Ego is cunning and hides even in humble places. An old Jewish joke tells of three scholars standing in front of the congregation on Yom Kippur. Each is beating his chest and crying loudly “I am nothing! I am nothing!” The lowly ritual director, standing in the back and watching the learned men, assumes this is how repentance is properly done. He begins to beat his chest and cry, “I am nothing!” One of the scholars turns to the other and says, “Huh—look who thinks he’s nothing!”

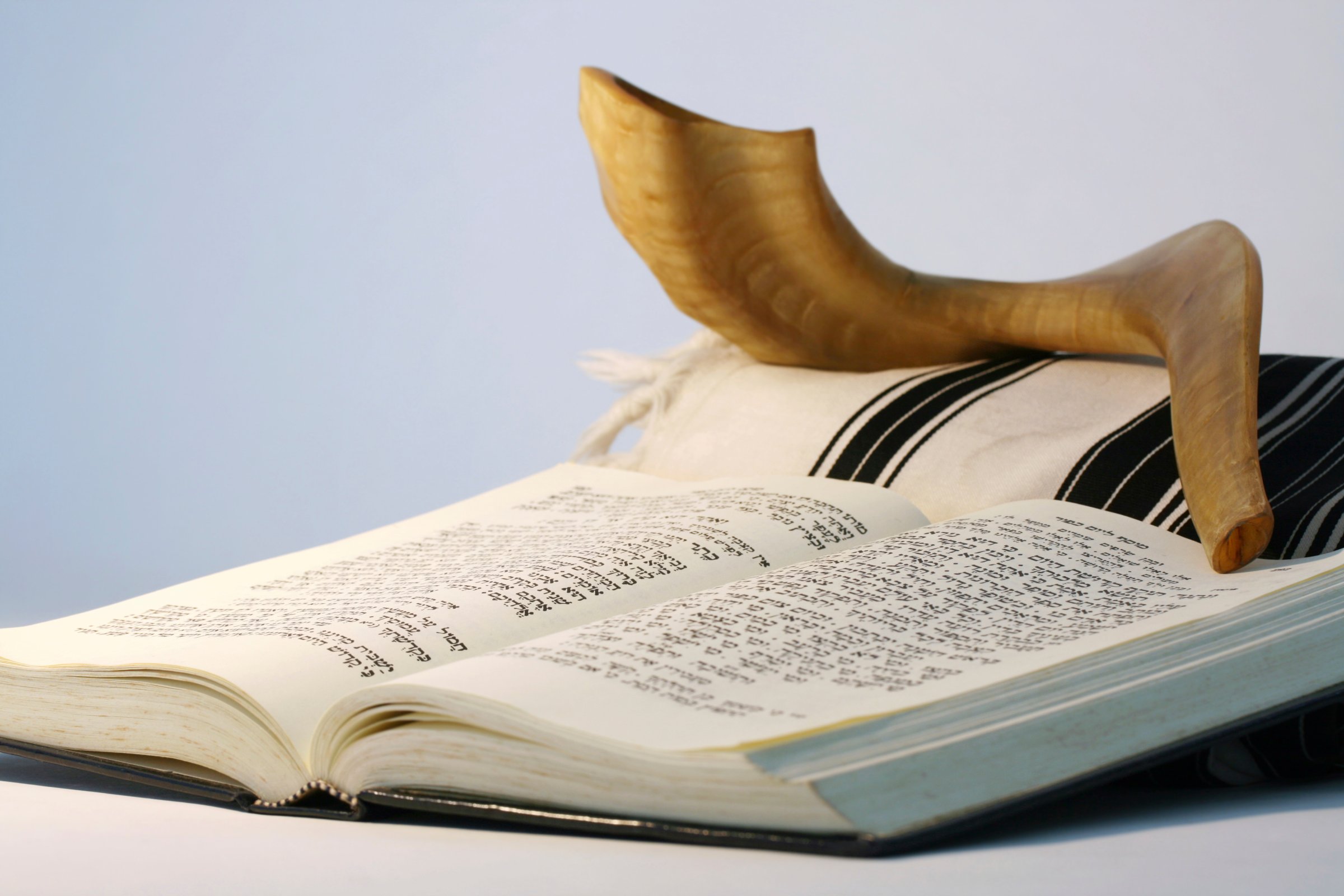

Pride hiding behind humility reminds us that Yom Kippur, observed this week, is based on a culturally unfashionable assumption. We are not deeply pure, enlightened creatures. We need not only follow our hearts to discover what is good. Rather, we are split, flawed human beings who must learn over and over again how to choose what is good and right in a world that often misleads us—when we are not simply misleading ourselves.

Judaism does not believe in original sin; it believes in moral dualism. People have both good and evil inclinations. One of the attributes of an evil inclination is to make itself appear good. People do harm in this world with a shiny conscience. Only later do they discover, if they ever do, that what they thought good was not. How many parents have done things out of love for children that proved to be mistaken or hurtful? How often do we look back and discover that our actions were unwelcome, unkind or self-deceiving? The world is complicated, mistakes are common, ego is subtle, and goodness takes work.

In synagogue on Yom Kippur, Jews recite a long list of sins and confess to each in the plural. We, as a community, have committed these sins. They are listed in alphabetical order. It is a curious choice, since we don’t sin alphabetically. One sage comments that although there is no end to sin, there is an end to the alphabet. Judaism assumes that wrongdoing is a constant accompaniment of our days. Sin knows no season; although Yom Kippur culminates the Jewish month of repentance, there is a confessional section to regular morning prayer all year long.

The enumerated sins of Yom Kippur prove revealing. There is no listing “for not listening to my heart” or “for not following my dreams.” But there is a confession “for those sins which I committed both wittingly and unwittingly.” The tradition recognizes that we carelessly entangle our hands in the heartstrings of others, hurting and wounding. We are imperfect. We may have a spark of the Divine, but we are not God. To believe that we are creatures of lightness and sweetness is a better indication of insensitivity than enlightenment.

Judaism holds the playground theory of morality. If you believe people are naturally good, visit a playground. There you will see human nature in its joy and goodness, but also in its narrowness and cruelty. Children need to be educated out of unkindness—taught to share, to sympathize, to help. The world is not solely a place of unfolding, it is a place of hard won soul-growth.

Jews confess in the plural because we are all interconnected, and we must all take responsibility for one another. We beat our chests out of contrition and also as a kind of Jewish defibrillation—we are trying to awaken our better selves. To shape the soul God has given us takes time, awareness and a great deal of effort. But when you are given such a gift, how could it demand anything less?

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com