As California voters head to the polls this Election Day, one of the propositions on their ballot will be a question with decades of history and conflict behind it: Should the state make it easier for schools to offer bilingual education for students?

The question is a relatively narrow one, but bilingual education has long been an indication of a larger conversation about immigration and language in the United States. Though the subject has not provoked much conflict during the general election season, it was a major point of conflict during the Republican primaries. Donald Trump blasted Jeb Bush for speaking Spanish on the campaign trail, Marco Rubio responded that campaigning in Spanish can be the best way to reach Spanish-speaking voters and Carly Fiorina mistakenly said that English was the official language of the United States.

It’s not, though naturalized citizens do have to be proficient in it.

That link between citizenship and language ability has existed since the early 20th century. In 1905, on the order of President Theodore Roosevelt, a commission on naturalization issued a report that recommended—among other tweaks due to the increased volume of, and resistance to, immigration—making English language ability a prerequisite for becoming a citizen because “if he does not know our language he does in effect remain a foreigner.” The following year, after much debate, it became a requirement for new citizens to speak English. In 1950, as part of a Cold War-era security push, it became necessary to read and write English as well, with allowances for age and ability.

Those same requirements are still basically in effect today; the subject that tends to come up for debate today is whether English should also be required for legal residence short of citizenship (something Marco Rubio has long supported). But, for decades, bilingual education was the ground over which activists fought.

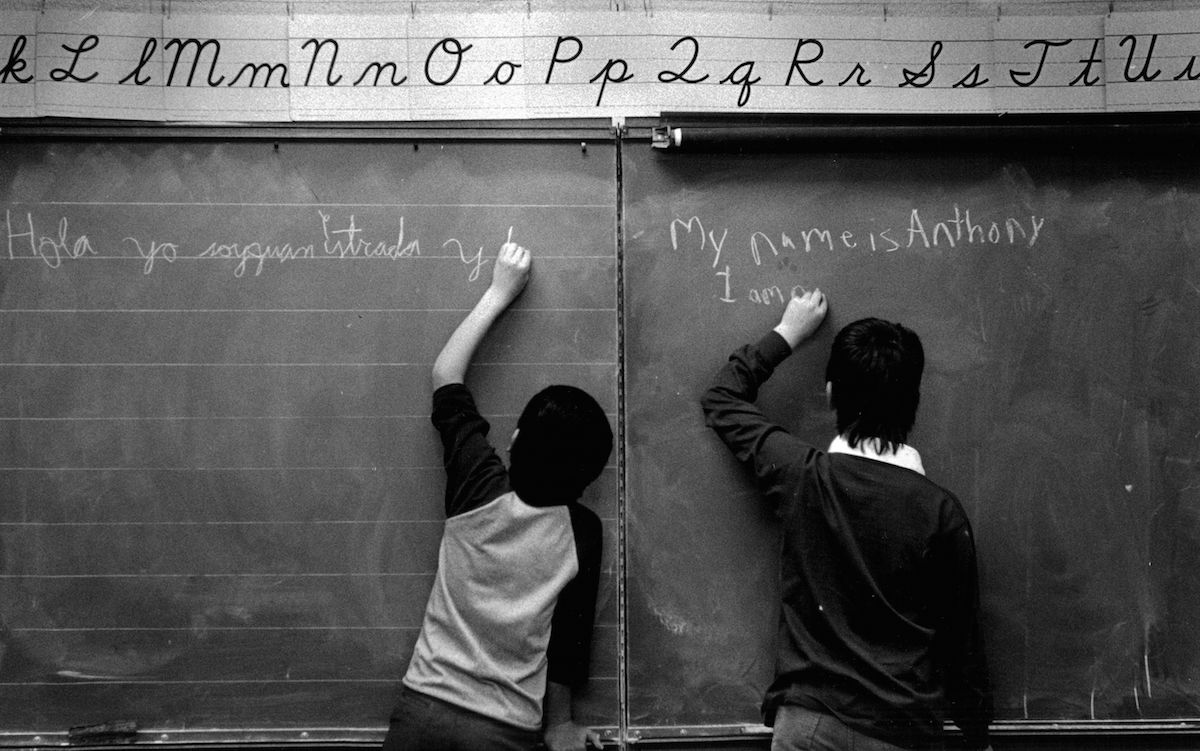

In 1968, Congress had passed a law, the Bilingual Education Act, designed to help young immigrants who were falling behind academically. The idea was that they could, on a voluntary basis, study other subjects in their native tongues while they worked toward English proficiency. The law provided funding for schools that wished to develop programs to do so. That ideal of bilingual education was strengthened in 1974 in the Supreme Court case Lau v. Nichols, which found that it was discriminatory for the San Francisco school system to fail to properly educate students who spoke Chinese. (After that ruling, the 1968 law was amended to be more specific in its requirements.)

By 1980, according to a TIME report on the then-burgeoning debate over whether those bilingual programs were the right use of education funds, about a half million children benefited from the federal program. By 1985, it cost over $350 million a year to run the programs.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

As an anti-bilingualism TIME essay pointed out in 1983, clumps of foreign-language speakers had long found their own solutions to the need to educate children who couldn’t learn well in the language of the school—thousands of Ohio students were educated in German around the turn of the 20th century, for example. Modern bilingual education, on the other hand, was seen by some as not a stepping stone to acculturation, but as a way for new immigrants to remain separate from the rest of the population. Many 1980s supporters of the English-only movement—like Walter Cronkite and Saul Bellow—argued that they were happy to support immigrants, but wanted to avoid a situation in which language served to divide rather than unite. Supporters of bilingual education, on the other hand, saw the loss of support for the programs as part of a xenophobic and racist trend, which spawned ugly treatment of those seen as outsiders.

California was particularly fraught territory, as large Chinese- and Spanish-speaking populations made the debate highly visible and highly emotional.

In 1986, the state made English its official language. California was in the minority at the time, but the majority of states went on to pass some version of such a law. (A stricter version, which actually limited the way government officials could talk, however, was struck down on free-speech grounds.)

It was perhaps no coincidence that the 1980s and ’90s saw bilingualism become a political problem, complete with a lobbying group. English-only proponents of the 1980s and ’90s tended to turn again and again to the same example of the problems with bilingualism: Canada. Canada had little to teach the United States about large-scale immigration by Spanish speakers, which was the heart of the issue south of the (northern) border, but Canada had problems of its own. During the 1960s—within memory for those who were active in politics in the early 1980s—the movement for French-speaking Quebec to become a separate country gained steam. By the end of the 1970s, Quebec’s language problem was “a political time-bomb” that threatened “the unity and perhaps even the survival of Canada,” per TIME. Throughout the ’80s, it seemed plausible that a peaceful nation right next door might actually be split in two because it couldn’t accommodate multiple languages and the multiple cultures they represented.

Except that didn’t happen.

By the early ’90s, a separate Quebec no longer seemed realistic. Still, the specter of bilingualism had already been raised in the United States. Language had become a political issue, and it would be hard to take that back.

In 1998, California approved Proposition 227, dramatically shrinking the scope of bilingual education in the state. That’s the measure that’s up for possible roll-back this year—which would perhaps signal that the English-only moment of the late 20th century is making way for something new.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com