Belarusian writer Svetlana Alexievich received the 2015 Nobel Prize for literature on Thursday. She is the 14th woman out of the 111 winners in the prize’s history. In other words, almost 90% of awardees have been men. Despite this much deserved-award, our culture continues to cultivate a preference for narratives about and by men.

Why does it matter? Pervasive, global, cultural biases favoring men’s language, opinions, experiences and authority have created a dangerous epistemological distortion in our understanding of what it means to be human. It matters because ignoring women’s stories, words and experiences dehumanizes all of us. It is deeply complicit in widespread gendered violence and injustice.

Today, still, simply having a man’s name often means that a writer’s work will be considered more seriously—by publishers, readers, critics and award committees. Earlier this year, novelist Catherine Nichols, replicating the format of countless implicit bias studies, changed her name to a man’s and resubmitted her manuscript to multiple publishers. “George” received more responses than Catherine. Nichols’ experiment is depressing, but not surprising. J.K. Rowling, among the most notable women to have gender-neutralized their names, is part of a very long tradition that includes the Bronte sisters (aka, the Bell Brothers), Louisa May Alcott (B.A. Evans), Amantine-Lucile-Aurore Dupin (George Sand), Susan Eloise Hinton (S. E. Hinton), Harper Lee (Nelle Harper Lee), Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot), Robyn Thurman (Rob Thurman) and Alice Bradley Sheldon (James Tiptree).

Greater confidence and interest in men’s voices extends to the subject of stories. Earlier this year, writer Nicola Griffith conducted an analysis of the past 15 years of Pulitzer, Man Booker, National Book, National Book Critics’ Circle, Hugo and Newbery medal awards. Her research revealed not only that men are far more likely to win, but that even books with male protagonists are preferred. The Pulitzer Prize results were particularly arresting: None of the 15 winners were told wholly from the point of view of a woman or girl. In the least prestigious area, young adult fiction, criticized for not being serious fiction, girl protagonists fared better.

The obstacles women face being taken seriously as people whose words and experiences and opinions matter were neatly summarized in 1978 by Joanna Russ, in her slim and elegant book How to Suppress Women’s Writing. As she put it: “She didn’t write it. She wrote it but she wrote only one of it. She wrote it, but she isn’t really an artist, and it isn’t really art, She wrote it, but she’s an anomaly. She wrote it, but it’s irrelevant.”

This issue isn’t a “war of the sexes” or a “men bad” problem. All of us have these implicit biases. But there is a marked gender asymmetry that speaks to the fact that dominant groups often have no need or desire to understand the dominated. Whereas women will read writers of either sex, many men resist reading books by women. This is unsurprising given how early girls and boys are exposed to a gross majority, in almost any medium, of male-centered voices and are expected to emphasize with both genders.

This imbalance illustrates a compounded and negative social effect: Literary fiction remains dominated by male voices, but mostly read by women, who benefit from their consumption. People who read literary fiction have a better-developed sense of complex social interactions, or what social scientists call Theory of Mind. They do better on tests for empathy, social perception and emotional intelligence.

Left largely unchallenged, however, the bias for male voices continues to reproduce itself in the imaginations of children. White, male characters make up the majority of subjects of children’s books, games and television programing, even when women are writing. One analysis of children’s TV programming showed that all children, with the exception of young white boys, are left with degraded self-esteem after watching television.

Implicated in this problem, substantively, are schools. For example, I recently reviewed the course work for a 10th grade English class at a local high school. It included six books about men, one written by a woman. Among them was A Man for All Seasons, or, as one student, a 15-year old girl, put it, “A Woman for None.” The theme for the class’ first semester, replete with generic male universals, is “Man’s treatment of other men.” Of the books being read, none features a primary female heroine.

Ignorance is the primary result of this millennia-old ghettoization of women’s stories. Women’s epistemologies and experiences still remain, in the mass cultural sense, stigmatized. All you have to do is sit through a presidential debate where candidates can barely name a prominent woman historical figure, or a legislative debate where government representatives make brazenly false and ignorant statements about women’s anatomy, health care, autonomy and lack of moral authority.

“Who we read affects the way we see the world,” explains Kayla E. publisher of Nat. Brut, a biannual art and literary journal that aims to rebuild the fields of art, literature, and comics as inclusive spaces. “Audiences who mainly consume the white, male narratives that dominate these arts seem to have difficulty empathizing with writers and characters whose narratives are different. Focusing on voices and stories that are traditionally pushed to the margins or completely left out of mainstream art and literary culture allows us to addressing this empathic disparity.”

Individuals’ empathy, or lack thereof, is a critical issue in terms of media diversity. But the problem of perspective and empathy are even more important in terms of collective social justice. In her slim and elegant treatise, Epistemic Injustice, philosopher Miranda Fricker explains the “negative space” of epistemic injustice as the “wrong done to someone specifically in their capacity as a knower.”

Globally, women are often in this position—our human bodies, human experiences, human needs and human rights are routinely ignored, belittled or misunderstood. So much of our experiences remain shrouded in shame and silence, that they are incomprehensible, even to the people experiencing them. Sexual harassment, menstruation, intimate partner violence, rape, menopause, early marriage, compulsory pregnancy, post-partum depression, and gendered experiences of racism and religious intolerance are examples of parts of women’s lives that, apparently, many men with public authority, continue to not either have knowledge or understanding of, or empathy for.

Alexievich’s Nobel could be interpreted by some as a sign that women not only have equal access, influence and recognition, but that boys and men suffer because of it. However, this assumption, a common one, also illustrates the problem. Studies show that when women speak as little as 30% of the time in mixed gender settings where they are outnumbered by men, everyone thinks they dominate. When they make up as little of 17% of crowds, visual bias results in people thinking the gender split is 50/50. As one student explained to me earlier this year, “Feminists go too far. There is such an imbalance in favor of women today.”

While it is no one’s fault that this is the situation we find ourselves in, literary and media institutions have to do more to understand the problem of homogeneity and male dominance as an ethical and moral failure. The Internet has undoubtedly shifted the playing field, enabling women to share stories long suppressed in culture. For example, the subject matter of 12 projects recently complied by Nat. Brut. proliferate stories about these and other, similarly women-centric topics. The telling of these stories is creating social understanding and allowing people to make sense of their shared experiences in ways that they haven’t historically been able to.

Diversifying media is not a superficial exercise, a job expansion project, or a “politically correct” way to unfairly slant the professional playing field. It is the promise of a more just society.

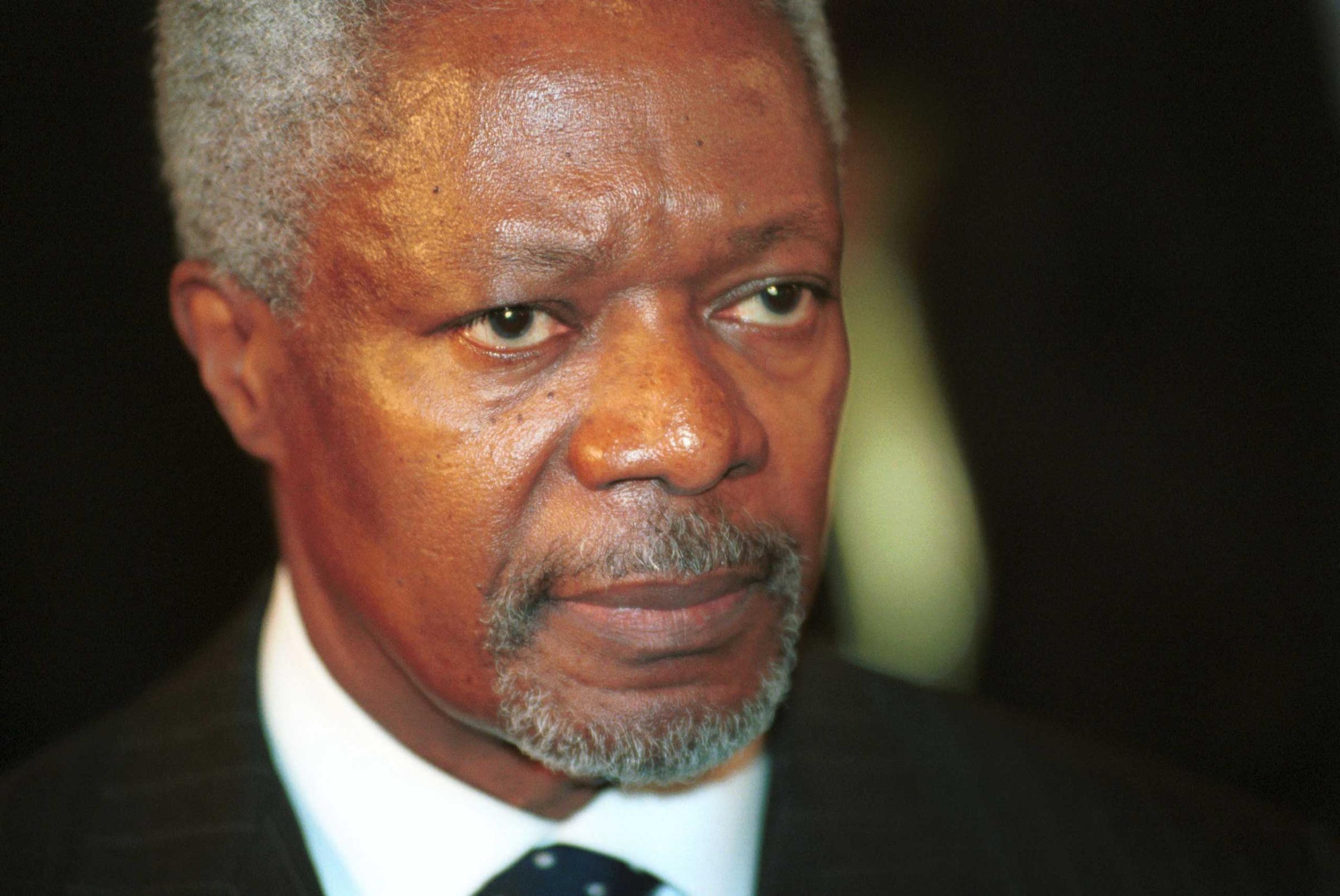

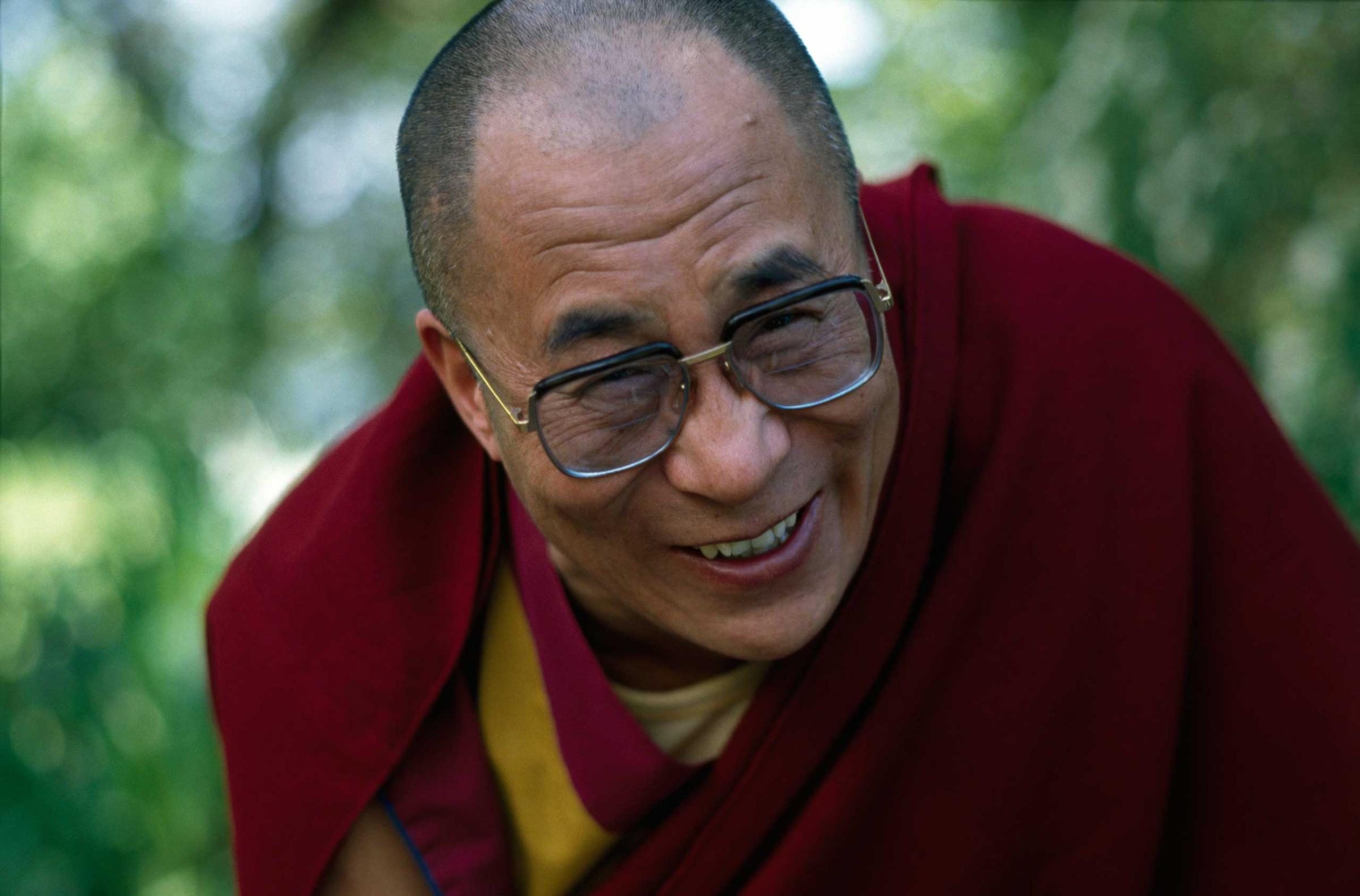

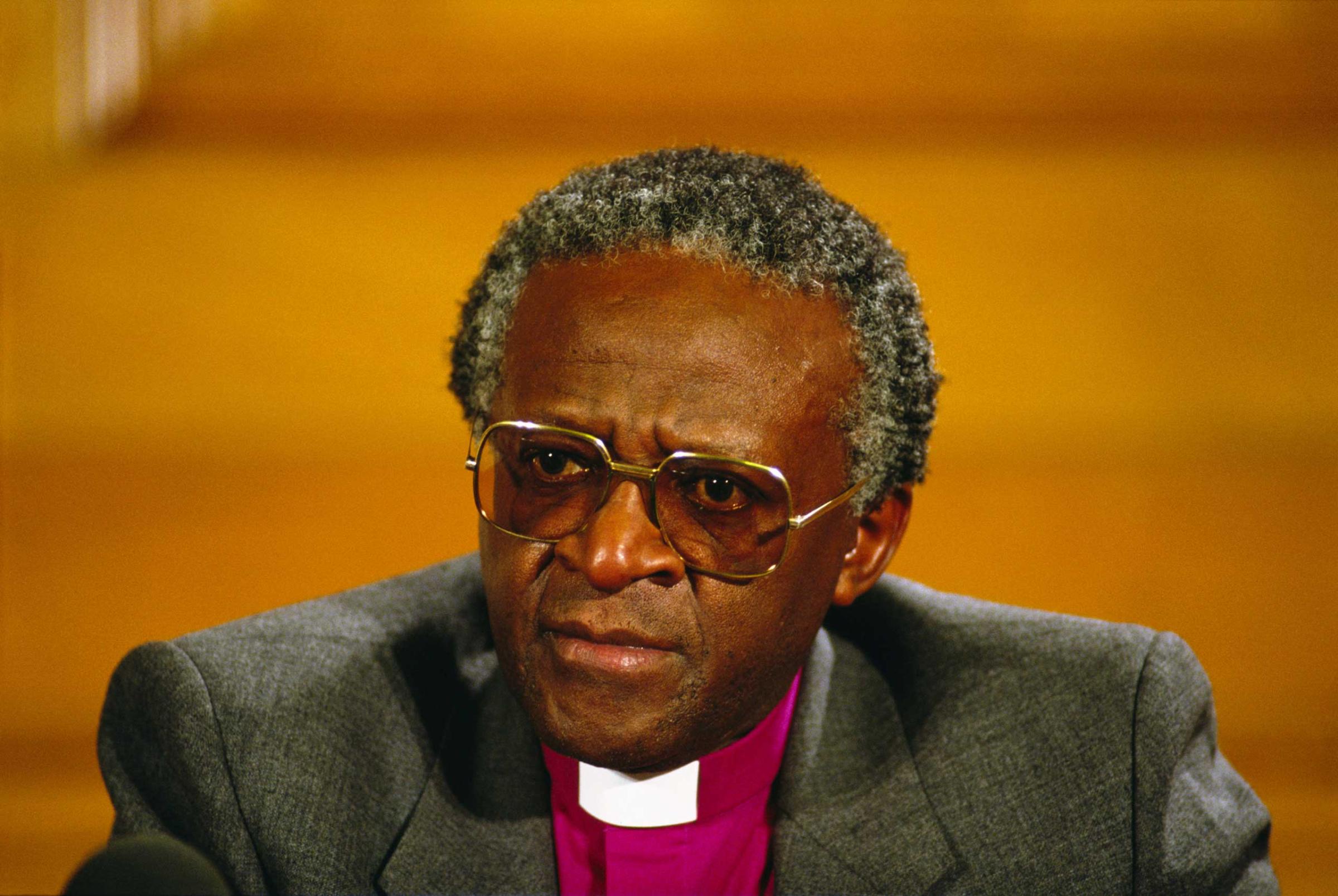

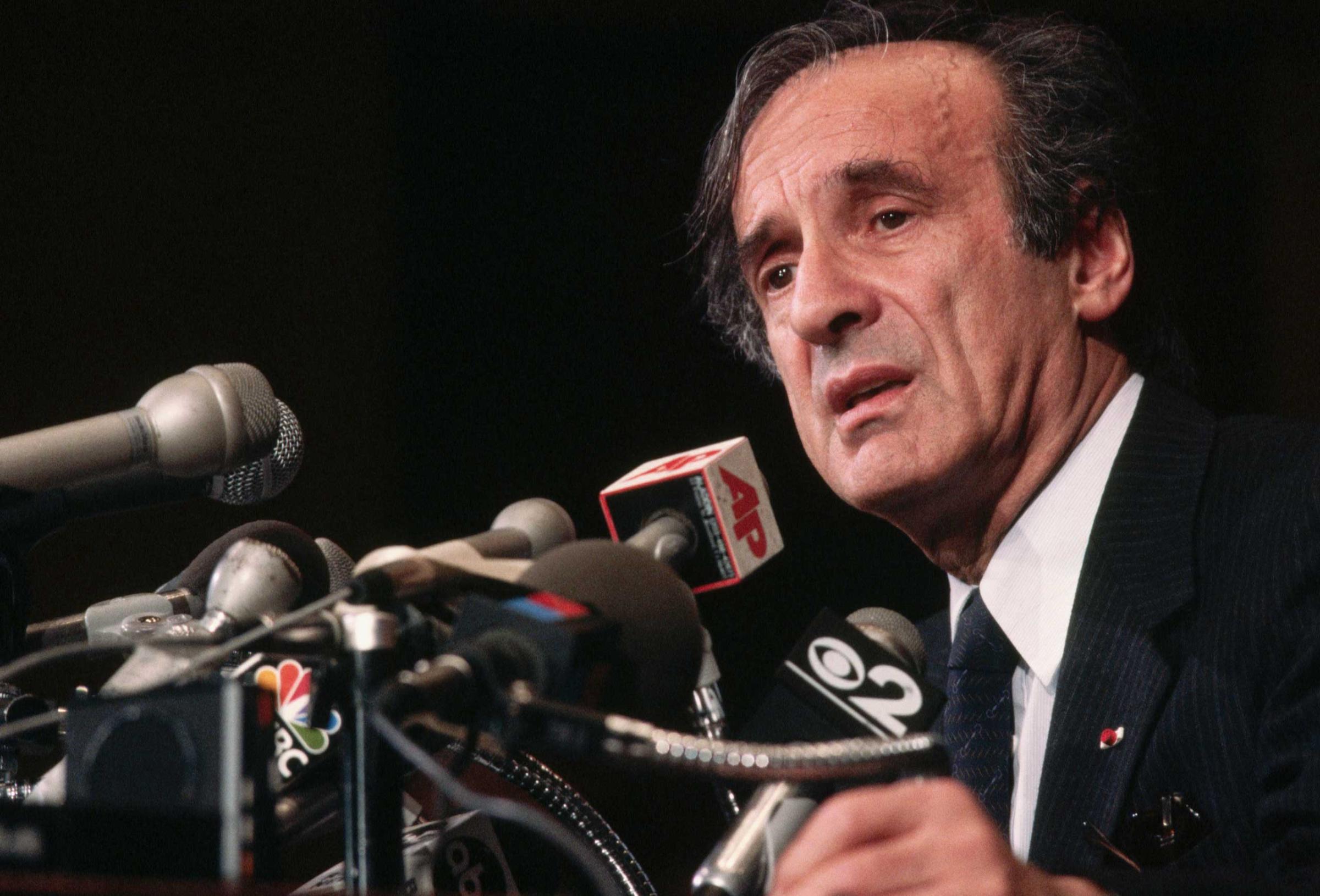

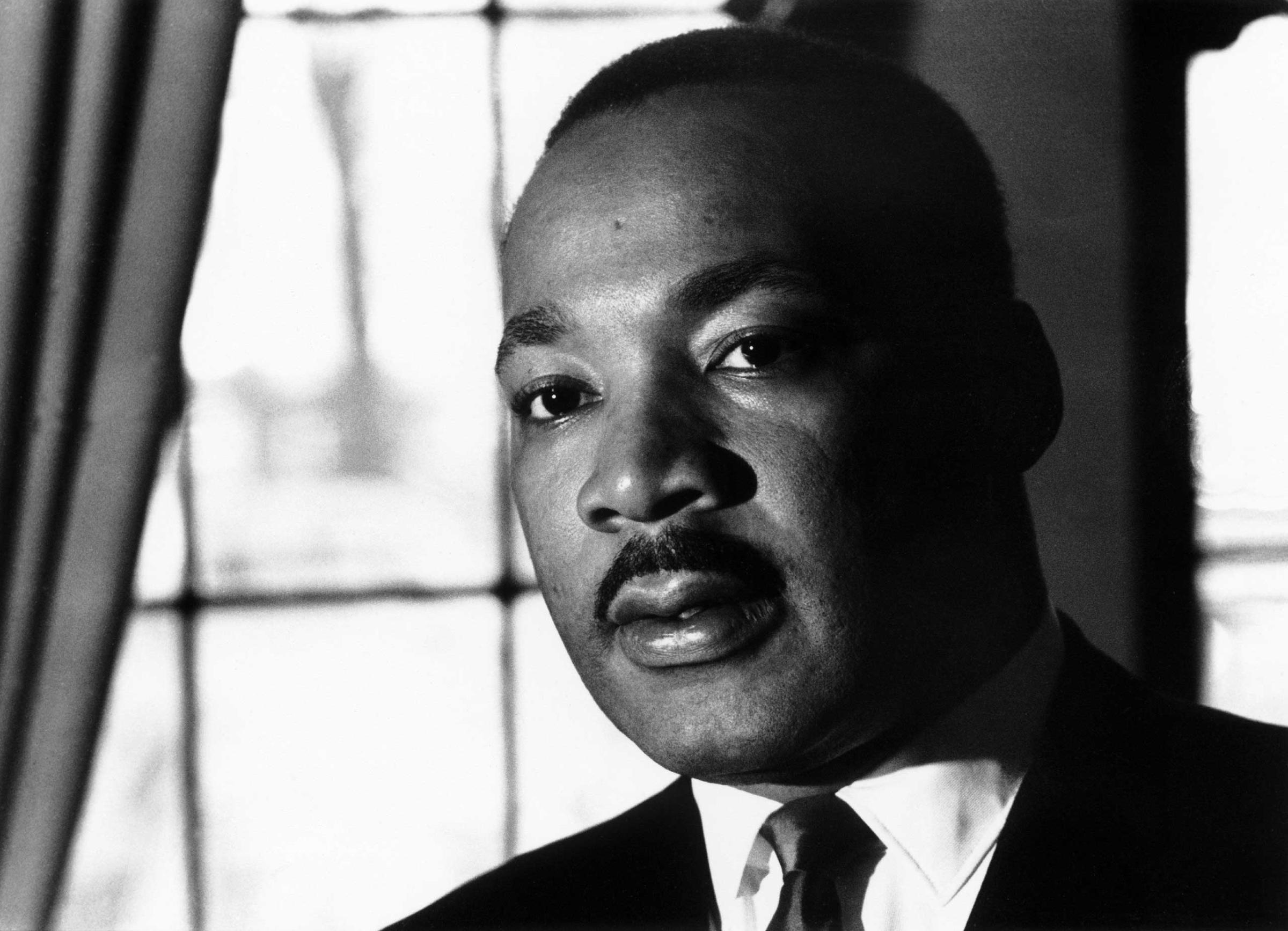

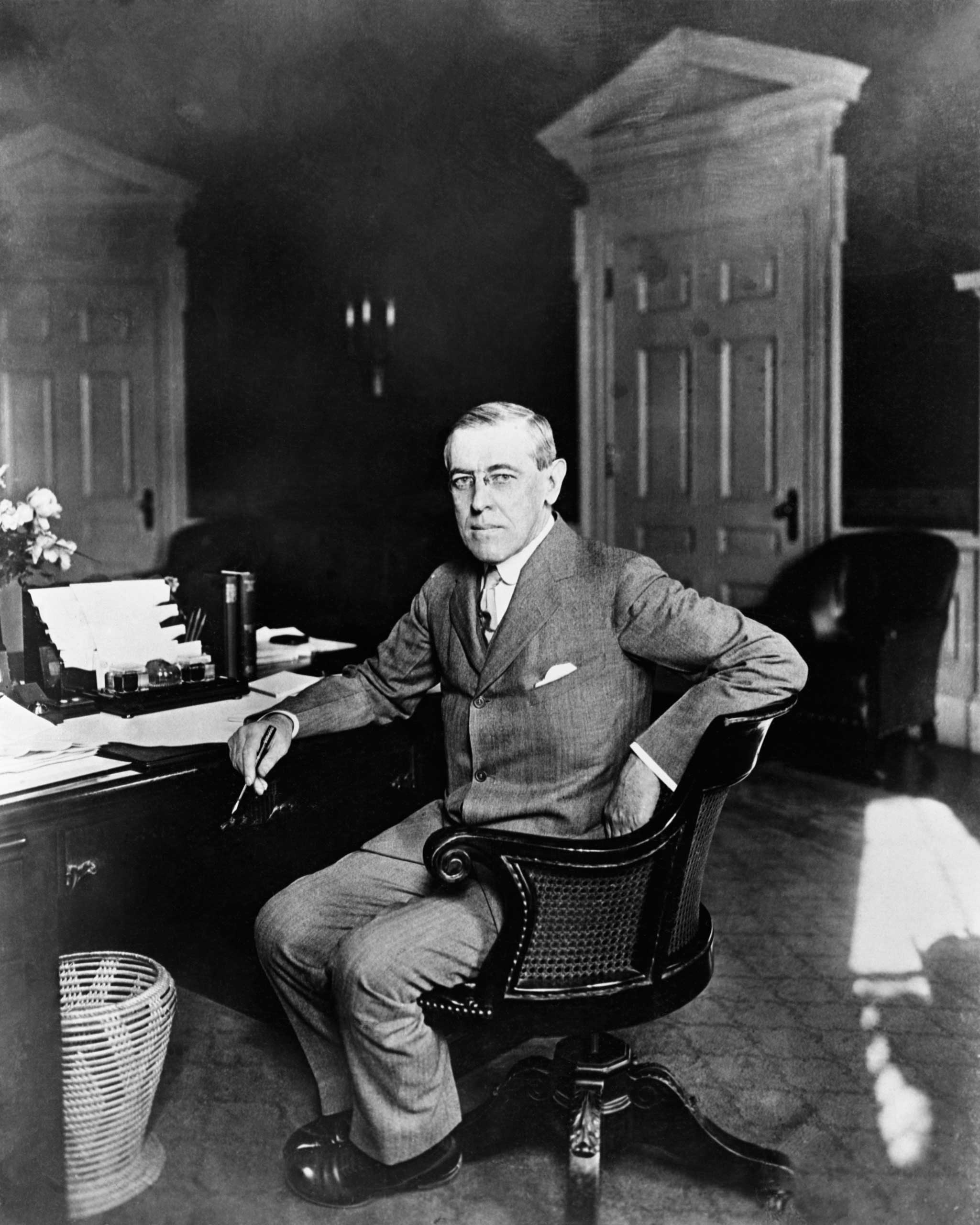

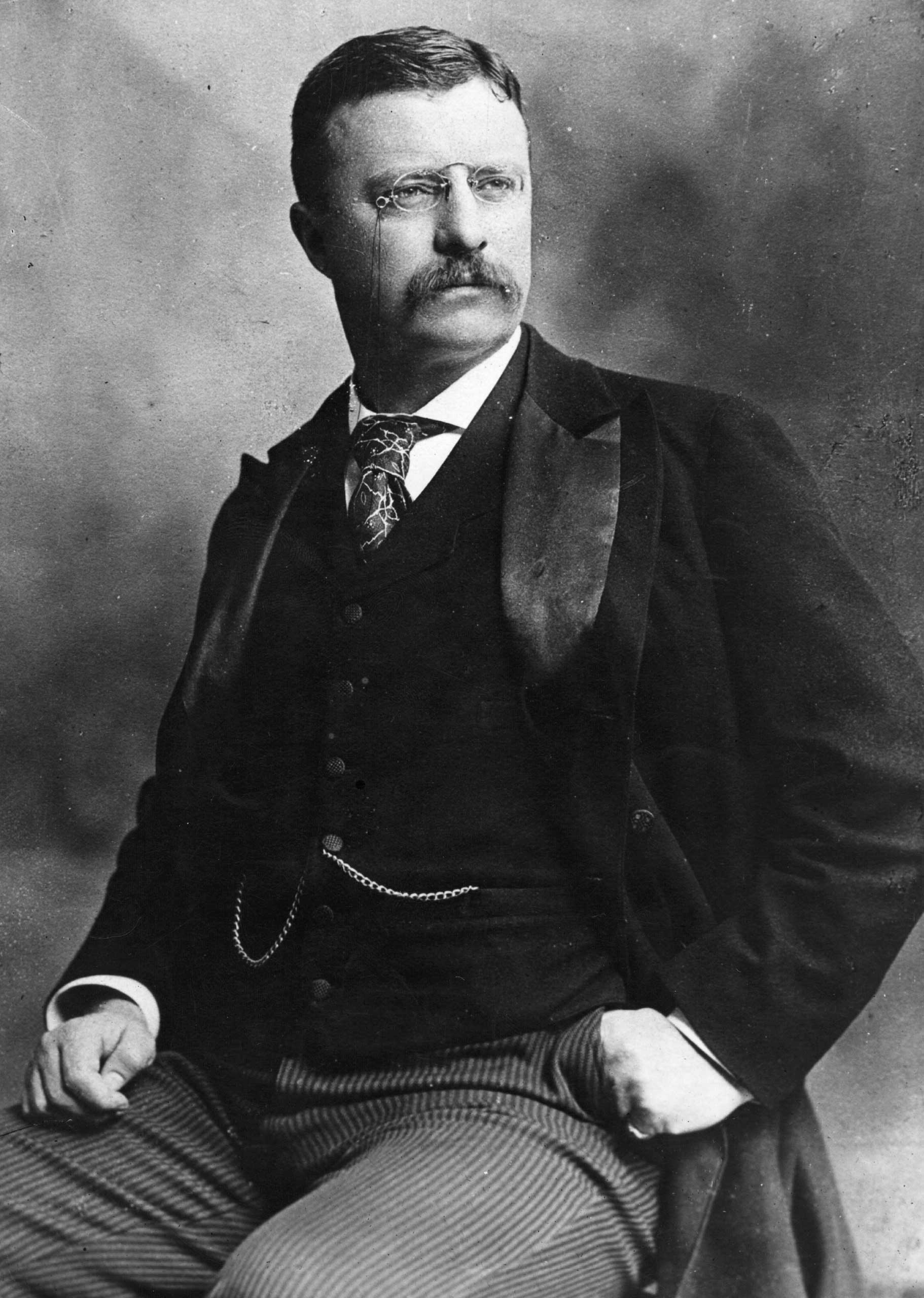

See the 20 Most Famous Nobel Peace Prize Laureates

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com