Harvard Professor Lawrence Lessig knows that running for President would be a bold move.

Some might say it would be quixotic, given Lessig’s plan to resign his presidency if he won after he enacted a single bill aimed at reforming money and equality in elections.

But Lessig says such an audacious claim is necessary because people don’t believe chipping away at campaign finance reform in smaller ways—electing sympathetic congressmen, mobilizing grassroots efforts—will solve the problem. “I thought it was important to have a strategy that is big enough and different enough that people can imagine, they can see how this in fact would do something,” he told TIME. “And if they did see that it would do something, they’d have a reason to step up and support it that they otherwise wouldn’t have for the other smaller kinds of changes.”

Lessig’s one mission as President would be to pass what he calls the Citizen Equality Act. The bill has three main objectives: equal right to vote (through automatic registration and moving voting to a national holiday, among other means), equal representation (by ending political gerrymandering), and citizen funded elections (by giving every voter a voucher to contribute to a campaign).

“The system, by outsourcing funding of campaigns to the tiniest fraction of America, is vulnerable to the instability of that concentration,” Lessig said. “So that is a corruption of the basic equality of a representative democracy, and it makes it so our government can’t do anything.”

Although Lessig, 54, would run as a Democrat, he clerked for conservative Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia at the beginning of his career. He has been a law professor since the early 1990s, working at the University of Chicago Law School, Stanford Law School and Harvard Law School. His initial political activism focused on intellectual property law; fascinated by changing intellectual property disputes in the digital age, he became a founding board member of Creative Commons, an organization founded in 2001 which works to improve copyright practices. In 2007, Lessig announced that money in politics would be his new pet issue, and he hasn’t looked back since.

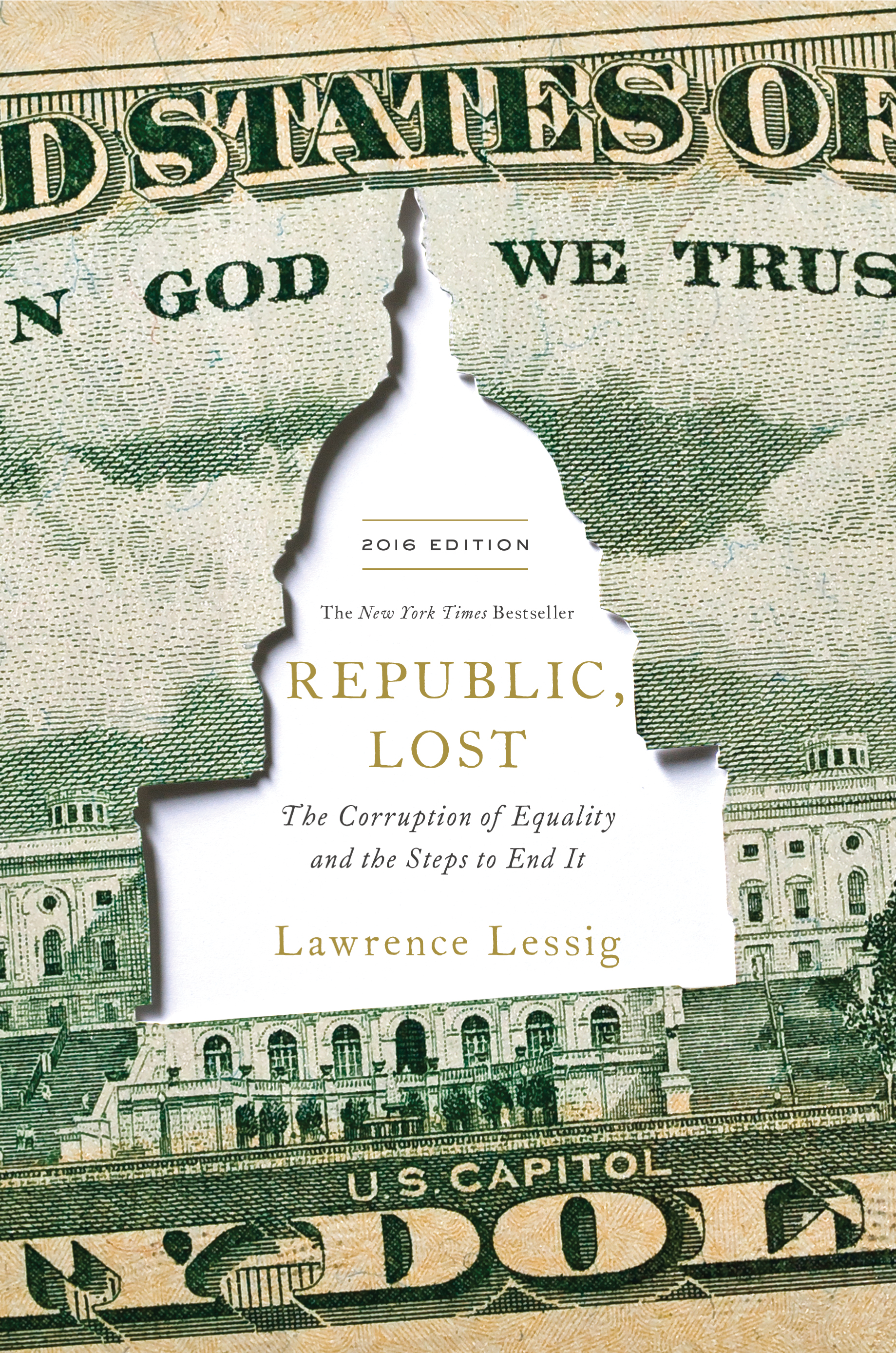

Lessig’s philosophy is outlined in a newly revised edition of his 2011 book, Republic Lost: How Money Corrupts Congress And a Plan to Stop It, to be released October 20 by Hachette Book Group. Until then, he’s testing the waters for a run by crowdsourcing on his website. He says if he can reach $1 million by Labor Day, he’ll jump in the race to be the Democratic nominee. With 14 days left his website shows he’s over halfway there, with $563,310.

But Lessig has worked on reforming the system before, without much success. In 2014, he created a Super PAC called Mayday PAC that aimed to elect a pro-campaign finance reform majority to Congress. The PAC spent more than $10 million on eight races; his chosen candidates won in two races and lost in the rest, with little evidence that his group made much of an impact in any of the contests.

Still, Lessig thinks he would be a better candidate than either Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders or Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the current Democratic frontrunners. “By not prioritizing it and by just mixing it in with everything else, he doesn’t make it credible he can achieve it, and he undermines the credibility of the stuff he otherwise is talking about,” Lessig says of Sanders. And of Clinton: “We’ve got to do more than what she’s talking about.”

Lessig would, however, be open to Sanders as his Vice President. He’s crowdsourcing who his veep should be in a poll on his website (which includes Jon Stewart), but he says he’s “not beholden” to the results of the poll. “The ordinary presidential nominee has freedom to pick [the Vice President] because the hope is the Vice President will never be President, ” he said. “But my Vice President I hope is president as soon as possible.”

The one candidate Lessig thinks makes sense on campaign finance is Republican firebrand Donald Trump. “He’s absolutely right,” Lessig said. “He’s rich, so he’s not dependent, [and] that would make him better than anybody else because of that lack of dependence.”

Still, Lessig cautioned: “But the idea that the only solution to this corruption is to elect billionaires is crazy. That’s what we fought a revolution about.”

Lessig knows that in order to be competitive, he’ll have to prove that he’s capable of leading outside of just this one issue. “Obviously I need to convince people that I would have the judgment and the knowledge [and the] experience,” he said, “And that’s the test of the campaign. And if I decide to run, then questions that test me on that would be completely appropriate.”

But for now, Lessig still doesn’t know if he’s even running. He is waiting to see whether he’ll reach his fundraising goal by September 7. If he doesn’t, he’ll return the money and come up with a new strategy. “My plan has been for the last eight years to give every ounce of my energy to get us back a democracy,” he said. “I’ll do whatever I can.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Tessa Berenson Rogers at tessa.Rogers@time.com