Correction appended, Aug. 15, 2015

The primary season that looked so predictable just a few months ago has been disrupted by extraordinary events. The expected battle of the dynasties between Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush no longer seems inevitable. Thanks to a crowded field that includes Donald Trump and the GOP’s early debate kick-off, the Republicans are getting more attention—but equally dramatic shifts are beginning on the Democratic side. In fact, the Democrats may be facing a replay of the election that put an end to their 36 years of political hegemony in the middle of the last century: the election of 1968.

Just as President Lyndon Johnson, whom everyone expected to run for re-election, symbolized the Democratic establishment then, Hillary Clinton does now. While Johnson controlled the party apparatus (which in 1968 still chose most of the delegates), Clinton has locked up most of the Democratic donors. Both of them, too, have already lost a nomination battle to a younger, more attractive candidate: LBJ to JFK in 1960, and Clinton to Barack Obama in 2008. And both have serious vulnerabilities that pundits initially underestimated: the Vietnam War for Johnson, and the ongoing email scandal for Clinton. Both of them seem to struggle to appeal to a huge new generation of voters: Boomers in 1968, Millennials now. And like Johnson, Clinton has been challenged by an insurgent Senator with unusual views. Bernie Sanders of Vermont has cast himself in the role of Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, whom no one gave a snowball’s chance in hell when he announced for President late in 1967. When McCarthy nearly beat Johnson in New Hampshire, the President shocked America by dropping out of the race. Bernie Sanders has just surged ahead of Clinton in New Hampshire in at least one poll, and like McCarthy, will likely command the support of an army of young volunteers there.

This, however, is only the beginning of the parallels between the two years. When Johnson dropped out, Vice President Hubert Humphrey stepped in as the establishment candidate. Our current Vice President, Joe Biden, has so far resisted entreaties from friends and family to enter the race against Clinton, but were she to withdraw, he could very naturally step into the role that Humphrey filled. Their strengths and weaknesses are remarkably similar. They are both warm, hearty traditional liberals with a reputation for talking too freely and sometimes erratically. Biden’s road to the nomination, however, would be much more difficult than Humphrey’s. Humphrey did not enter a single primary, but thanks to the party organization, he arrived at the Chicago convention in August with a solid majority of delegates behind him. Biden would have to win primaries against Sanders—but would Sanders be his only major rival?

There was, of course, another major actor in the race in 1968: Robert Kennedy, who had been elected as a Senator from New York four years earlier. In the fall of 1967 he had resisted the pleas of numerous staffers and supporters when he decided not to enter the race against Johnson. He was still only 42 that year, he had good relations with Democratic bosses in various parts of the country and he did not want to risk his future by tearing the party apart. But when McCarthy nearly beat Johnson in New Hampshire, he “reassessed” his position and entered the race. That split the Democratic Party yet again, between loyal McCarthy supporters who damned RFK as an opportunist, and those who regarded him as a serious candidate and felt the magic of the Kennedy name. On the last day of his life, Kennedy surged ahead of McCarthy by winning the California primary. (I personally have never believed that he could have won the nomination, but a Humphrey-Kennedy ticket would probably have beaten Richard Nixon.) His entry into the race proved that a contest that had once looked like it had only one possible outcome could remain unsettled to the end.

The obvious candidate to fill RFK’s role as the one to shake things up would be another four-year Senator with a national following, who has resisted numerous urgings to get into the race earlier this year: Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts. Warren insists that she is not going to run, but it’s always possible that she might feel very differently about a race against Sanders and Biden, should Clinton’s campaign founder. She is surely more electable than Sanders. She has impeccable credentials as an economic liberal, and she would be fighting to become the first woman in the White House. Sure, it’s a long shot, but—while the Republicans are getting most of the attention now—history proves that the Democrats are still worth watching.

Correction: The original version of this story misstated the year when Barack Obama beat Hillary Clinton for the Democratic presidential nomination. It was 2008.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

David Kaiser, a historian, has taught at Harvard, Carnegie Mellon, Williams College, and the Naval War College. He is the author of seven books, including, most recently, No End Save Victory: How FDR Led the Nation into War. He lives in Watertown, Mass.

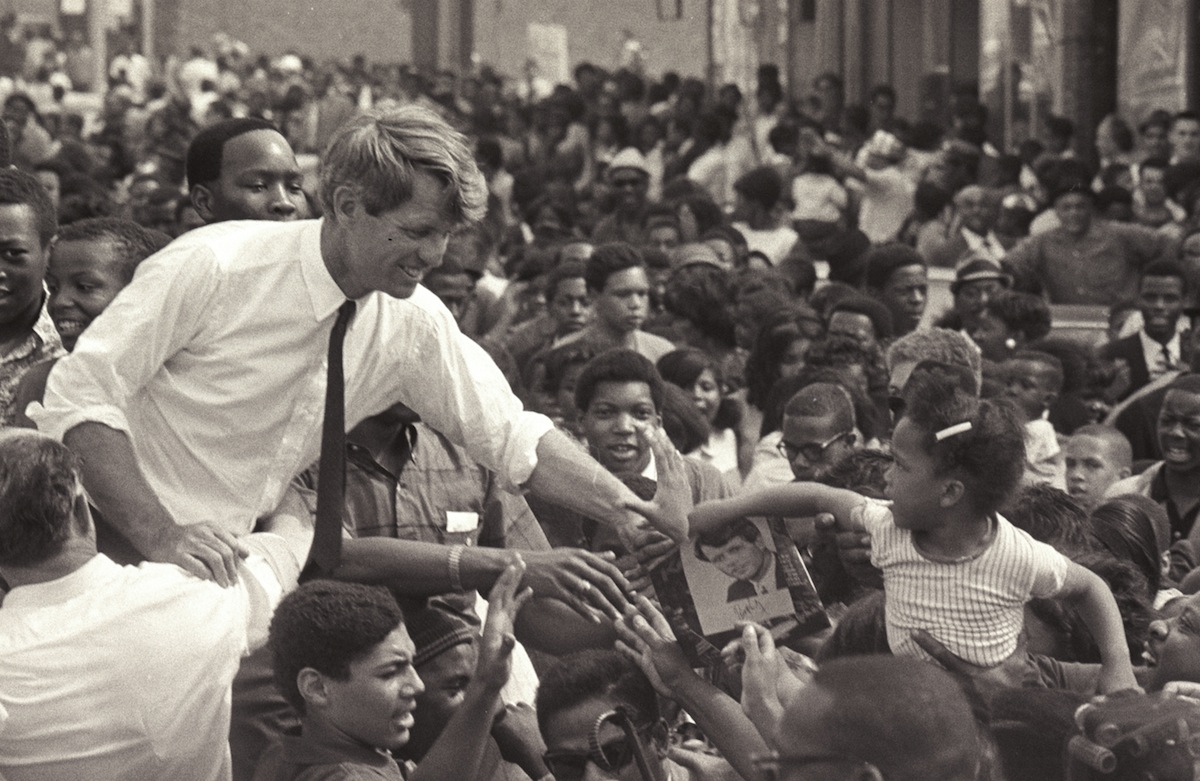

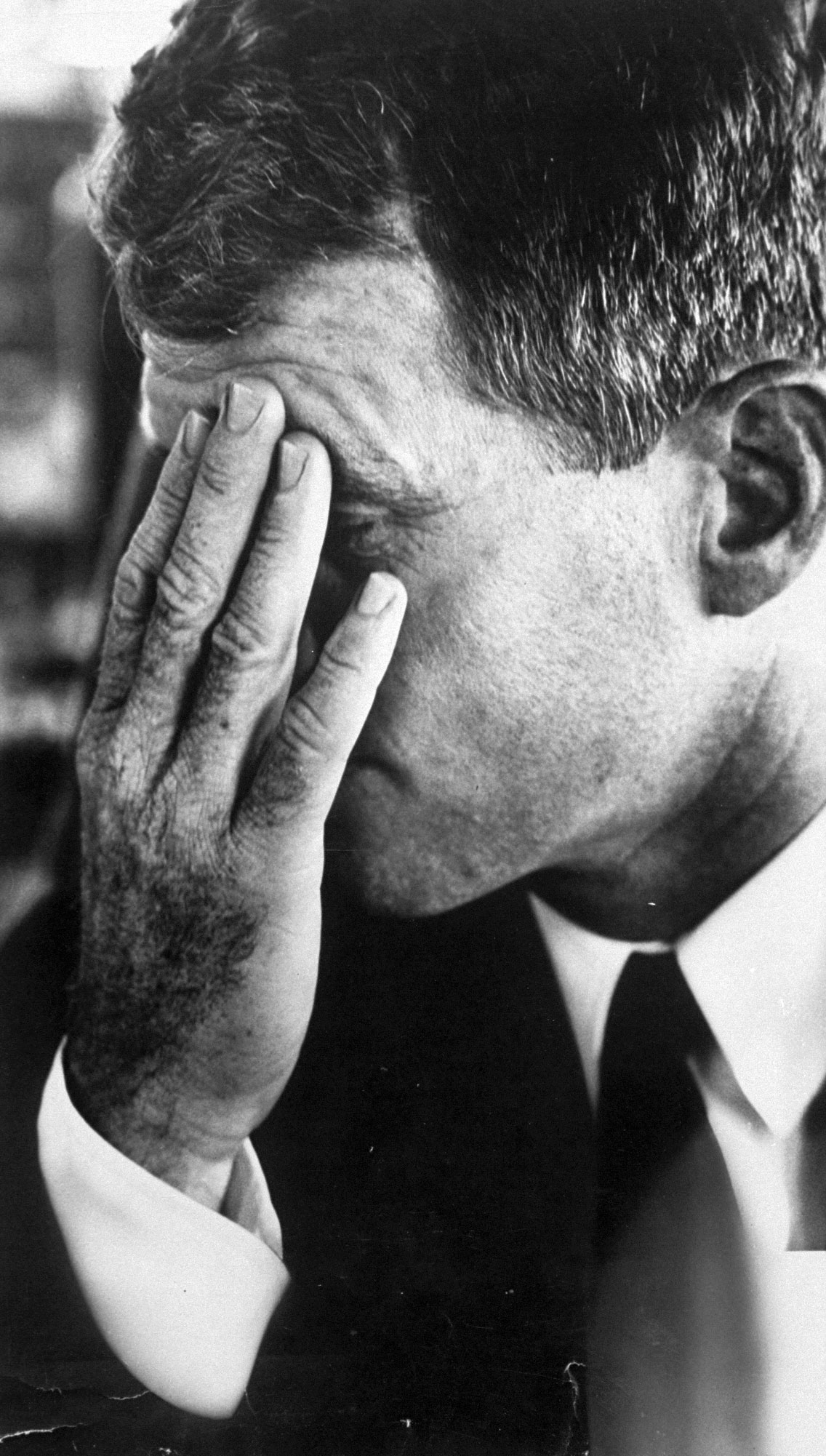

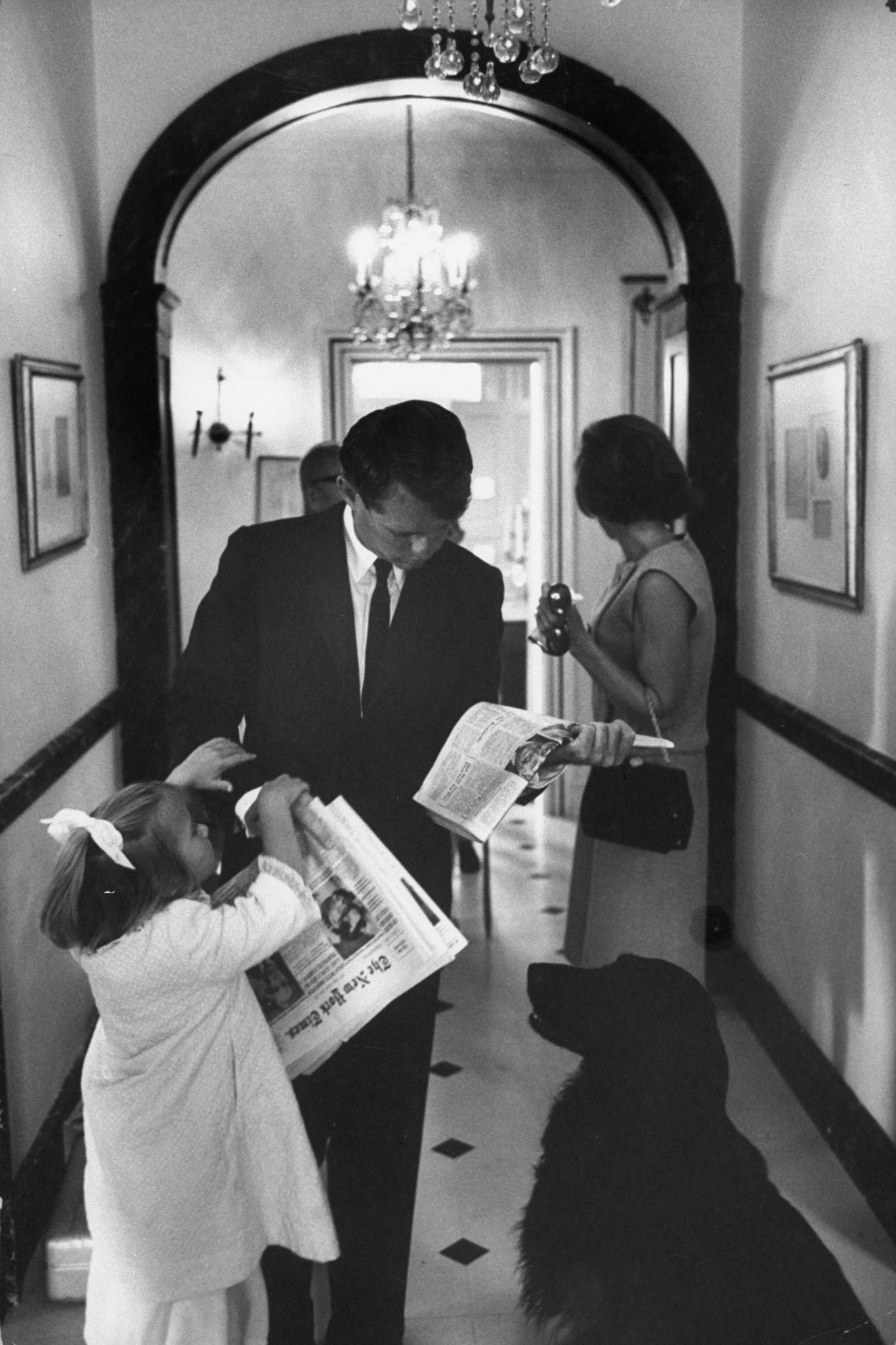

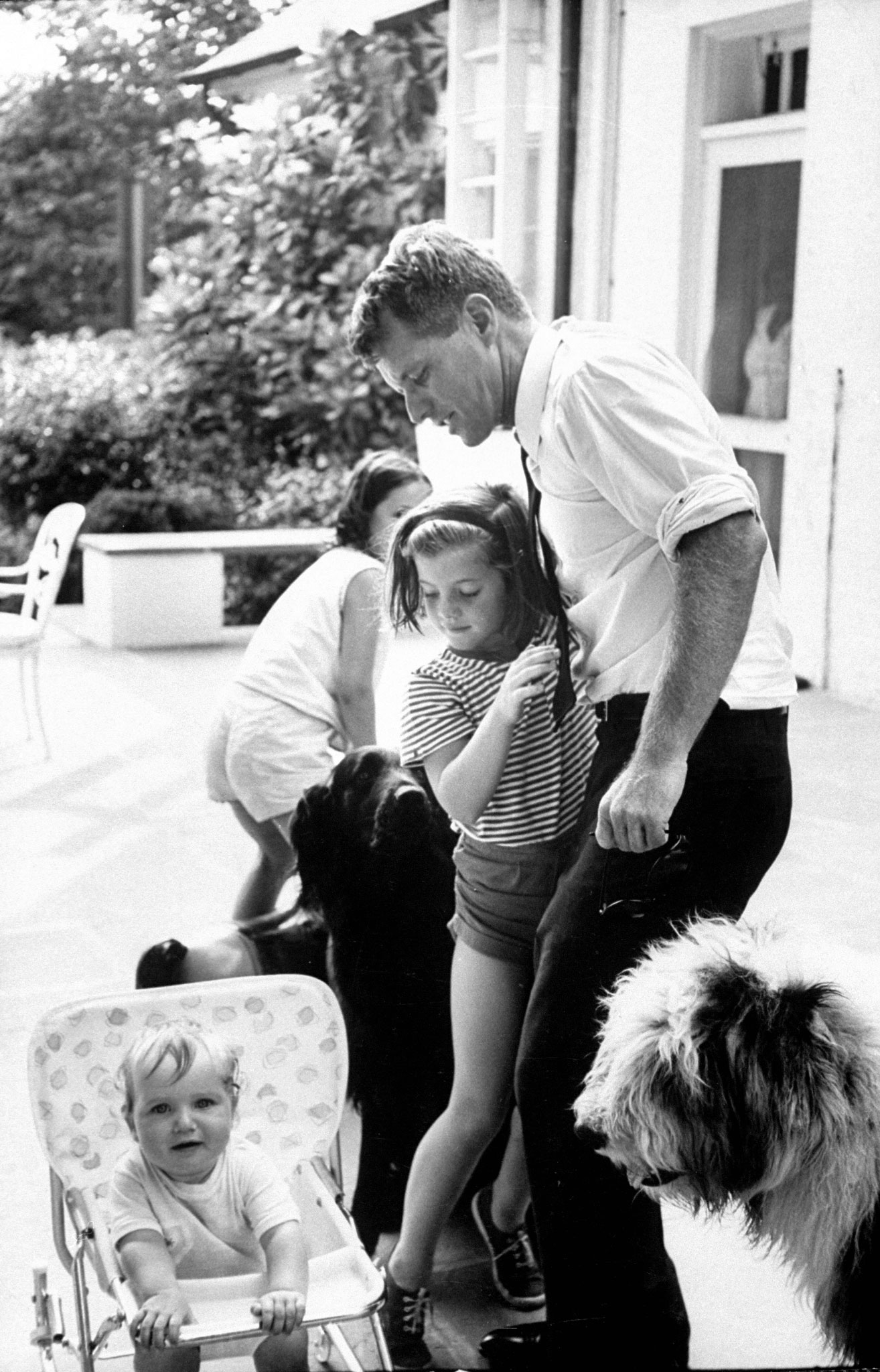

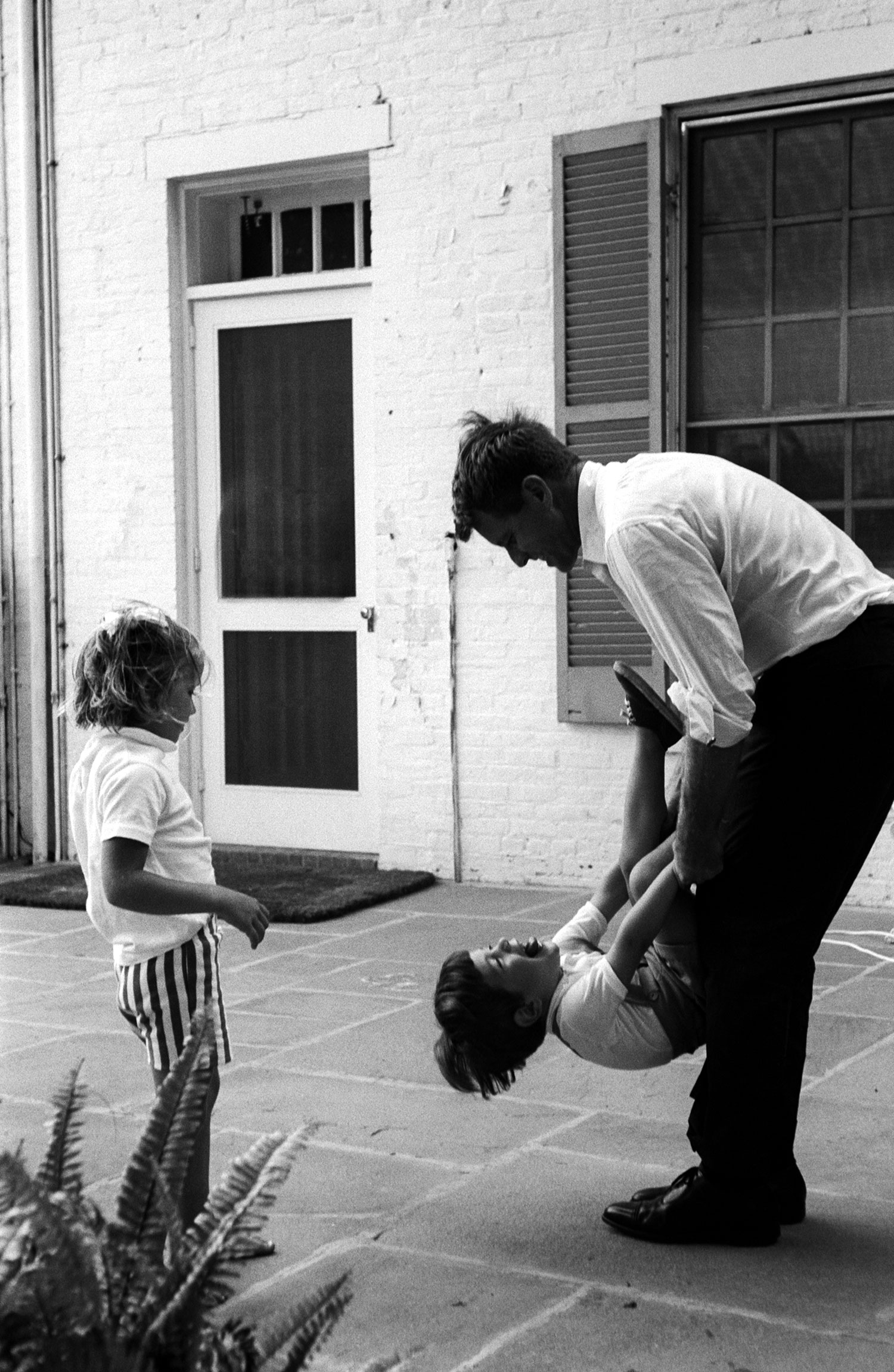

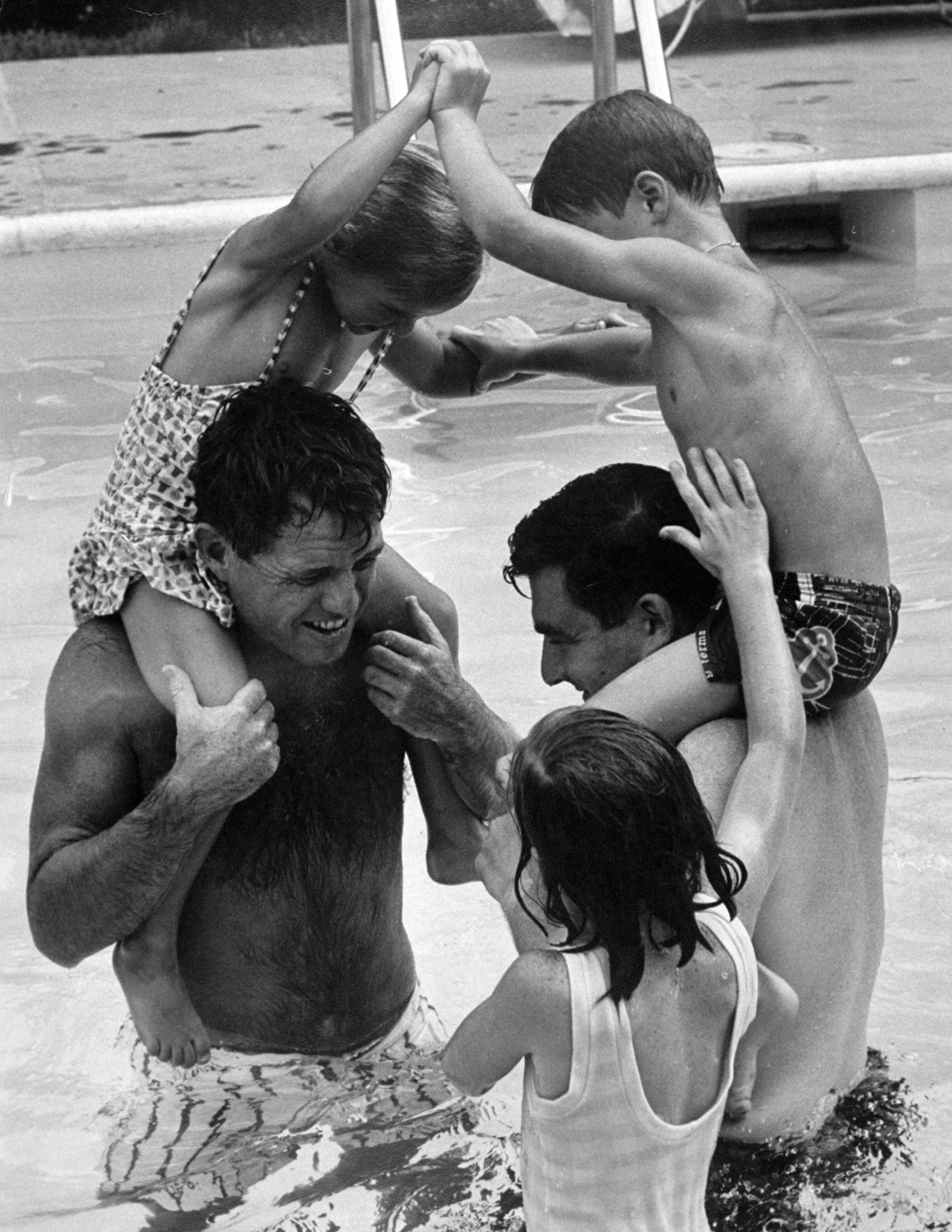

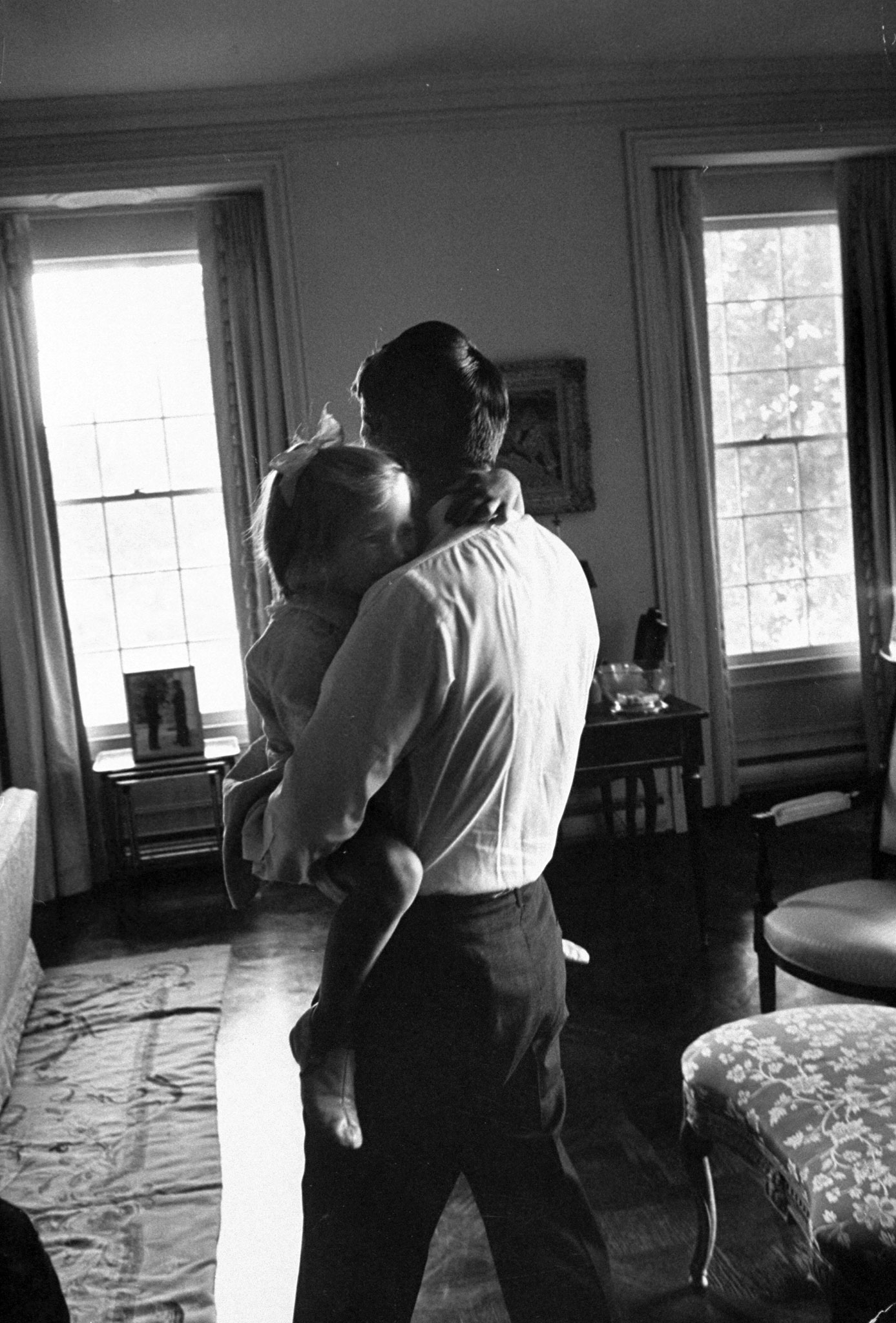

Robert F. Kennedy: Rare and Classic Photos

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com