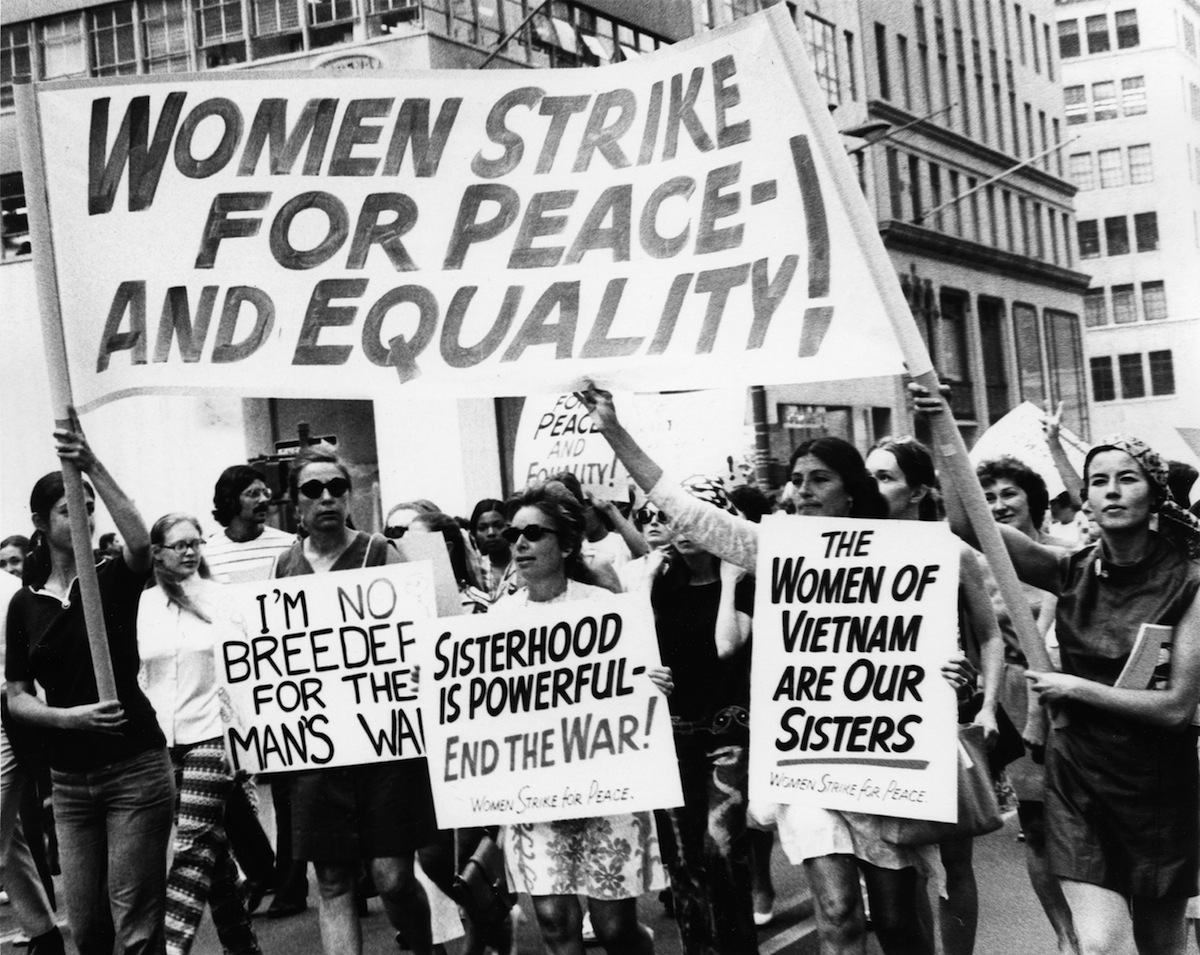

On Aug. 26, 1970, a full 50 years after the passage of the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote, 50,000 feminists paraded down New York City’s Fifth Avenue with linked arms, blocking the major thoroughfare during rush hour. Now, 45 years later, the legacy of that day continues to evolve.

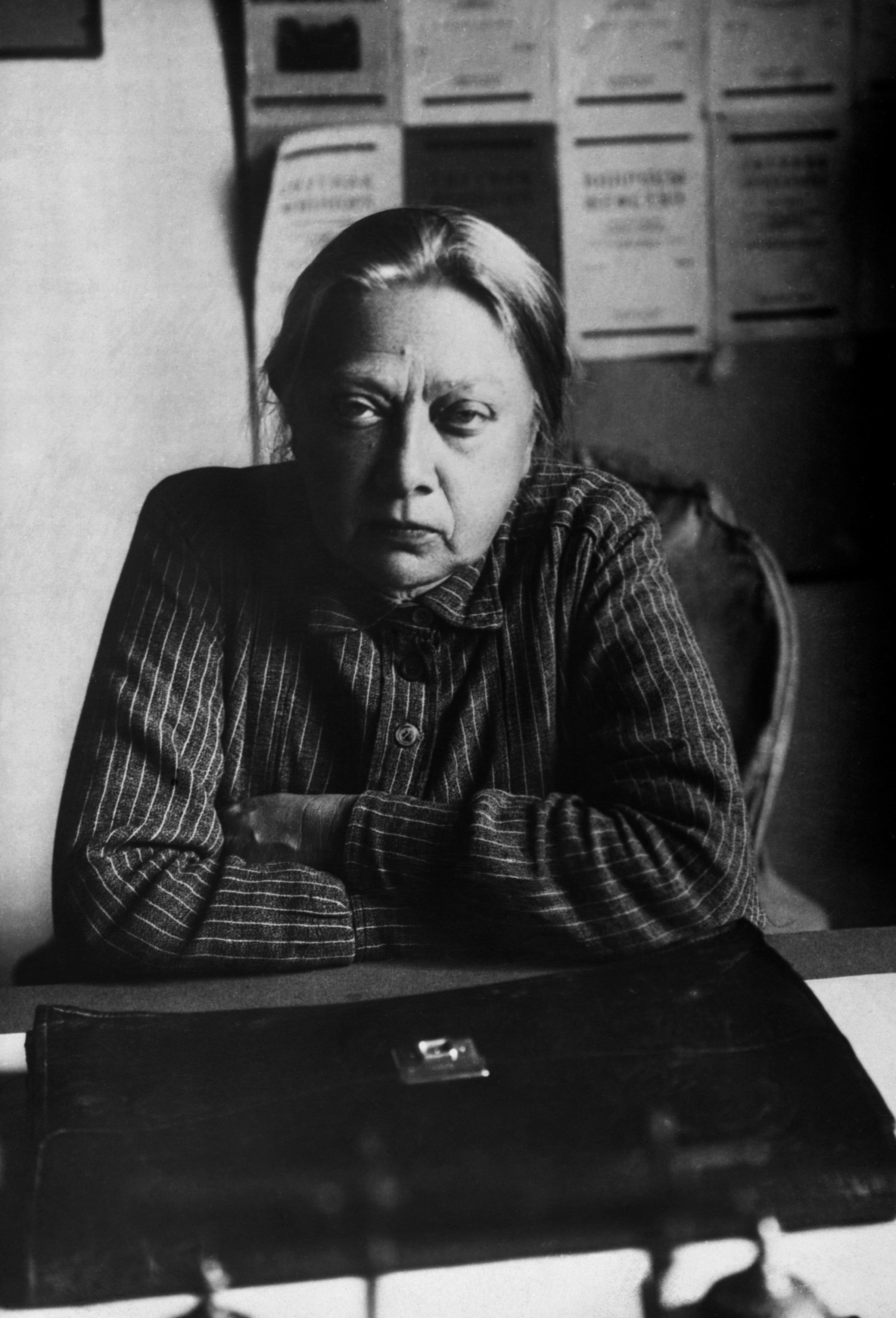

Officially sponsored by the National Organization for Women (NOW), the Women’s Strike for Equality March was the brainchild of Betty Friedan, who wanted an “action” that would show the American media the scope and power of second-wave feminism.

As TIME observed just days before the march, the new feminist movement emerged out of a moment in which “virtually all of the nation’s systems — industry, unions, the professions, the military, the universities, even the organizations of the New Left — [were] quintessentially masculine establishments.” The notion of women’s liberation was extremely controversial, and the movement was in its infancy.

Friedan’s original idea for Aug. 26 was a national work stoppage, in which women would cease cooking and cleaning in order to draw attention to the unequal distribution of domestic labor, an issue she discussed in her 1963 bestseller The Feminine Mystique. It isn’t clear how many women truly went on “strike” that day, but the march served as a powerful symbolic gesture. Participants held signs with slogans like “Don’t Iron While the Strike is Hot” and “Don’t Cook Dinner – Starve a Rat Today.”

The number of marchers exceeded Friedan’s “wildest dreams.” TIME described the event as “easily the largest women’s rights rally since the suffrage protests.” It brought together older, liberal feminists like Friedan and Bella Abzug with a younger, more radical contingent of women. As Joyce Antler, a historian who participated in the demonstration, told me, many of these women “were veterans of civil rights marches and anti-war protests of the 1960s. We marched throughout the ‘60s and we had faith that this mattered.”

The day of activism reached beyond New York City, as thousands of feminists across the country coordinated sister demonstrations. A full range of creative, confrontational tactics was on display, as activists infiltrated “all male” bars and restaurants, held teach-ins and sit-ins, picketed and rallied, in Detroit, Indianapolis, Boston, Berkeley and New Orleans. One thousand women marched on the nation’s capital, holding a banner that read “We Demand Equality.” In Los Angeles, feminists wearing Richard Nixon masks enacted guerrilla street theater. “The solidarity was completely exhilarating,” Antler recalls.

The organizers of the day’s events agreed on a set of three specific goals, which reflected the overall spirit of second-wave feminism: free abortion on demand, equal opportunity in employment and education, and the establishment of 24/7 childcare centers. Over the next several years, activists would use multiple techniques — from public protest to legislative lobbying — in an attempt to turn these goals into realities.

So how did they fare?

The women’s movement was most successful in pushing for gender equality in workplaces and universities. The passage of Title IX in 1972 forbade sex discrimination in any educational program that received federal financial assistance. The amendment had a dramatic affect on leveling the playing field in girl’s athletics. Also, feminists made the workforce a more hospitable space for women with policies banning sexual harassment, something the Equal Opportunity Commission recognized in 1980. Women’s participation in college, graduate school and the professions has steadily increased over the past several decades, although a gender wage gap still exists.

In terms of abortion access, activists have also made great strides since 1970, but have suffered serious setbacks as well. In 1973, after legal strategizing by NOW and other reproductive rights groups, the U.S. Supreme Court legalized abortion in all fifty states. This was a major feminist victory, but it was also limited, as the decision only protected a woman’s right to terminate during her first trimester of pregnancy, allowing for state intervention in the second and third trimesters. Furthermore, Roe v. Wade did not address the cost of an abortion, which was high enough to be out of reach for many women. In the years after the decision, backlash to Roe triggered many varieties of legislation that further eroded women’s access to the procedure.

Perhaps the least amount of progress has been made in the area of childcare, which remains prohibitively expensive for many American women. In 1971, Congress passed the Comprehensive Child Development Act, which would have set up local day care centers for children on a sliding scale based on family income, but Nixon vetoed the bill. While President Obama has spoken about making affordable childcare a national priority, there are no current plans to offer government-funded, round-the-clock care in the United States as feminists had initially envisioned. As of 2014, the average annual cost of enrolling in a daycare center for an infant is, in most states, higher than the cost of a public college in that state.

So the long-term results of the Strike for Equality March have been mixed. But in the short-term, the event did accomplish one major goal: it helped make the feminist movement visible. In the immediate aftermath, a CBS poll showed that four out of five adults were aware of women’s liberation, and NOW’s membership grew by 50%. “The huge number of marchers, young and old, made a convincing case that this was a movement for everyone,” Antler explains. In this sense, the event exemplified cross-generational solidarity among women. Today’s intersectional feminist activists hope to build coalitions across race, class, and sexuality as well, as they work to fulfill the unfinished mission of their foremothers.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Sascha Cohen is a PhD candidate in the history department at Brandeis University, specializing in the social and cultural history of 1970s America.

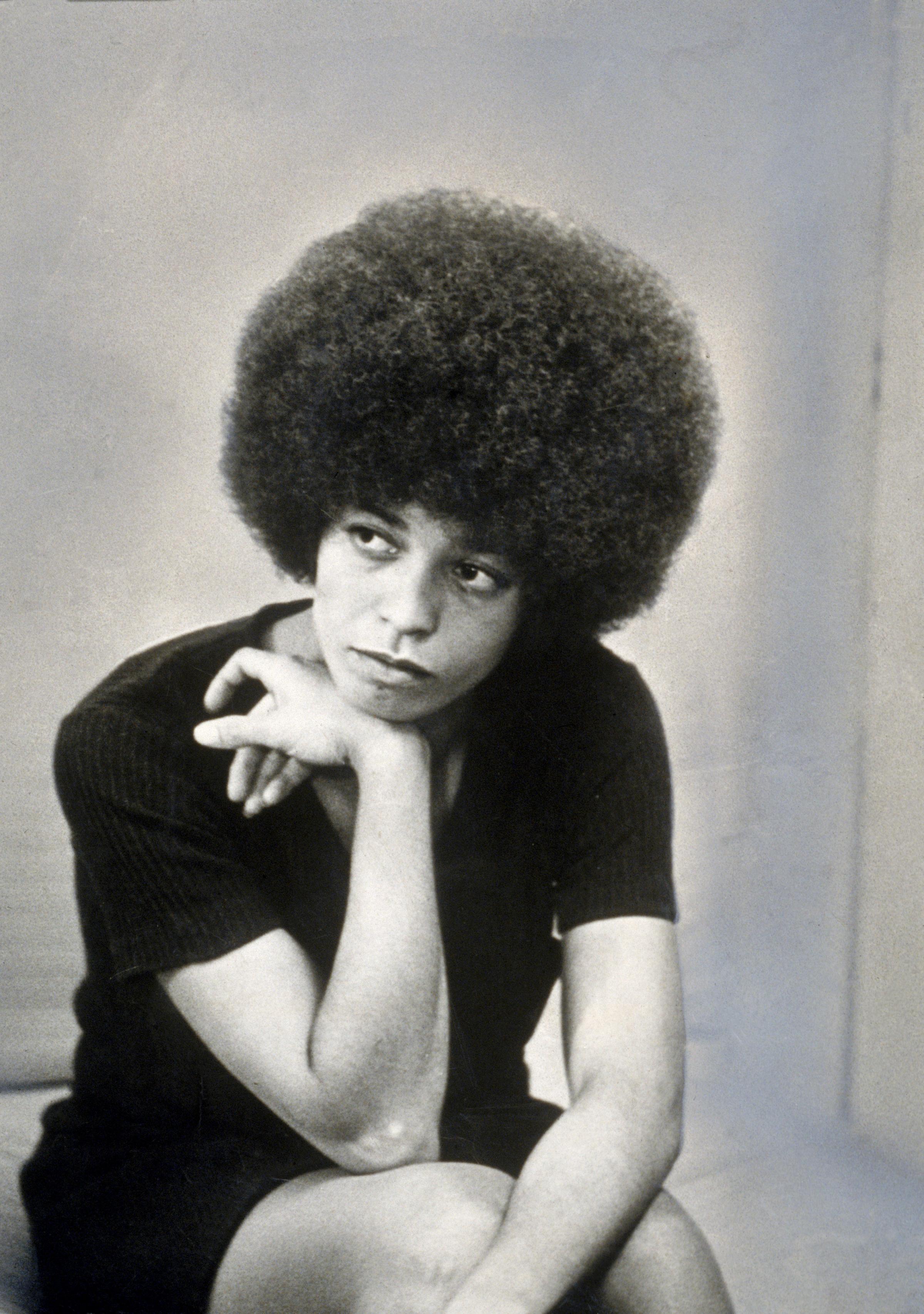

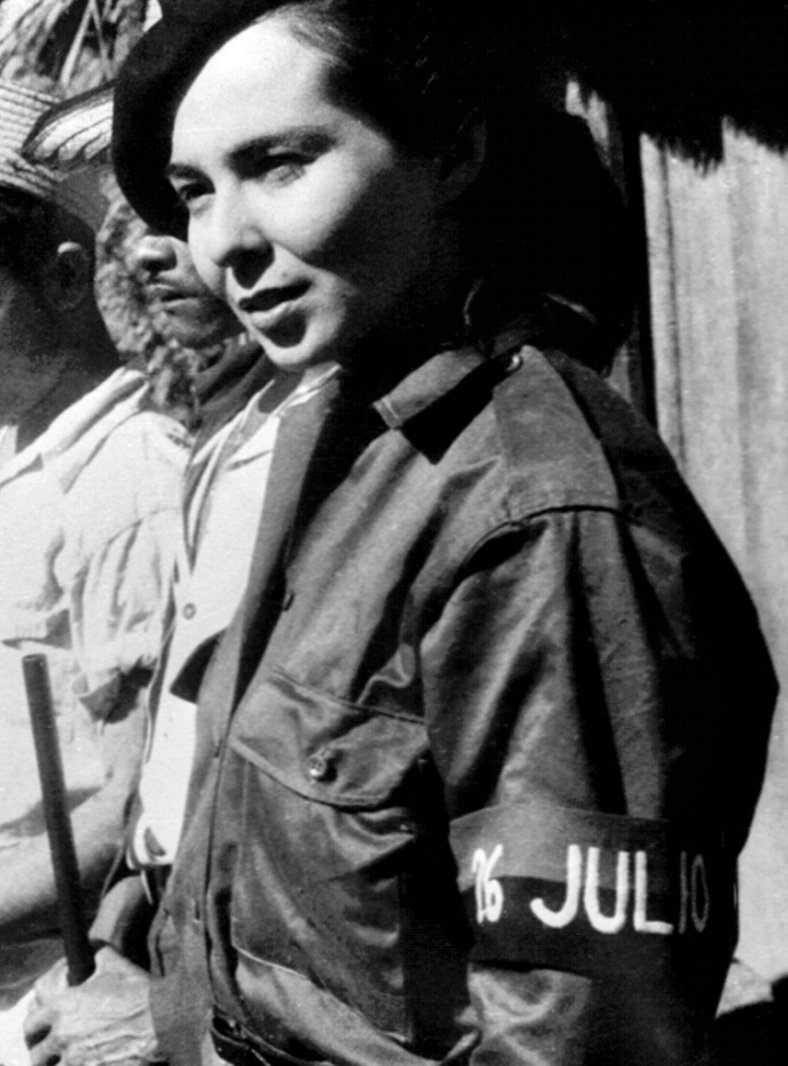

17 of History’s Most Rebellious Women

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com