As refugees and migrants from Syria and elsewhere continue to flood intro Europe, much of the conversation about their eventual destinations has focused on which European nations are welcoming them and which are not. The global problem however, is not limited to resettlement in Europe. Some American states are already taking a significant number of refugees, and President Obama said last week that he hopes to allow 10,000 more in the coming year.

Though Obama’s announcement has been criticized as “reckless” by some who see it as a security risk, the 10,000 Syrians who might be resettled on American shores is actually an extremely small number in historical perspective.

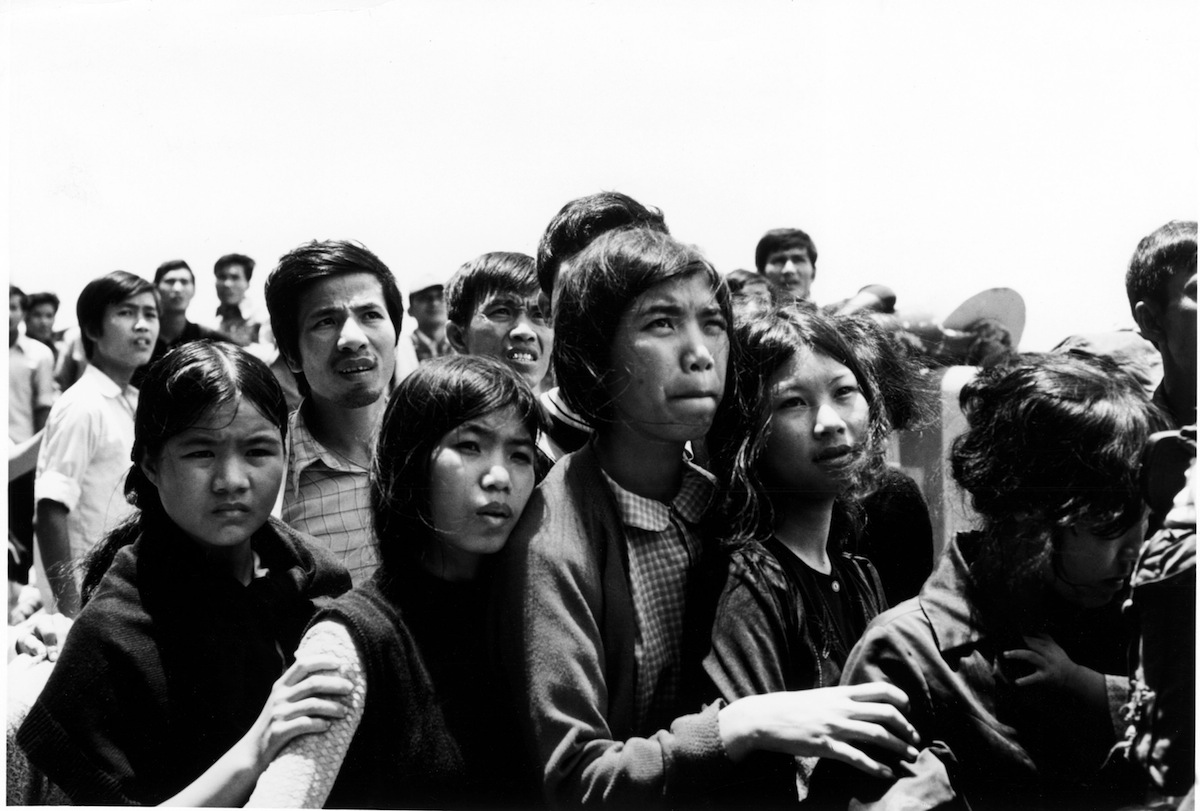

Take, for example, the Vietnamese people who came to the U.S. after the 1975 conclusion of the Vietnam War—a number estimated at 120,000 that year. A Gallup poll at the time showed that only 36% of respondents thought they should be brought to the United States. The refugees came along with fear that they would “steal” jobs or, conversely, be a burden on the system if they were unable to find jobs. In addition, the Cold War was still raging, and many feared the future political leanings of the country’s newest residents. Some also posited that Americans, desperate to forget the war, simply dreaded seeing Vietnamese faces on their streets.

Still, there was a widespread feeling that the country owed something to the people whose lives had been endangered by the American military’s actions in their country—and the refugees were already on their way.

They were processed in Guam before being brought to military bases in California, Arkansas and Florida. They were seen by doctors, fingerprinted by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, tested on their English and provided with a Social Security card. Then, if they could find a sponsor—an American, often a complete stranger, who would help them find a home and a job—they were able to begin civilian life.

The first wave of refugees were mostly professionals and elites who could get out right when the Americans did, and who many times were highly sought after by sponsors. (TIME profiled one Vietnamese couple, both doctors, who were supported by a Nebraska town desperately in need of a local physician.) Those who came in the later wave—precursors to the so-called “boat people” who would flee the region in the years to come—were more likely to be laborers, farmers and fishermen.

Just as is the case today, many worried that the new influx of people would pose a security threat to the nation. Each person was—per standard immigration procedure—supposed to get a security check. But, as TIME reported in May of 1975, “since the refugees left their pasts and their records in a country now occupied by the Communists, the check may simply slow down the flow of refugees all along the line, from Guam to the U.S., and force them to spend weeks in the camps.” The backlog in Guam quickly reached 50,000 people. Conditions were worsening as more and more refugees crammed into a tent city meant to house them for short stays only. As a result, it wasn’t long before INS reversed the decision to require the background checks for everyone, waiving the requirement for anyone who had worked for the U.S. government, was married to a citizen or was closely related to someone who was. By the end of the month, Congress had approved $450 million to help the refugees get settled.

And, by and large, it worked.

By 1979, TIME observed that, though the transition hadn’t necessarily been a smooth one, most of the Vietnamese immigrants who had come to the U.S. in 1975 had adjusted well. Employment was actually higher among that group than among the entirety of the American population, and the number who depended on the government for help was sinking. Nearly three-quarters of those 1975 families earned $800 a month or more, which is about $2,775 in today’s dollars. The Vietnamese immigrant population in the United States remains relatively well-off.

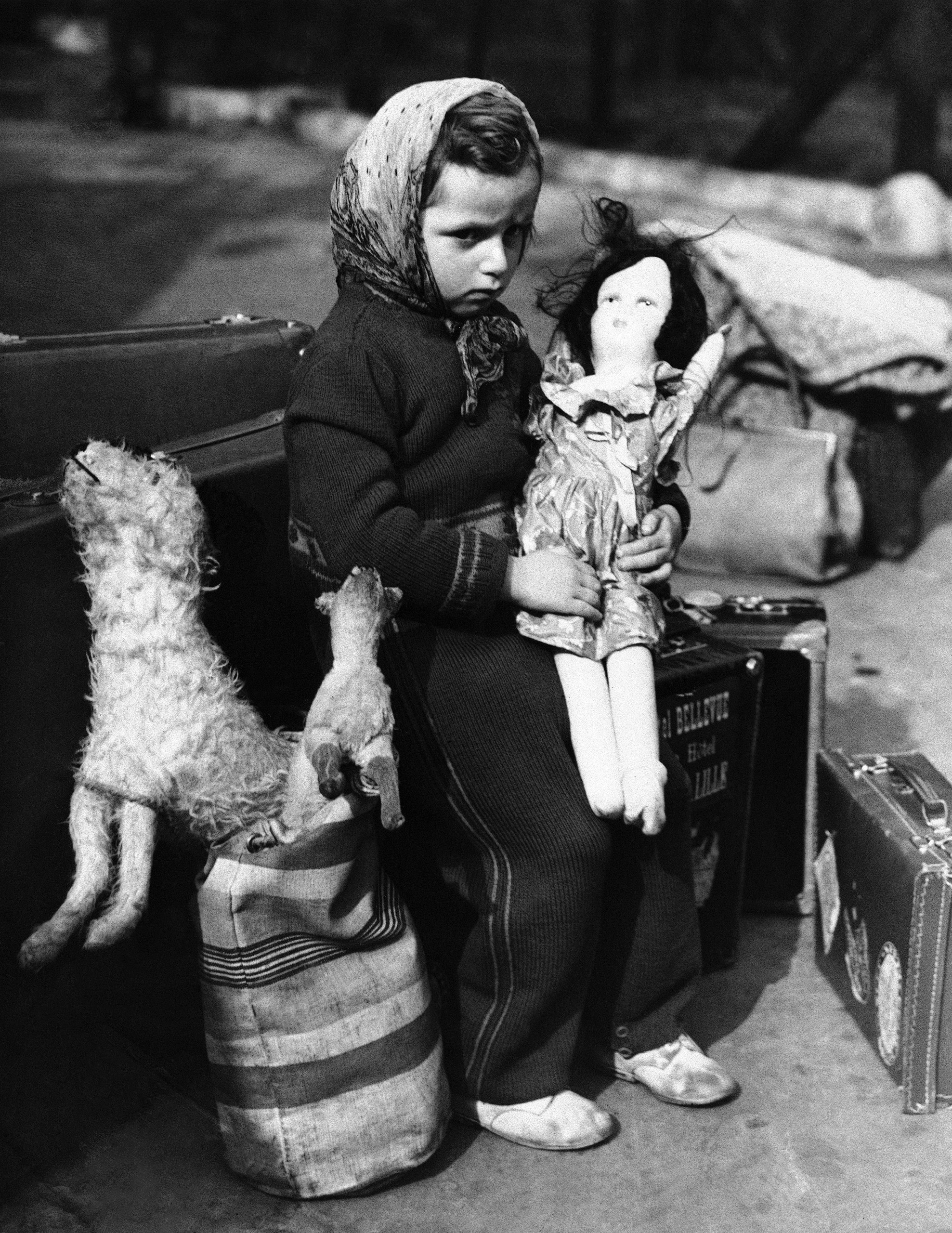

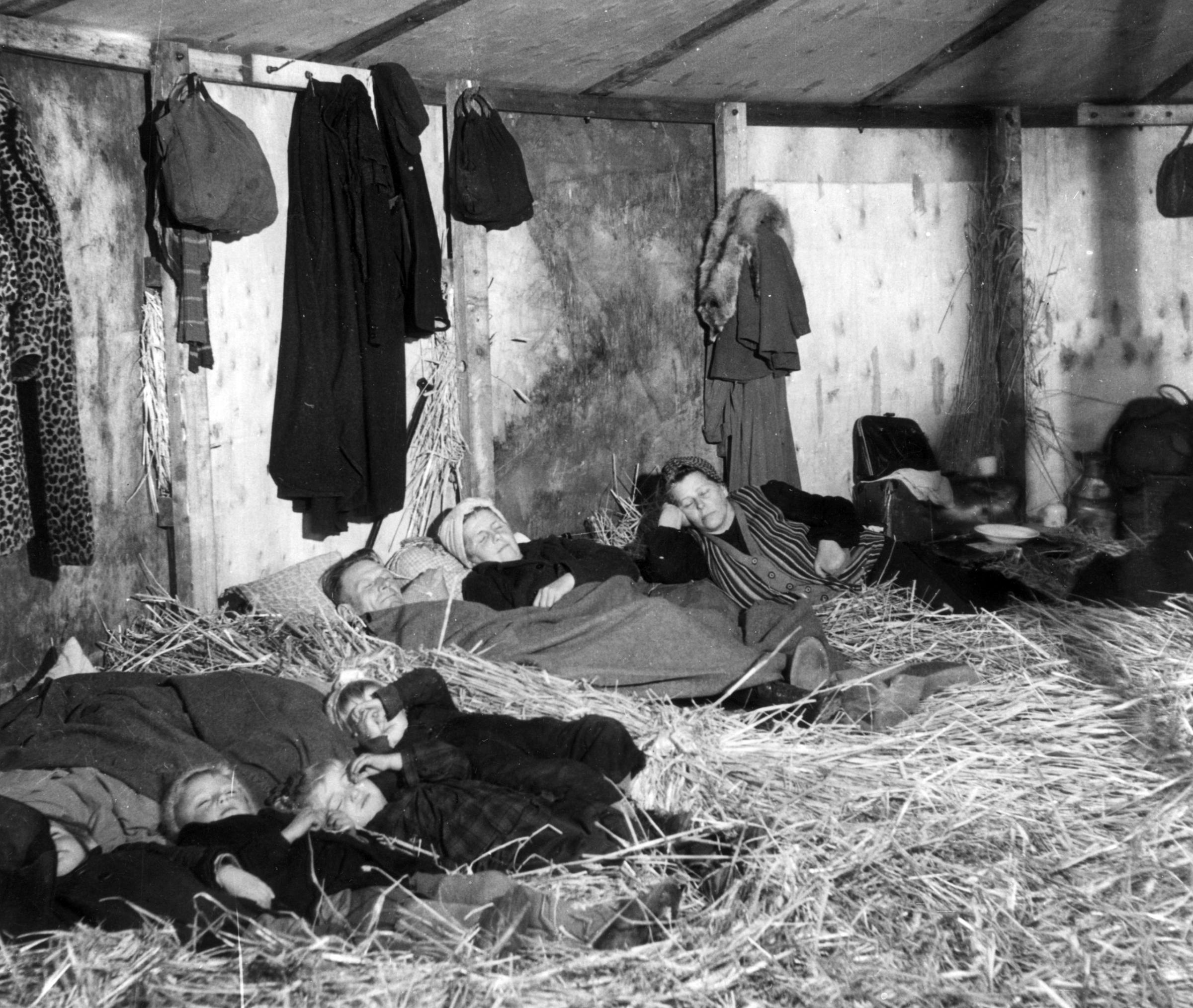

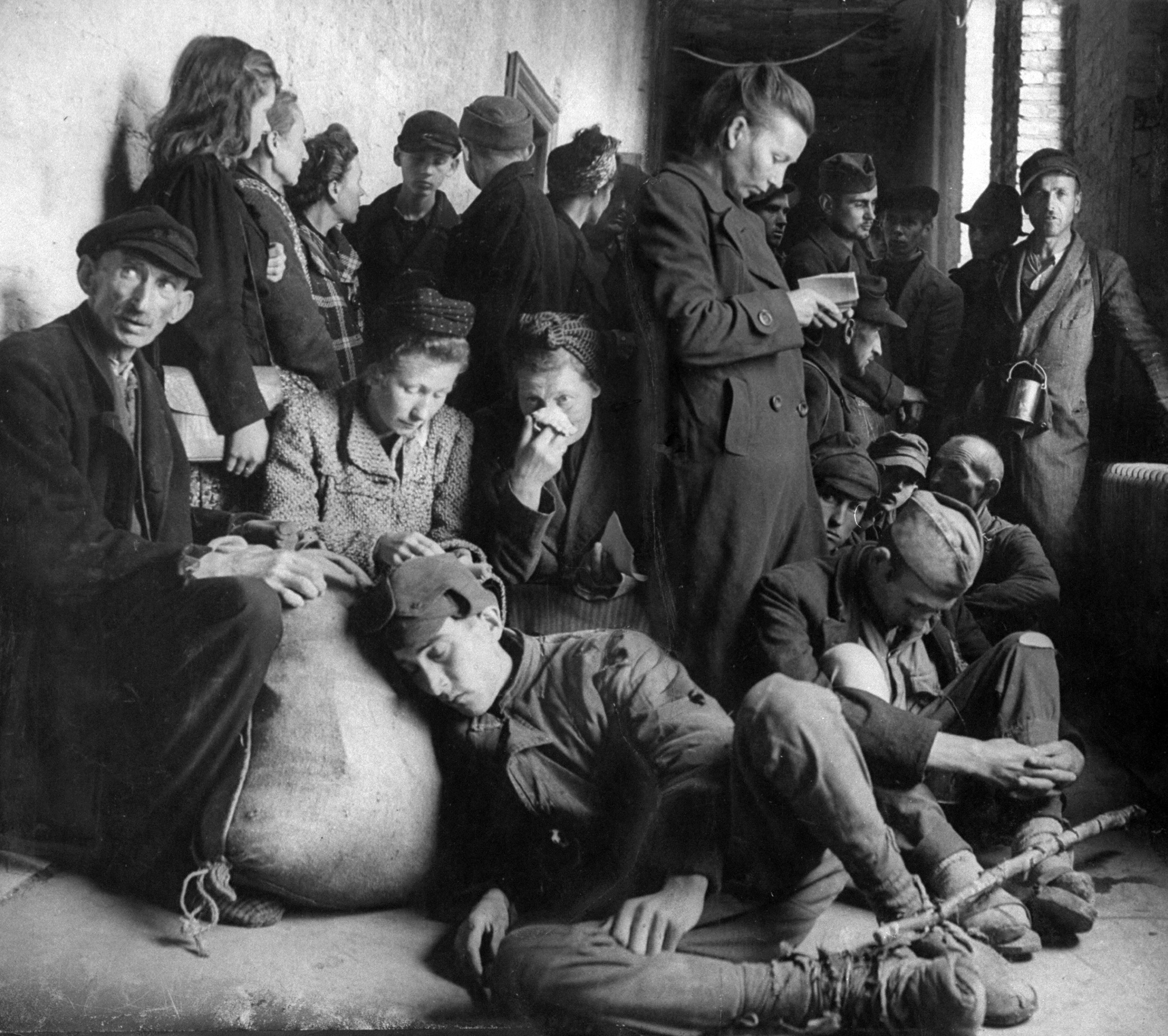

Despite the fears felt in 1975, the U.S. had easily absorbed those 120,000 refugees—twelve times the number of people currently being discussed. But, had they looked back a few decades, the Americans of the 1970s shouldn’t have been surprised. After all, 120,000 is a relatively small number too: as TIME explained in 1975, about 400,000 Eastern Europeans came to the U.S. after World War II and 650,000 Cubans were resettled, mostly in Florida, when Castro came to power.

Read more from 1975, here in the TIME Vault: A Cool and Wary Reception

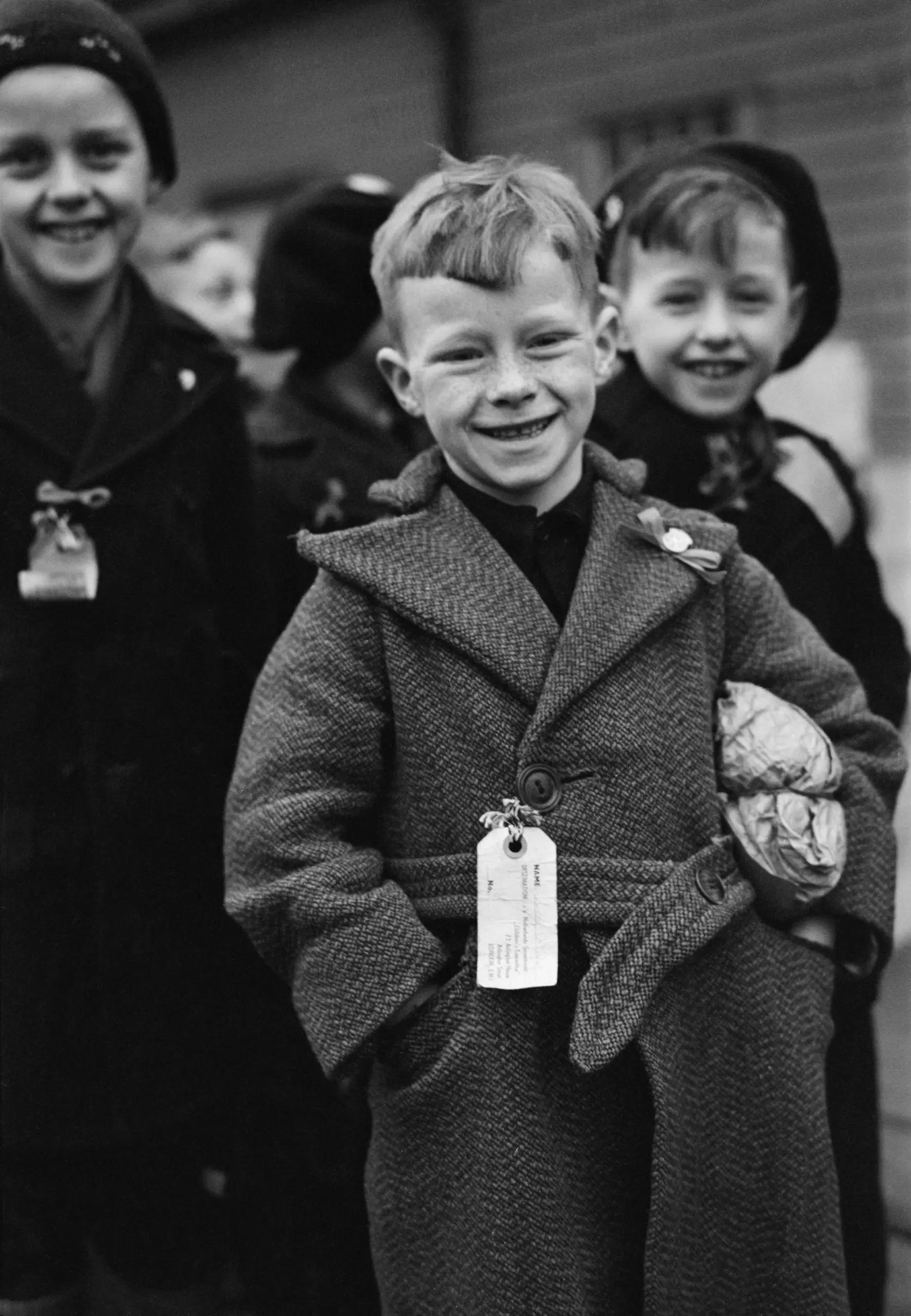

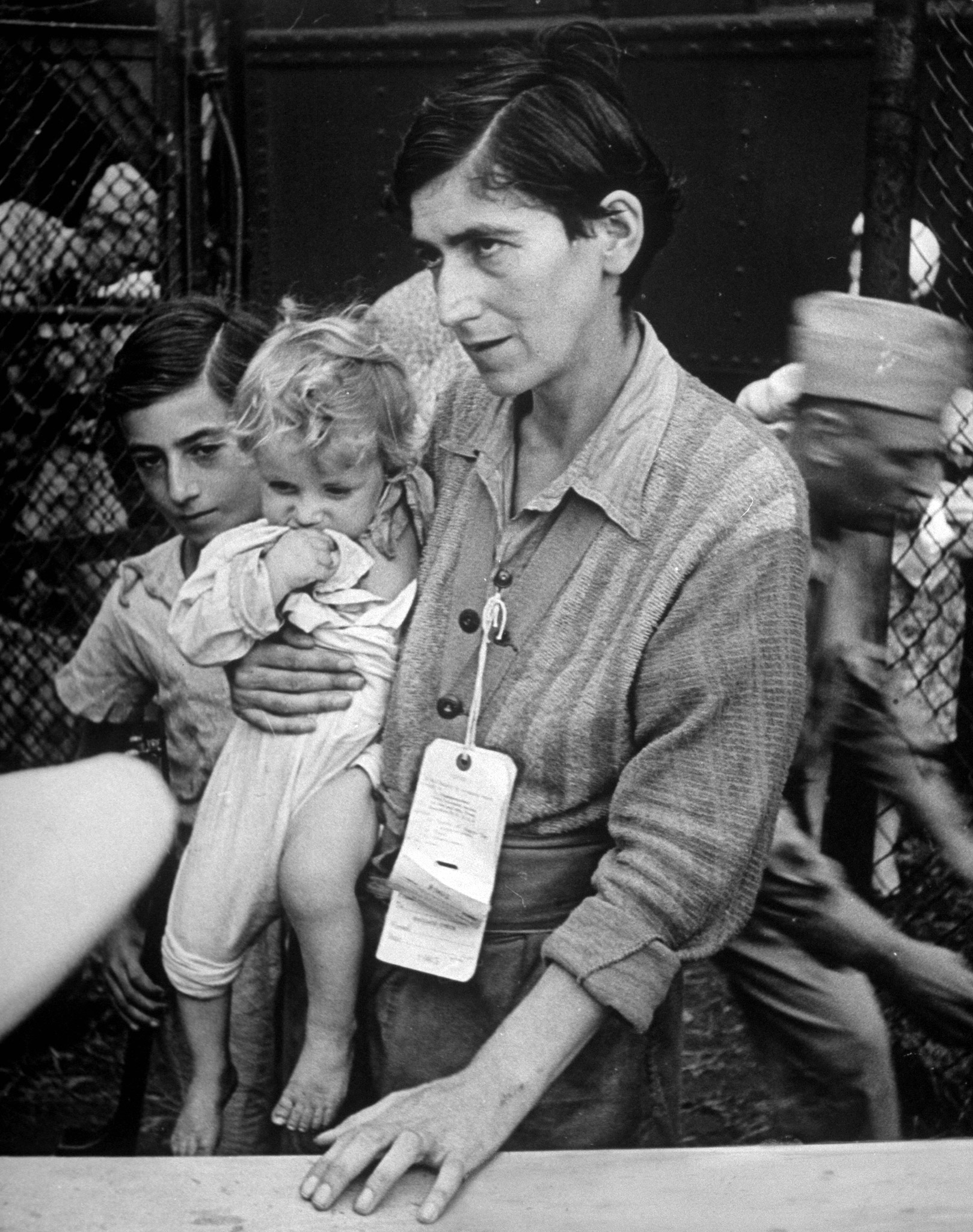

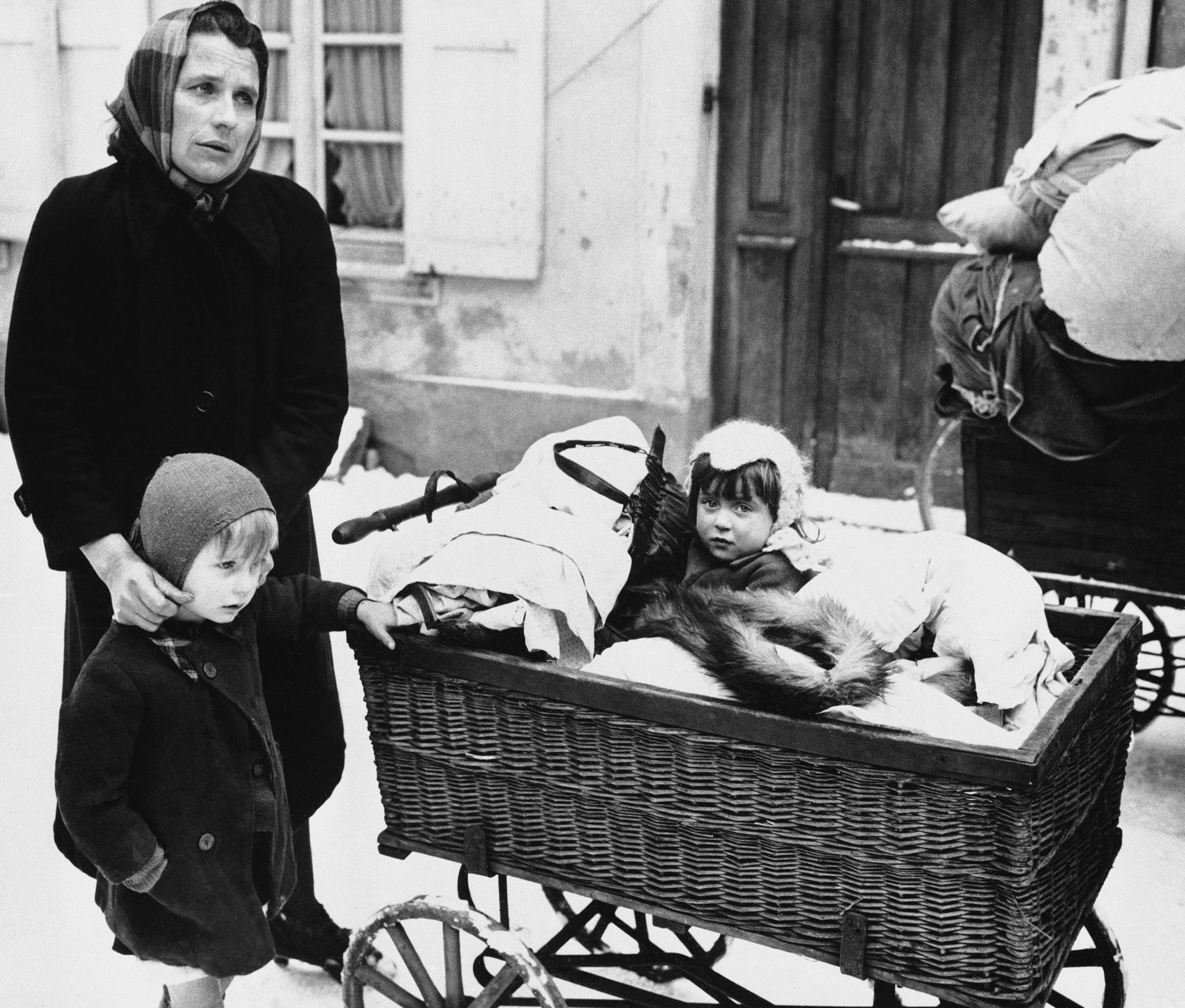

This Is What Europe’s Last Major Refugee Crisis Looked Like

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com