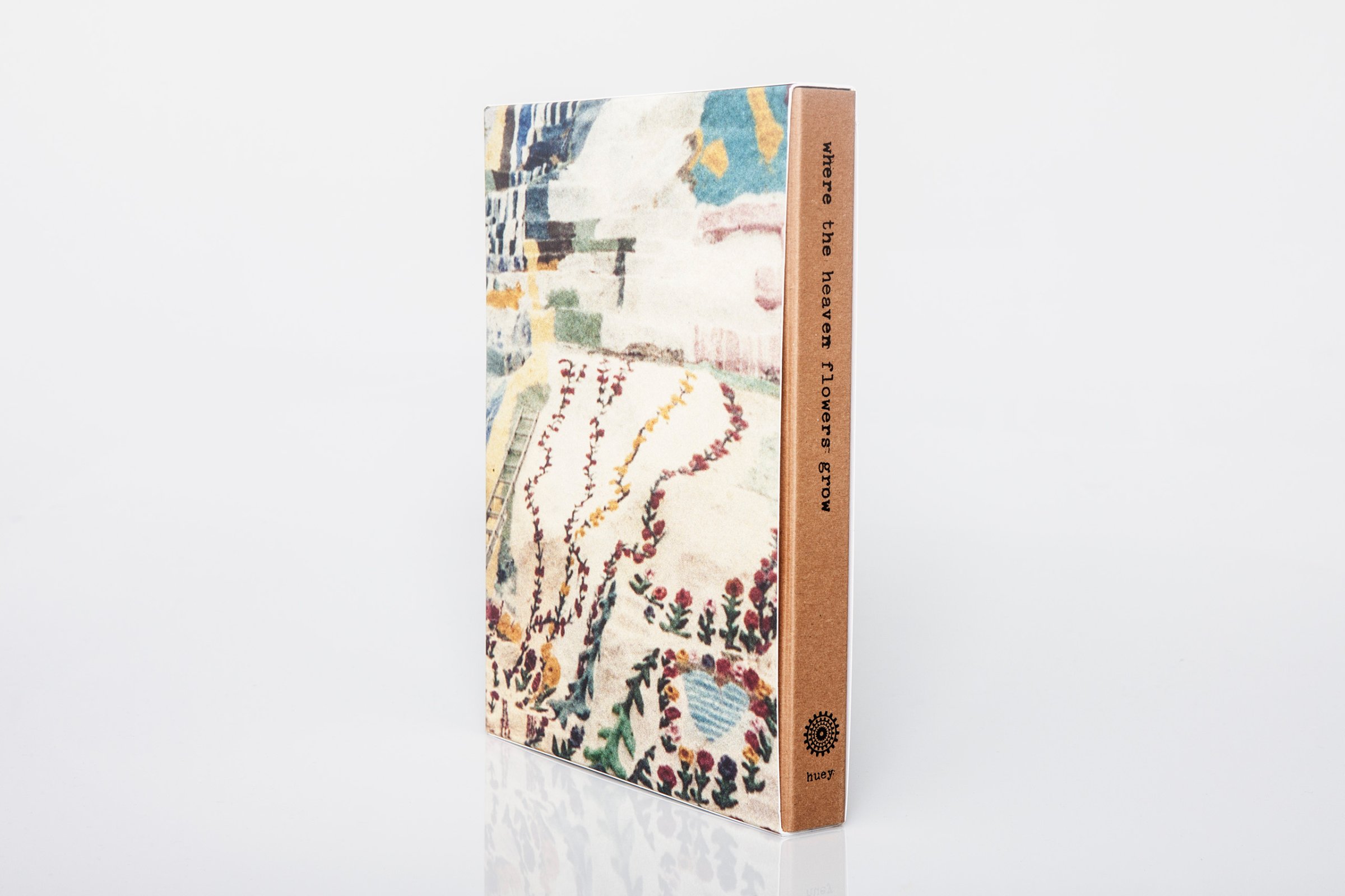

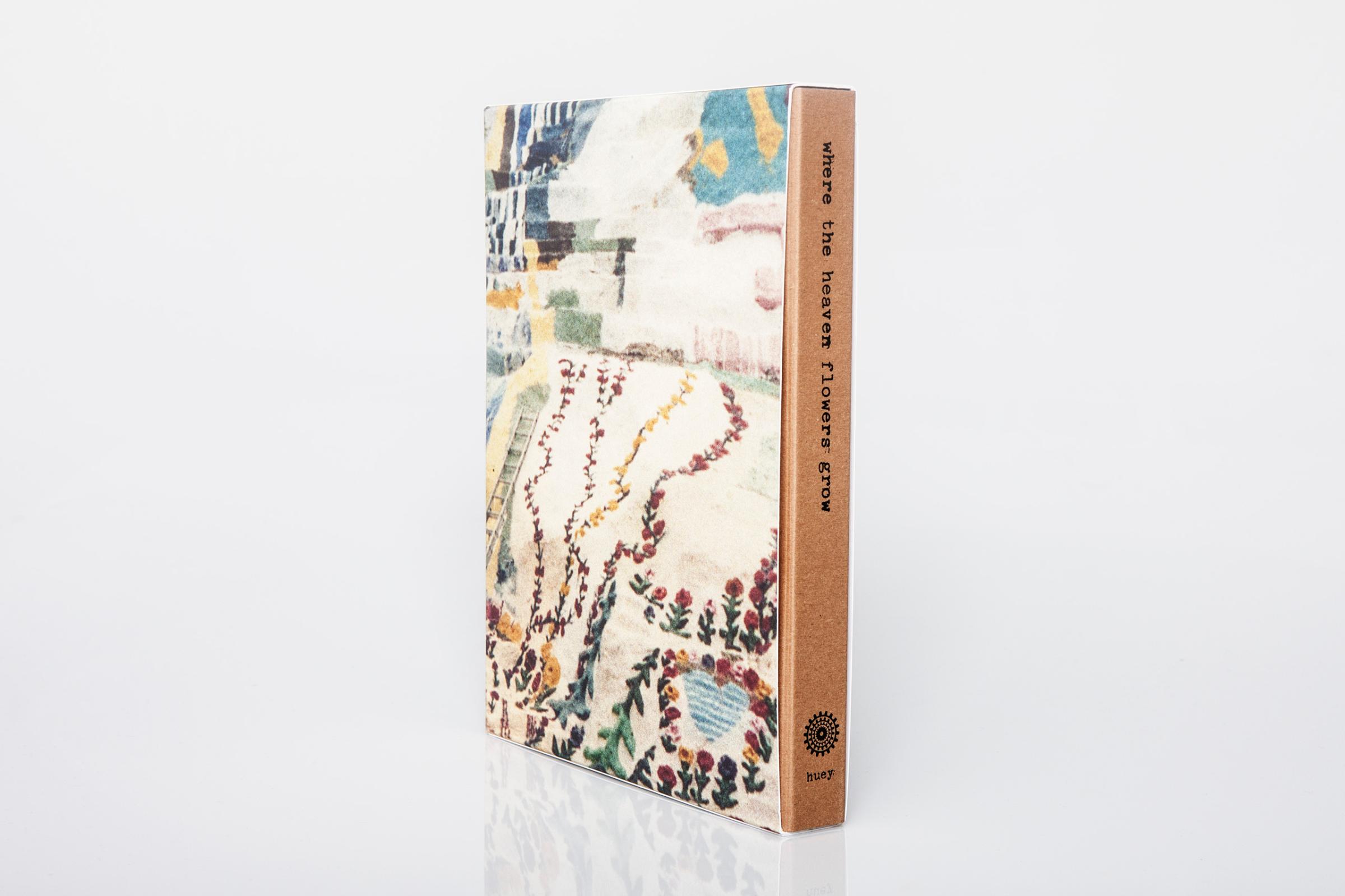

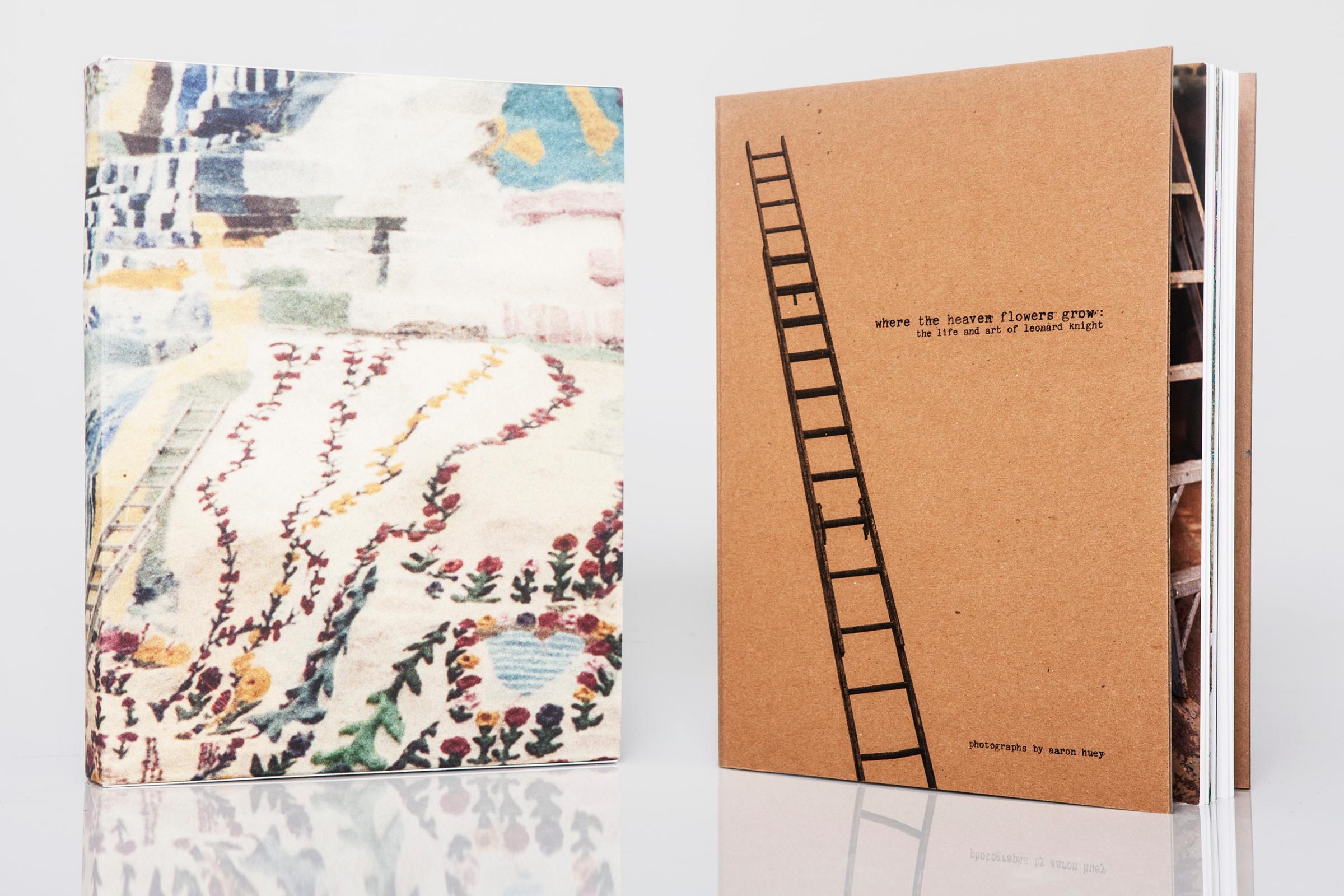

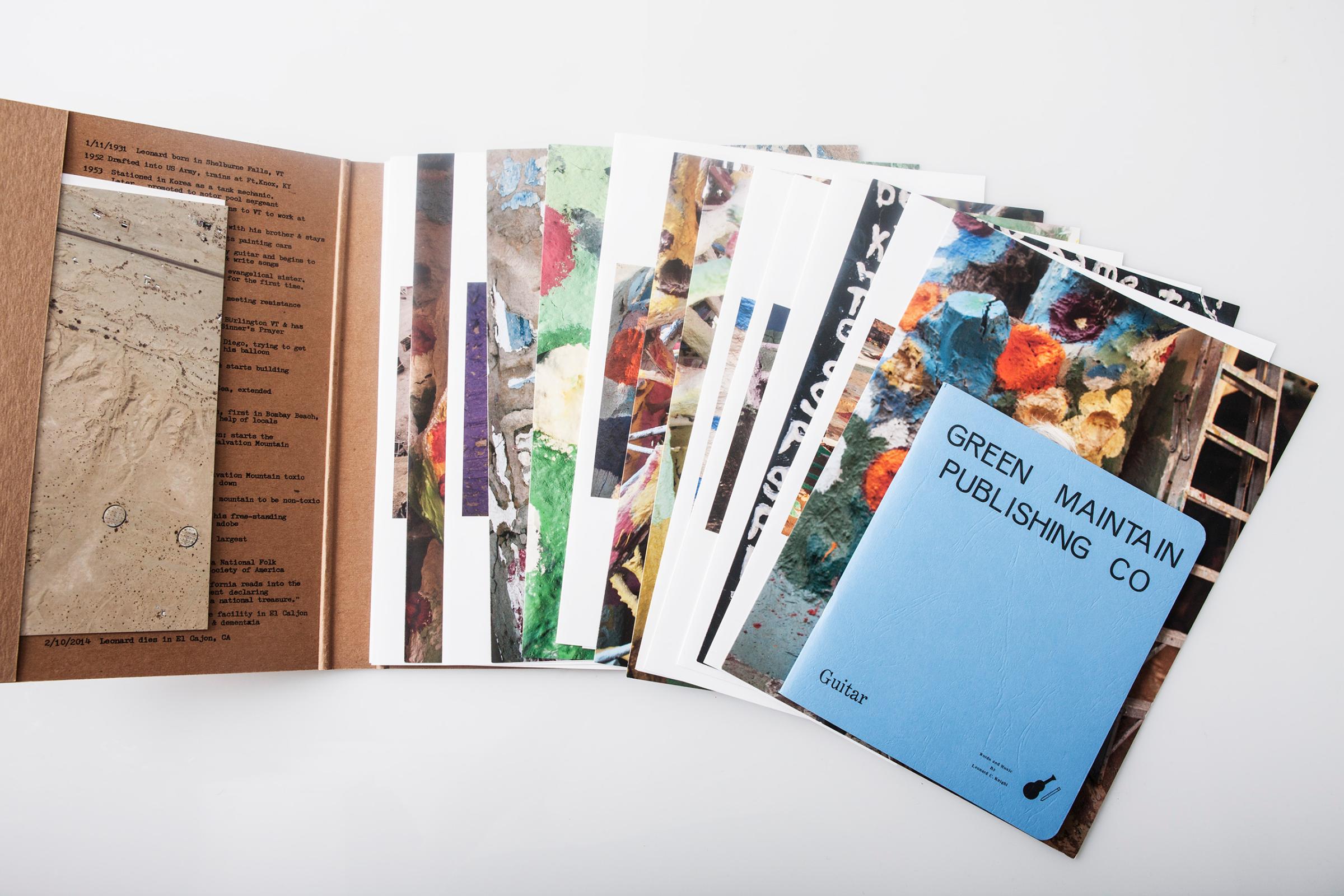

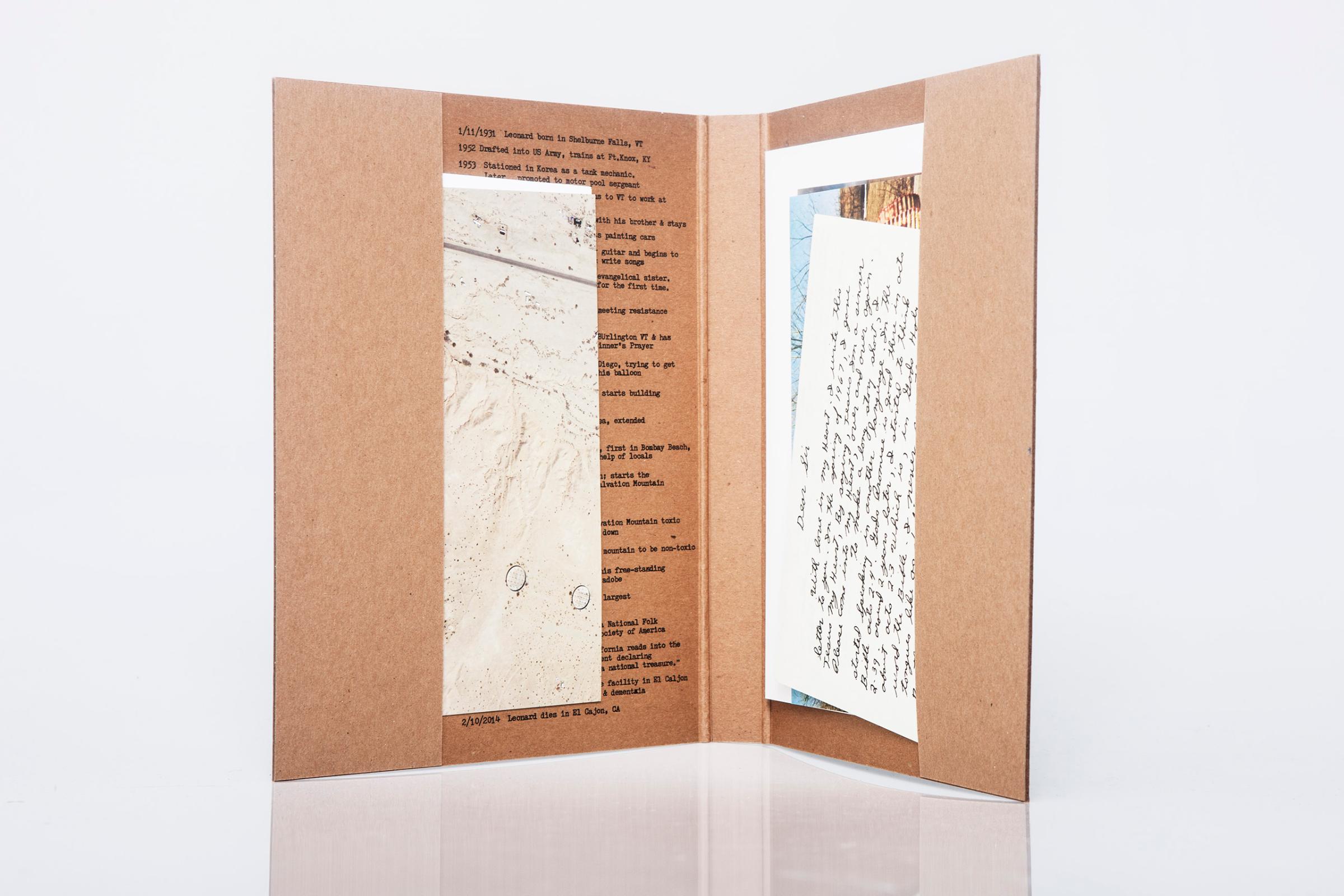

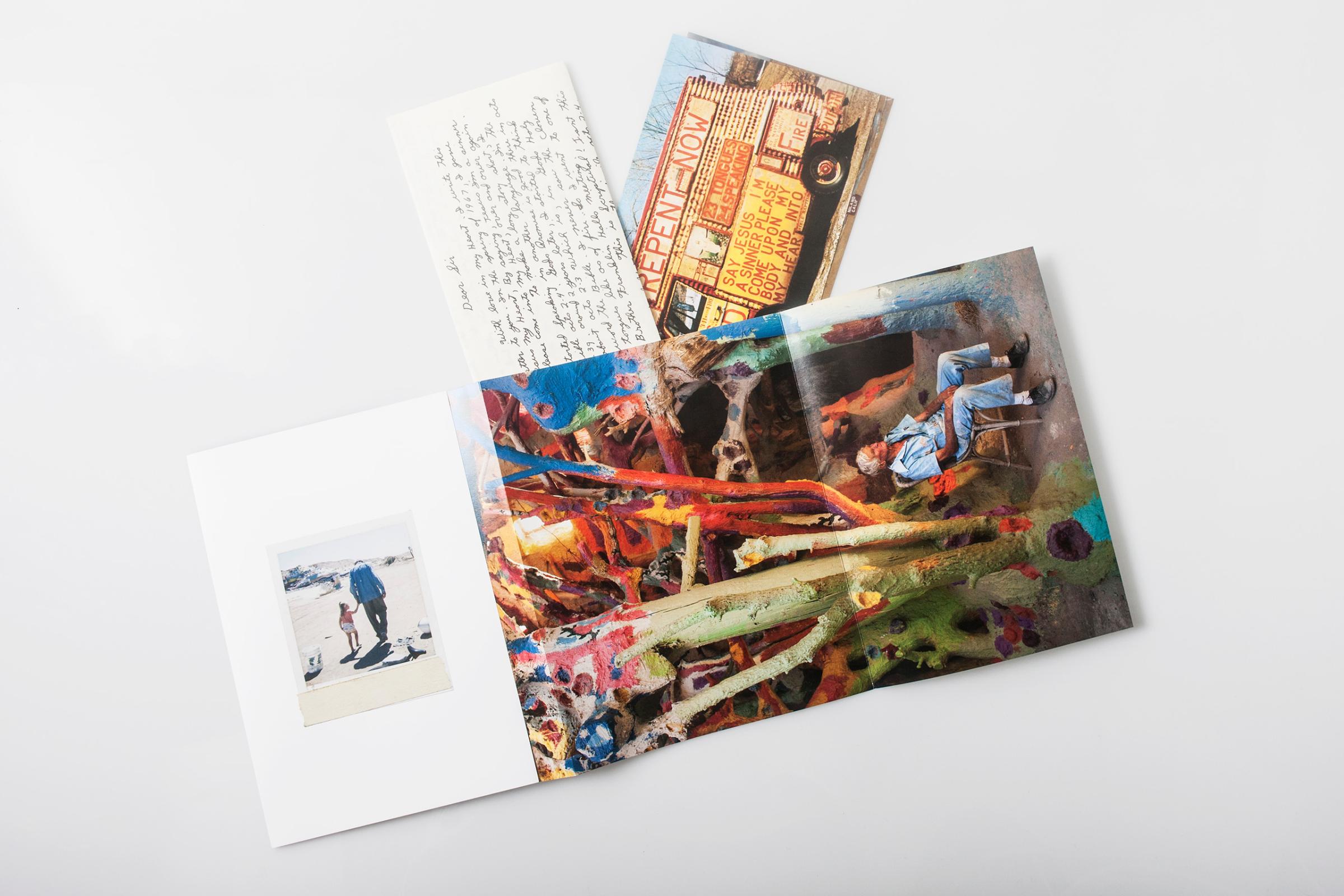

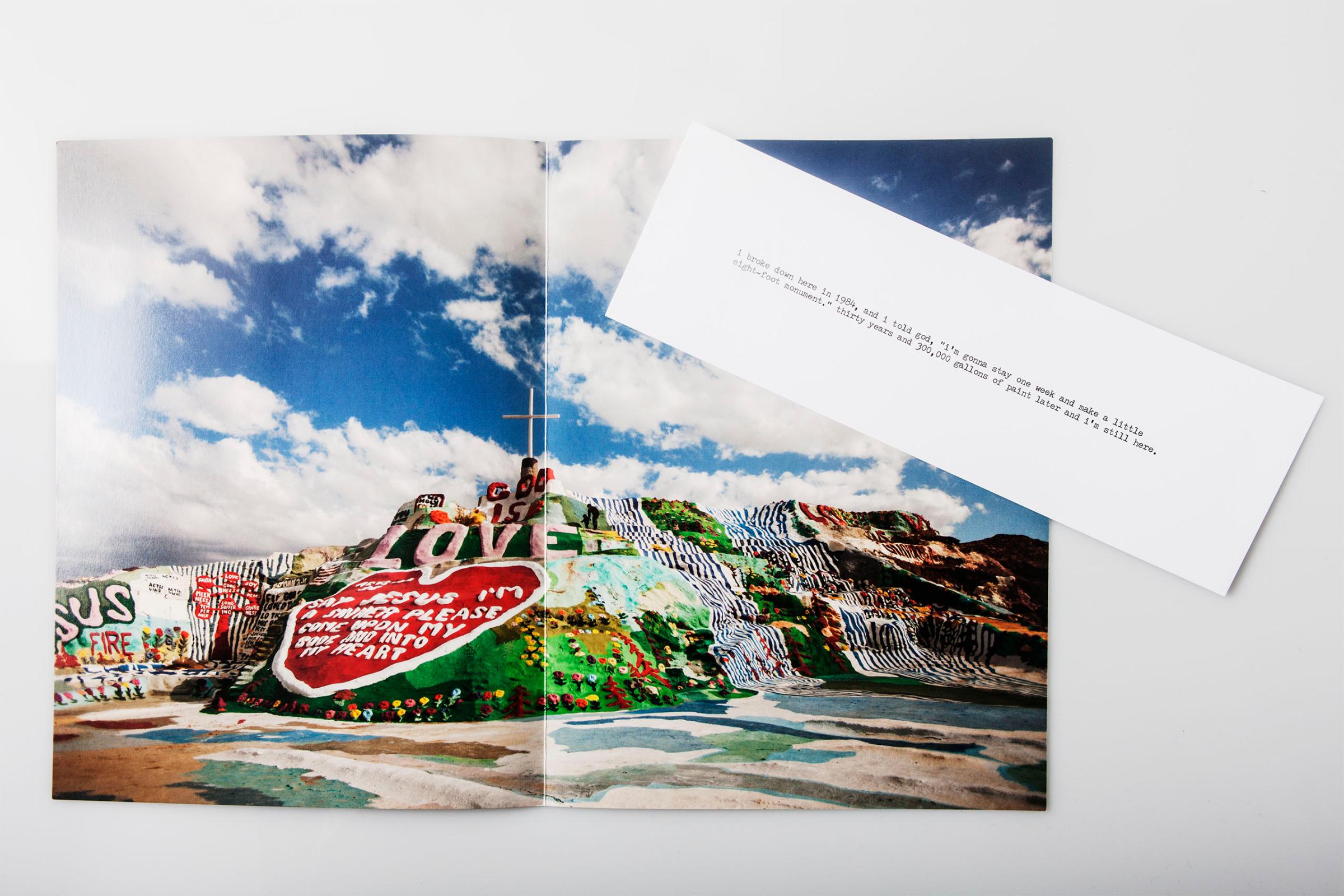

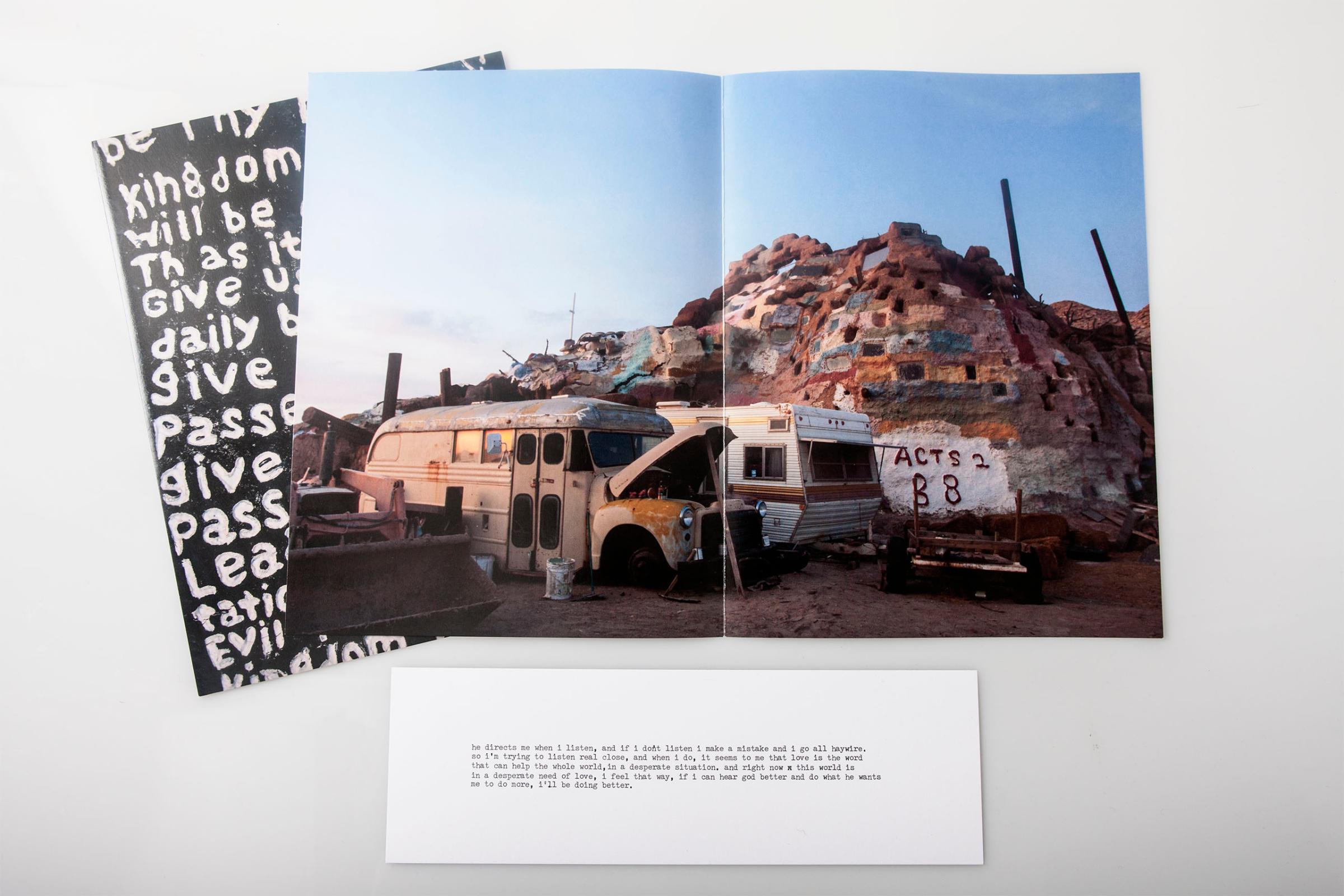

National Geographic photographer Aaron Huey’s latest photobook, Where the Heaven Flowers Grow, is a strange publication. From the outside, it looks like your usual book, but once open, it comes apart in a multitude of unbound photographs, notes, booklets, letters and drugstore prints. The result can seem overwhelming – Where do you start? – but, says Huey, readers should disregard conventions and just “feel free to take the whole damn thing apart and never put it back together the same way,” he tells TIME.

In the first installment of TIME LightBox’s Anatomy of a Photobook series, Huey explains how the unusual photobook came together.

Olivier Laurent: What drove you to that story in the first place?

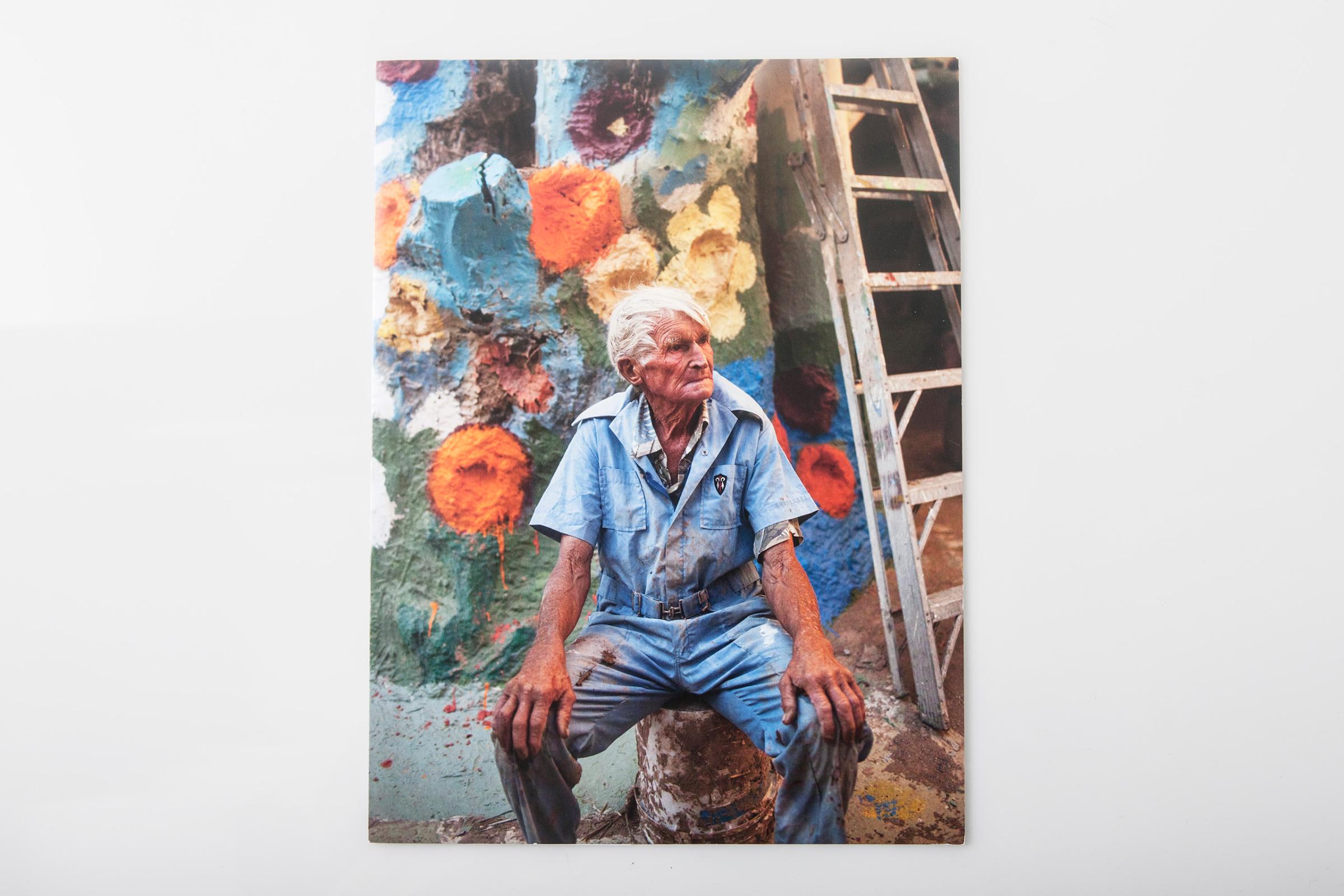

Aaron Huey: Like many of my previous projects, this is one I stumbled into, fell in love with, then stayed for. I found Salvation Mountain and its creator Leonard Knight when I was passing through to take a look at Slab City in 2007. When I met Leonard he could still carry a 50-pound buckets of adobe up a 30-foot ladder, but he could no longer carry an 80-pound hay bale up that same ladder. He was 77 years old, he was stuck, and he needed help finishing his mountain, so I helped him to carry the bales that day. The way his face lit up when he could see the mountain growing hooked me. Add to that the pure raw genius I saw in his art and mission and I knew that this would be a long term project for me. I’d never met an artist like this. Hell I’d never met a man like this.

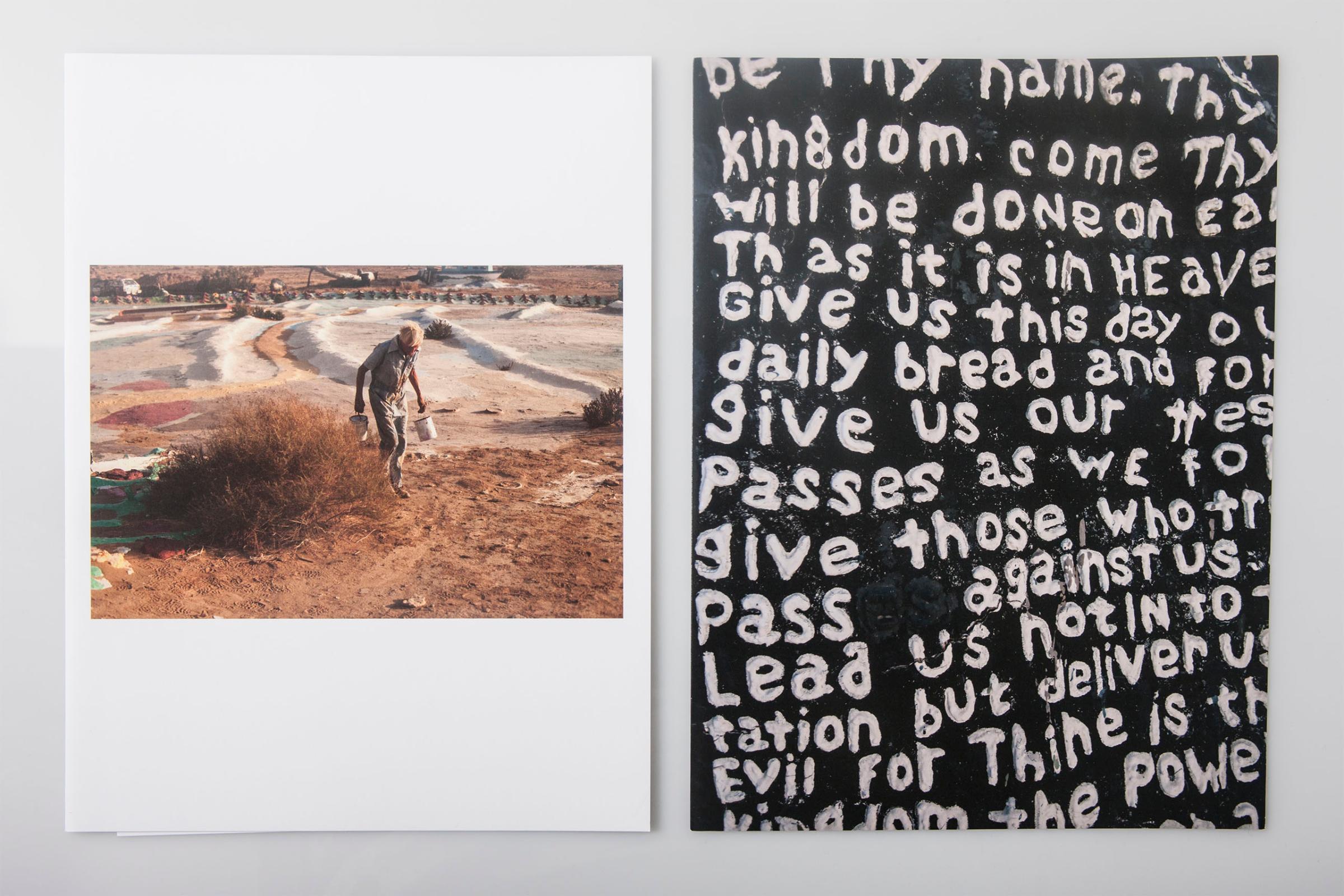

This was a man who lived in a small cabin perched on the back of an old fire truck for 25 years; a thin set of plywood walls was his only shelter from 115-degree summer heat. This was a man who had no belongings, no income, and no relatives within 2,000 miles. This was a man who spent every hour of every day prostrating himself to one goal: building a mountain that said God Is Love on it. Every day he did the same things: eat, sleep, work on the mountain, and give tours to every human being that stopped to see it. And Leonard had no ego about his creation because he didn’t consider himself “an artist.” We see people all the time building their version of a “mountain” in their lives as artists, but usually those people are so deeply soaked in ego, in an awareness of their fame, and obsessed with what elite club or agency they are in. And they play to that. Leonard didn’t do any of that crap. He just made his mountain.

I knew I’d be coming back again after that first trip, but I didn’t know for how long or what form this would take for several years. Like many photo projects that I do, this one just grew organically until it reached its logical conclusion.

Olivier Laurent: When it came to putting the book together, did you know it would be such a unusual object?

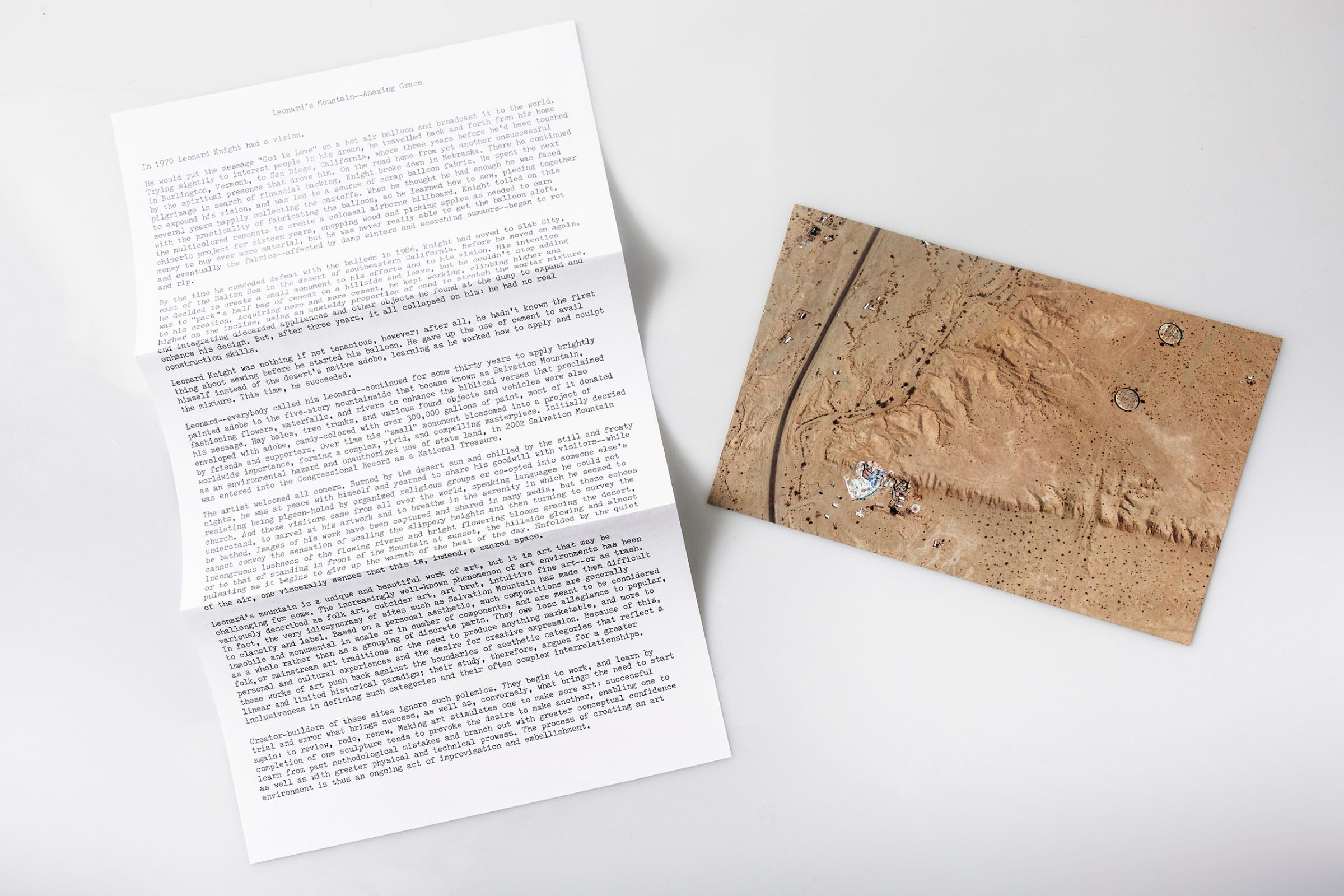

Aaron Huey: We knew it wouldn’t be bound, and it got both looser and more expensive to create every week, with every new “must have” object that I included. I think it was quite brutal for my business partner, Alisa Geiser, to watch. We had definitely seen other unbound books we liked – like Iris Garden by William Gedney – and we both agreed upon that initial and fundamental design choice. It was more of a museum in a box. I did know that I wanted to document as much of the actual surface that I could, and include that in the book, because after his death I knew that the elements would take some of it away, and that supporters attempting to preserve it would have to paint over Leonard’s work. To an average visitor this would not be noticeable, but I could tell immediately, when I returned soon after Leonard’s departure in 2011, which areas were painted by Leonard and which were done by caretakers. The surface of this place is very important, so the limited edition comes wrapped in a fabric print of a small piece of the mountain at scale.

Olivier Laurent: Why choose such a way of presenting this project?

Aaron Huey: Salvation Mountain is all texture and layers, and the more time I spent there the more I found, both in the mountain and in Leonard. I wanted to make this a bit of a dig for the viewer. Over the years that I visited this man and his art environment, I unearthed so many incredible objects and mysteries, like hundreds of hand-written song books that he had written in the 1970s and 80s. They were in an old truck opened up to the wind and rain and starting to mold and blow away. We pulled from that incredible find to create a single curated set that is included in the book. I also found a packet of 4×6 “dime store” photos taken in the 1980s of Leonard’s last attempts to inflate his giant balloon – Before the mountain he spent 12 years making a huge homemade balloon that said God Is Love. The balloon would not fly, and when it failed near the Salton Sea he made a small mountain with the same words on it that grew into the mountain that exists today. The postcards and letters and the rest of the found photos we included all contribute to this being more of a collection of artifacts than a book. If you read the introduction and the timeline you can see how each object fits into a specific period in Leonard’s life story, I hope people will spend the time with it to figure that out.

Olivier Laurent: What do you feel it brings to the audience?

Aaron Huey: I think some people will absolutely fall in love with this presentation and others will be terribly confused about how to navigate it. In a world full of quick reads and screen swipes this book will really make you slow down. I’d like to believe this way we are sharing Leonard’s life and art will make the reader feel like they are walking through Leonard’s museum; discovering new details about him, and being continually surprised with each new viewing. It is not a linear journey, you really need to get lost in it and continue to revisit and remix it.

We did edit the images to be able to work in a traditional page turning order, and for each coupling on the back of the spreads to work together, a double edit. But though the book can be laid out and thumbed through a page at a time “in order,” it is made to be completely taken apart. We really want readers to feel free to take the whole damn thing apart and never put it back together the same way. You can take out all the oral history cards, pin up the photos, mail the postcards, and sing from the song book. We don’t want the reader to feel like each card has to stay with each page and that each object has to stay tucked in a flap. I almost wish that the book would just spill out all over the floor when you open it so that you have to dig through it and reassemble it like a puzzle. I don’t think people are used to going through a book like that.

Olivier Laurent: How complicated was it to produce? How did you go about finding the publisher, and getting it packaged together in this way? How did you finance it?

Aaron Huey: Ridiculously complicated! Which is why I had to start a publishing company to make it! Every word is hand-typed on an old 1970s typewriter. I think five different printers made the various objects. We sweet-talked a consumer photo printer in Seattle into turning off the time-stamp on their machines so that the three “dime store” prints in each book maintained an historic feel. While we designed the book in-house, our main printer, the Fox company in Milwaukee, helped us figure out some of the complex logistics of manifesting those designs. Each book is hand assembled, which added greatly to the cost. When it came time to pay the bill, the book was financed by a generous loan from a private investor and patron of the arts, Jan Vermilye.

Olivier Laurent: Now that the book has been out for a few weeks now, what has been the feedback?

Aaron Huey: Feedback has been great from those who have visited the mountain or know Leonard’s world. I’ve been particularly moved by the responses we’ve gotten from Leonard’s family and friends. The stories they’ve shared about how this work has resonated with them, how it not only encapsulates the Leonard they knew and loved, but has revealed to them a Leonard they hadn’t known before, is deeply rewarding.

As for other audiences, to be honest I’m not sure how far this collection has reached into the fine art or photography community. It’s not photojournalism really, and I’m not sure its slick enough or spare enough to be cool for the high-art crowd. I hope more than anything that this work will begin to circulate in the community of curators and collectors and institutions that showcase great American art because I think Leonard’s work transcends the categories of Outsider and Folk Art. I believe that Leonard’s work needs to be seen, and it’s hard to do that without going to the mountain. Leonard didn’t really make portable art, so this is as close as many will get.

Olivier Laurent: Is this an approach you would look to replicate for future projects?

Aaron Huey: We want all our projects to be experimental and collaborative but we will likely ease up making our large scale trade editions so complex. We will make our most artifact-heavy books in much smaller runs in the future. This book was really a collaboration with Leonard over the years, and I want all our books to be collaborations between artists. We will be taking that a step further with a few upcoming books, bringing two artists together for each book, to create new imagery together, altering each other’s work so that the result brings something into the world that neither could have known before their meeting.

Aaron Huey’s Where the Heaven Flowers Grow – The Life and Art of Leonard Knight is published by Outsider Books.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com