CAIRO—Dozens of bodies in white shrouds lay on the pavement. Around them were piled blankets, flip-flops, even a wheelchair crushed in the mass of people. Ambulances wailed passed the crowds of pilgrims, dressed in the same white as the shrouds.

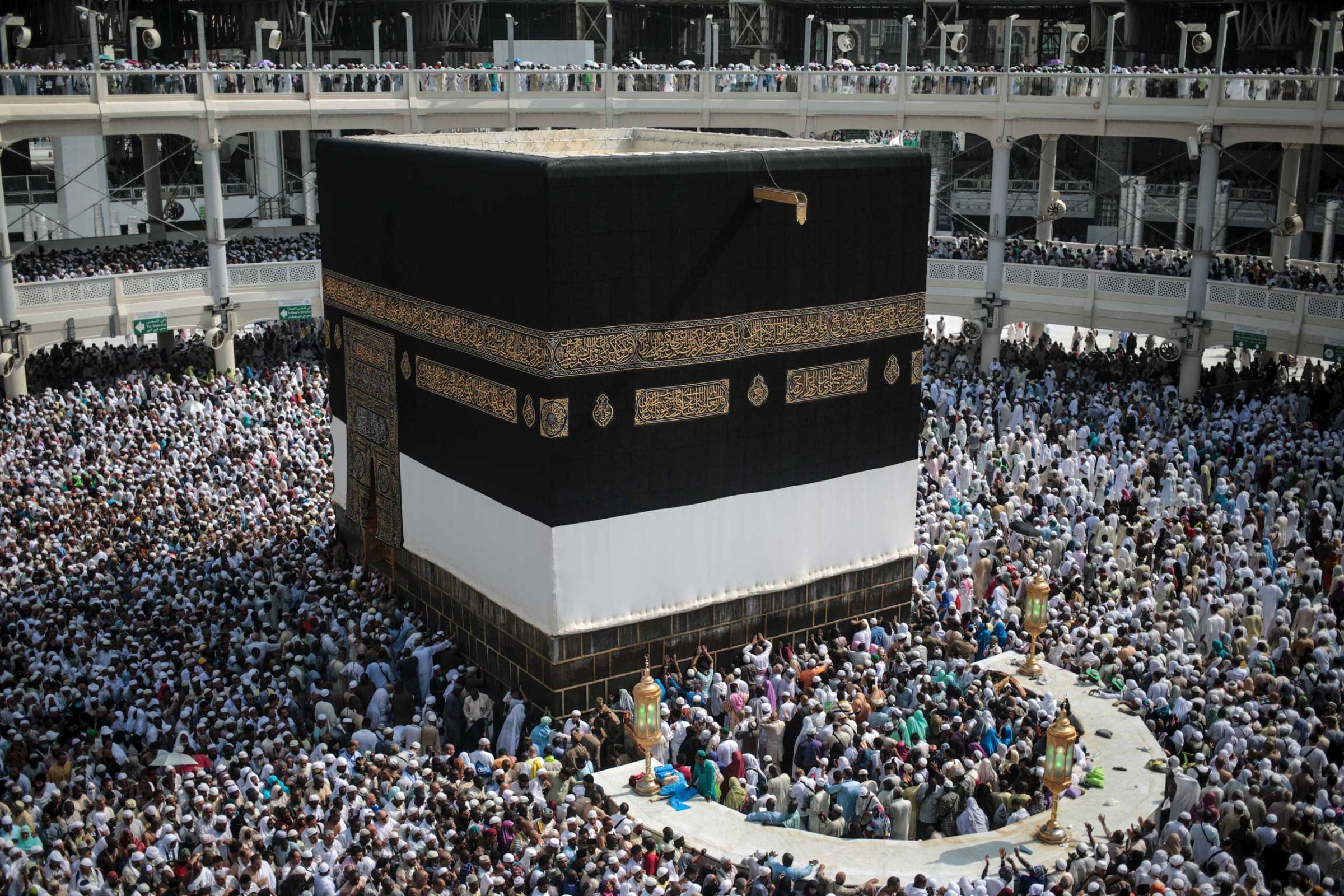

That was the aftermath of a stampede that left at least 717 people dead on Thursday near the city of Mecca, Saudi Arabia, during the hajj, an annual Muslim pilgrimage that drew more than two million people this year. Those scenes scenes emerged on videos that surfaced online after the disaster.

The stampede took place around 9 a.m. local time on Thursday during one of the rituals associated with the hajj, the symbolic Stoning of the Devil, in Mina, roughly six miles east of Mecca. Thursday was Eid Al-Adha, one of the most important holidays in the Muslim calendar, one that honors the willingness of Ibrahim to sacrifice his son on God’s command.

The deadly crush of bodies was the latest in a series of lethal incidents that have occurred during and around the hajj. Earlier in September at least 111 people were killed when a large crane collapsed onto the Grand Mosque in Mecca. In 2006, at least 346 people died in a stampede in the same area. But Thursday’s accident is the deadliest in decades.

As the custodians of the holy mosques of Mecca and Medina, Saudi Arabia has long taken responsibility for overseeing the hajj—and those repeated tragedies have raised questions about the Saudi state’s ability to manage this vast annual influx of people. As more and more Muslims around the world have been able to afford to make the trip, the number of pilgrims has swelled to more than two million, including more than a million who visit from abroad.

But the sheer numbers alone do not explain the repeated catastrophes at the hajj. Experts say that Saudi-directed development in and around Mecca—including massive hotels, malls, and luxury housing—have done little to ease the problems of crowding during the hajj, while the authorities have ignored safety concerns raised by urban planners.

See the Aftermath of the Hajj Stampede That Killed More Than 700 People

“The scale of this and the frequency of these sorts of things stand at odds with the amount of money that the Saudis pump into managing and ordering the hajj,” says Toby Craig Jones, a historian at Rutgers University who studies Saudi Arabia. “This is a highly sophisticated, regimented system”—and a rich one, given Saudi Arabia’s status as one of the world’s biggest oil producers.

“They have not sought to make the space usable by large numbers of people,” says Jones. “They’ve crammed it with hotels and real estate development. They’ve made it very difficult to have the hajj be a safe experience for people.”

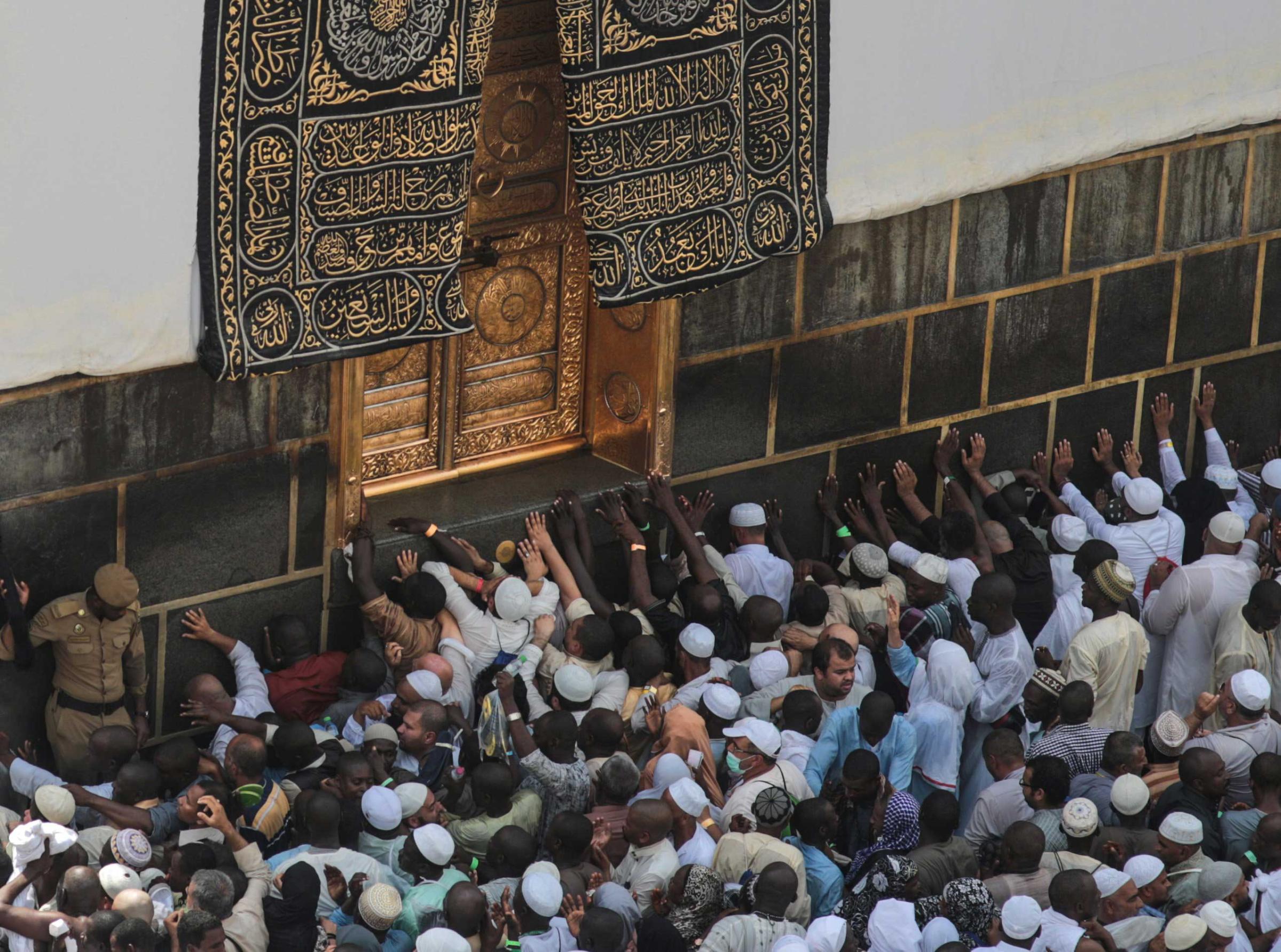

According to some accounts, Thursday’s stampede began when a huge crowd of pilgrims was heading in the direction of a tent where the symbolic stoning of the devil takes place. Another group started heading the other way, according to a BBC reporter on the scene. The two throngs collided, sending people scrambling over one another.

In videos taken by individual pilgrims, a grizzly picture emerged of the moments following the stampede. In one clip posted online, unconscious bodies are piled on one other. Others appear to be still alive, their limbs moving in the mass of people. (In a statement, the Saudi health minister, Khalid al-Falih, said the stampede may have been “caused by the movement of some pilgrims who didn’t follow the guidelines and instructions issued by the responsible authorities.”)

The disaster was the worst to strike the hajj since 1990 when more than 1,400 people died in another stampede inside a tunnel near Mecca, also on Eid Al-Adha.

The deaths also pose a new challenge for Saudi Arabia’s King Salman, who ascended to the throne in January. The new monarch has adopted an aggressive posture in regional affairs, leading a coalition of states in a military operation against Shia Houthi rebels in neighboring Yemen, and

Analysts also say that Saudi Arabia’s autocratic system of government is partly to blame for the repeated deadly incidents during the hajj. In the past, senior government officials have rarely been held accountable for such incidents.

Saudi authorities have historically viewed the hajj has a political and security challenge, viewing with suspicion the huge numbers of pilgrims who visit from places like Iran, the kingdom’s geopolitical rival. (In the aftermath of the stampede, Iran complained that Saudis had not been treating the scores of dead Iranians, and that Iranian officials had not been allowed near the dead.) But that approach to managing the hajj can come at the expense of basic safety concerns.

“The underlying interest on the part of the Saudis is meant to manage an event in a way that minimizes political risk,” said Jones, the historian. “I think the Saudis see the hajj as a problem they have to manage, rather than as an experience that they need to facilitate.”

See Muslim Pilgrims Flocking to Mecca for the Hajj

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com