This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

As Pope Francis visits the United States of America for the first time, the issue of climate change and whether a churchman has anything religious and relevant to say about it is in the forefront of attention. Francis has taken an unmistakable stand in favor of confronting the challenge of the man-made threat to our environment and our human habitat in his recent encyclical, Laudato Si’. Obviously there is something newsworthy today in addressing the world “On Care for Our Common Home,” as the title runs. In a historical context, though, when papal advocacy in regard to social issues is mentioned, the first thing that springs to my mind is not ecology, but economy: the rights of wage laborers. Running through both areas is the ethical issue of respecting the human dignity of persons in society.

A previous question of socioeconomic impact which, like Francis’ initiative, roused significant controversy, was papal promotion of a “corporative social order.” This took place with the promulgation of an encyclical during the Depression, Quadragesimo anno (QA) of Pope Pius XI in 1931. Here Pius XI delved into a serious economic quandary, the reshaping of labor-management relations. It turned out to be a flawed proposal for the 1930s, but it would experience a more prosperous adaptation in the favorable conditions of postwar Europe.

The scheme was called “corporatism” and was meant as an alternative to the two leading contenders in the European economic arena, socialism and capitalism, both seen as aggressively materialistic and exploitative. As opposed to socialist solutions, a corporatist social order would not aim at the government taking ownership and control of productive property, but leave (most of) it in the hands of stakeholders. As opposed to unmitigated capitalism, the stakeholders that counted in a corporatist economy would not consist exclusively of the owners and employers of firms operating in a laissez-faire market. Instead, the employers and employees of the main industries of a country would form collaborating organizations so that both would have a major say in regulating the competition and labor-management relations in their industry or sector.

In the circumstances of the 1930s, the pope’s vision lent itself to confusion with Mussolini’s Fascist version of “corporatism.” “Corporatism” was, after all, a rather diffuse conception having to do with less contentious labor relations than were characteristic of the industrial economies of the times. In Italy, the Fascist regime adopted the term in its formal self-definition of 1926 as a “corporate state.” This state and the Vatican City State formally recognized each other and came to terms in the Lateran Pacts of 1929.

With the approval of the concordat between Italy and the Holy See thus established, Pius XI turned to the broader issues of social justice, so as to celebrate and update the pioneering 1891 social encyclical, Rerum novarum, on its fortieth anniversary in 1931. He had a few Jesuit specialists commissioned to work in strict secrecy on a draft for a solid encyclical. When it was issued, the heading declared its topic to be nothing less than the “Reconstruction of the Social Order.” A key part of the document outlined an economic order regulated, to the extent possible, by industry- or profession-wide standards. To arrive at these agreed standards, collective bargaining between “syndicates” of employers and employees at different levels was presupposed. The role of the government would be limited to a possible recognition of the corporative economic body thus constituted.

Then (in paragraphs 91-95 added to the draft submitted by the Jesuit expert, Oswald von Nell-Breuning), Pius XI observed: “Recently, as all know, there has been inaugurated a special system of syndicates and corporations of the various callings which in view of the theme of this Encyclical it would seem necessary to describe here briefly and comment upon appropriately.” He went on to praise the Italian system (without identifying the country explicitly) on several counts, while adding a critical observation: “We are compelled to say that . . . some fear that the State, instead of confining itself as it ought to the furnishing of necessary and adequate assistance, is substituting itself for free activity; that the new syndical and corporative order savors too much of an involved and political system of administration; and that . . . it rather serves particular political ends than leads to the reconstruction and promotion of a better social order.” Thereby he went on record as saying that the Fascist corporative state was not what he was proposing. It violated the principle of subsidiarity (QA no. 79), a central value insisted upon in the encyclical.

Fascist organizations and newspapers in Italy had been decrying the persistence of political (Christian democratic) propaganda in Italian Catholic Action organizations all along. (The pope had agreed to ban all political activity from Catholic Action organizations.) Now Mussolini responded with an official crackdown on the Catholic youth organizations so dear to the pope. Police investigated and shuttered youth groups throughout Italy. Not until the end of September were they permitted to resume “purely spiritual” activities, after things were patched up between church and state.

The pope’s authoritarian bent was particularly evident in his readiness to make peace with Mussolini in the immediate aftermath of the reaction of the fascisti. Pius even compromised the principle of subsidiarity [Pollard 2014, 246-47] when it came to the Catholic authoritarian “QA state” in Austria from 1934 to 1938. Other authoritarian states like Portugal and Spain enjoyed similar approval.

World War II and the defeat of the Axis powers, together with the Cold War and the Marshall Plan, brought Pius XII, Pius XI’s successor in 1939, to a first distinct disavowal of the historical link between Catholicism and political authoritarianism. Corporatism made a comeback in a new democratic form. A striking case is that of West Germany. There, with the help of some “Ordoliberals” like Ludwig Erhard, the Christian Democratic Party and the Social Democratic Party converged around a highly successful social market economy. More broadly, subsidiarity and a kind of “societal corporatism” became integrated into Western European social and political thought at large.

Pope Francis has engaged the Church in the environmental marathon. Will its course be less fraught than that of the European social-market economy?

Paul Misner is professor emeritus at Marquette University of America and author of Catholic Labor Movements in Europe: Social Thought and Action 1914-1965 (Catholic University of America Press, 2015).

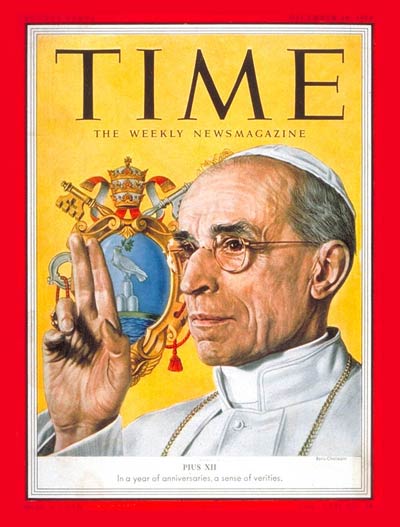

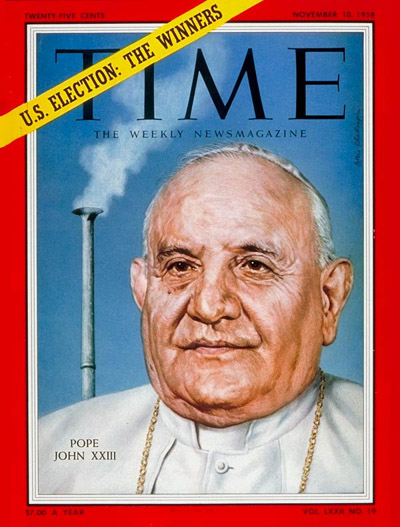

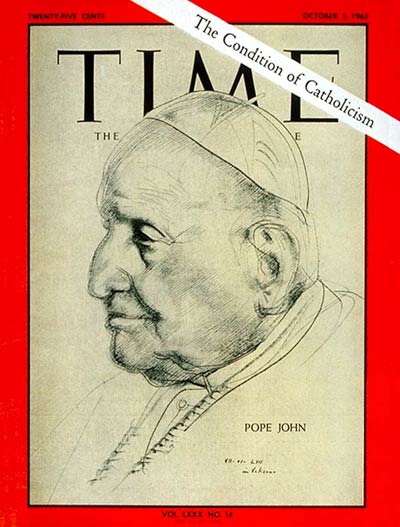

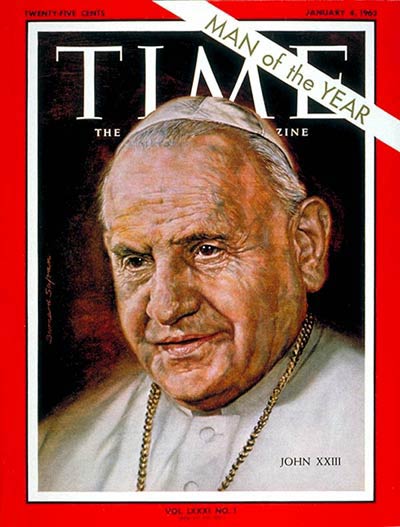

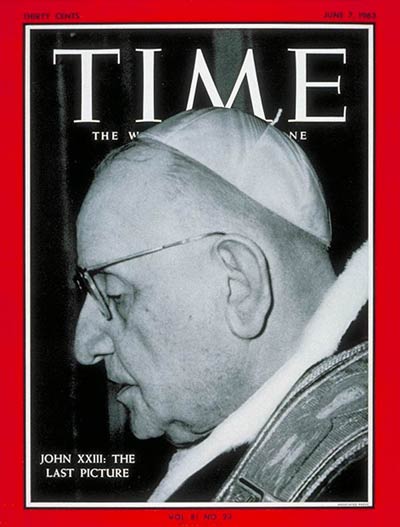

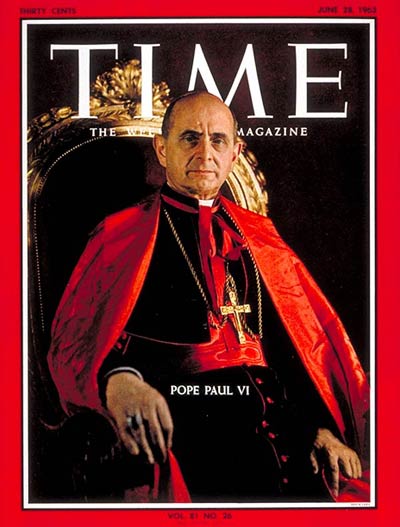

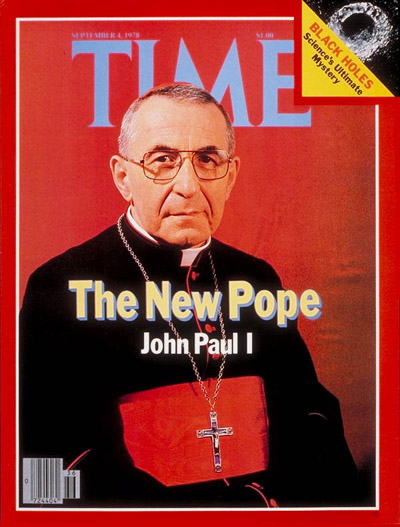

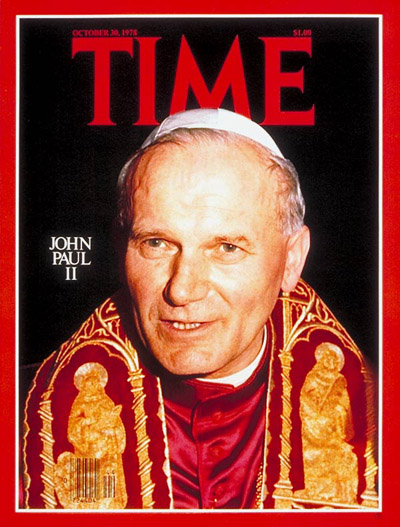

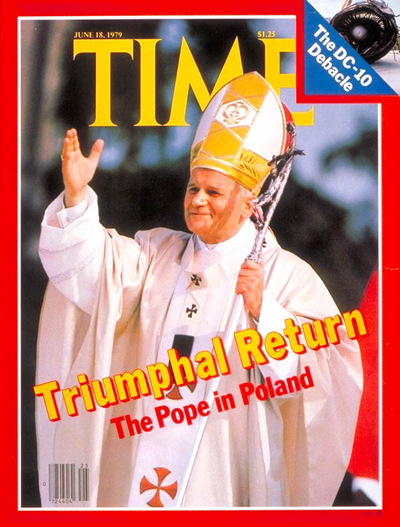

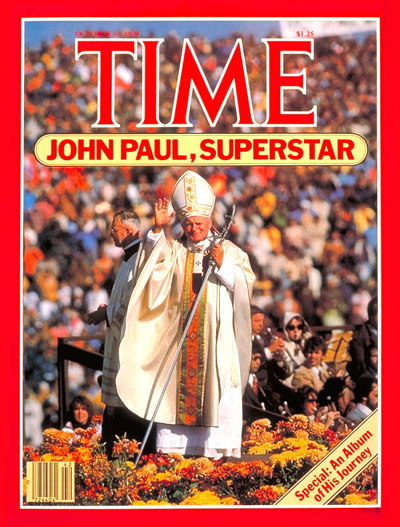

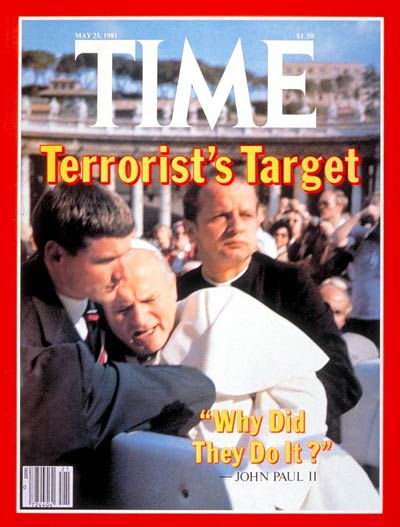

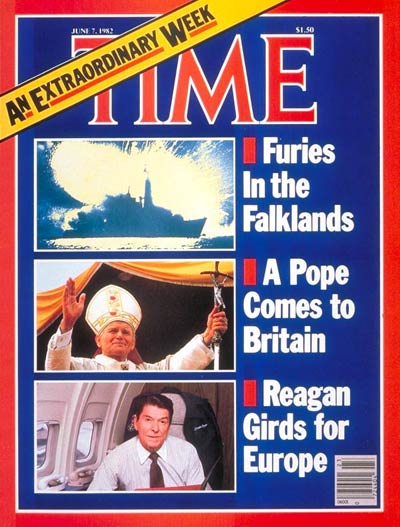

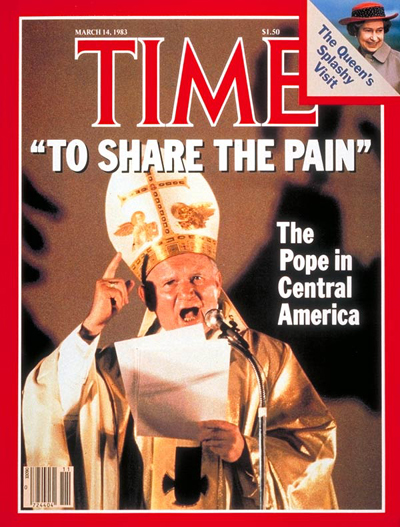

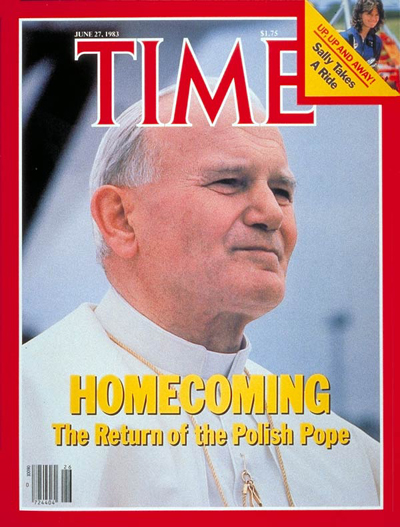

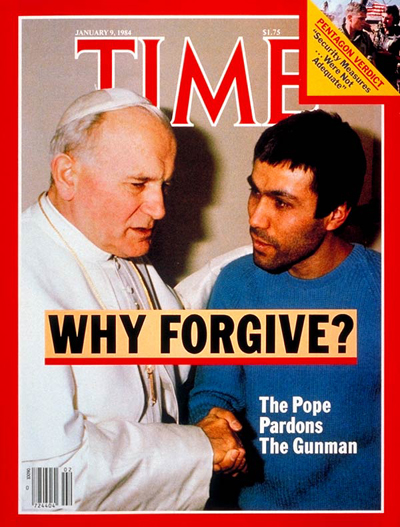

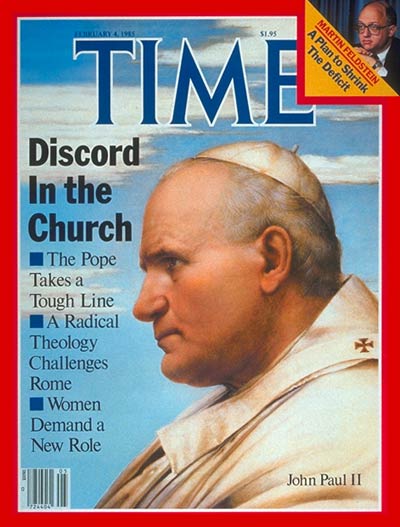

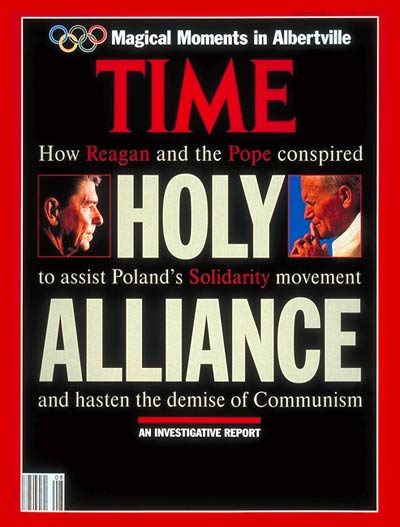

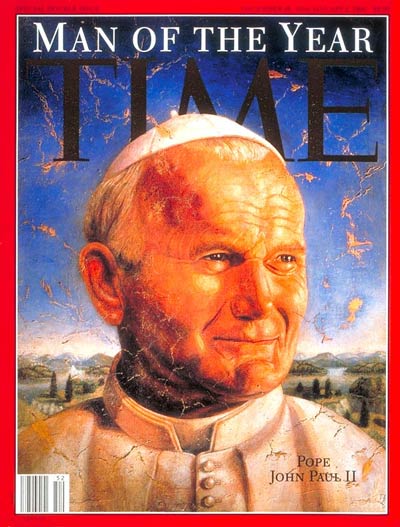

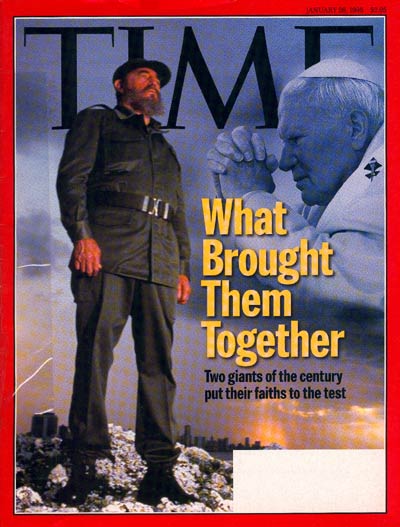

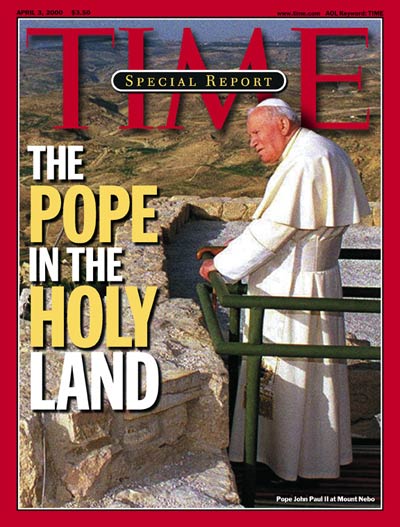

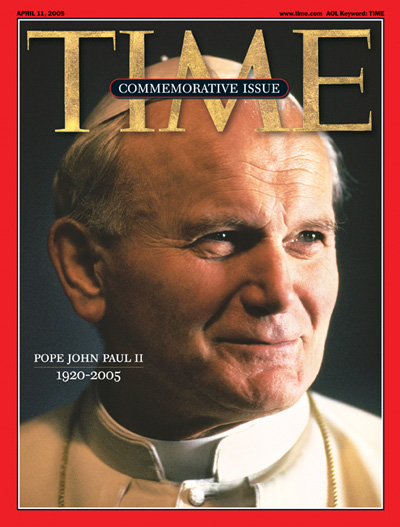

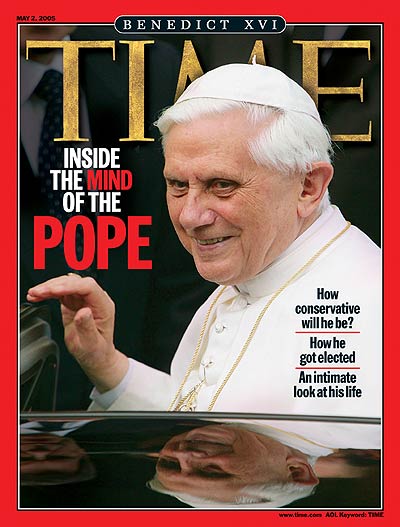

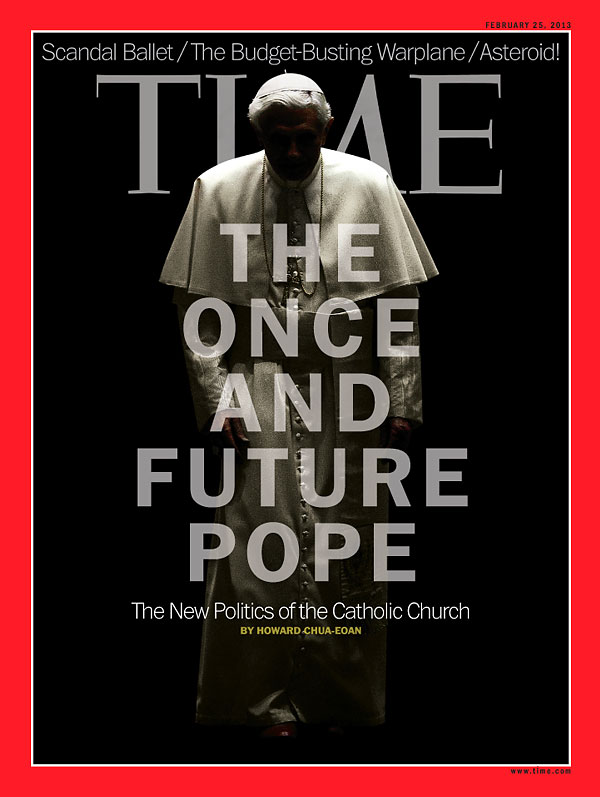

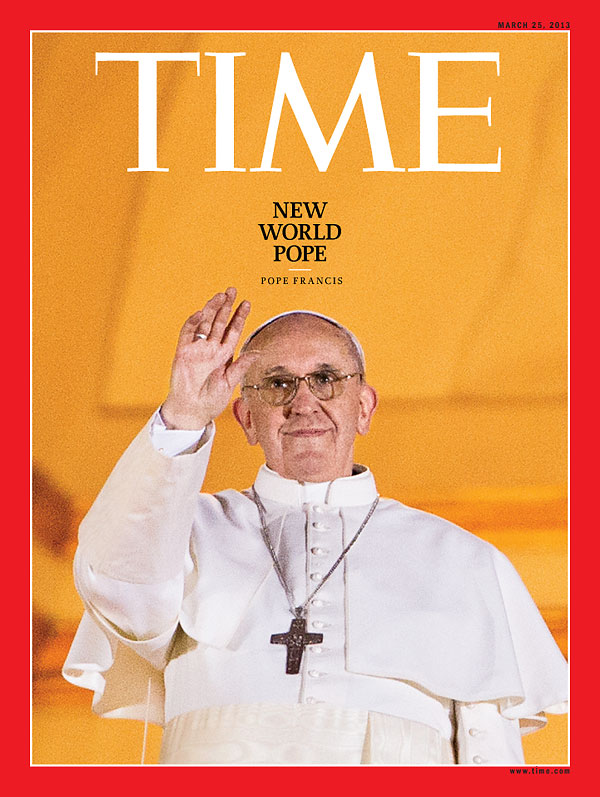

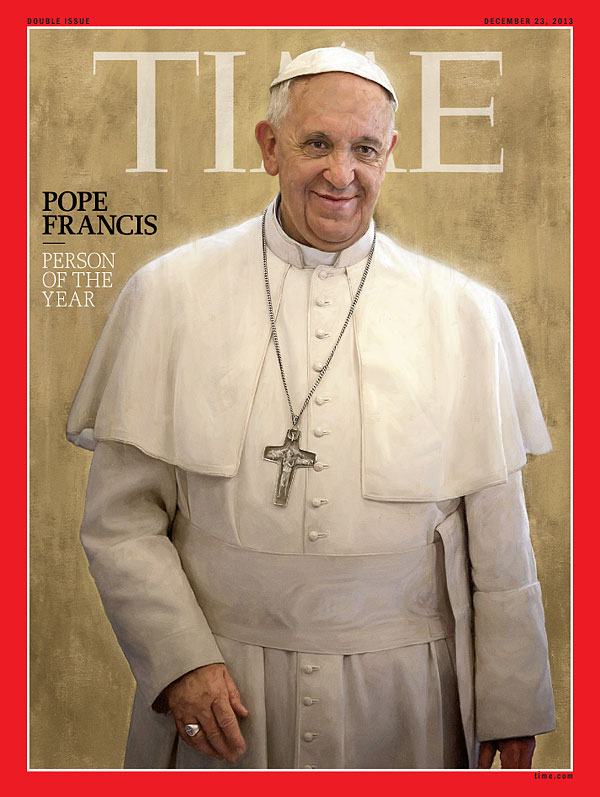

See Every Pope Who’s Ever Been on the Cover of TIME

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com