A spacecraft that knows how to repair or maintain itself hasn’t been built yet. That’s especially problematic when the one in question is the International Space Station (ISS)—which is larger than a football field, weighs nearly one million lbs. (454,000 kg) and required 115 different spaceflights just to get its components into orbit and properly assembled.

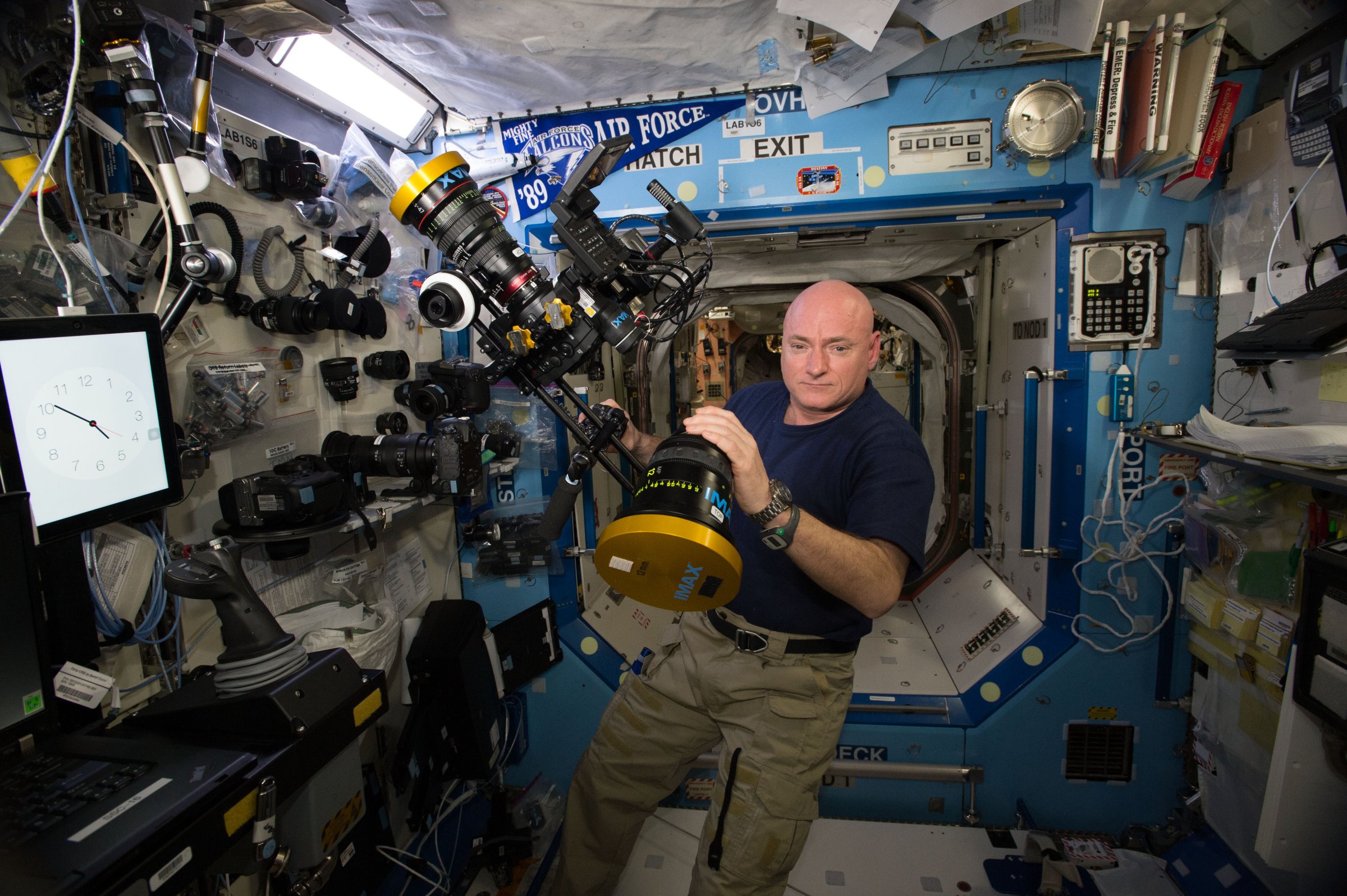

After 15 years of continuous occupancy, the ISS is in need of one of its periodic upgrades, and on Wednesday, astronauts and first-time space-walkers Scott Kelly and Kjell Lindgren will step outside to perform that much-needed work. The entire six-and-a-half hour walk will be streamed live on TIME.com, beginning at 6:45 AM E.T. (A second walk, scheduled for Nov. 6, will also be shown here.)

The first spacewalk—or EVA (extravehicular activity) in NASA’s preferred parlance—will mostly involve some basic electrical work, with Kelly and Lindgren running new cables along portions of the station’s length to provide power for docking ports that will be needed when new commercial crew and cargo vessels begin arriving in 2017. The astronauts will also install a thermal cover on a scientific instrument to protect it from the extreme temperatures of space, and will lubricate portions of the ISS’s robotic arm.

If that sounds like awfully unglamorous, awfully low-tech work, it’s because it is. Build the most sophisticated machine you want, it still comes down to the nuts-and-bolts business of, well, nuts and bolts.

But doing basic handyman work is radically different in space—and radically more dangerous too—and Kelly and Lindgren have been preparing for months for their orbital service call. Many of the basic protocols of any spacewalk are worked out far in advance of a mission, with practice sessions in NASA’s Neutral Buoyancy Lab (NBL), a 6.2 million-gal. (23.5 million liter) swimming pool with a full-scale mock-up of much of the ISS resting on its bottom. But some of the details can’t be fully validated until the astronauts are already in space, which is especially true in the case of Kelly, who launched to the ISS last March 28 for a marathon one year in orbit.

Any significant changes to the EVA plan are often beamed up to the crew first as a simple PowerPoint-type animations. Other fine points are worked out in the NBL and radioed up later the most granular detail possible—the precise torque that has to be used to tighten a bolt and how many turns it will need before it’s secure, for example.

Just which man does which job while they’re both outside is determined by experience, skill-set and a few other, non-negotiable considerations. Kelly, as the more senior of the two astronauts, will be lead spacewalker for the first EVA, which means he will be first out, last in, and generally command throughout the exercise. His suit will have the red striping used to indicate the commander. Nonetheless, for that walk, Lindgren will be assigned some of the more challenging work in some of the trickier areas of the station. Why?

“He has longer arms,” says NASA’s Grant Slusser, who will be the ground director for the first EVA. “They’ll be working in a really tight area.”

WATCH TIME’S SPECIAL DOCUMENTARY SERIES ON THIS MISSION (trailer below)

The mere business of getting the EVA suits ready can be a days-long job. Cooling loops that run through the garments like a human circulatory system have to be flushed with water to remove any contaminants. And while each suit is precisely tailored to the astronaut who will wear it, what fits on Earth may not fit in space, for the simple reason that without gravity, the spine may elongate a bit. Last minute adjustments are thus necessary to prevent crimping and bunching.

It’s been more than half a century since cosmonaut Alexei Leonov became the first human being to walk in space, and in all that time the work hasn’t gotten appreciably easier or even much safer. But it hasn’t gotten less transcendent either.“You can hear your heart beat and you can hear yourself breathe,” Leonov told photographer Marco Grob last spring in a story for Time. “Nothing else can accurately represent what it sounds like when a human being is in the middle of this abyss.”

Kelly and Lindgren, new to that abyss, will experience it soon.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com