Hillary Clinton’s campaign stop in Keene, N.H., on Tuesday was billed as a community discussion on substance abuse. But some of the attendees had other matters on their minds.

Five members of the Black Lives Matter movement showed up to buttonhole the Democratic frontrunner about the tough-on-crime policies Clinton promoted during her husband’s presidency. Arriving late, they were barred from entering the packed forum at a local middle school—a decision made by the local fire marshal, according to the Clinton campaign. When the event was over, the former Secretary of State met privately with the activists.

The meeting had mixed results. “She was projecting that what the Black Lives Matter movement needs to do is X,Y and Z,” Julius Jones, a founder of the Black Lives Matter chapter in Worcester, Mass., told the New Republic, which broke the news of the planned disruption. “We pushed back [to say] that it is not her place to tell the Black Lives Matter movement or black people what to do, and that the real work doesn’t lie in the victim-blaming that that implies. And that was a rift in the conversation.”

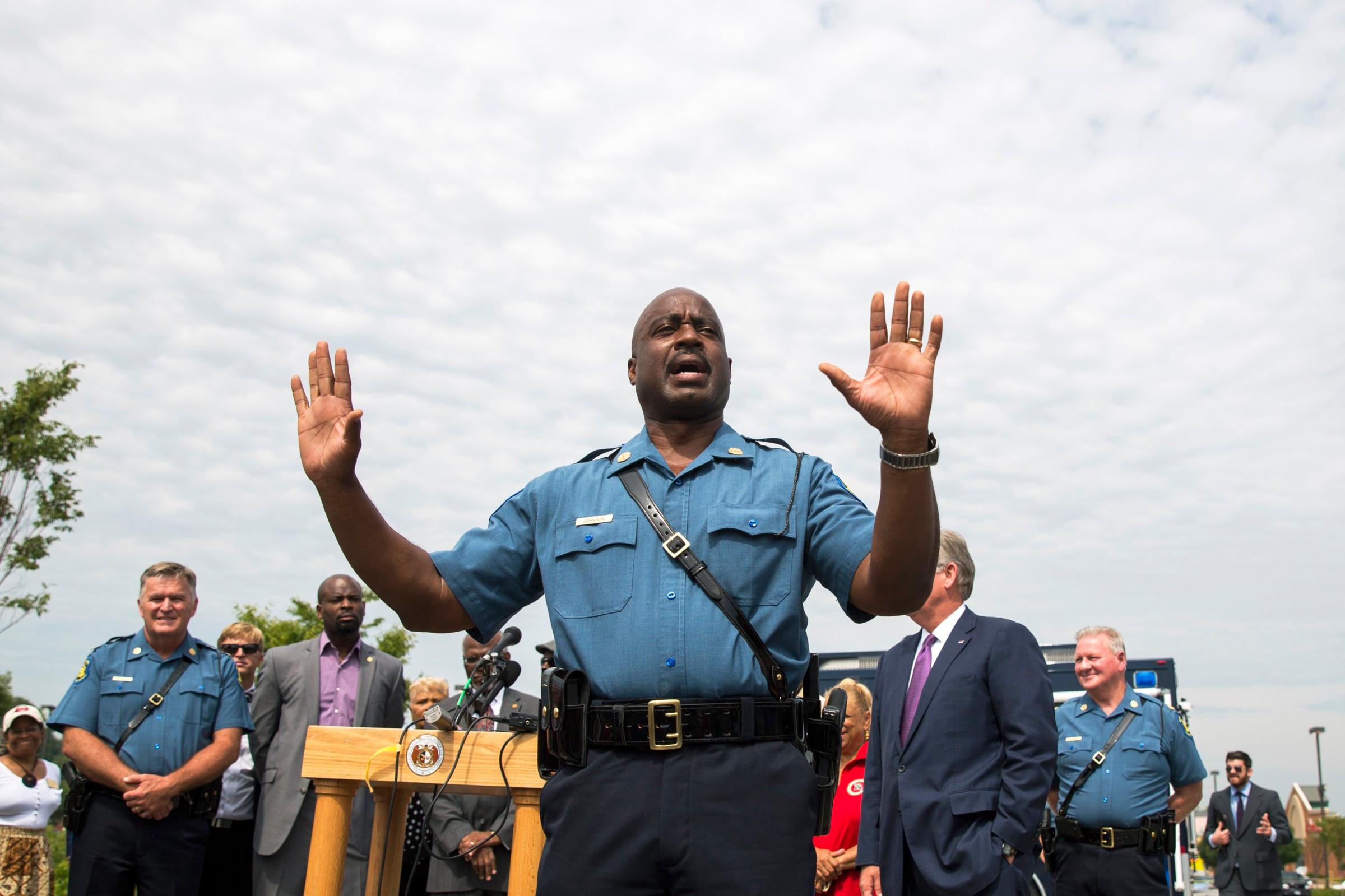

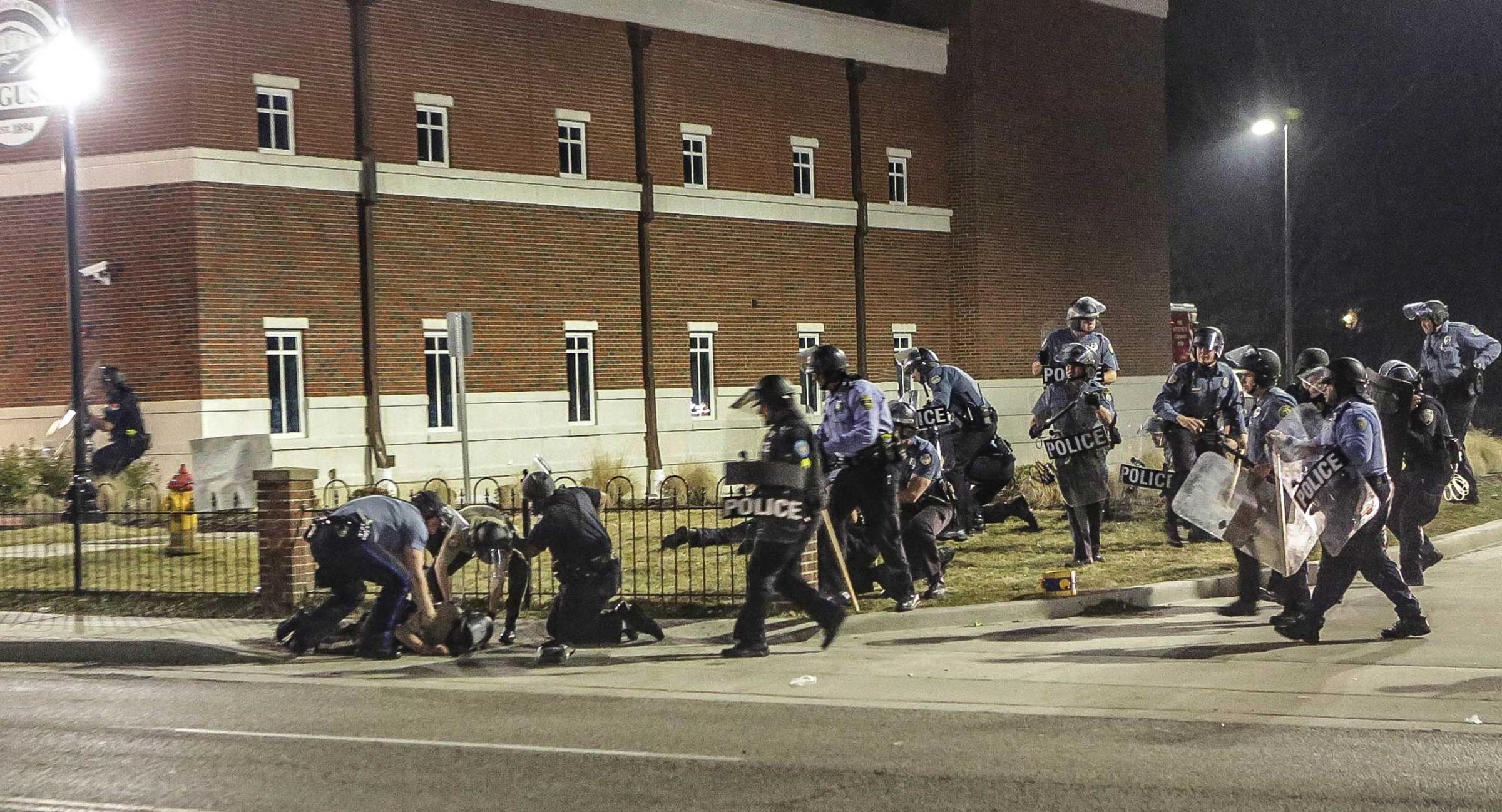

It was also a reflection of the ongoing struggle of Democratic presidential candidates to connect with a protest movement that is only gaining steam a year after Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Mo. Activists have criticized each of the top Democratic candidates for failing to make the flaws of the U.S. justice system a significant part of their campaigns. At times, the friction has spilled into public view.

Members of Black Lives Matter have twice interrupted public events held by Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, whose peevish reaction to the disruptions stoked tensions further. Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley drew jeers when he responded to protesters at Netroots Nation in July by proclaiming that “all lives matter,” which activists think undercuts their message. Clinton angered activists in June by using the same phrase at a Missouri church near Ferguson, where protests to commemorate Brown’s death sparked another spasm of violence in recent days.

The uneasy relationship between the potential Democratic standard-bearers and a pillar of the party’s electoral coalition carries significant consequences. A linchpin of the Democratic blueprint for holding the White House is repeating the success Barack Obama enjoyed with black voters. In 2012, Obama was lifted to victory by the historic black turnout, which surpassed the percentage of white voters for the first time since the Census Bureau began tracking such figures in 1996. But without Obama at the top of the ticket in recent mid-term elections, Democrats have failed to muster the same enthusiasm among blacks. Democratic strategists acknowledge a dip in the community’s voting rate in 2016 would dent the party’s chances.

Members of the Black Lives Matter movement say that is a distinct possibility, depending on whether the Democratic nominee can repair a frayed relationship. “We are going to have very clear demands,” says Brittany Packnett, an educator and activist. “If those aren’t met, you may see people behaving in alternative ways. People may not show up to vote.”

In the activists’ eyes, each of the candidates must overcome checkered records on criminal justice. The 1994 crime bill signed by Clinton’s husband consigned a generation of blacks to lengthy prison sentences for nonviolent crimes. As mayor of Baltimore and later as governor, O’Malley took a zero-tolerance approach to community policing, sparking tensions that exploded into rioting last spring when 25-year-old Freddie Gray died of injuries sustained in police custody. Sanders touts his record of civil-rights activism, but as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, he voted for the 1994 crime bill. Now a senator from an overwhelmingly white state, his campaign has largely focused on economic rather than racial inequality.

“There’s something insufficient about all of them,” says one activist associated with Black Lives Matter.

The candidates are taking steps to convince the movement they are allies, not adversaries. Senior officials with each of the campaigns have initiated discussions with prominent figures in the movement, such as Packnett, who was tapped by the Obama Administration to serve on a White House task force studying police reform, and DeRay McKesson, one of its most visible figures. Clinton delivered a speech on justice reform that acknowledged and denounced “the inequities that persist in our justice system.” Sanders hired a well-respected black organizer and unveiled a new criminal justice-plan this week.

O’Malley has done perhaps the most to make criminal justice a centerpiece of his platform. He has called for a constitutional amendment to protect each citizen’s voting rights. And he recently released a detailed criminal-justice platform that calls for body cameras, national use-of-force standards, better data collection on police shootings and an end to mandatory minimums for drug crimes, among other reforms. Democrats, he explained in an interview with Ebony, can’t expect to marshal “a large and diverse coalition if we’re not able to speak to the concerns of everyone within that coalition.” But O’Malley must square that rhetoric with a record of tough-on-crime policies. When he cut short a European trip to return to his scarred hometown during the riots, some Baltimore residents reacted with boos.

“All three candidates have responded to the movement in some way,” Mckesson says. “Their rhetoric has caught up.” But activists are still waiting to see how talk translates into policy.

See 23 Key Moments From Ferguson

Read next: This Photographer Shows What It Means to Be a Cop Today

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Alex Altman at alex_altman@timemagazine.com