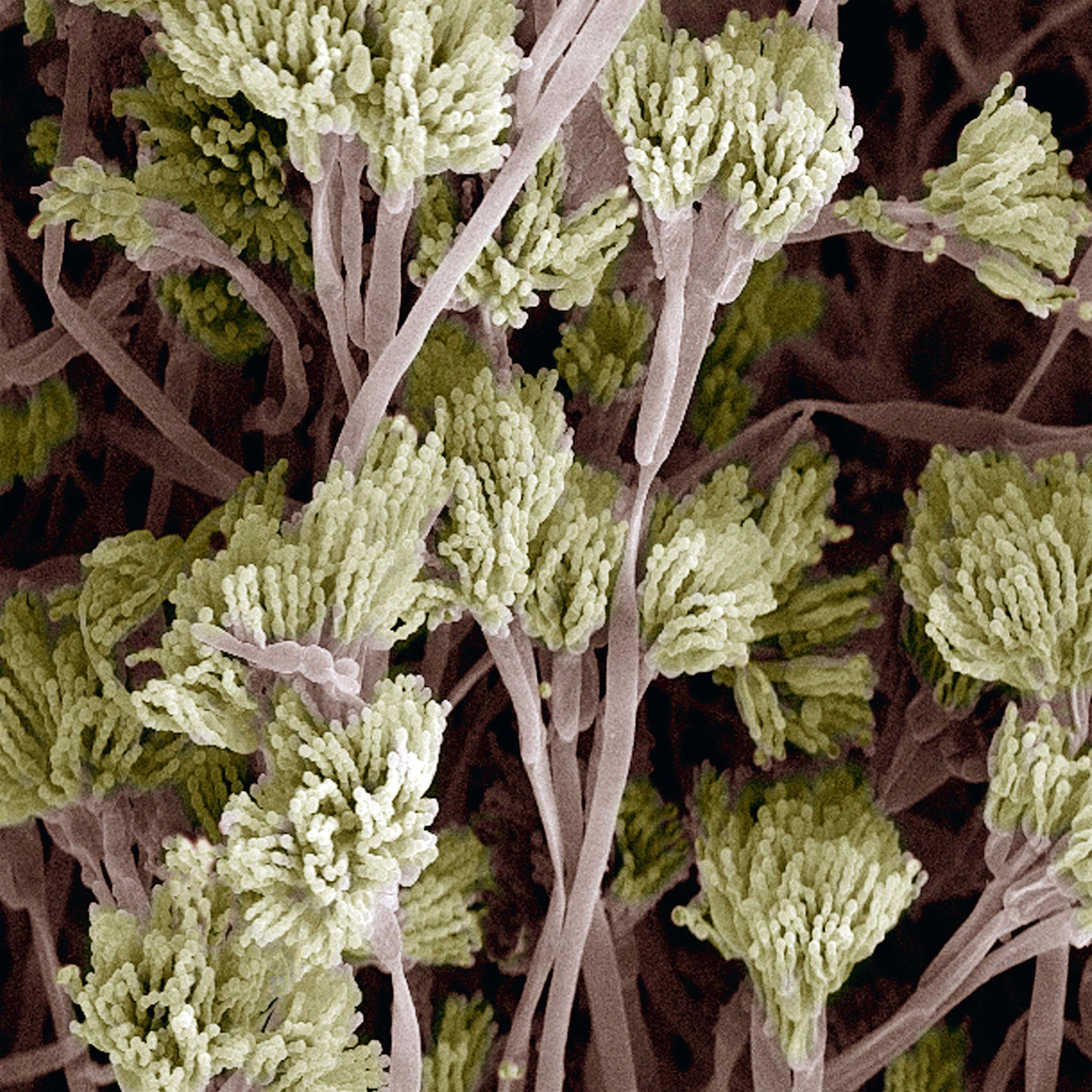

You did a lot more in the last 24 hours than you think. Yes, you got up, went to work, took care of the kids. But in your spare moments, you also found the time to shed at least 24 million biological particles—bacteria, viruses, spores and more—into the air around you, or a nifty 1 million nasties per hour.

If it’s any consolation, you’re not alone. We all continually emit our own microbial cloud into the air and onto nearby—and not so nearby—surfaces. Now, according to a new study in the open-access journal Peerj, scientists can distinguish the make-up of the cloud is uniquely yours—a personal marker that is as particular to you as your fingerprints or your genome. That’s a biological calling card that could have implications for epidemiology, environmental engineering or even, intriguingly, criminal forensics.

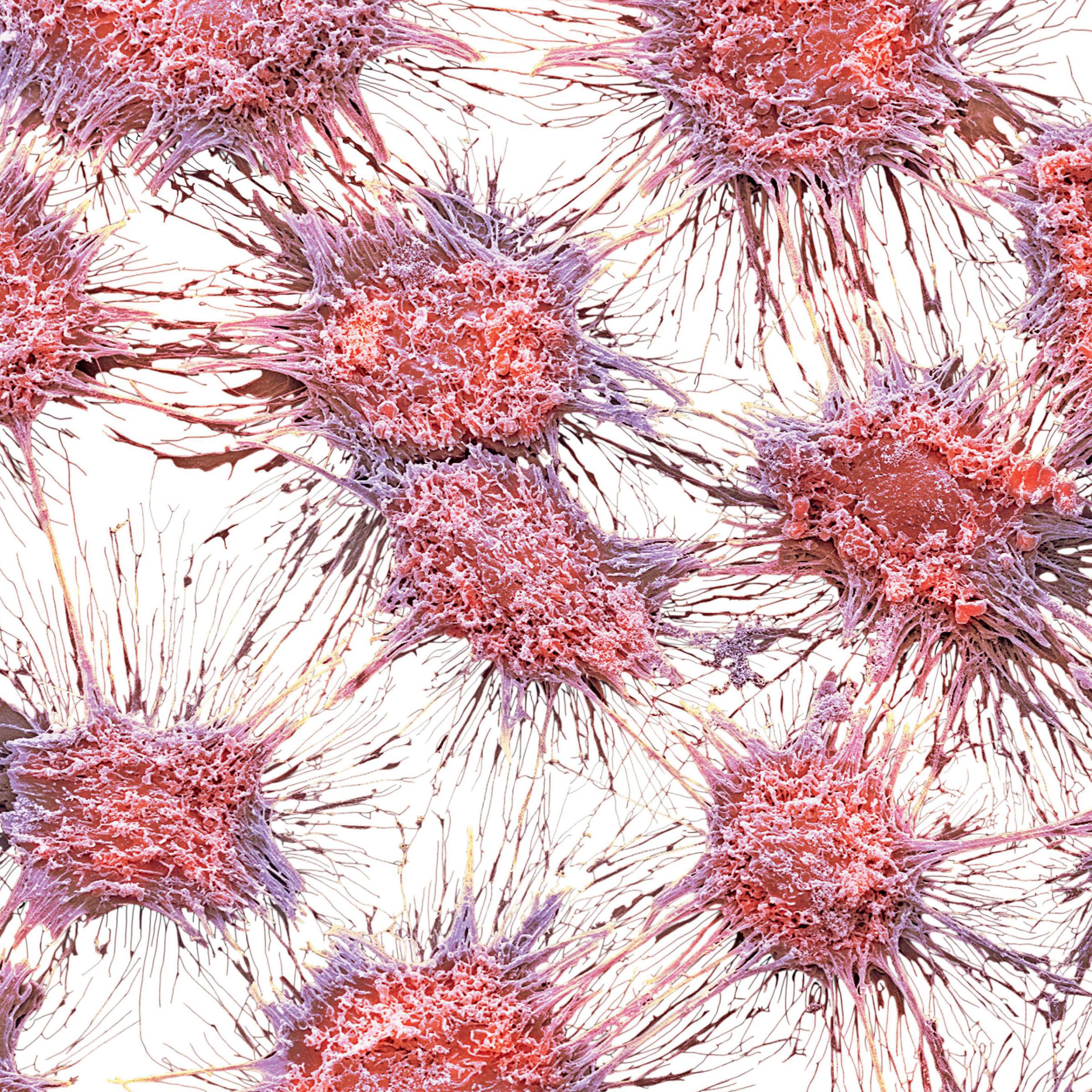

The new study was conducted by a group of investigators from the University of Oregon, led by environmental scientist James Meadow. The team already knew a lot about how readily human beings leave their microbial mark on their surroundings. Within just a few days of moving into a new home, for example, the occupants have already filled the air and seeded the surfaces with detectable microscopic organisms.

MORE: Can Specks Of Dust Help Solve Crimes?

And while microbes shed outdoors may be quickly dispersed with the wind, microbes shed indoors—in what environmental scientists call the built environment—stick around and collect. Since people in industrialized societies spend an estimated 90% of their day indoors, that’s a lot of time for us to steep in one another’s overlapping clouds.

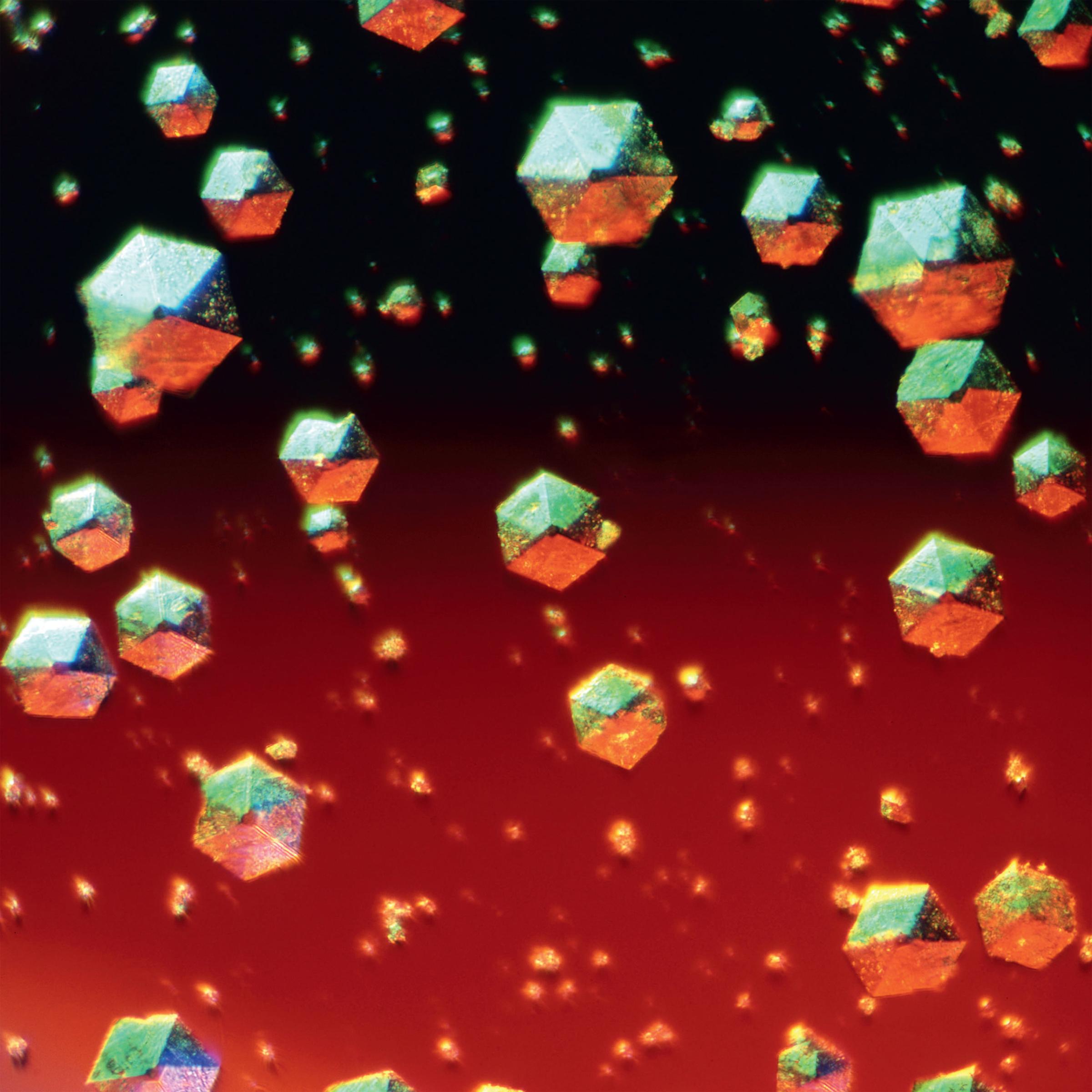

To determine how distinct those clouds are, the investigators ran two experiments. In the first, they had three subjects spend two hours one day and four hours the next sealed alone inside a sanitized sampling chamber. All of the surfaces within the chamber had been cleaned with antiseptics and the air had been filtered. If the chamber grew too hot or too cold, the temperature could be adjusted via heating coils in the floor—avoiding the contaminants that would be introduced by an air conditioner or a forced-air heater. At the end of the sessions, microbial samples were collected from several settling dishes placed near the subject.

In the second experiment, eight different subjects spent just 90 minutes at a time confined in the chamber. After that comparatively brief period, the air, not the surfaces, was sampled for microbes.

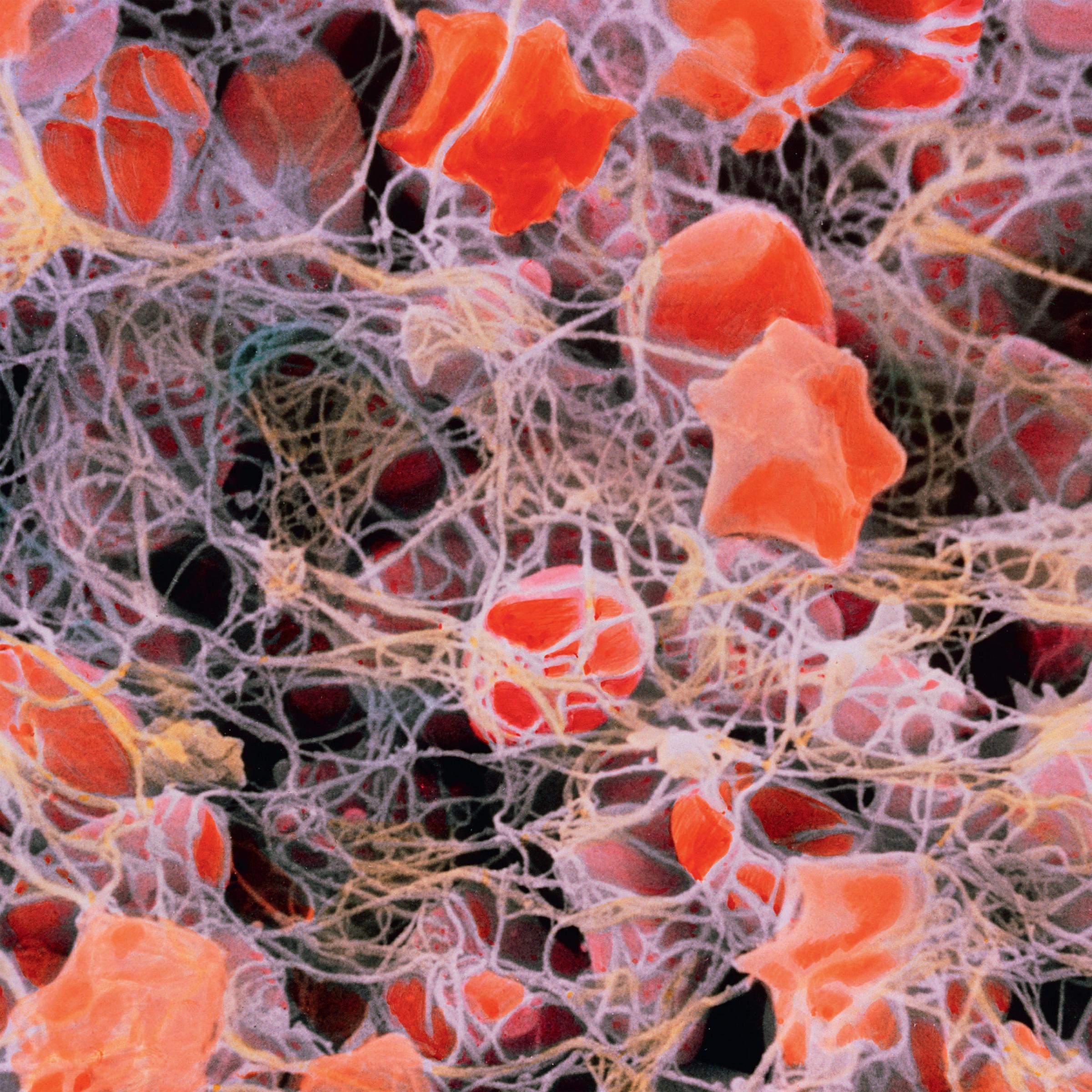

For simplicity’s sake, the researchers limited their analysis to 12 different bacterial families—including Staphylococcus, Streptococcus and Lactobacillus—which are common parts of a human microbiome and are usually found in higher levels in rooms people have occupied. Comparing the samples they collected from the chamber to samples they collected directly from each individual, they found that while all of the subjects emitted more or less the same collection of microbes, the ratios of each were indeed unique to the individuals.

“Our results confirm that an occupied space is microbially distinct from an unoccupied one,” the authors wrote, “and reveal for the first time that individuals occupying a space can emit their own distinct personal microbial cloud.”

The differences among the samples ranged from as little as 4% of the bacterial population to as much 61%. The presence of one bacteria family alone—Lactobacillus—was sufficient to determine the gender of the occupant, because it is a microbe most commonly found in vaginal samples from healthy women.

While all of the microorganisms studied are harmless in the right balance, the way they distribute and settle could provide new insights into how disease-causing pathogens make their way throughout a population. Crime-scene investigators too would surely love to use a lingering microbial cloud to, as the researchers wrote, “detect the past presence of a person in an indoor space.” A lot of work, however, would have to be done before the technique could be considered reliable—much less legally admissible. For starters, the authors themselves concede, the average crime scene has not been scrubbed, sanitized and air-filtered before the bad guy entered, providing a clean canvas onto which microbial evidence could be dropped.

Still, if the study proves anything it’s that all of us, as Walt Whitman would have it, contain multitudes. And more than we ever knew, we are forever letting a whole lot of our interior critters out to play.

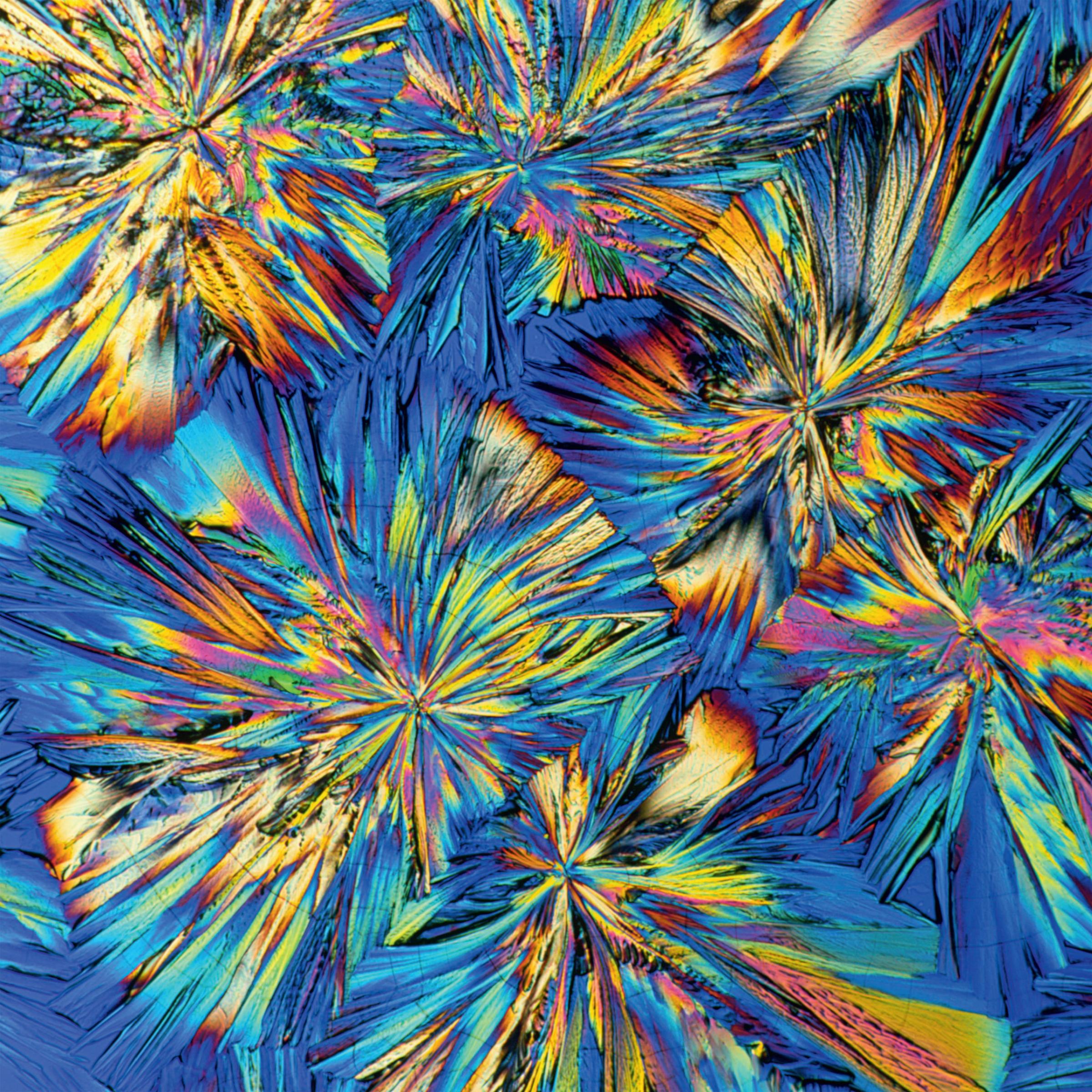

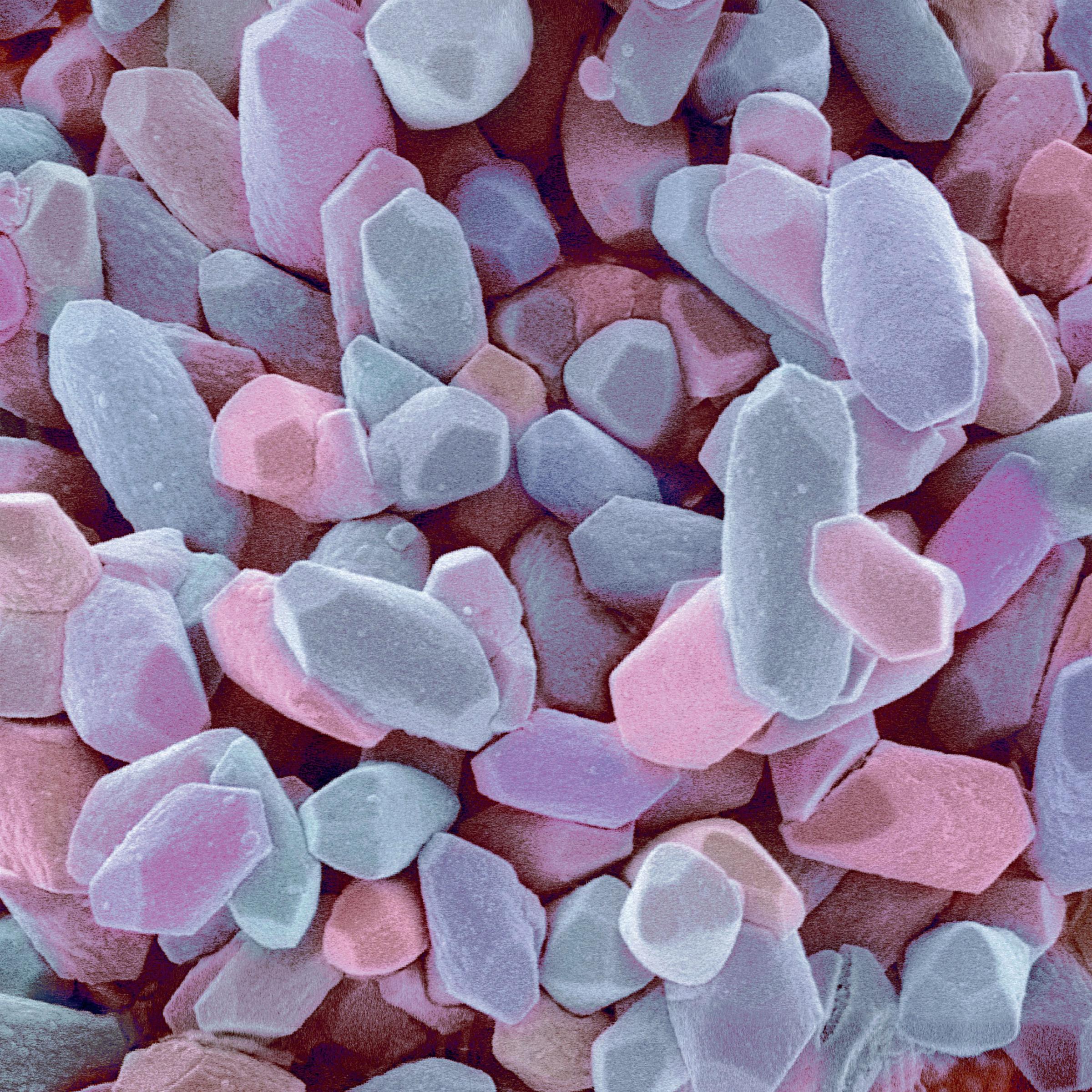

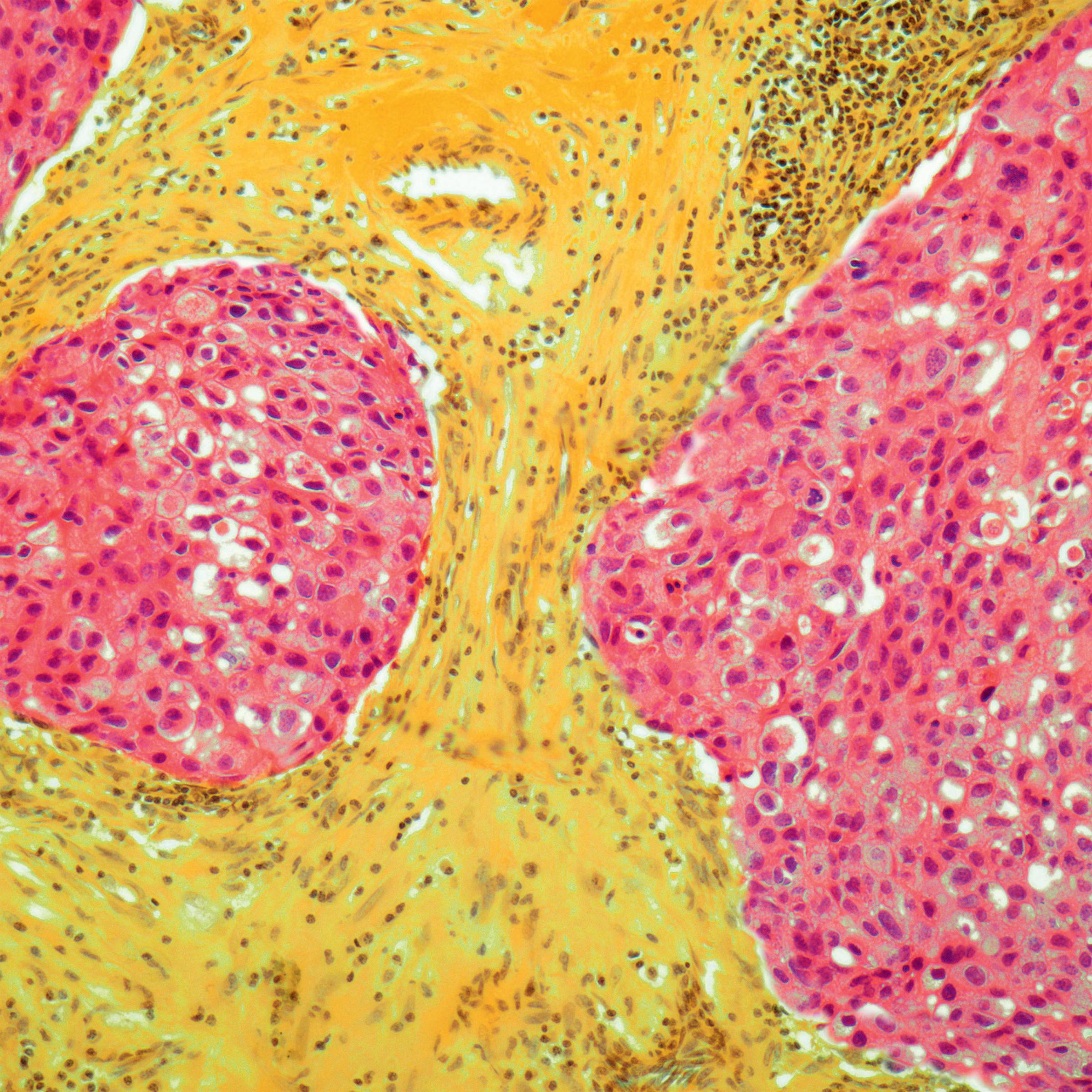

See the Human Body Under a Microscope

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com