Syrians fleeing war are driven to board precarious boats to cross the Mediterranean. They crowd onto trains and climb mountains. They risk detention, deportation, and drowning.

There is growing evidence that the people dying to reach the shores of Europe are fleeing not only war in Syria, but oppression in other Middle Eastern states.

As pressure rises for European leaders to resolve the refugee crisis, critics are also asking why Middle Eastern governments have not done more to help the four million Syrians who represent one of the largest mass movement of refugees since World War Two. Much ire has focused on the relatively wealthy states along the Persian Gulf. According to a report by Amnesty International, the six countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council offered zero formal resettlement slots to Syrians by the end of 2014.

Read about changes to Time.com

Rights groups point out that those countries — Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) — with wealth amassed from oil, gas, and finance, collectively have far more resources than the two Arab states that have taken in the most Syrians: Jordan and Lebanon. The Gulf states are Arabic-speaking, have historic ties to Syria and some are embroiled in the current crisis through their support for insurgent groups.

“The missing linkage in this tragic drama is the role of Arab countries, specifically the Gulf countries,” says Fadi al-Qadi, a regional human rights expert in Jordan. “These states have invested money, supported political parties and factions, funded with guns, weapons et cetera, and engaged in a larger political discourse around the crisis.”

Supporters of Gulf governments contend that such criticism is unwarranted. The Gulf states have donated tens of millions of dollars to help Syrian refugees in places like Jordan. Saudi Arabia claims it has admitted half a million Syrians since 2011. Syrians are welcome to come, the argument goes, even if they are not legally registered as refugees.

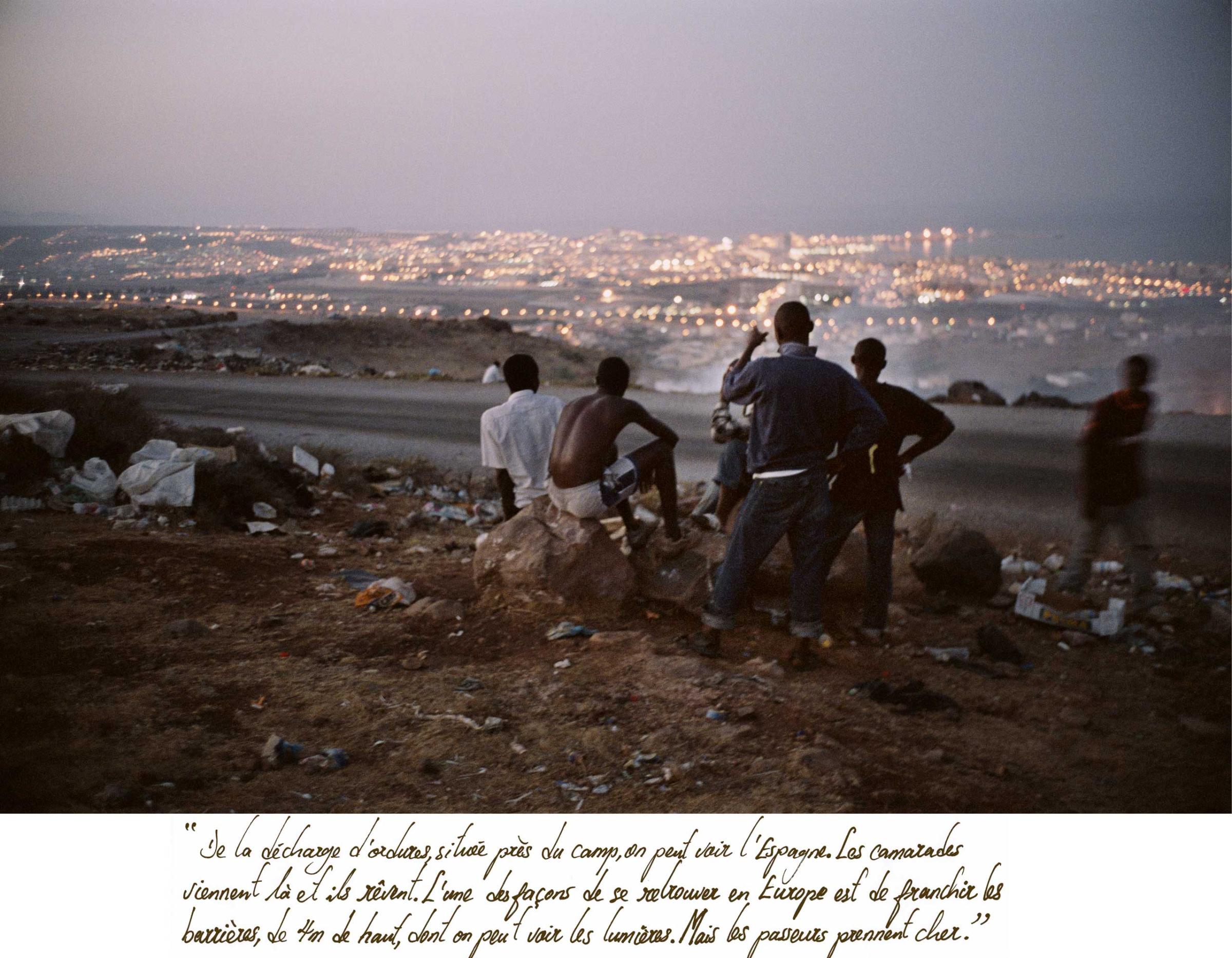

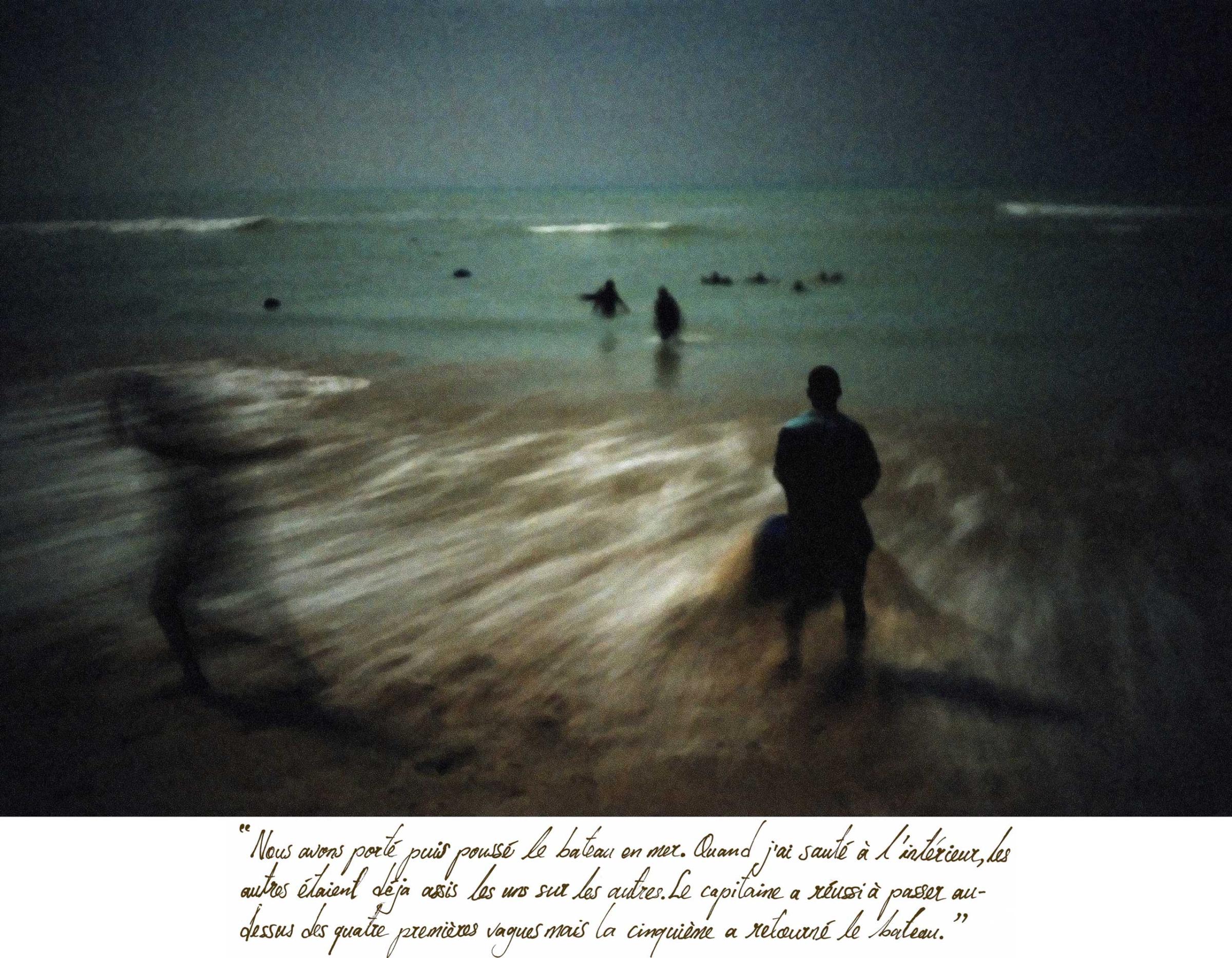

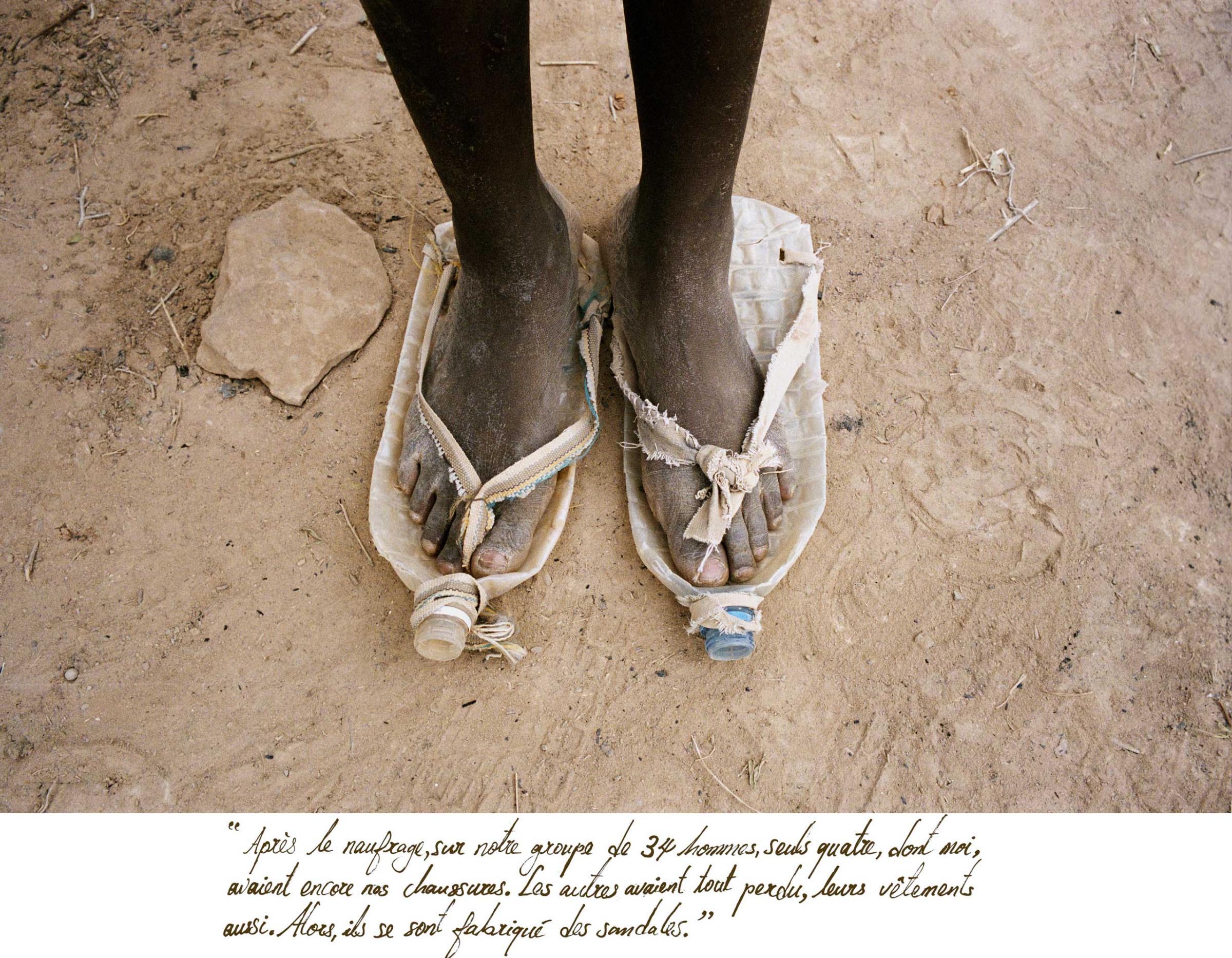

Photographers Aim to Put a Face on Europe's Migrant Crisis

Rights groups are not convinced. Visa restrictions make it difficult for Syrians to enter Gulf countries in practice, and even harder to stay. “These countries are not making clear, logistically and technically, to these people that your destination could be the Gulf,” says Qadi. “They have to make it clear. They have to announce it.”

The logic behind Gulf refugee policies is complex. In smaller Gulf states like Qatar and the UAE, foreigners already far outnumber nationals, a demographic balance that, for some, feeds feelings of anxiety tinged with xenophobia. In the UAE, foreign nationals outnumber citizens by more than five to one.

Elsewhere in the Middle East, Syrians fleeing the slaughter in their country often face a bleak landscape with few opportunities to work, attend school, reunite with their families, and start new full lives.

Lebanon has accepted more than 1.1 million Syrians, the most of any Arab state (Turkey has accepted approximately two million). That means that at least one in five people in Lebanon is a Syrian refugee. Lebanon forbids the construction of formal refugee camps. As a result, more than 40% of refugees in Lebanon live in makeshift shelters including “garages, worksites, one room structures, unfinished housing,” according to U.N. figures cited by Amnesty International. Many Syrians rely on aid agencies whose resources are stretched thin.

In Egypt, state repression is part of what is compelling Syrians to risk the sea route to Europe. Following the military’s overthrow of elected president Mohamed Morsi in 2013, Egypt demand Syrians apply for visas. Morsi’s Islamist government was sympathetic to the rebel cause in Syria, but the new military-backed regime is less sympathetic to Syrian migrants many more have been deported. Coinciding with a tide of Egyptian nationalism, Syrians reported being fired from their jobs, detained by police, and harassed by landlords.

Bassam al-Ahmad, an official with the Violations Documentation Center, a Syrian human rights group, said that tightening restrictions on Syrians’ entry across the region is helping drive the wave of migration to Europe.

“I cannot go to Egypt. It’s kind of like the circle became very, very narrow. In Lebanon it’s similar,” he says in a phone interview from Istanbul. “All of this pushes people to go to the sea. It’s like going to die, going to death.”

Inside Syria, the bloodshed continues, driving more and more Syrians to flee into the unknown. As a result of this carnage, Qadi says, most Syrians are facing a decision to stay or flee. That is the source of what is now understood in Europe as a refugee crisis. “The bomb is coming anyway, and it will destroy this house, and my kids will be gone,” he says. “Would I take another risk by trying to escape before the bomb comes? And go to the unknown? I think most Syrians are making that difficult choice.”

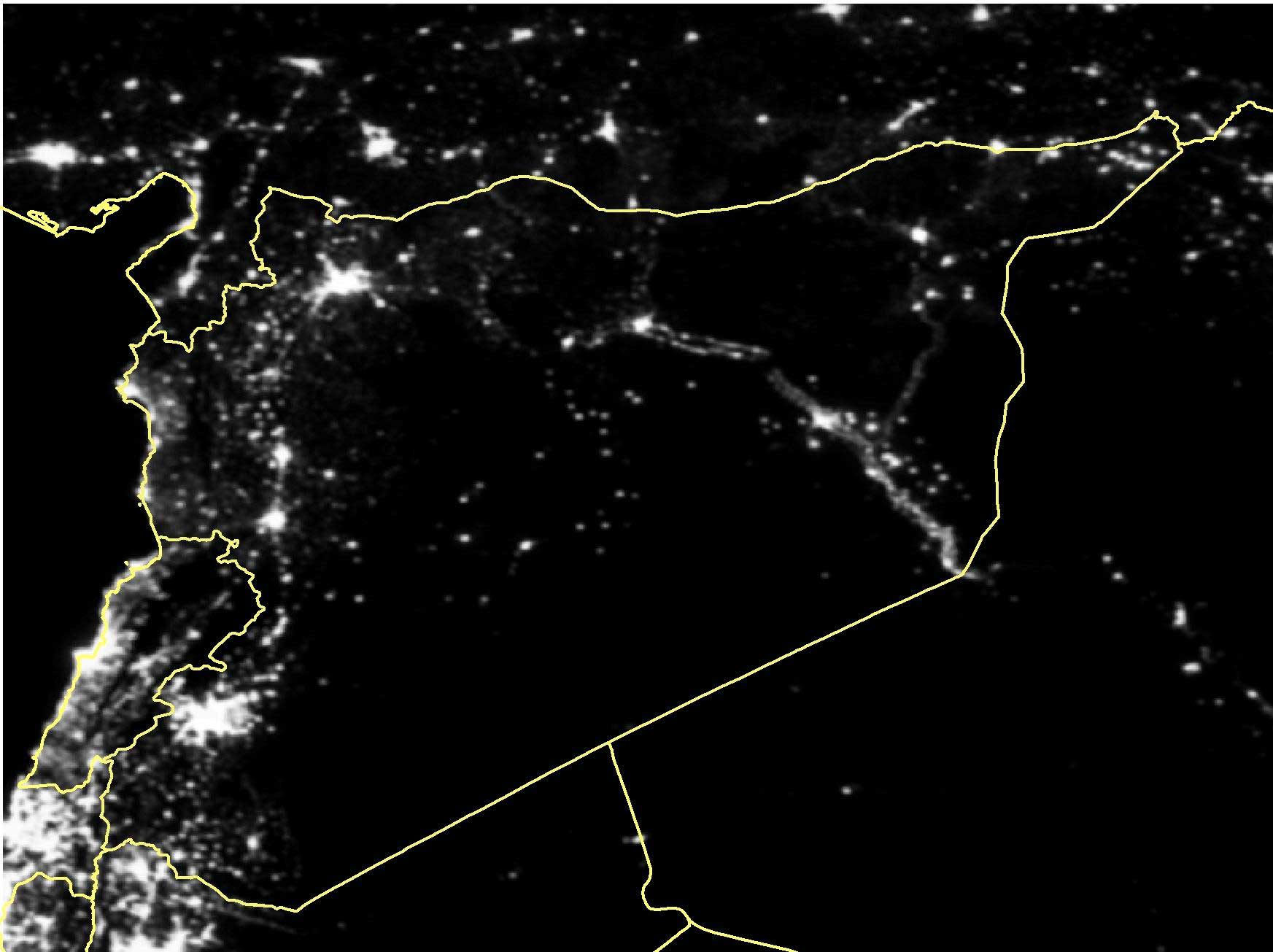

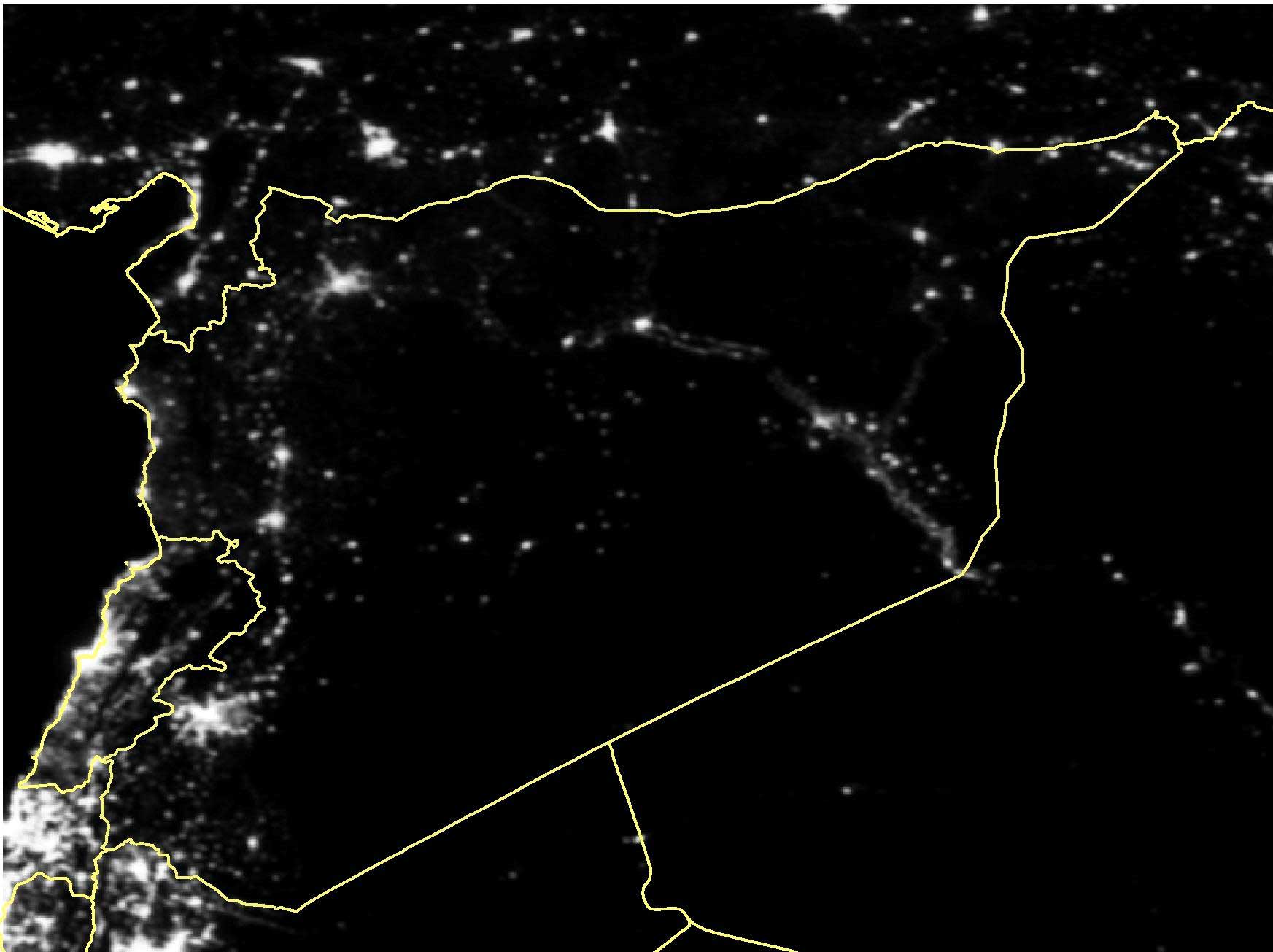

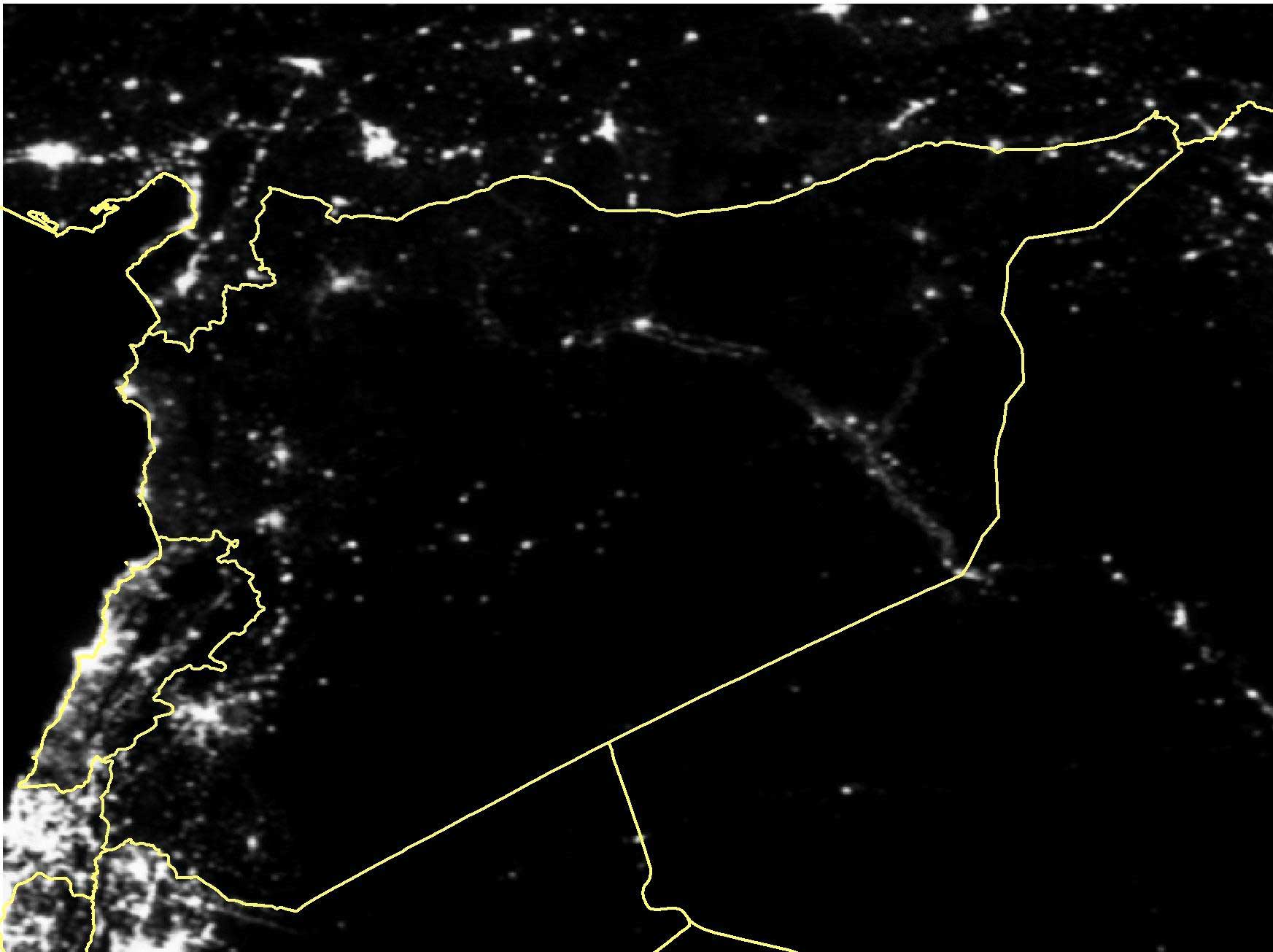

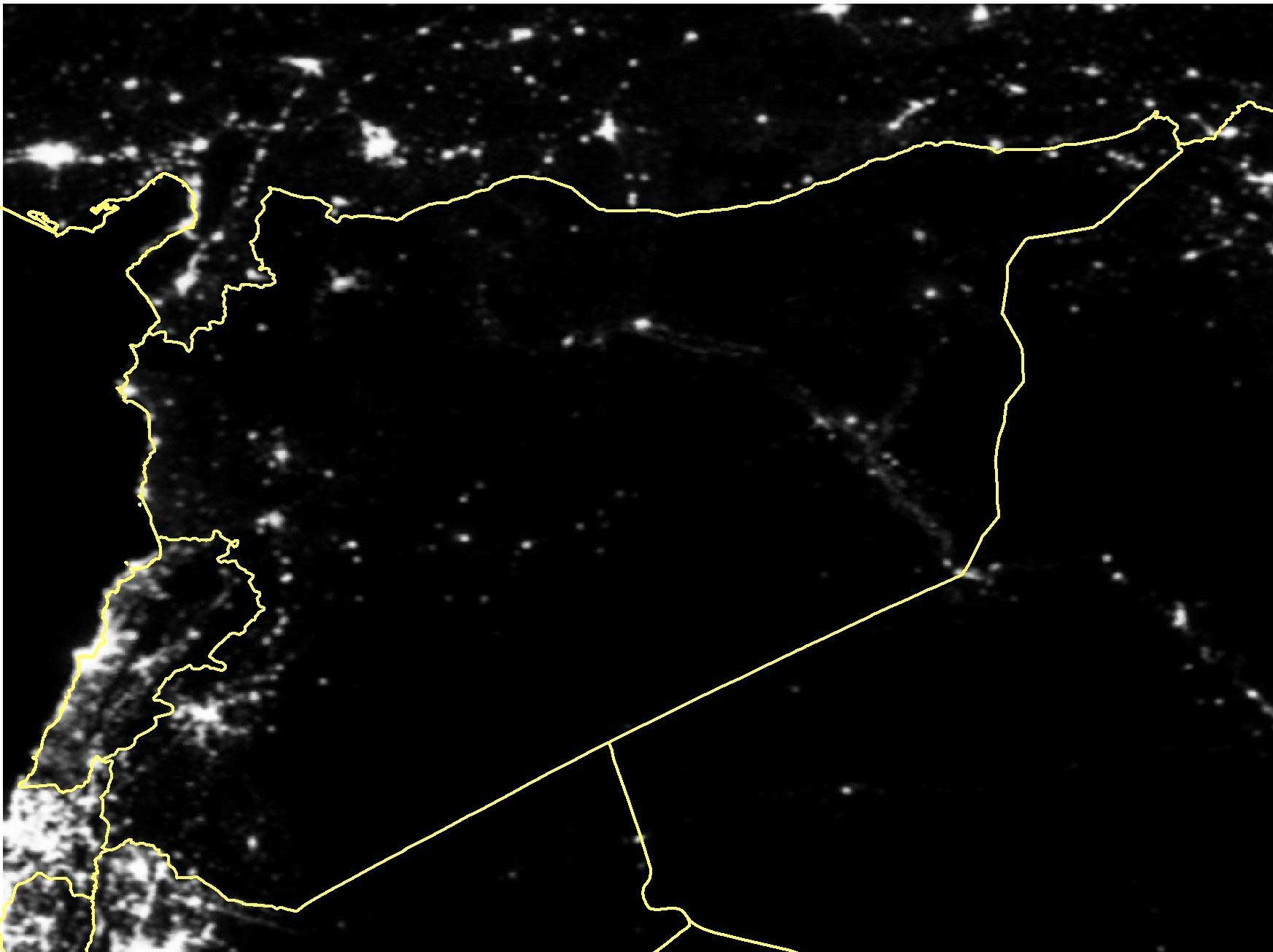

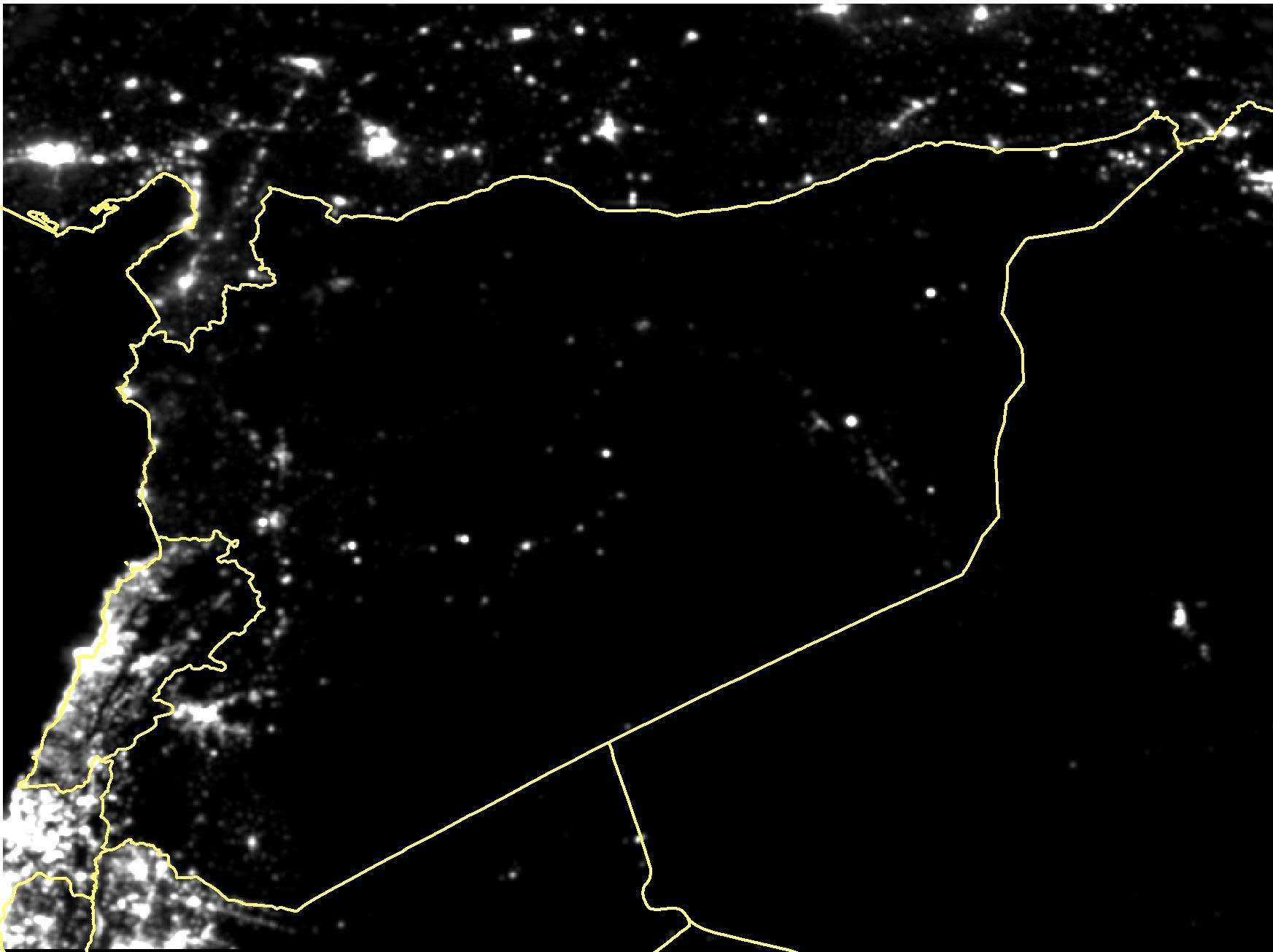

Satellite Photos Show Most of Syria Without Lights

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com