On Dec. 10, 1964, members of the Ku Klux Klan entered Frank Morris’ shoe repair shop in Ferriday, La., and set it on fire. They then doused him with gasoline and put a match to him as well. Morris ran down the street, screaming for help. The police took him to Concordia Hospital where he died four days later of third-degree burns. More than 50 years after his death, no one has been prosecuted for the murder of Frank Morris.

“You could not have met a better person than my grandfather,” says his granddaughter Rosa Morris Williams, now 63. “My grandfather was a very special person. He never did anything to anyone. He always tried to help people. It’s just so sad someone would take his life like that.”

Morris Williams was 12 years old at the time of her grandfather’s death. She recalls that, like many small Southern cities, Ferriday operated under a racially segregated Jim Crow system rife with violence and intimidation. Even if it had been known who was responsible for the heinous crime, people were afraid to talk for fear of getting killed themselves, she says.

But today is a different time. Now, Morris Williams is looking for justice: “If someone did wrong, they should be able to give account of their wrongness,” she says. “That’s all I would want.”

So, in 2007, she began working with Syracuse law professors Paula Johnson and Janis McDonald to help find her grandfather’s killers. The two attorneys soon realized that the case was not unique.

“We realized during that process that nobody had ever done a full accounting of all the people who disappeared or were killed,” says McDonald.

As a result, the two established the Cold Case Justice Initiative (CCJI) at Syracuse University. The CCJI investigates racially motivated murders that occurred during the Civil Rights era and advocates on behalf of the victims and their families to get justice for the crimes. The program works with law students to conduct research, identify victims and find new information that could assist law enforcement in resolving cases. The CCJI has identified 196 cases from the civil rights era they believe warranted further investigation by federal authorities. And, for a time, it seemed like they might get their wish: that same year, Rep. John Lewis of Georgia introduced the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of 2007.

“I introduced the [Emmett Till Act] because there are hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of cold cases from the civil rights era that have never been solved,” Lewis told TIME.com in an email. “Men and women disappeared never to be heard from again. People were lynched and left hanging. Some bodies were burned beyond recognition. These are acts that must be answered by our society. Many of the people who are aware of the circumstances surrounding these deaths are passing away, and most local police departments do not have the capability to investigate these cases.”

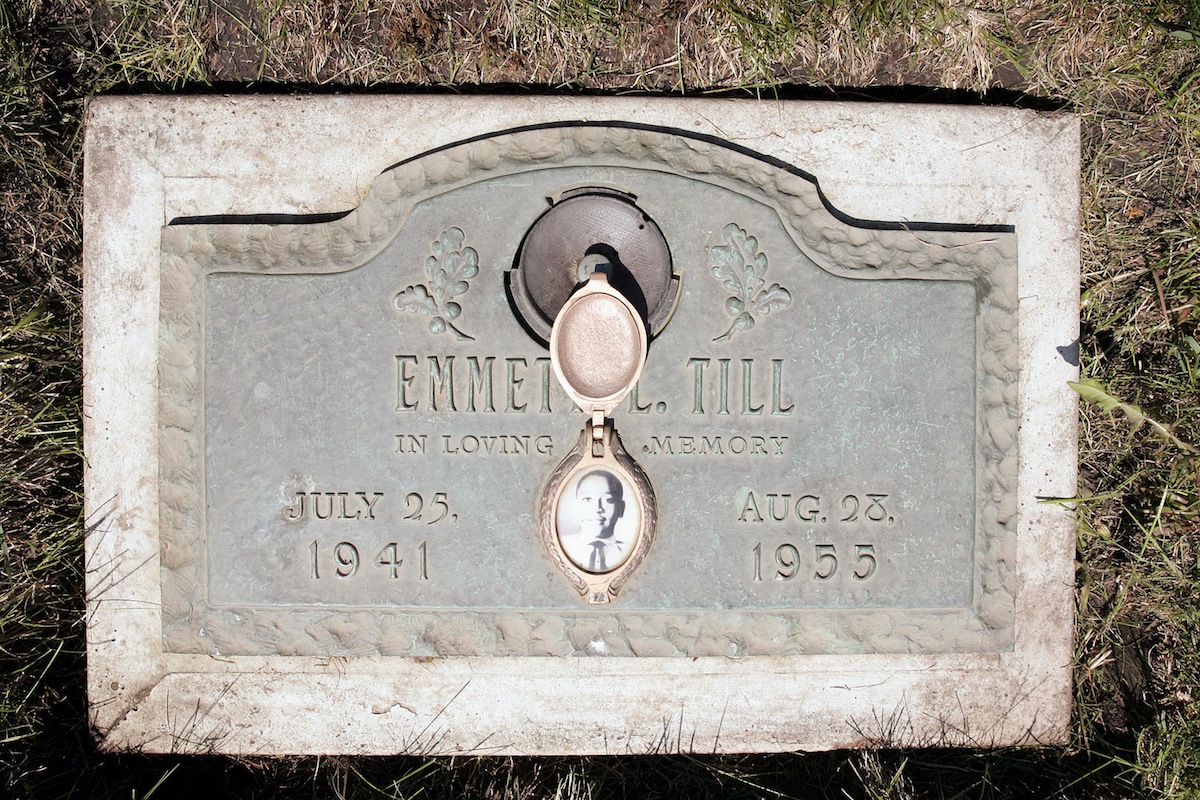

The act was named after the 14-year-old Chicago teen who was brutally lynched in 1955 for allegedly whistling at a white woman in Money, Miss. Till’s killers, J.W. Milan and Roy Bryant, were acquitted by an all-white male jury. They later confessed to the crime in Look magazine, but no one has ever been convicted of the teen’s murder. The legislation, which requires the U.S. Attorney General to appoint a team to investigate and prosecute unresolved civil rights murders that occurred before 1970, was unanimously passed by both chambers and signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2008.

“Families have suffered in silence, waiting for our society to live up to the call of equal justice,” Lewis notes. “We need to do all we can, even 40 or 50 years later, to respond to these tragedies.”

Now, however, that law is nearing its expiration, which will arrive in 2017 if an extension is not added—even though, since the act was signed into law seven years ago, there has only been one successful state prosecution. In a report to Congress that was presented in May of this year, the Department of Justice acknowledge that, although it had concluded 105 of 113 relevant cold cases involving 126 victims, “very few prosecutions have resulted from these exhaustive efforts.” (The single case that went to court involved Jimmie Lee Jackson, who was shot by Alabama State Trooper James Fowler after a civil rights protest in 1965. In 2010, at age 77, Fowler pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to six months in prison.)

So, while CCJI is calling on Congress to amend the existing legislation so that it doesn’t run out in two years, the organization also wants Congress to hold the FBI and Justice Department more accountable to the mandate, preferably with public hearings. CCJI and its law students have traveled to Washington to talk to members of Congress “about the need for them to exercise their congressional oversight over such a critical statute that they passed,” says Johnson. “It’s not enough to just pass a statute and then not inquire to how it’s being implemented.”

The CCJI has also traveled to Geneva and visited the United Nations to plead its case, hoping that international pressure might move the dial. After all, McDonald adds, advocates can ask questions but only Congress can demand the answers.

Not that anyone thinks getting those answers will be easy: The DOJ report on progress made under the law detailed the challenges the agencies faced investigating 50-year-old cases. For example, it pointed to federal statutory law that limits the Justice Department’s ability to prosecute civil-rights era cases at the federal level and a five-year statute of limitations on federal criminal civil-rights charges that existed prior to 1994. Then there’s the Fifth Amendment protection against double jeopardy, which prevents the re-trial of someone for an offense for which he was previously found not guilty.

The Department of Justice admitted in its report, “Even with our best efforts, investigations into historic cases are exceptionally difficult, and rarely will justice be reached inside of a courtroom.” In addition, cold cases can be difficult to prosecute, the report noted because, “subjects die, witnesses die or can no longer be located, memories become clouded, evidence is destroyed or cannot be located.”

CCJI’s leaders argue that the difficulty involved only means these cases must be pursued with greater speed and dedication than ever. The Frank Morris case shows why: a suspect was identified but died before a grand jury could issue an indictment.

“We think that that’s an instance where the Department of Justice and the FBI didn’t act thoroughly or quickly in order to bring those folks to justice,” said Johnson. “There were people out there who had information, people who had even made admissions and had that been treated with more swiftness and commitment by the Department of Justice we think that something would have come of that.”

Then there’s the case of Joseph Edwards of Louisiana, who disappeared in 1967. His car was found with a noose and drops of blood inside. His body was never found. Using the Freedom of Information Act, CCJI found 6,000 to 8,000 un-redacted FBI files at the National Archives on Joseph Edwards. McDonald adds that they found notes on the documents, from all the way back in 1968, indicating that the investigators had asked for the case not to be closed as there was a viable possibility for prosecution at the time. Despite CCJI handing over those documents to the Justice Department and FBI, the agencies closed the case.

In its notice to close the file on Joseph Edwards, the Department of Justice noted that “the FBI interviewed in excess of 250 witnesses and conducted multiple scuba searches and forensic tests, resulting in a case file of about 620 pages.” It also noted that attorneys reviewed the results of a 2010 investigation and numerous newspaper articles. The notice points out that the “FBI conducted an extensive investigation into numerous theories” and concluded that the “majority of those theories were not supported by sufficient credible or corroborated evidence, and the investigation did not produce any solid leads.”

In an email statement to TIME.com, a Justice Department spokesperson further explained why a case like Edwards’ might be closed, despite what looks like a good lead. The Department can’t prosecute without solid evidence—and even if evidence does exist, the case will be closed if it’s judged not to be enough to establish guilt beyond a reasonable doubt: “This is true regardless of whether the matter is current matter or whether it occurred 50 years ago. As the Department’s annual reports on the Emmett Till Act clearly show, the inherent impediments to procuring available, reliable, and admissible evidence in a case that is decades old substantially limits our ability to secure justice through a criminal prosecution.”

In its latest report to Congress, the Department of Justice concluded that, “it is unlikely that any of the remaining cases will be prosecuted.”

Realistically, it seems that the era for solving the civil-rights crimes of the ‘50s and ‘60s is drawing to a close. But, despite that and despite the Department of Justice’s detailed report on its investigation, CCJI is still calling for a special task force familiar with the civil-rights era to independently examine the crimes.

“They are still looking for and prosecuting people who had any role in the Holocaust. There was just a prosecution recently of a guard who had a role in those atrocities. So why should there be a limit on these cases?” asks Johnson. “This work just needs to continue. It’s as simple as that, because we have only touched the surface, the tip of the killings that happened in this era and beyond.”

She believes it’s worth the effort. After all, every potential prosecution is not only a chance for the criminals to be held accountable, but also for society at large to learn what happened during a period that remains difficult to confront.

Rep. Lewis acknowledges that the Emmett Till bill has never been fully funded or “completely executed,” and that Congress is considering extending the act. The Congressman notes that the attempt to prosecute the criminals of the civil-rights era could be an important way for families and society as a whole to get closure. But, for now, the DOJ is looking for closure in a different way. The Department wrote letters to the next of kin of victims and had FBI agents hand-deliver the letters. The agency was able to find family members for 102 of the 126 victims from 113 cases.

It was a few years ago that an FBI agent visited the home of Rosa Morris Williams and delivered her just such a letter. It said that her grandfather’s murder case had been closed. In its notice to close the file, the FBI explained that it “was unable to conclusively determine who committed the crime and the most likely suspects are all deceased.”

But Morris Williams hasn’t given up hope.

“Somebody might still be living who want to confess and say ‘Well, I was involved,’” she says. “I still believe in my heart that there will be justice. I don’t ever doubt that.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com