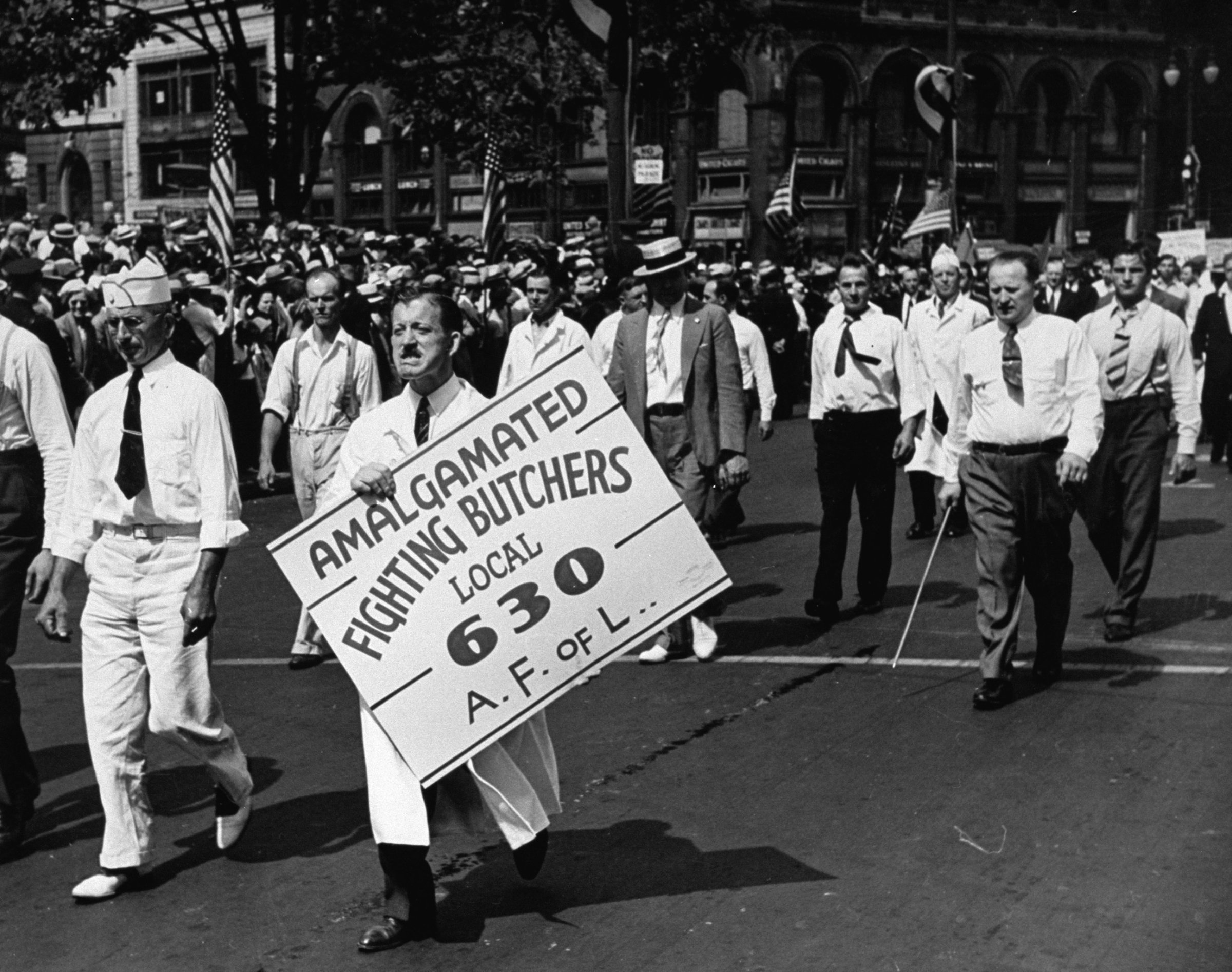

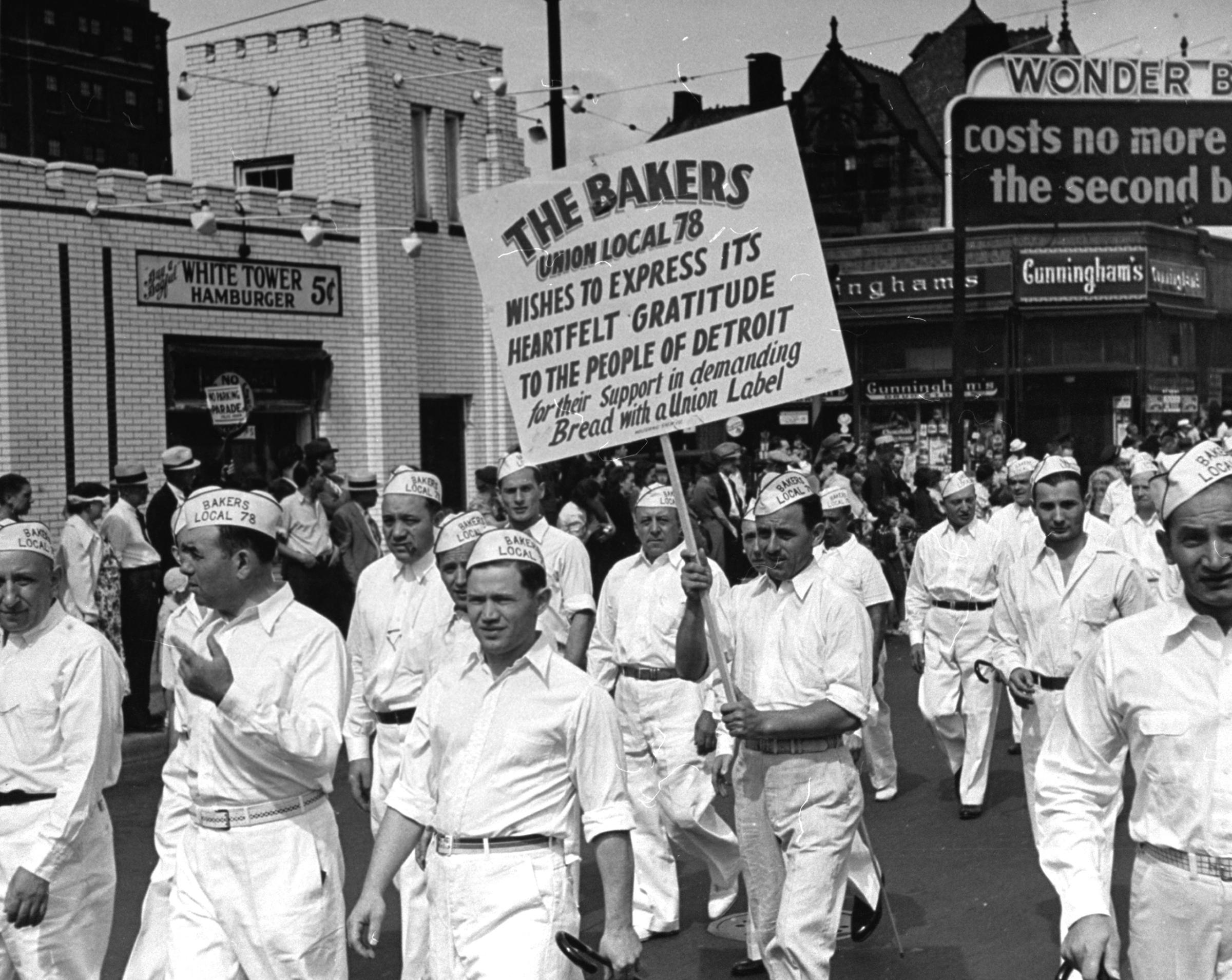

Like many national holidays, Labor Day has taken on many connotations—the unofficial end of summer, the last acceptable day of the year to wear white pants—that are far from its original meaning. When the first nationally recognized Labor Day was celebrated in 1894, the day consisted of a street parade sending up a message of “the strength and esprit de corps of the trade and labor organizations,” in the words of the official magazine of the American Federation of Labor, followed by a festival for workers and their families.

The decision to send LIFE photographer William Vandivert to Detroit for Labor Day in 1938 can only have been an obvious one. The automobile industry was full steam ahead, the city’s population soaring thanks to an influx of ready workers. The United Auto Workers was formed there in 1935. In the early months of 1937, a sit-down strike at the General Motors factory in nearby Flint won recognition of that union as a bargaining agent for autoworkers there, inspiring many similar strikes across the country.

Vandivert’s images capture the dignity of the workers, waving UAW flags alongside the American flag, their union pride elevated to the level of patriotism. He photographed not only autoworkers, but also bakers and butchers, and women and children offering support from the sidelines. The spirit of the day is unmistakable: brotherhood with one’s local chapter members, solidarity with any man—if any women’s unions were in Detroit that day, Vandivert’s lens didn’t find them—who called himself a worker.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizabethronk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com