In 1980, Juan Cordero slipped into his 9-year-old daughter’s room to kiss her goodbye as he left for America. She pretended to sleep. She and her mother had been the ones to urge him to go. They would be reunited soon, she said. She didn’t want to make it any harder for him so she breathed even asleep breaths and kept her eyes closed. She never saw him again.

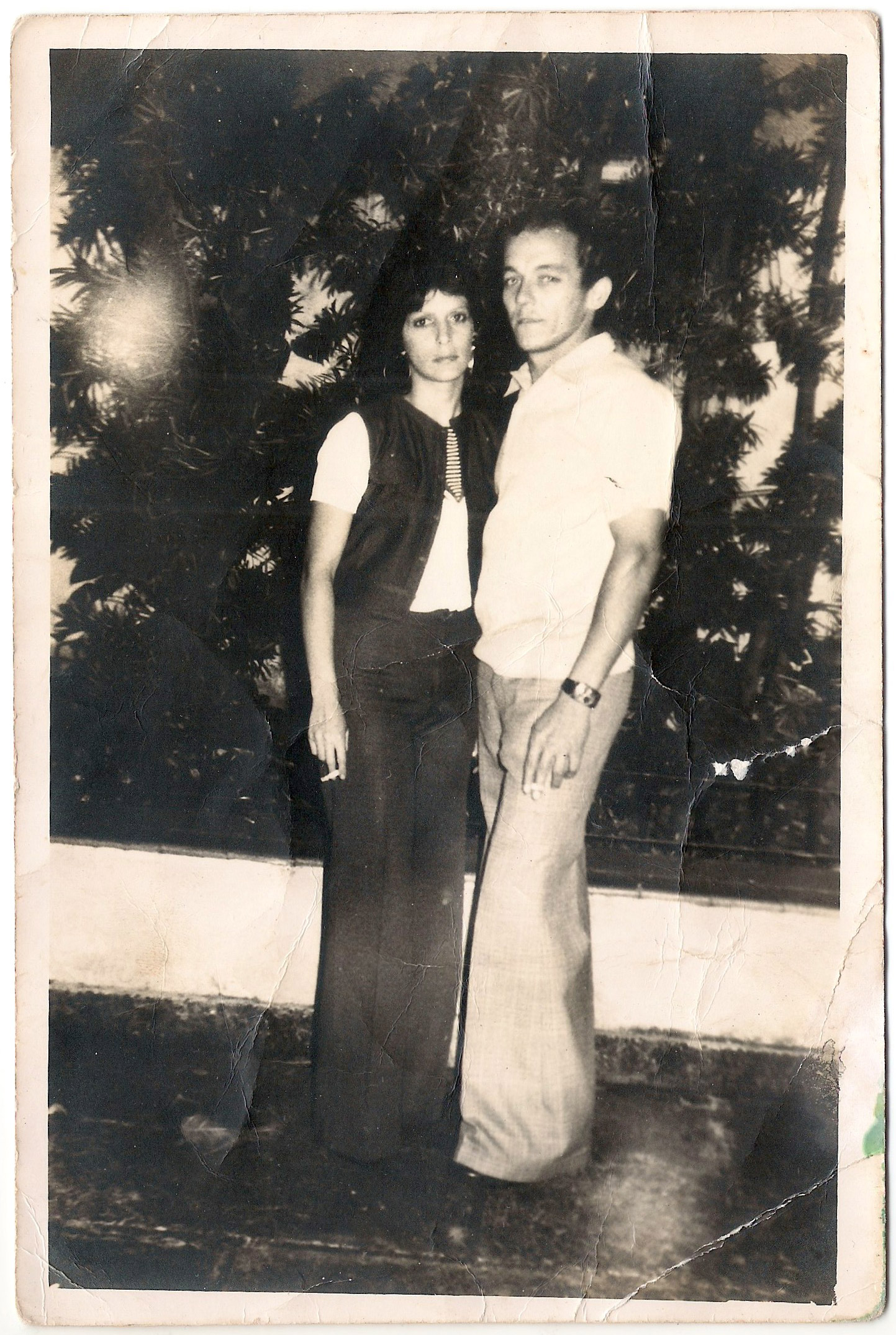

Juanito was my mother’s cousin who, like thousands of other Cubans, arrived to the U.S during the 1980 Mariel Boatlift. The waters of the Florida straits have split my family for the last half-century leading up to the historic normalization of relations between the United States and Cuba this year.

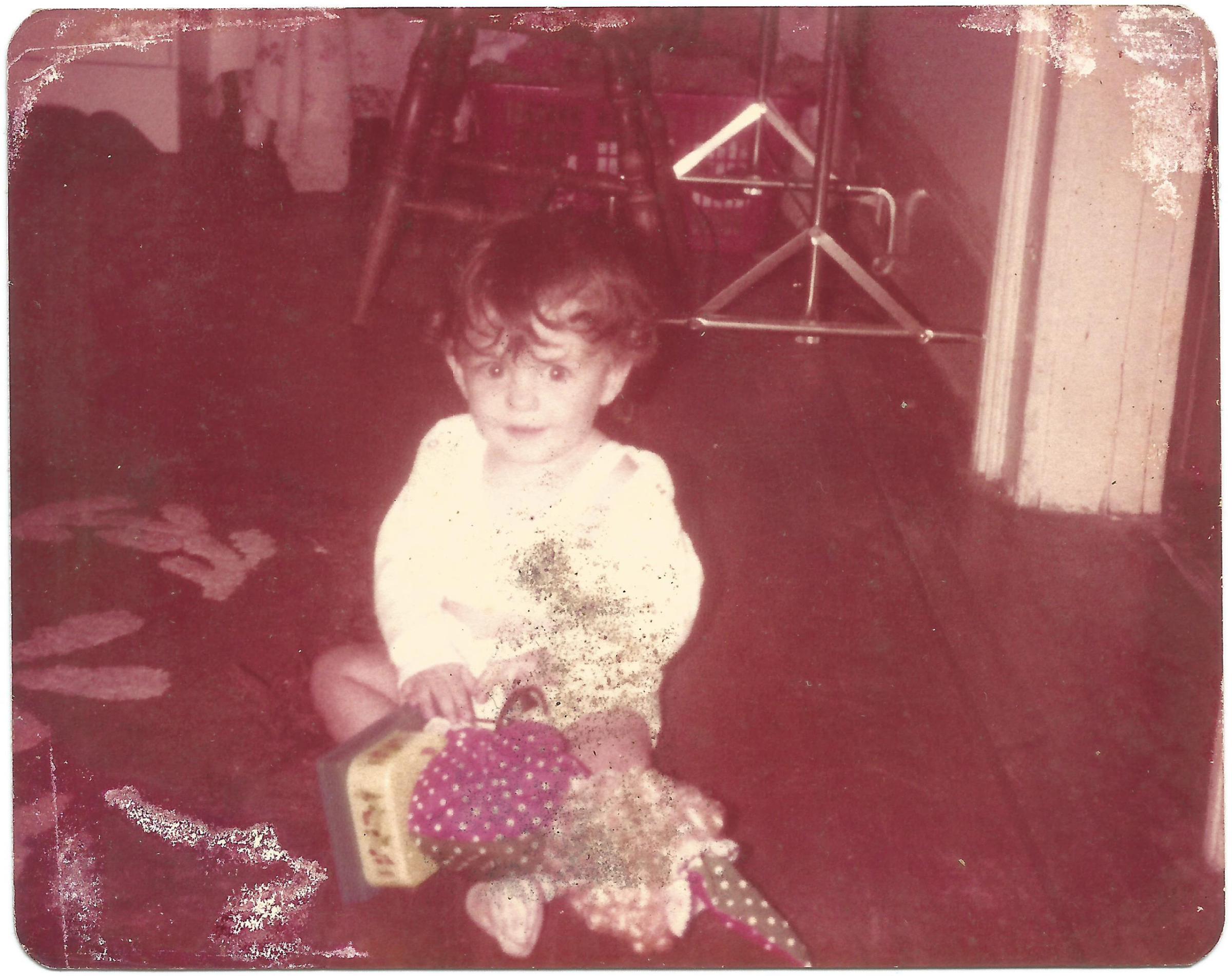

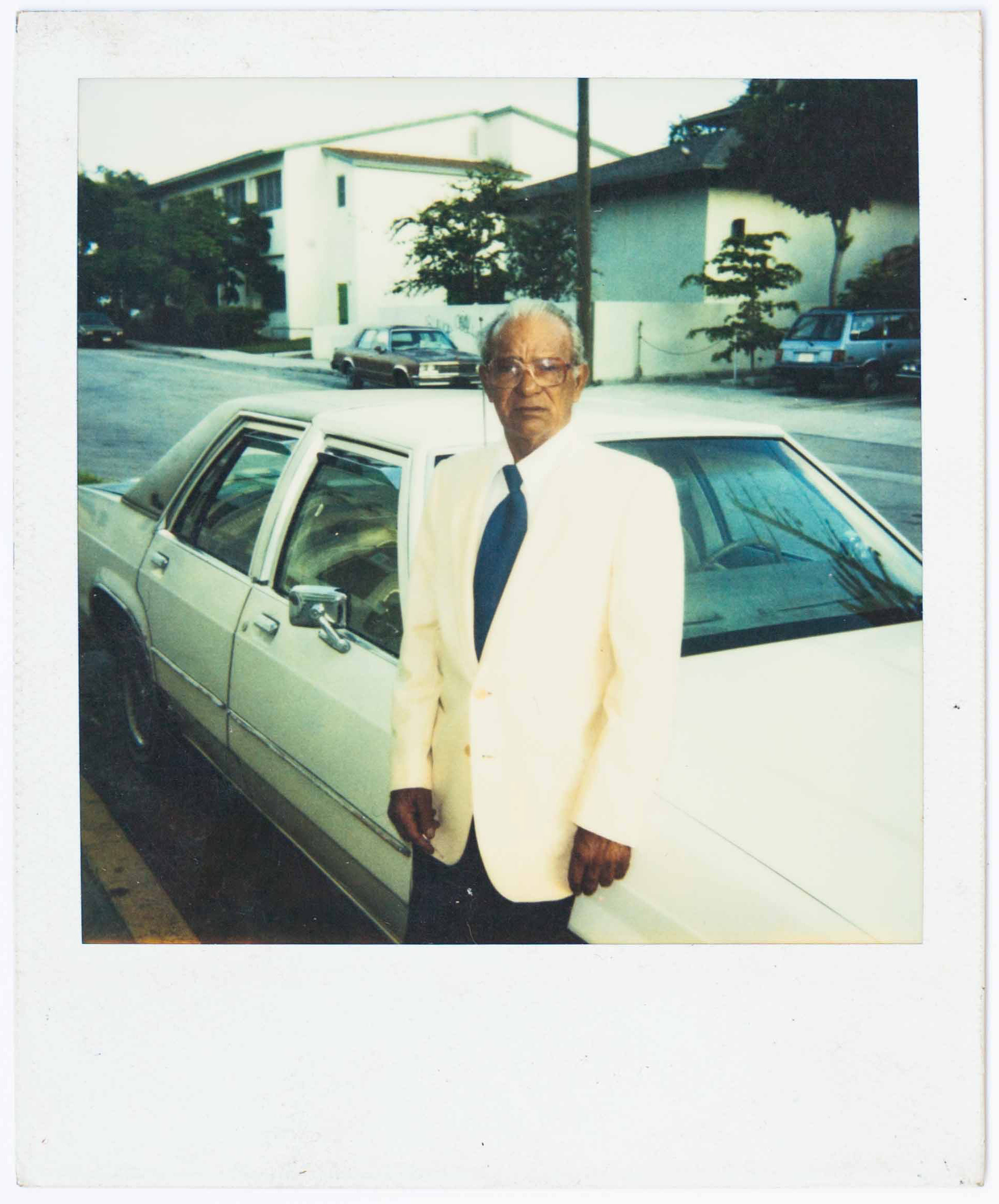

I’m a Cuban-American photographer, and though I grew up in the U.S., lately I spend most of my time in Havana. This year as my grandmother grew ill with cancer in San Francisco, my family and I reminisced about her life. As she passed away in May, we shared stories and photos (like those in the slideshow above), and what surfaced was the depth of my grandmother’s impact on the lives of countless people.

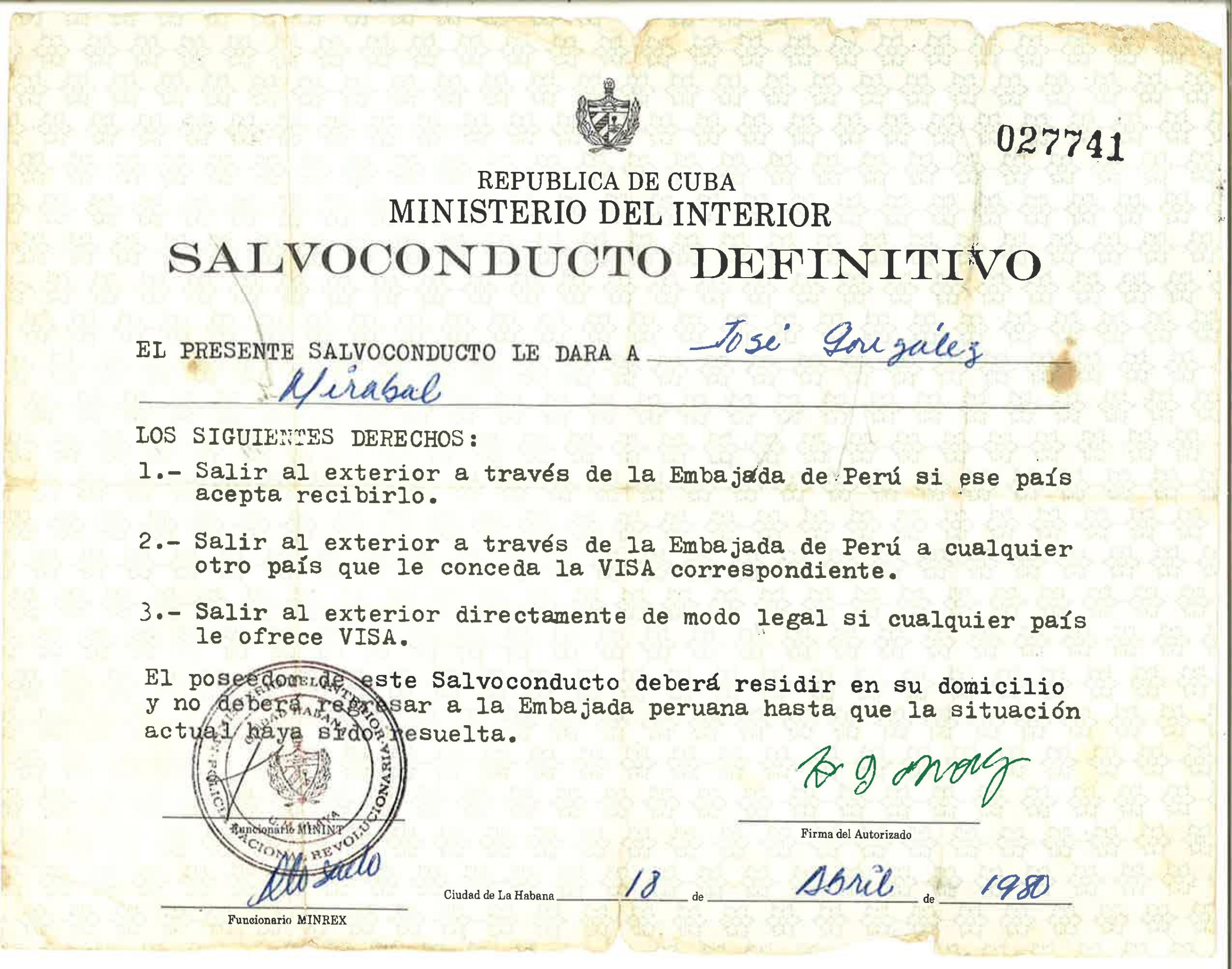

Sira Cordero Mesa de Gonzalez—whom we all called Mima—was the youngest of nine brothers and sisters. She left Cuba in 1960 and took my mother, age 12, and her sisters. They left hundreds of relatives behind, many of whom later crossed the water in 1980, fleeing Cuba. The Mariel Boatlift began in April of 1980, when a group of Cubans stormed the Peruvian embassy in Havana, killing a guard. Fidel Castro asked the embassy to return the attackers, but he was refused. Within a few days 10,000 Cubans had filled the grounds of the Peruvian embassy, claiming asylum. Soon after, Castro announced that anyone who wanted to leave the country could do so from the Mariel port. Before the Boatlift ended on Oct. 31, 1980—35 years ago this weekend—some 120,000 Cubans came to the United States.

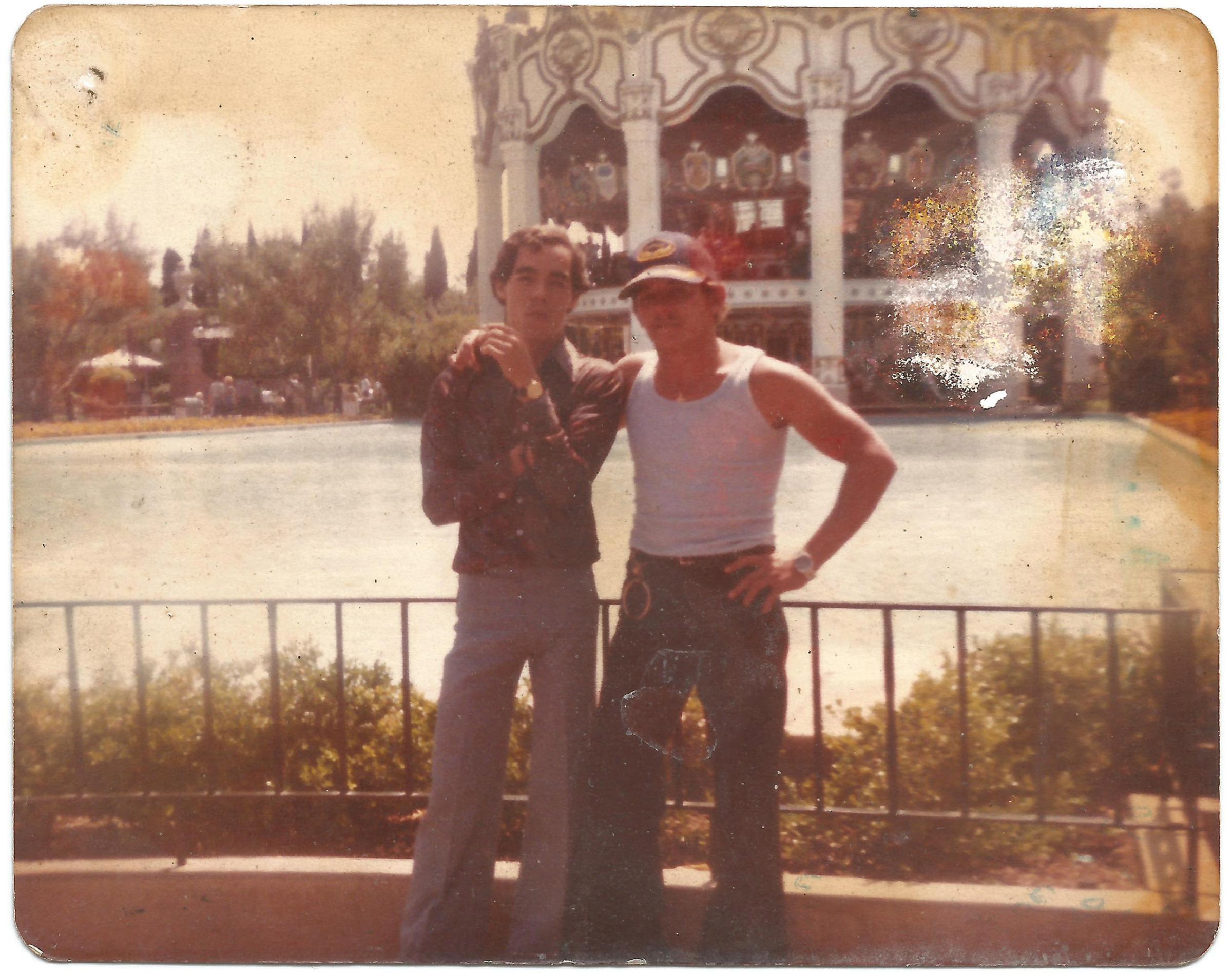

At that time, my grandparents in California took in anyone who needed a home, giving both the new arrivals and their children in the U.S. a semblance of togetherness. Their house on London Street was a welcome place for anyone passing through. “It was lovely to have these cousins around, to have family for the first time,” my mother told me.

Six Marielitos, as the refugees were called, went to San Francisco to live with my grandparents Sira and Manuel Gonzalez. There was Pepe Cordero, a taxi driver in Havana. Chancing upon the riot at the Peruvian embassy, he stopped his car to join the asylum-seekers and spent 18 days inside the premises until being released to the U.S. All he knew was that his aunt lived on London Street in San Francisco. The authorities were able to locate Sira and reunite them; he was the first Marielito to arrive in the Bay Area.

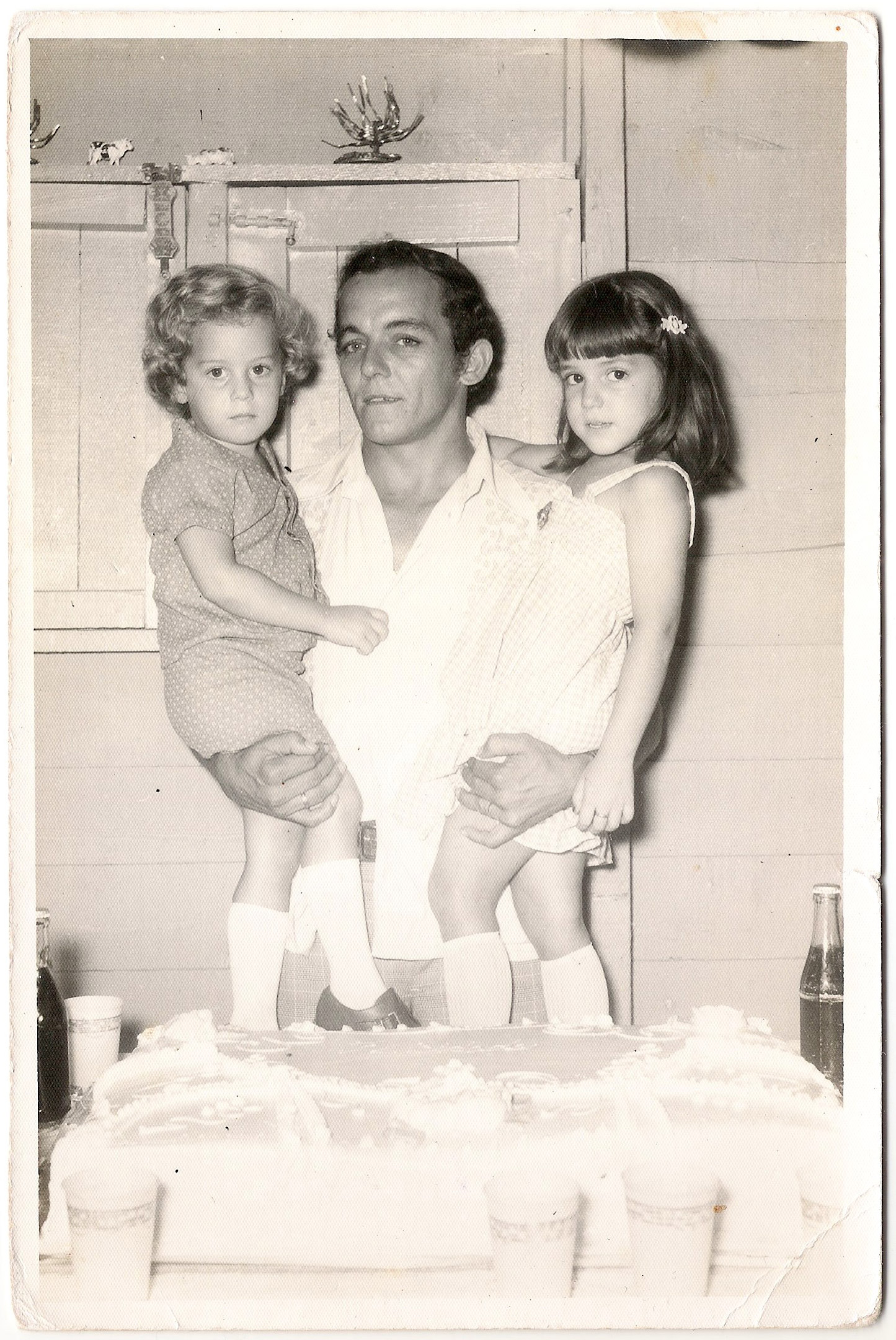

After Pepe came Juanito, also Sira’s nephew. Like most of the Marielitos in my family, he left behind a wife and two children, including his daughter Mileydis. Juanito was the first in the neighborhood to correspond with Cuba, says his daughter, sending a package to his family with clothes, letters and photos. On Christmas Eve 1982, he was killed in a small restaurant he owned in San Francisco’s Mission District, while preparing Noche Buena dinner. Mystery surrounded the death of Juanito, whose brother and brother-in-law from Cuba had had brushes with the law. His daughter recalls that he’d written home to Havana shortly before his death, saying that, “he was going to do something and that possibly would cost him his life.”

Jorge Cordero, Juanito’s brother, had been jailed at age 15, until he was taken out of Cuba at 21 and sent to the U.S. ”When we left Cuba we had to forget that it existed because otherwise one would live their life suffering here,” he recalled during a recent conversation in San Francisco. “You couldn’t communicate with anyone there or anything.”

Living in Havana now and working as a photojournalist, my family history colors every experience I have. As I covered the announcement of renewed relations between the U.S. and Cuba, the matriarch of our family was home in California, receiving treatment and hoping to get well enough to visit Cuba one last time. As I thought about my Mima, missing her and wanting to be by her side, I worked even harder at the stories I photographed, feeling the only way I could justify being away was to make her proud. I was documenting a moment in history she thought she’d never see, in her homeland, a place she never forgot and talked about every day.

Cuba is a paradoxical place, almost impossible to describe any other way. My family in Havana constantly says, “Isn’t is crazy? All of us wanting to leave, and you coming to live here!” No one seems to understand what I’m doing living in Centro Habana when I could be hanging out in Brooklyn or San Francisco. But I couldn’t miss this.

For the Marielitos, life in the U.S. worked out better for some than for others, but the London Street house was a landing point where they all found the warm welcome of family. “My cousins did all the work, running around to doctors to help me [with legalization paperwork],” says Silvio Cordero, who also found refuge with his aunt Sira. “If I hadn’t had family here I wouldn’t have made it.”

But, even as Cuba and U.S. move toward a reunion of their own, one piece of my family is still missing: Juanito’s daughter Mileydis says that her one wish is to find her little bother Omar, who, she’s never met. After her father’s death, Omar’s mother moved with him to Miami and lost contact with my family.

Because my grandma’s mission was to help those in need and keep family together, and because now that role has been passed along to me, I hope is that this story will find Omar, bringing him back into contact with our family, all these years later.

Read TIME’s 1980 coverage of the boatlift: Exodus Goes On

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com