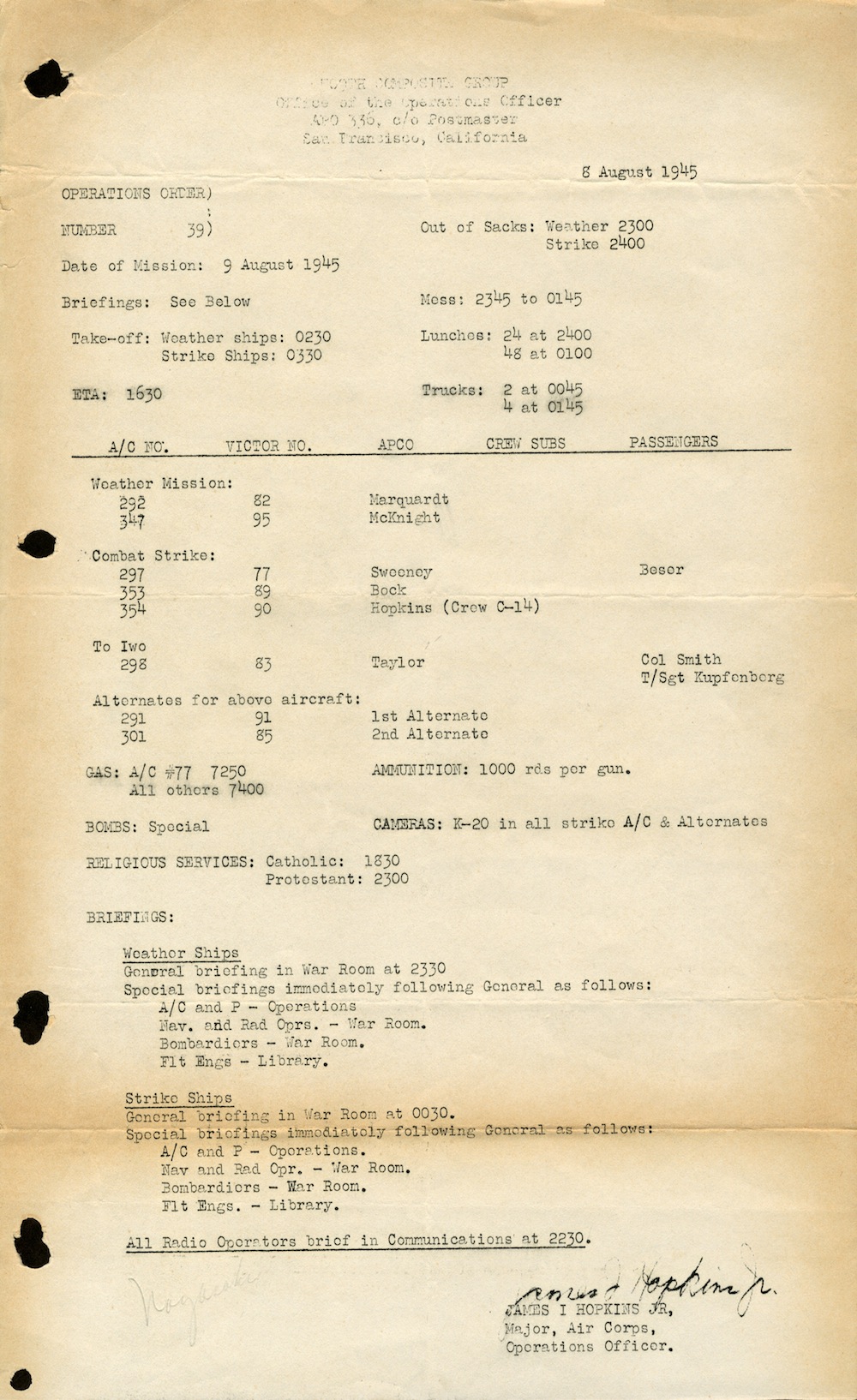

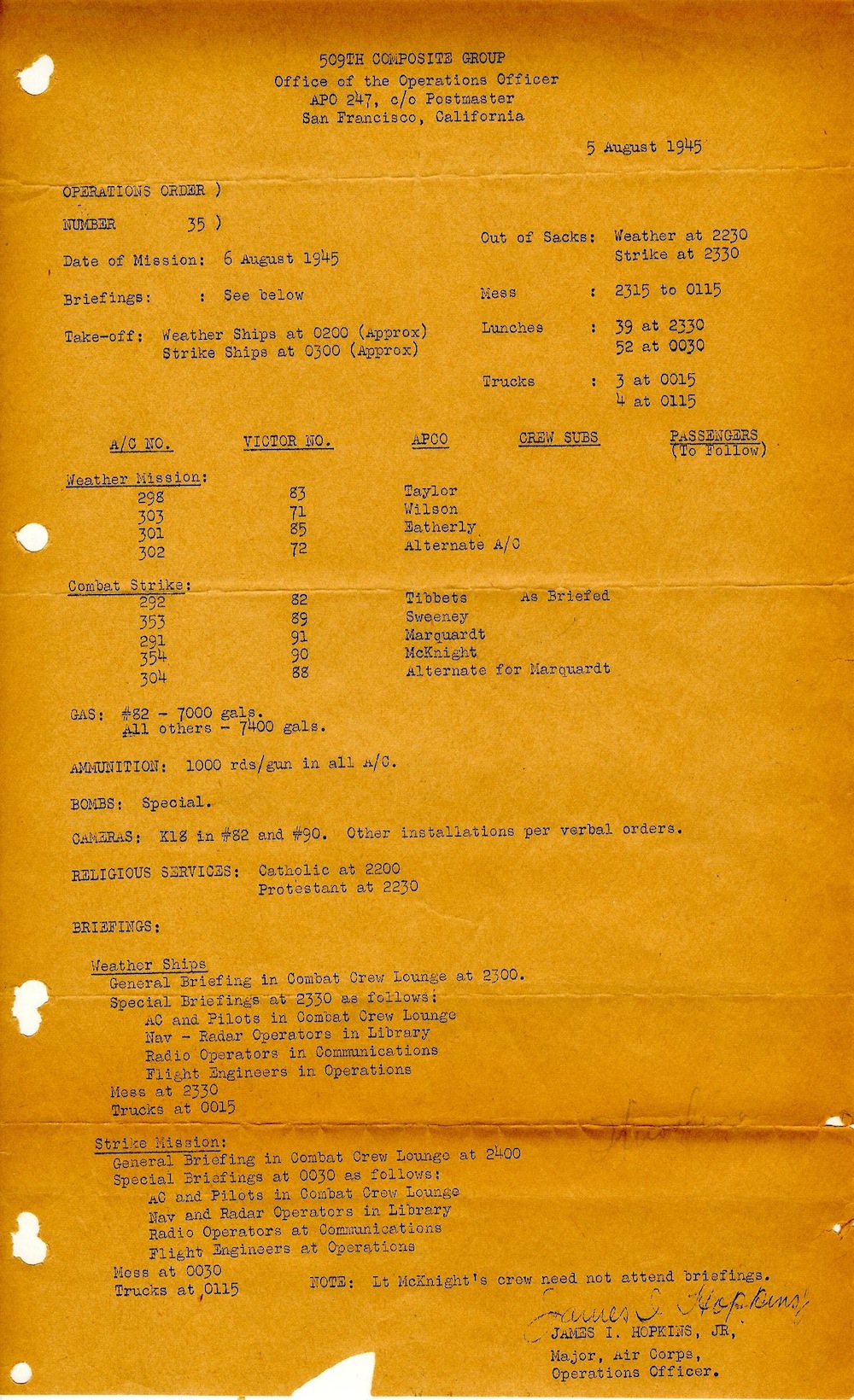

The piece of paper seen above (hover over to zoom; on mobile, click to zoom) was given to Jacob Beser on Aug. 8, 1945. The next day, the electronics specialist boarded a plane bound for Nagasaki. His job was to make sure no radio waves interfered with the mechanisms of the flight’s most important passenger: an atomic bomb. Just days before, Beser had fulfilled the same mission on board the Enola Gay on its trip to Hiroshima; the operations order for that flight is below.

Many years later, Beser—the only man to fly both atomic-bomb missions—met Kenneth Rendell, the founder and director of the Museum of World War II in Natick, Mass., whose collection includes Beser’s operations orders. Both bear the faint, handwritten notes where Beser marked which document belonged to which city.

“[These documents] are a real window into what went on,” Rendell tells TIME. The mentions of prayer, of weather ships going out early to see how the cloud cover was, of what time participants had to wake up (“out of sacks”)—these details bring a human touch to a series of events that forever changed the world. “You get a sense of a snapshot of what was happening with these people,” he says.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com