On Sept. 25, 2014, Thomas Duncan arrived at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas, Tex. with a high fever, dizziness and nausea. The fact that he had recently arrived from Liberia, where he had helped drive an Ebola-stricken woman to the hospital, was only disclosed and entered into his electronic health record later. The doctors who examined him sent him home with antibiotics.

Days later, Duncan returned, this time in an ambulance and much sicker. He was diagnosed with Ebola, and two weeks later, he passed away. More people became infected with Ebola either here in the U.S. or in West Africa and were cared for at U.S. hospitals last year: Nina Pham and Amber Vinson, two nurses who cared for Duncan; a cameraman who had been filming the Ebola epidemic in West Africa; a Doctors Without Borders physician; and two missionary health care workers, among others.

What did the U.S.’s top health leaders learn from the experience, and how prepared is our health system for another case of Ebola or another infectious disease? Here’s what they did then, what they wished they had known, and how Ebola changed the way the U.S. will respond to future outbreaks.

Sylvia Burwell, Secretary of Health and Human Services

As we think about the question of what worked and what didn’t, we have to remember that this was an unprecedented challenge in scope, scale and clinical complexity. It’s something that required the whole of government to respond, and I think we are more prepared to do that a year later.

MORE: The Ebola Fighters

First, our clinical approach to treating Ebola in a typical intensive U.S. hospital setting posed different challenges. While we had years of experience through MSF (Doctors Without Borders) and others who had helped in West Africa, they were treating Ebola in a very different clinical setting. So applying what we learned about doing so in our clinical setting was a place where improvement was needed, and it was quickly made. We always want to focus on correcting errors of what worked and what didn’t, and we did that on an ongoing basis. We saw that when the CDC made immediate changes to the guidelines for personal protective equipment.

Second, we found out that we needed more specialized treatment centers for Ebola and other special pathogens for this type of intensive, complex clinical treatment.

I’m still concerned about Ebola because we still have cases in West Africa. And as a nation, we are concerned about the next thing. We can’t just fund efforts like Ebola treatment centers at times when there is a critical problem. We need to make sure we are continuing to do that on an ongoing basis.

MORE: WHO Politics Interfered With Ebola Response, Panel Says

Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

To me, there are three main lessons in the Ebola epidemic. First, every single country needs a strong system to find and stop threats. Second, when countries are overwhelmed, the world needs to be able to surge in rapidly. Third, infection control in hospitals has to get better.

Clearly, we wish that the hospital [in Dallas] had diagnosed Mr. Duncan the first time he went in with a temperature of 103 F and a history of having come from Liberia. Clearly, despite the efforts of the nurses to avoid infection, two nurses got infected. That was not acceptable. Therefore we rapidly intensified our recommendations for infection control with respect to Ebola.

We worked extensively with hospitals around the country and invested $340 million to enhance state and local health care systems preparedness. We designated facilities and funded more than 55 local and regional Ebola treatment centers.

One of the things we learned from this epidemic is how challenging it is to care for patients with Ebola safely. CDC staff had cared for patients with Ebola in Africa in the 70s, 80s and 90s, and we had never seen infections in our staff. But things were different this time around. For one, there was much more explosive diarrhea in patients than we had seen before. Second, the nursing care in the U.S. is much more intensive—with nurses [frequently] turning and caring for patients—than it is in the Ebola unit in Africa. Third, in retrospect, we should have known better. There are 75,000 deaths each year from infections spread in hospitals in the U.S.. We know no matter how good our recommendations for hand washing and personal protective equipment are, we have to have a large margin of safety for how they will actually be implemented in the field.

If we look back at the past year, there are things science learned that we didn’t know at the time, so there are things we could not have done differently. There are things that with 20-20 hindsight, if we had known everything that we know now, we could have perhaps been more effective. Then there are the things, even knowing what we knew then, we could have done differently. Once we knew the first nurse was infected, we should not have allowed Amber Vinson to fly, even though she didn’t have a fever. Because she had the same exposure and should have been considered high risk, we should not have allowed her to fly.

Now, in the U.S., we need to guard against complacency. There will always be new infections. We know we have to keep our public health system strong and prepared to respond to everyday threats so we can surge up when needed to deal with an emergency.

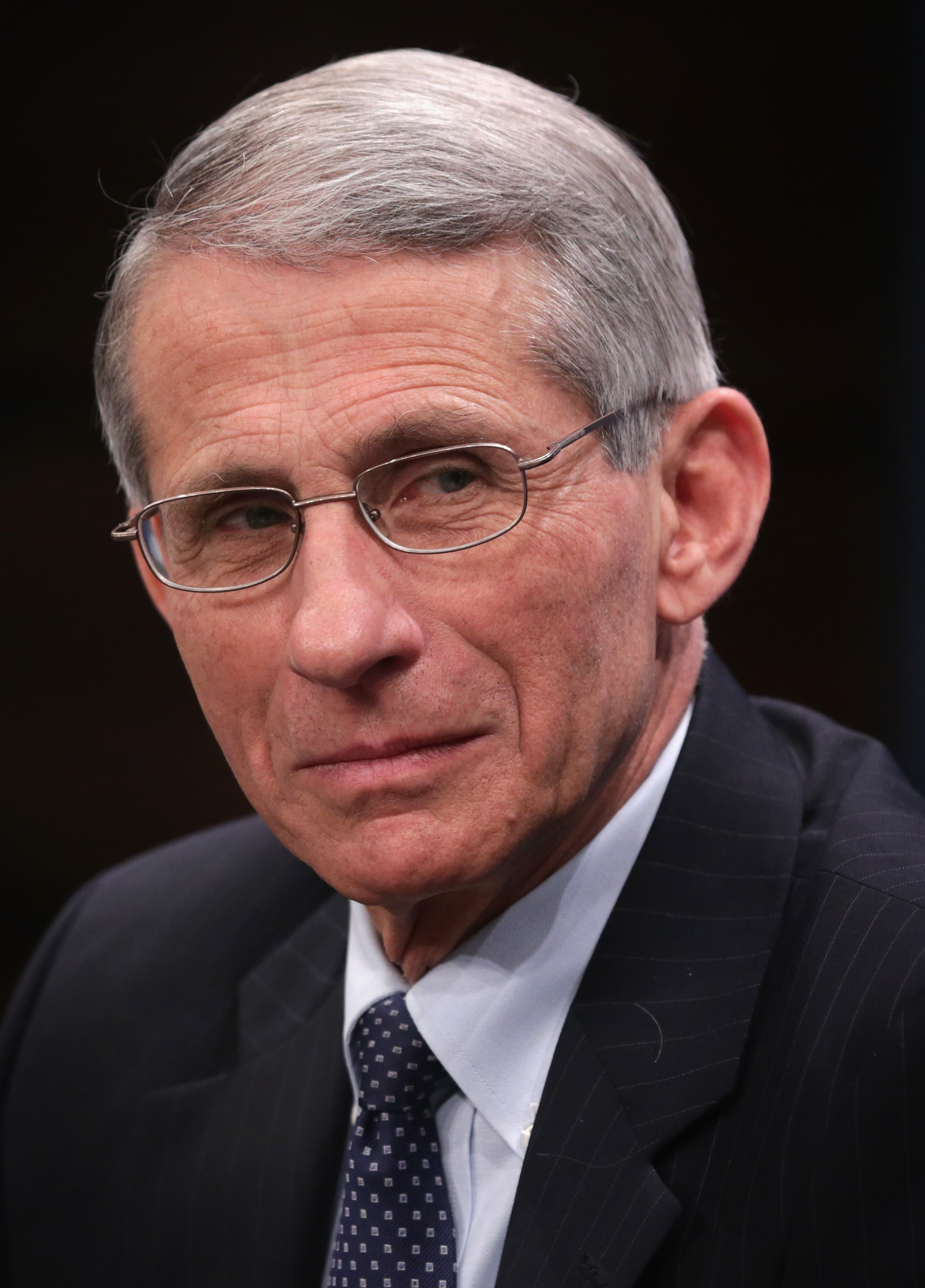

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases

The lesson I learned was more a medical lesson than anything else. I was under what now turns out to be the misimpression that if you can get every Ebola patient into an intensive care setting, keep their fluids and electrolytes properly balanced and not allow them to develop hypotension or shock—if you are just able to monitor them—that inevitably they will be fine. What I learned from taking care of the second patient at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is that there is a small subset of patients in whom the virus is so virulently attacking the body that everything starts to collapse, even if you give them optimum fluid replacement therapy. This happened to me and my colleagues as we took care of our second patient over a period of two and a half weeks in March.

The person [a healthcare worker who was infected while working in Sierra Leone and who remains anonymous] came in and was still conscious, but clearly very, very sick. We put in the appropriate IV access, the appropriate tubes and intensive care paraphernalia and kept his fluids perfectly in balance. He never went into shock. And even though he had massive diarrhea and vomiting, we meticulously kept up his fluids. We thought, Okay, we just need to do this for a while and he will be home free. Then, to our amazement, he went into respiratory failure, requiring emergency intubation. It was the virus attacking his lungs. Then he went into renal failure—how could that possibly be? Then he had cardiovascular abnormalities. Finally he developed severe inflammation of the brain.

There were two or three of us in the room at any given moment, all day and all night, and he survived. Otherwise he would have died five times over. What this tells us is that for a small subset of people, being treated in a very intensive care setting is necessary to save their lives.

The lesson is that the next time something like this occurs—especially if you’re dealing with a disease that can spread among healthcare workers—you really require training and proper equipment. We would have been in danger of getting infected if we weren’t very, very well practiced in how to put on and take off the personal protective equipment and how to give intensive care to someone who is desperately ill.

The lesson is that not everybody and not every hospital can take care of a desperately ill Ebola patient in an intensive care setting. There is a big difference between admitting somebody and isolating them when they are not that sick, versus really administering minute-by-minute life-saving therapy with all the proper machines, respirators and pick lines. You’re not going to do that in a general hospital. That was patently obvious to me as I went through the care of this patient day and night.

In a broad sense, we need more than just a few hospitals—in the case of Ebola, NIH, Emory, Nebraska and Bellevue—in case there is a large number of patients. Taking care of people in intensive care requires more than just superficial training. We trained and trained and trained for that, so when we had to do it, it came naturally. You don’t just pull up a website and ask how to do it.

I never felt that you could have many, many, many hospitals be able to do the kinds of things we did at NIH and that Nebraska, Emory and Bellevue did. I never felt comfortable with that.

I also found it really good when Ron Klain came in as Ebola response coordinator. He had a extraordinarily positive capability of coordinating a group of very powerful, independent-minded agencies. Without telling anybody what to do, he created a great forum for communication, cooperation, collaboration and synergy. So I think having someone like that is a really good idea.

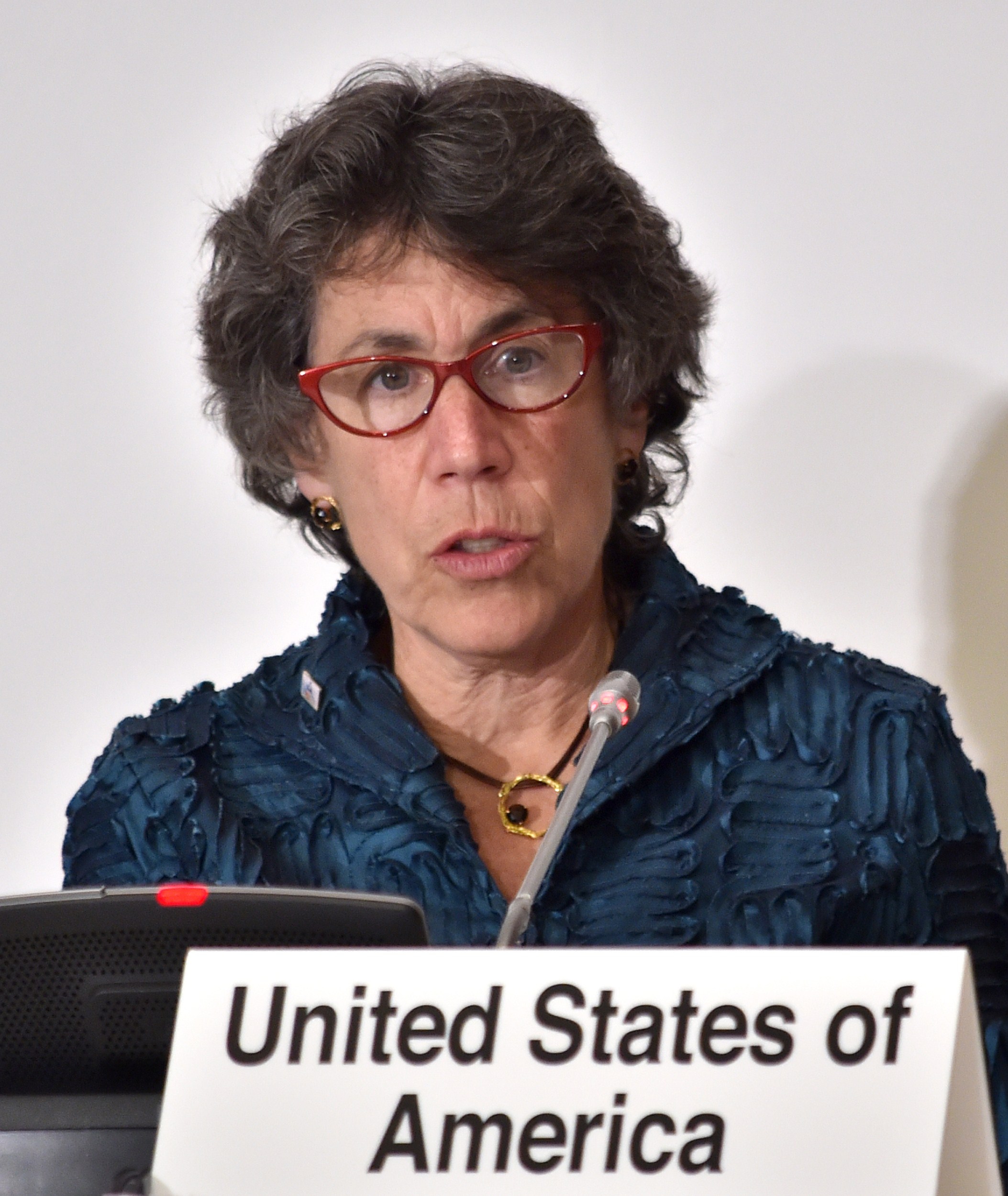

Nicole Lurie, assistant secretary for preparedness and response Health and Human Services

We learned a whole lot and are in a far, far better place now than we were a year ago. We learned that it’s complicated to take care of Ebola patients. It requires a hospital and staff with really great training in infection control practices and the ability to deliver really sophisticated care while maintaining isolation and infection control practices to the highest degree.

That’s why every state now has at least one hospital that can assess potential Ebola patients. We have 55 Ebola treatment centers across the country. And we have a regional system of nine regional centers that could treat Ebola, with more specialized capacities to treat other highly infectious diseases as well.

In some sense, we were really quite surprised to learn last year that many health professionals were never really taught how to put on and take off personal protective equipment in the safest way possible. Taking care of very sick Ebola patients requires very specialized care and specialized training. From that perspective, when you have designated centers for Ebola treatment, the more experience people have, the better and safer care they can provide. That was certainly a lesson learned, and it’s a really important one.

The other lesson, and the reason we created the designated centers, was that in the beginning, many hospitals didn’t want to take care of patients with Ebola. They were terrified, their staffs were terrified and the public and the community were terrified. They were very, very worried, frankly, that they would lose business. So many hospitals sought to avoid it.

So it was probably unrealistic [to expect every hospital to be able to care for Ebola patients]. There are certainly hospitals that can’t do it and other hospitals that don’t want to do it. The demands of taking care of an Ebola patient are so intensive that a number of hospitals could not carry on normal business functions. The lesson learned is that we need designated Ebola centers to do it.

But that requires funding. We now have funding in place to support the regional network of centers financially for the next five years. But our country has a big national attention deficit. When things recede in the rear-view mirror, we like to forget about them, forget that they need funding and forget the need to practice and exercise and train. We’re going to have to find ways to sustain the network far into the future. Because it’s not a matter of if—but when—the next really scary infectious disease comes.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com