What Steve Rannazzisi and I share is the fact that we were not in Two World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001. The comedian recently admitted to lying about escaping the building that day. My failure to be there was a mistake—I overslept and was late for my job as a financial editor on the 57th floor when the terrorist attacks began. It was also in those first moments where my own, more modest, performance career began—not because of that day, but despite it.

In the hours after the collapse of the towers, the trees and sign posts on my block in Manhattan were plastered with “missing” posters showing the faces of people my own age who had gone to work that day and were never going to go home. Many were not—as the signs so innocently hoped—missing, they were gone, and I was lost in the magnitude of their absence.

I would spend years of my life suspended in that state of penitence unable to move—why did I get to go on when so many fathers, mothers, husbands, wives and others did not? The only answer I could ever come to was that there was no answer, and that I had to reinvent and keep moving. The following 14 years have been a long, slow climb out of that state for fear and self-recrimination, but it’s been an upward climb.

One of the dreams that haunted me in those years was a recurring nightmare about being chased through an abandoned building being dosed with gasoline. So naturally when I was offered the chance to learn to eat fire, I jumped at it.

It sounds strange, but part of my healing was the search to find ways to turn negatives in to strengths. With that and a handful of other sideshow skills, I named myself the Lady Aye and began to appear in burlesque and variety shows around the city. My stage persona was designed to be everything I felt I was not: confident, sexy and fearless. It was a part I came to love playing and one I continue to hone on stages across the country, in small TV parts and anywhere else I can ply my trade. It was healing, it was fun, and it was exactly what I needed to fulfill my need to make my life mean something.

To make an audience laugh, to further an art form I love, gave me happiness, purpose and a much-needed sense of peace, so I really understand the drive to have those things as a performer. What I don’t understand is the need to have it so badly that you would use other peoples’ pain to get it.

Performing is a powerful experience for both the performer and the audience, so much so that my 9/11 experience is something I’ve rarely talked about onstage. It’s certainly there with me; it forms me, and it strengthens me, but it doesn’t entirely define me. I am here as an act of defiance to that darkness, not to flaunt it as a resume builder or something that makes me unique.

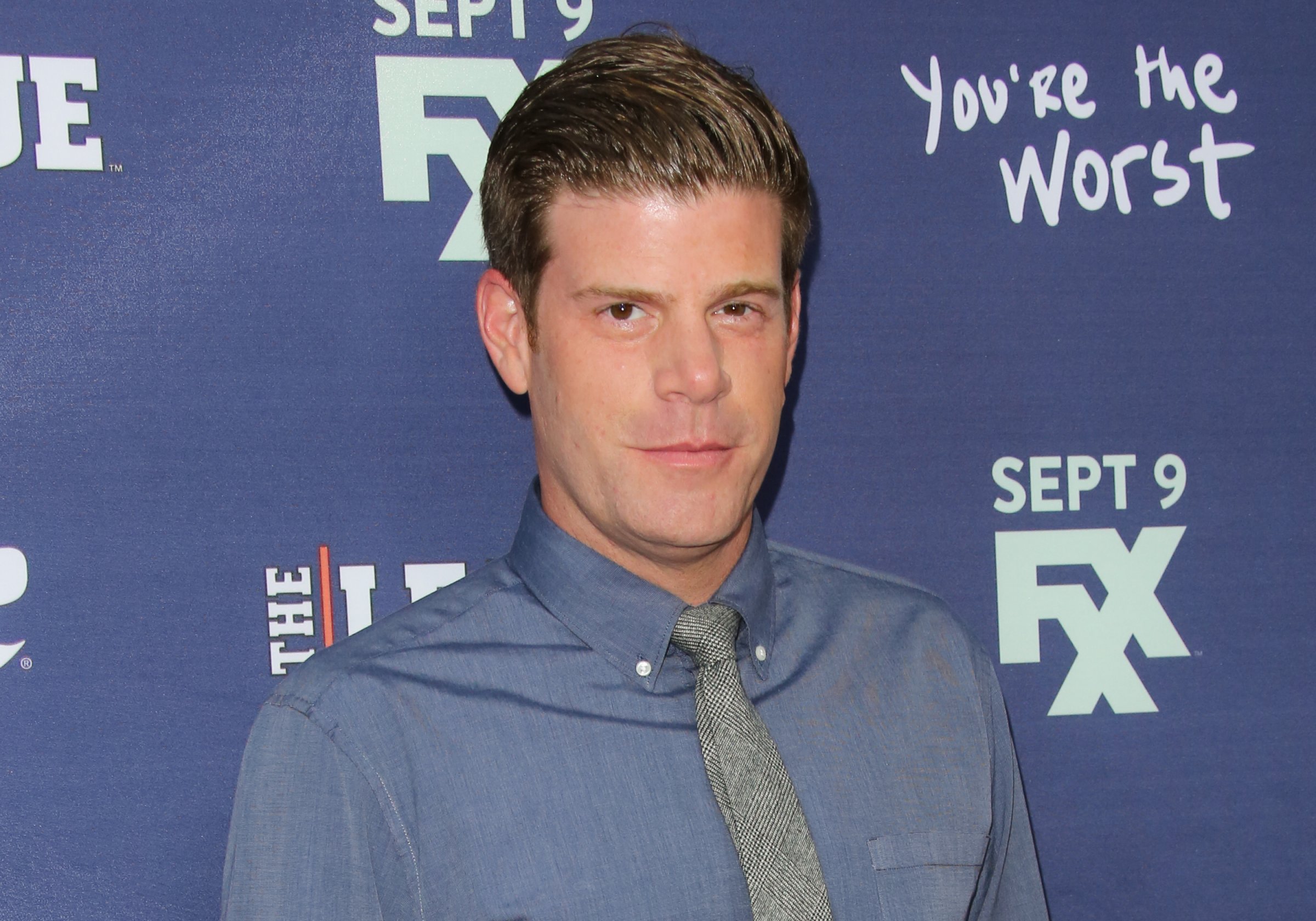

Rannazzisi’s lies are so ridiculous and offensive that my friend Eddie McNamara quipped that Rannazzisi is using it as “tragedy Woodstock.” As a former Port Authority cop tasked with cleaning up the World Trade Center site, and now a chef and author, he gets how absurd it is to want that distinction for your own.

If we laugh about it now, it’s because we cried about it before. For us, and for thousands of others genuinely changed by the experience, it’s our story to do with what we can. It’s our story to tell.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com