A new study tracking teens and young adults finds that stealing is quite common: about 1 in 6 report having swiped something in the past year.

The study, published in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, found that for most of these young thieves stealing is just a temporary phase, likely because they decide the risks outweigh the benefits.

Geoffrey Fain Williams, an economist at Transylvania University, used data on self-reported thefts from Ohio State University’s National Longitudinal Study of Youth, which followed more than 8,000 people who were 12 to 16 years old when the survey launched in 1996. In the 15 years that followed, participants were asked about a variety of topics, including stealing. The subjects were regularly asked whether they had stolen something in the past year and if so, how much it was worth.

Williams found that theft is relatively common, with about 16% of the participants reporting having stolen something in the past year. One in 5 men have swiped something; 1 in 10 women report doing the same. But people generally only steal for a short period of time, with less than 5% continuing to steal for more than a year.

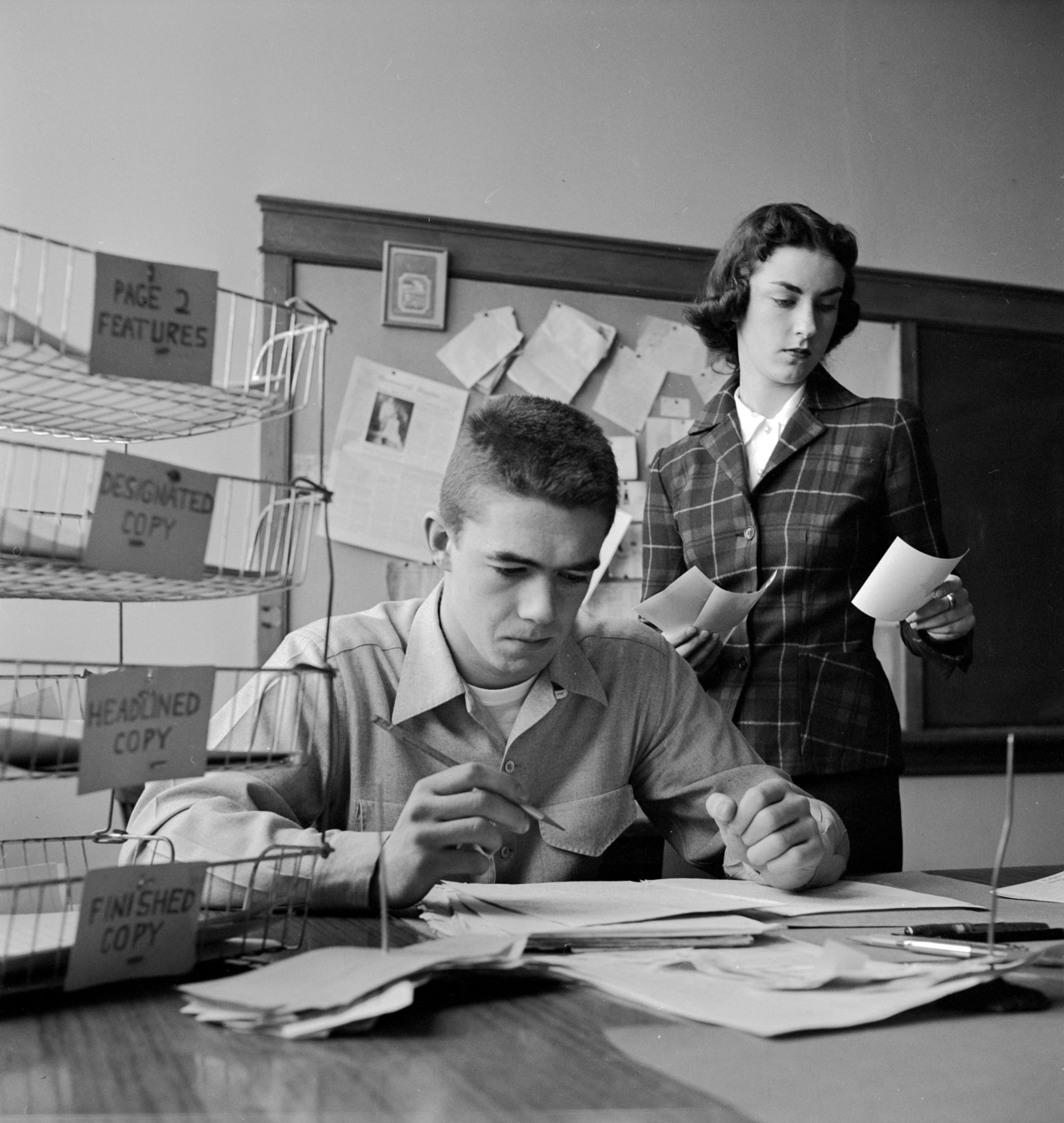

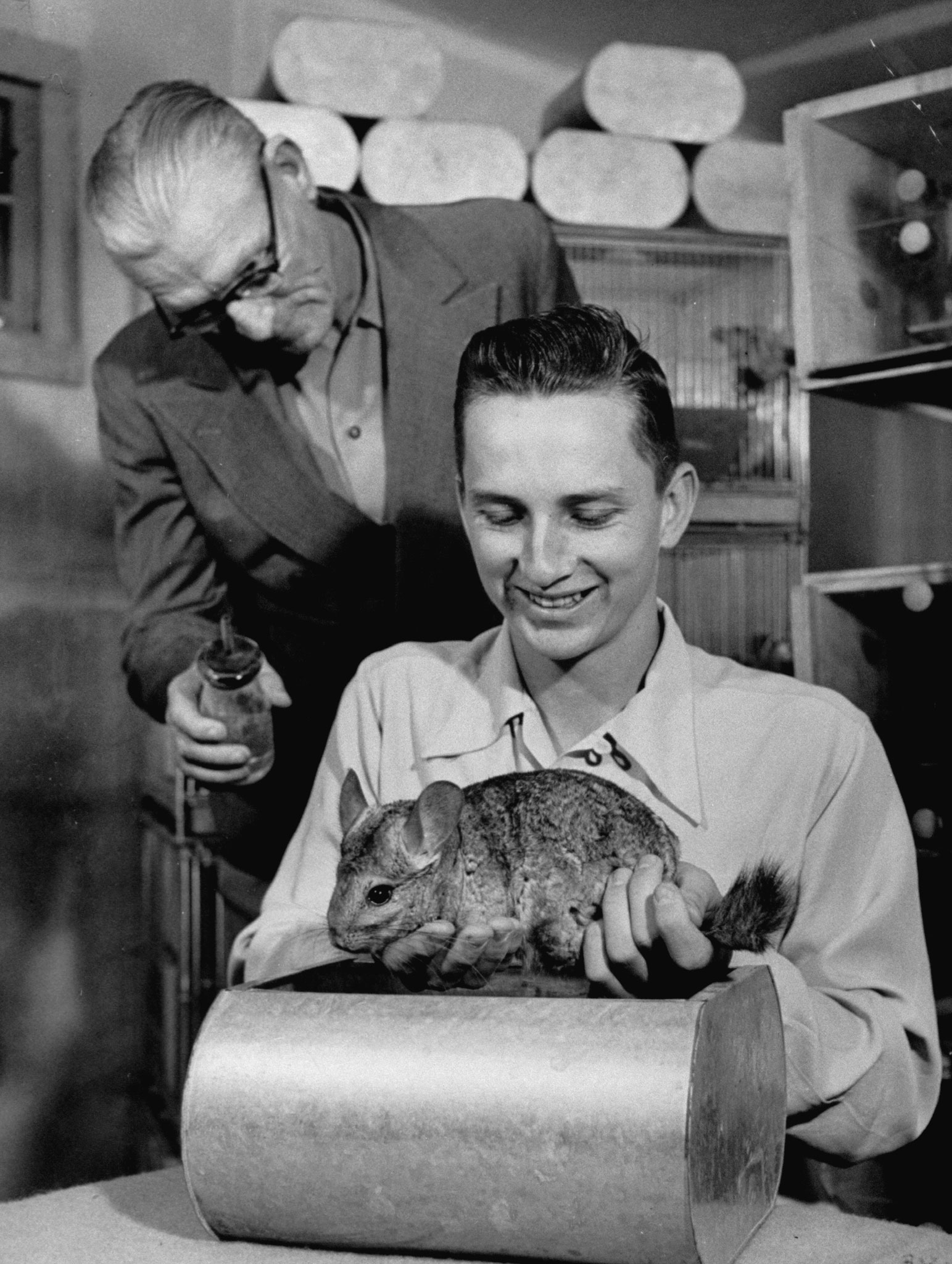

'The Luckiest Generation': LIFE With Teenagers in 1950s America

“For the majority of offenders, property crime may simply be an exploratory phase,” Williams wrote. Once offenders entered their late teen years, their interest in continuing to steal dropped off dramatically, with most thieves under the age of 24, the study found. One reason the young thieves may have lost interest is that they mostly stole objects of little value, only netting about $37.50 per theft. And the thieves generally didn’t need the money; most of the thieves were well off, and being poor didn’t drive the study participants to steal more.

One potential issue with the study is that stealing was self-reported, so actual numbers could be higher.

Next on Williams’ agenda is to examine the connection between stealing and instant gratification, including whether those who steal have trouble understanding the consequences and why they may lack self control.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Tanya Basu at tanya.basu@time.com