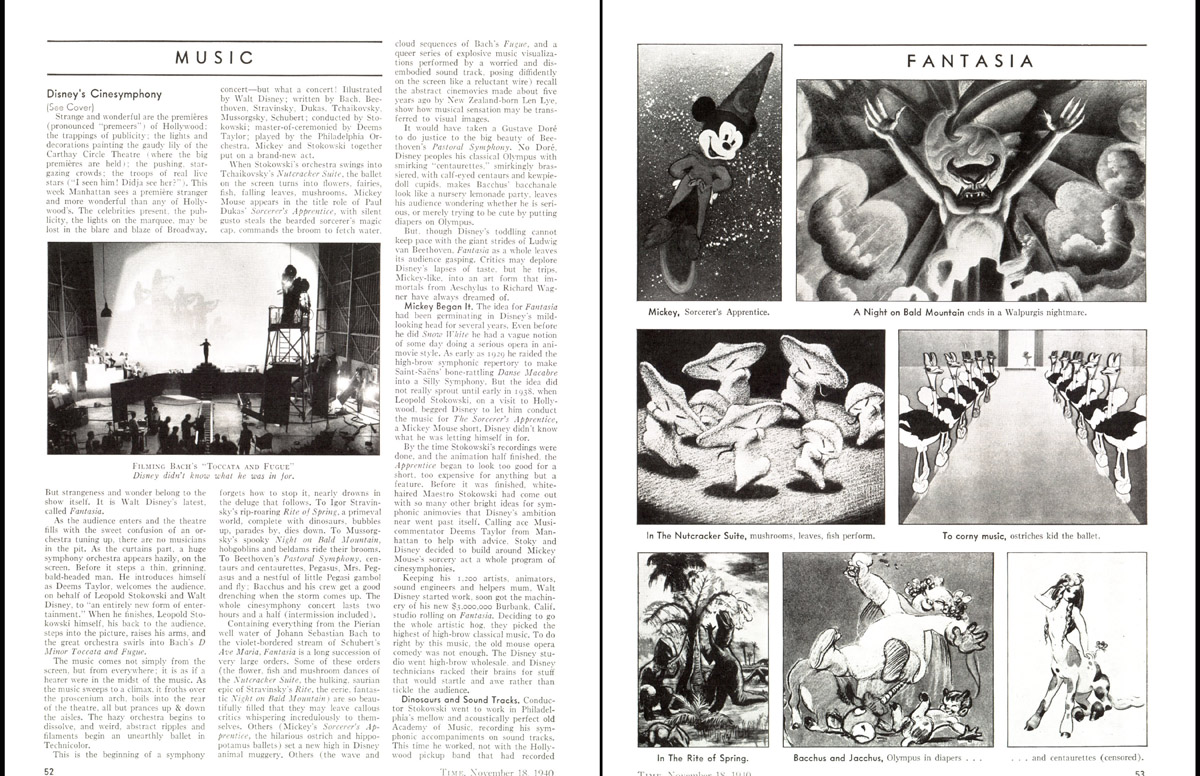

“Keeping his 1,200 artists, animators, sound engineers and helpers mum, Walt Disney started work, soon got the machinery of his new $3,000,000 Burbank, Calif, studio rolling on Fantasia,” TIME explained. “Deciding to go the whole artistic hog, they picked the highest of high-brow classical music. To do right by this music, the old mouse opera comedy was not enough. The Disney studio went high-brow wholesale, and Disney technicians racked their brains for stuff that would startle and awe rather than tickle the audience.”

Meanwhile, Disney sound engineer Bill Garity invented the new technology—”Fantasound”—that would allow the cinema audience to hear the music in its full glory. Each orchestra section would be recorded on its own track, which would then be woven back together. The system was not without its drawbacks: the equipment would have to be moved around between theaters, which meant that only 12 cineplexes could show the original Fantasia at one time. On the other hand, the resulting “roadshow” production made Fantasia even more of an event than it already was. “Music lovers crowed that more ears would be saved for Beethoven by Fantasia than by all the symphonic lecture-recitalists in the U. S.,” TIME declared.

And the result was worth it, TIME’s critic swore: though not every pairing of animation and music was equally great (“Disney’s toddling cannot keep pace with the giant strides of Ludwig van Beethoven”) the experience would leave audiences impressed: “Critics may deplore Disney’s lapses of taste, but he trips, Mickey-like, into an art form that immortals from Aeschylus to Richard Wagner have always dreamed of.”

Read the full cover story, here in the TIME Vault: Disney’s Cinesymphony

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com