In recent weeks, all across Asia there have been countless ceremonies, somber and solemn, to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of the World War II in the Pacific. This titanic struggle officially came to a close on the battered, sunbaked deck of the U.S.S. battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay, with the Japanese military signing their surrender papers on Sept. 2, 1945.

Tokyo’s defeat is being marked today in Beijing, where a massive military parade commemorates the 70th anniversary of what is known as the Victory of Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War. Far away, in the sleepy rural town of Chiran, in Japan’s lush southern prefecture of Kagoshima, another, far quieter ceremony has been held. Its location? The little-known Chiran Peace Museum.

The museum, known locally as Tokko Ihinkan (or Chapel of the Thunder Gods), is located at the end of a long row of pretty white birch trees. Two white pillars at the entrance, and a gently arched grey-tiled roof, give the building the look of a chapel. The grounds are covered with white gravel and landscaped with scores of cherry trees, pensive pines and Japanese maples, the latter running deep red in the autumn months.

In fact, the Chiran Peace Museum is dedicated to Japan’s kamikaze pilots — the thousands of young men, most of them in their late teens or early 20s, who accepted certain death by flying their explosive-laden planes into approaching American warships, in the name of national honor. In the final months of World War II, these young suicide pilots were trained to destroy approaching American ships by flying directly into them.

In an attempt to boost morale, Japanese military commanders (themselves tucked safely away in bunkers in distant Tokyo) proclaimed the young pilots “thunder gods,” declaring that after the thunderous explosion of their airlines, the young men would become divine spirits. Japan’s imperial command also bestowed on the fliers the term kamikaze — divine wind — a reference to the fierce typhoon winds that saved Japan from attacking Mongol fleets in the 13th century.

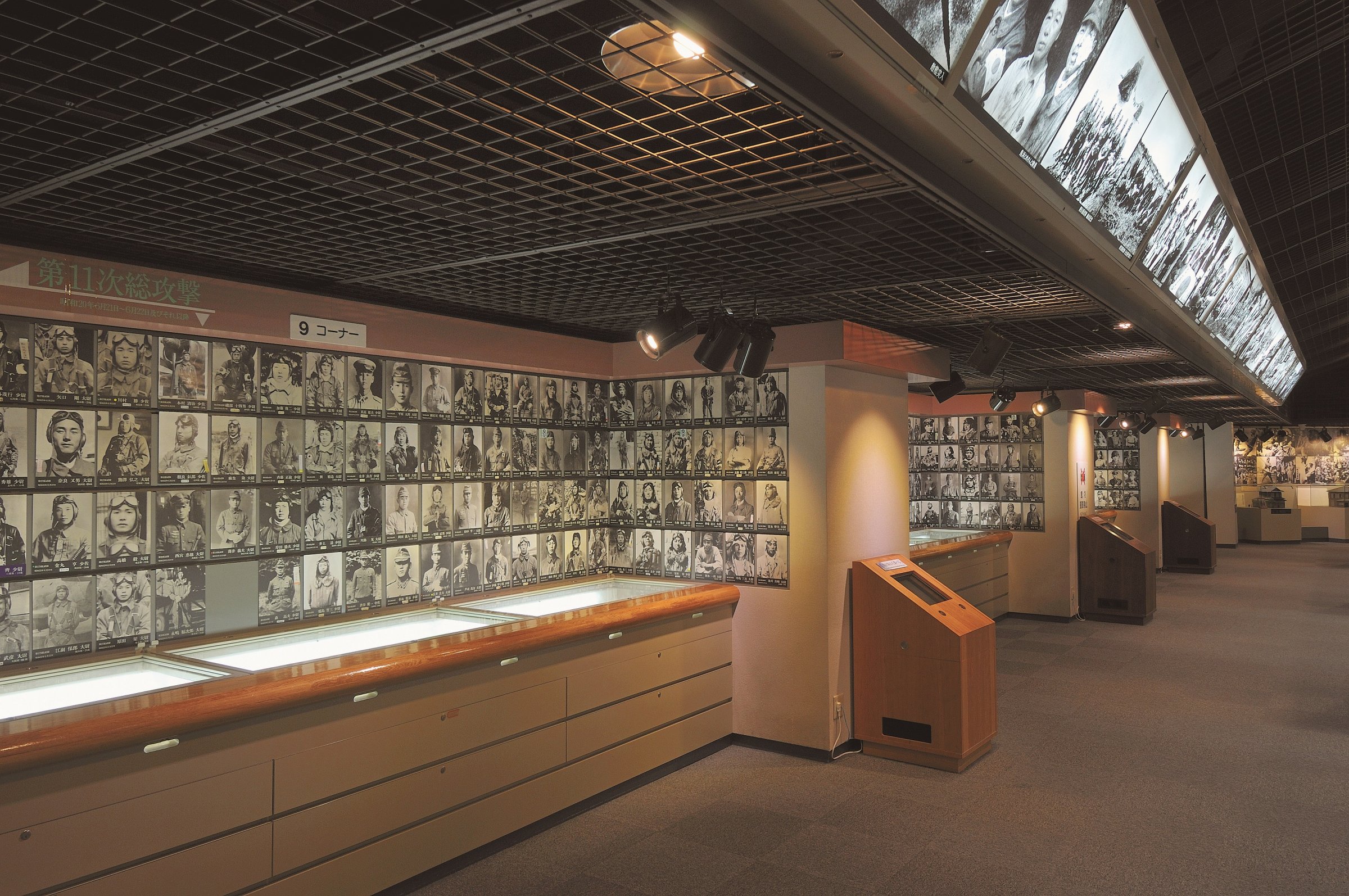

Inside the museum are a number of World War II Japanese aircraft. But what catches the eye of most visitors are the many spotless display cases that hold such kamikaze artifacts left behind: notebooks, goggles, diaries, wristwatches and handmade dolls given to the pilots by female relatives. Lining the museum’s walls are hundreds of black-and-white photos of the young pilots, each with a name and date of death, in the order that they died. One of the most poignant photos shows five fliers holding a puppy. While the labels are in Japanese, foreign visitors will have no trouble reading the emotion in the eyes of the pale young men as the gamely pose for a last toast before climbing into what were essentially their flying coffins. These are no wild-eyed ISIS killers.

The aircraft more commonly used in the kamikaze flights was the infamous Mitsubishi Zero — also used for the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in December 1941. However, as the war progressed and the Japanese military became more desperate, the nation unleashed the Ohka (which means cherry blossom). The Ohka was a petite wood-and-metal airplane specifically designed for kamikaze missions. Armed with a ton of explosives in its nose, the Ohka was carried under the belly of a larger twin-engine Japanese bomber. During a mission, the Ohka pilot would ride in the bomber until the target was within 25 to 50 miles. He would then climb down through the bomb bay and into the small Ohka, pull a release lever and be on his way.

Though the little aircraft was primitive, it had a compass, an altimeter, and a toggle switch for firing the primitive propulsion rockets in its tail. By the time the Ohka rammed into an American ship, it would have attained a speed of some 600 m.p.h. — faster even than the average speed of today’s jetliners. Just before impact the pilot would pull a handle to arm the fuse of the nose explosives.

Prior to kamikaze missions, Japanese pilots vowed to take a battleship for every aircraft. And when they did score direct hits, the damage was often immense, with hundreds of American sailors killed and countless more horribly burned. But in fact, personnel on the U.S. ships were able to blast many of the kamikazes out of the sky with antiaircraft fire before the pilots reached their targets.

No historian has ever determined exactly how many Japanese airman perished in suicide attacks and under what circumstances. Eventually, every pilot in Japan’s military was taught how to ram-attacking bombers, and many pilots died in individual, spontaneous attacks that were unrecorded. But it is believed that more than a thousand kamikazes died in suicide attacks, and that more than a third of them were mere teenagers. In tribute, Chiran’s main streets are lined with more than a thousand stone lanterns representing each pilot.

Japanese young people who visit the museum today find the experience a thought-provoking one. Satsuki Watanabe of Kagoshima City says she visits the museum whenever she is in the area. “I have heard that most of the pilots didn’t think the war was necessary, but they felt compelled to defend their country,” she says. “In history, I read that a lot of Japanese people thought that the war was a bad thing, but they had to do it.”

There’s no question that the suicide missions aroused complex feelings in the young kamikazes. Some of the museum’s artifacts hint at the pilots’ torment. Letters bidding farewell to mothers, fathers, and sweethearts convey the writers’ great sadness at having to die so young, as well as their devotion to both family and homeland. Some of the letters, written by the pilots on their final night on earth, can be read in English via touch screens. Just outside the museum, in a small shady cedar forest is a (restored) army pilots’ house where the kamikazes would stay until being sent out on their final missions. Here the young flyers would write short messages or pen farewell notes and letters to be their parents or loved ones. While most foreign visitors to the museum are well aware of the countless atrocities carried out by the Japanese in China and across East Asia, it is not difficult to see that these young flyers were also pawns controlled by Japan’s hard-core military regime.

Before the first Ohka mission, staged in March 1945, the pilots took hair clippings and put them in boxes so that their parents would have something for funeral services. Each then wrote out a statement. One kamikaze pilot’s read: “May our death be as sudden as the shattering of crystal.”

On that first Ohka mission, 18 Japanese “Betty” bombers carrying 15 Ohkas took off from Kanoya Air Base; they were protected by a flight of 30 Japanese fighter planes. But before the Ohkas could be released, 50 American fighter planes attacked the suicide squadron. At the end of the engagement, 160 Japanese — including all 15 of the mission’s Thunder Gods — were dead.

At the entrance of the Chiran Peace Museum, the purpose of the facility is stated as “to commemorate the pilots and expose the tragic loss of their lives so that we may understand the need for everlasting peace and ensure such incidents are never repeated. That is now our responsibility.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com