The Syrian refugee crisis unfortunately is simply the latest mass migration to challenge the global community. Just last summer, for example, the U.S. was the destination for tens of thousands of women and children fleeing rampant gang violence in Central America. Many other contemporary examples of large movements of people—Haiti, Africa and Vietnam—come to mind.

How do we as global community respond to large-scale migration flows caused by civil war, mass disaster or severe economic deprivation? Unfortunately, the law performs the worst in the situation where it is needed the most. Tight controls over numbers of people admitted do not help address mass migrations of people. More liberal admissions are urgently needed.

International law and the law of individual nations should be more open and admit migrants who want to work in low- and medium-skilled (as well as high-skilled) jobs that are highly valued by the economies of Western nations, which have experienced dwindling labor forces with decreasing fertility rates. We should show our true commitment to the global community by welcoming refugees fleeing violence, natural disaster, and lack of opportunity with open arms, not try to stop them from entering the country. A spirit of generosity, not stinginess, should guide our decisions with respect to the admission of migrants. Borders should be checkpoints not roadblocks to migrants.

Nations often fear “floods” of migrants crossing national borders. Carefully managed migration with numerical limits is most comfortable to the general public. Nations desire the perception of control over their borders and eagerly embrace legal and physical barriers intended to keep people out.

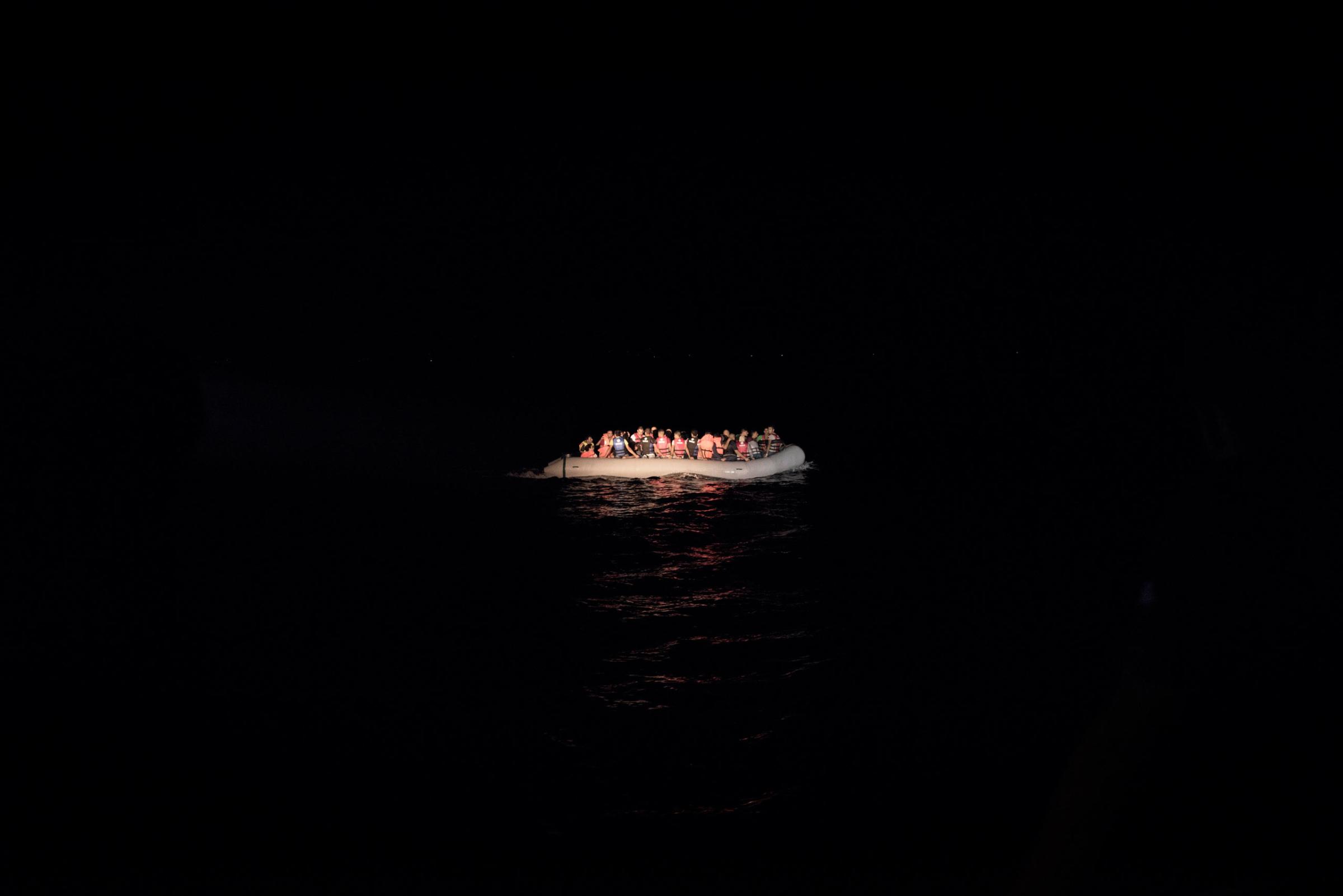

The problem with many, if not most immigration laws, is that rigid legal controls, numerical limits, and ceilings that are unrealistic, simply do not work. Whatever the legal and other obstacles, tens of thousands of desperate Syrians are willing to risk life and limb—and those of their children—to leave their homeland in search of safe haven. Central Americans fleeing violence have done the same since the 1970s. Moreover, people suffering from stifling poverty—think North Africans hazarding the Mediterranean Sea in hopes of reaching reach Europe, and Mexicans crossing deserts en route to the U.S.—also risk their lives to migrate to greater economic opportunity.

Why does international law fail many bona fide refugees? To establish eligibility as a “refugee” and safe haven in a country, the United Nations Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees requires an individual showing of the likelihood of persecution based on one of five grounds—race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion. The requirement of a specific individual showing is designed to ensure that nations are not overwhelmed by large numbers of refugees. But individualized showings can be close to impossible in instances in which large numbers of people leave their homelands en masse because of fear of widespread violence, natural disaster, and economic hardship.

Along those lines, the immigration laws of many nations require case-by-case decisions. Under American law, family and employment visas—with annual limits on overall visas and those issued per country—are generally limited in number. To obtain a visa, a prospective immigrant is presumed inadmissible unless he or she can prove otherwise. Because of restrictions on migration are unrealistic in many respects, the U.S. has an undocumented population of 11 million to 12 million people—migrants who found it necessary to find an alternative to lawful admission in the country.

Even after the hostilities in Syria calm, the world inevitably will see future cycles of mass migration from economic, political, social or environmental upheaval. We as a global community must reform the law to remedy its inability to respond to sporadic large migration flows in an orderly, flexible and humanitarian fashion. More liberal admissions standards that can respond quickly and flexibly to accommodate larger flows of people while ensuring public safety can be compatible.

To this end, current U.S. law could be changed to create a presumption of the admission of immigrants, rather than the presumption of exclusion that currently exists. This does not mean that the nation will have “open borders”; it instead will allow immigration officers to focus efforts on screening out true risks to public safety from our shores, not hardworking people in search of a better life.

More liberal admissions would allow more effective management of migration in situations like the Syrian refugee crisis. But beyond the practical effects, more liberal admissions of refugees fleeing violence is more consistent with the humanitarian aspirations of international refugee law. While some nations have stepped up to the plate to assist in the resettlement of refugees, others, such as Hungary, have literally barricaded the borders.

Recall that, in a regrettable chapter of history, the U.S. government turned its back on Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany on the S.S. St. Louis in 1939. Unfortunately, law has not fully changed to avoid such a tragic incident in the future. The time is right to reform the law to move away from an era of artificial limits to a time of humanitarianism, decency, and respect.

Witness the Resilience of Thousands of Refugees on Their Way to Europe

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com