“What if you gave a war and nobody came?” was the adage uttered amid dwindling public support for the Vietnam War.

This weekend it’ll be replaced with “What if you’re an Army Ranger, but can’t fight?”

That’s because a pair of Army women will graduate Friday from the service’s grueling 62-day Ranger course and earn the prized Ranger tab. That storied black-and-gold patch places them among the nation’s top soldiers (only 3% of their male counterparts have earned it throughout Ranger history). But despite the accomplishment, they’re still barred from direct ground combat, which is the Rangers’ raison d’être.

Earning the tab isn’t a key into the 75th Ranger Regiment, the Army’s top light-infantry outfit, often deployed on the service’s riskiest missions. It simply means they’re eligible for an assignment into that exclusive unit. Pentagon policy currently bans women from serving in direct ground combat slots, which include infantry—like the Rangers—as well as armor, most artillery, and special-operations units.

But the pair’s graduation is a significant crack in the wall keeping women formally off the battlefield. “This is an historic, path-breaking achievement by two exceedingly fit, determined, and professionally competent women who literally `rucked up’ and `walked point’ for their gender,” says one-time Ranger David Petraeus, who went on to wear four stars.

Soldiers who earn the Ranger tab wear it high on their uniforms’ left shoulders for the rest of their careers, though in the past not all male graduates went on to serve as Rangers. Many troops specializing in aviation, intelligence or other career fields will never be able to serve in a Ranger unit, but that tab places them among the Army’s finest warrior-leaders and is seen as a first-class ticket to future promotions.

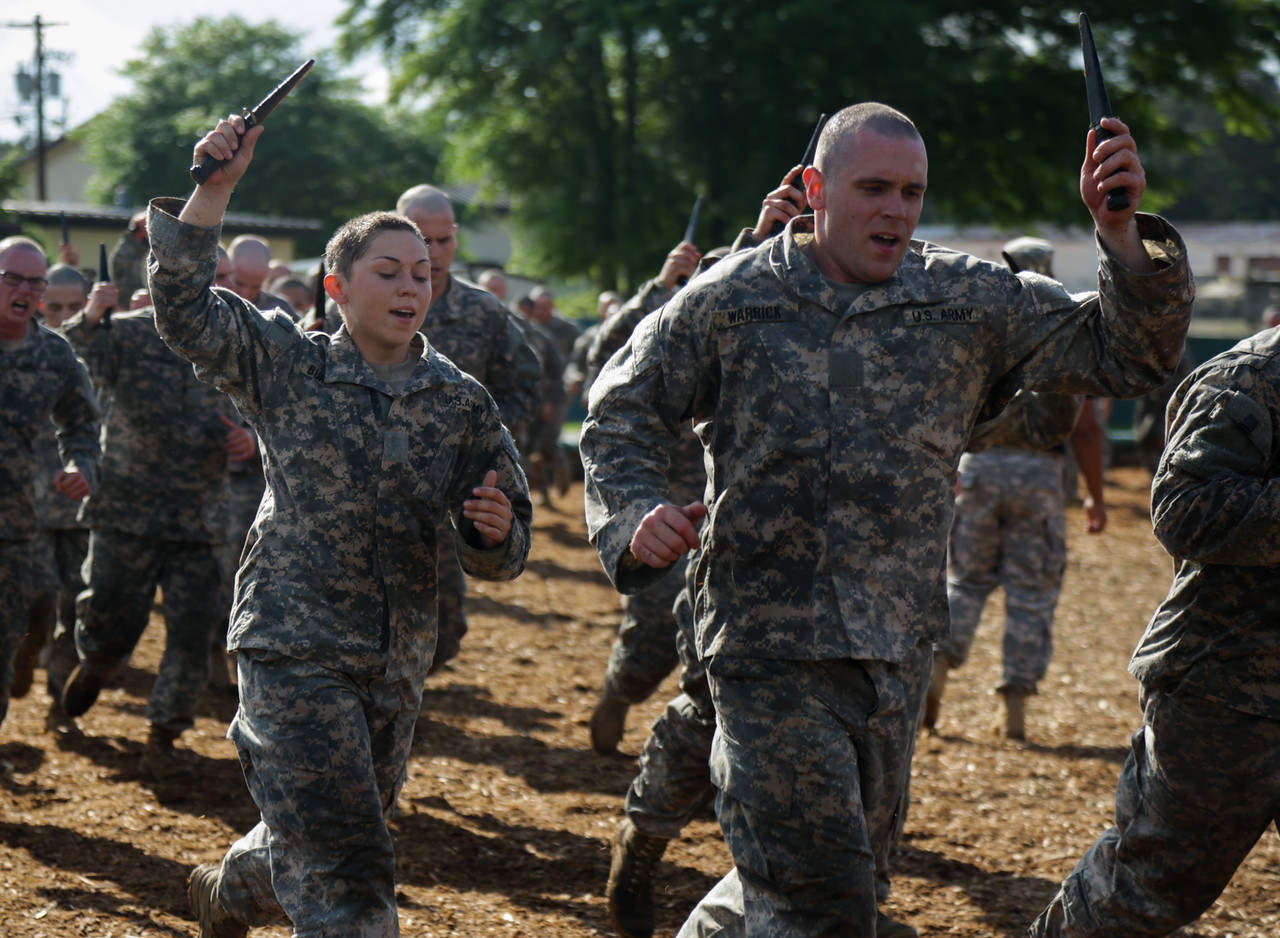

Ranger School is the Army’s top combat leadership course, and teaches Rangers how to overcome fatigue, hunger, and stress to lead troops during small-unit operations, the very heart of warfare. It’s no Boy Scout camp, according to General David Perkins, the Army’s top trainer. “Most people in the Army don’t go to Ranger School. Most of the males don’t want to go to Ranger School,” he said recently. “Most of the males that do go to Ranger School fail.”

The Columbus Ledger-Inquirer, the local paper near the Ranger School at Fort Benning, Ga., identified the women as 1st Lieutenant Kristen Griest, a military police officer from Orange, Conn., and Captain Shaye Haver, an AH-64 Apache helicopter pilot from Copperas Cove, Tex. The two soldiers, both West Point graduates, find themselves in a limbo created by the Pentagon as it grapples with integrating women ever more deeply into the military’s combat units. It’s basically trying to amass a stockpile of Ranger-tabbed women believing the Pentagon will lift that ban early next year.

Responding to a 2013 order from then-defense secretary Leon Panetta that all military jobs should be open to women in 2016, the services have been conducting tests over the past two years to see if women can handle the dirtiest, most demanding ground combat assignments. While the services may, in the coming months, seek to keep some jobs male-only, the final decision will be made by Defense Secretary Ashton Carter in January.

Skeptics of the move to open up combat slots to women say that while there is no doubt some women can serve in front-line units, there won’t be enough to achieve a “critical mass” to make them a true part of combat units. They fear unit cohesion—the glue that binds soldiers together in battle—will weaken amid sexual dynamics in co-ed front-line units. Male troops can be ordered into combat—will women face that same requirement? And will they have to register for the draft?

The pending female Rangers has generated polarized debates across many military-related websites. Proponents say women have been in combat for decades, and that their ability to attend Ranger School simply recognizes the changing combat realities that have blurred the front lines in warfare. The growing role of women in combat, they maintain, isn’t that much different from the racial integration of the ranks that took place after World War II, or the recent change that allows openly gay troops to serve. Critics insist standards have been eased, often on the sly, to let more women serve in combat roles.

The Ranger course, spread over Army posts in Florida and Georgia, includes arduous assignments in woods, mountains and swamps. It includes many physical requirements, including 49 push-ups, 59 sit-ups, a five mile run in 40 minutes, and six chin-ups; a swim test; a land navigation test; a 12-mile foot march in three hours; several obstacle courses; four days of military mountaineering; three parachute jumps; four air assaults on helicopters; multiple rubber boat movements; and 27 days of mock combat patrols.

“This course has proven that every soldier, regardless of gender, can achieve his or her full potential,” Army Secretary John McHugh said. “We owe soldiers the opportunity to serve successfully in any position where they are qualified and capable.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com