A little before midnight on Saturday, a crowd of around 700 gathered in an old industrial warehouse a few blocks from the Detroit River for what they’d been told was the “largest public satanic ceremony in history.” Most of them professed to be adherents of Satanism, that loosely organized squad of the occult that defines itself as a religious group. Others came simply because they were curious. After all, Satanists exist in the popular psyche as those who casually sacrifice goats and impregnate Mia Farrow with Lucifer’s child; if this ceremony was indeed unprecedentedly big, who knew what could be in store?

Read more: The Evolution of Modern Satanism in the United States

The reality of the event — and of the contemporary Satanic movement at large — was tamer, and, if the Facebook pictures speak the truth, harmlessly festive: a cross between an underground rave and a meticulously planned Halloween party. They were there to publicly unveil a colossal bronze statue of Baphomet, the goat-headed wraith who, after centuries of various appropriations, is now the totem of contemporary Satanism. The pentagram, that familiar logo of both orthodox Satanists and disaffected teens, originated as a rough outline of Baphomet’s head.

The statue itself is impressive: almost nine feet tall, and weighing in at around a ton. The horned idol sits on a throne adorned with a pentagram, but it is the idol’s wings, and not his chair, that curiously evoke the Iron Throne from a certain celebrated HBO fantasy series. He has the jarring horns of a virile ram but the biceps of a guy who lifts four or five times a week. His legs, which are crossed, end not in feet but in hooves. It might seem more menacing if not for the two bronze-statue children standing on either side of him — a girl on his left; a boy on his right; both are looking up at him earnestly.

“Baphomet contains binary elements symbolizing a reconciliation of opposites, emblematic of the willingness to embrace, and even celebrate differences,” Jex Blackmore, who organized the unveiling, told TIME late Sunday night. In a sense, the statue is a stress test of American plurality: at what point does religious freedom make the people uncomfortable?

Blackmore directs the Detroit chapter of the Satanic Temple, one of the few coherent organizations in a field that’s otherwise disorganized and dogmatically nebulous. The Satanic Temple has chapters in Florida and Finland, in Italy and Minneapolis. Its headquarters are in New York, but the Detroit office is its first and largest outpost. Blackmore — who, by the way, uses a pseudonym for safety reasons — grew up in the Detroit metropolitan area and returned to the city to work with the Satanic Temple after attending a lecture on Satanism at Harvard.

Asked whether her group is a religious organization (or rather an anti-religious organization) she explains that it’s less of a church and more of an affinity group, built around what she repeatedly refers to as “Satanic principles.” It’s not the dogma you might expect. To quote from the group’s website:

The Satanic Temple holds to the basic premise that undue suffering is bad, and that which reduces suffering is good. We do not believe in symbolic “evil.”

Most vitally, though, the group does not “promote a belief in a personal Satan.” By their logic, Satan is an abstraction, or, as Nancy Kaffer wrote for The Daily Beast last year, “a literary figure, not a deity — he stands for rationality, for skepticism, for speaking truth to power, even at great personal cost.”

Call it Libertarian Gothic, maybe — some darker permutation of Ayn Rand’s crusade for free will. One witnesses in the Satanic Temple militia a certain knee-jerk reaction to encroachments upon personal liberties, especially when those encroachments come with a crucifix in hand. The Baphomet statue is the Satanic Temple’s defiant retort du jour.

“We chose Baphomet because of its contemporary relation to the figure of Satan and find its symbolism to be appropriate if displayed alongside a monument representing another faith,” Blackmore said.

The monument she refers to is a six-foot marble slab engraved with the Ten Commandments, controversially situated on the grounds of the Oklahoma State Capitol. In 2012, state representative Mike Ritze fronted $10,000 out of his own pocket to have the marker installed in the shadow of the capitol’s dome, prompting the ire of those who believed it flagrantly violated the separation of church and state. The American Civil Liberties Union sued the state of Oklahoma; the Satanic Temple fought fire with fire. If the Christians could chisel their credo onto public property, the argument went, why couldn’t they?

The state didn’t agree, and rejected the Satanic Temple’s petition to place Baphomet’s statute on legislative property. The point is now moot, though: a month ago, the Oklahoma Supreme Court ruled that the Ten Commandments monument violated the state constitution, a judgment that will probably stick in spite of an obstinate governor.

It seems there are battles left to fight, though. A Detroit pastor described the unveiling of the statue as “a welcome home party for evil.” A Catholic activism group in the city actively encouraged people to attend mass at a local cathedral to speak out against the statue — a pray-in, if you will. Meanwhile, Arkansas Governor Asa Hutchinson recently signed a bill that will put the Ten Commandments on a similar monument on the grounds of the State Capitol in Little Rock. The Satanic Temple may be planning a road trip.

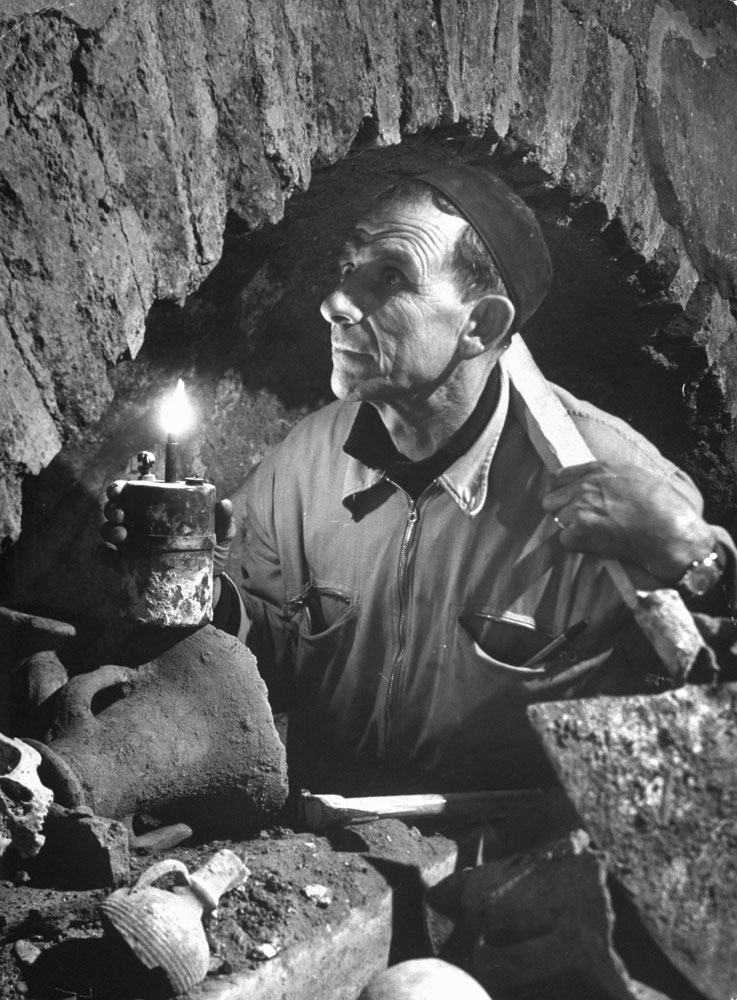

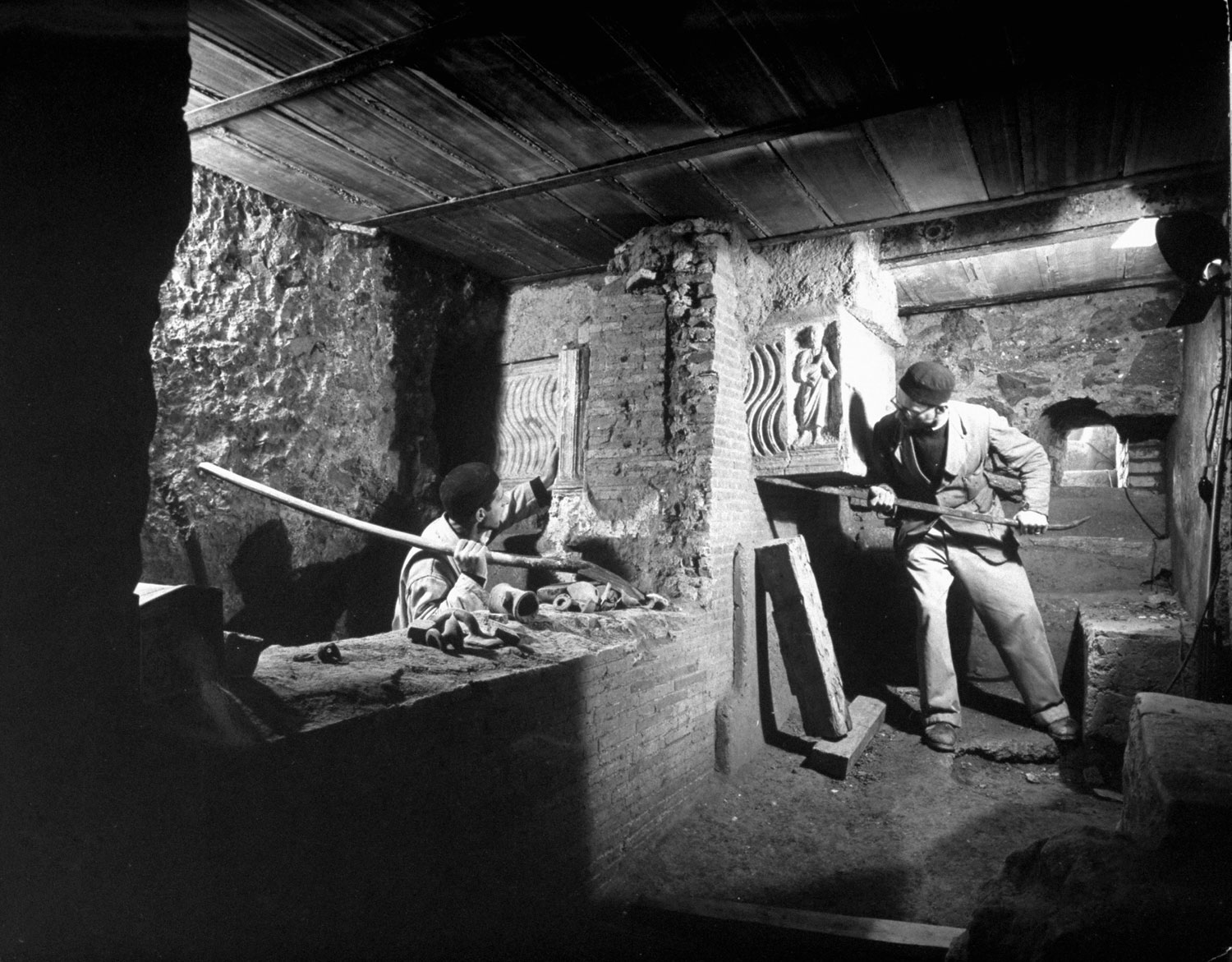

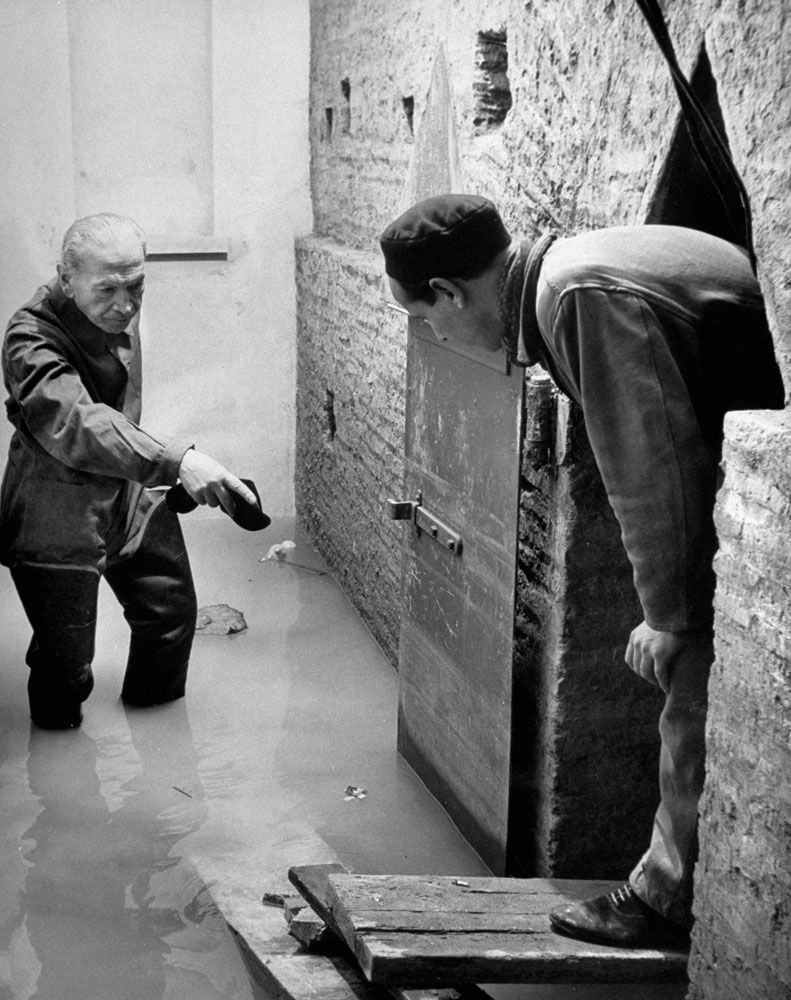

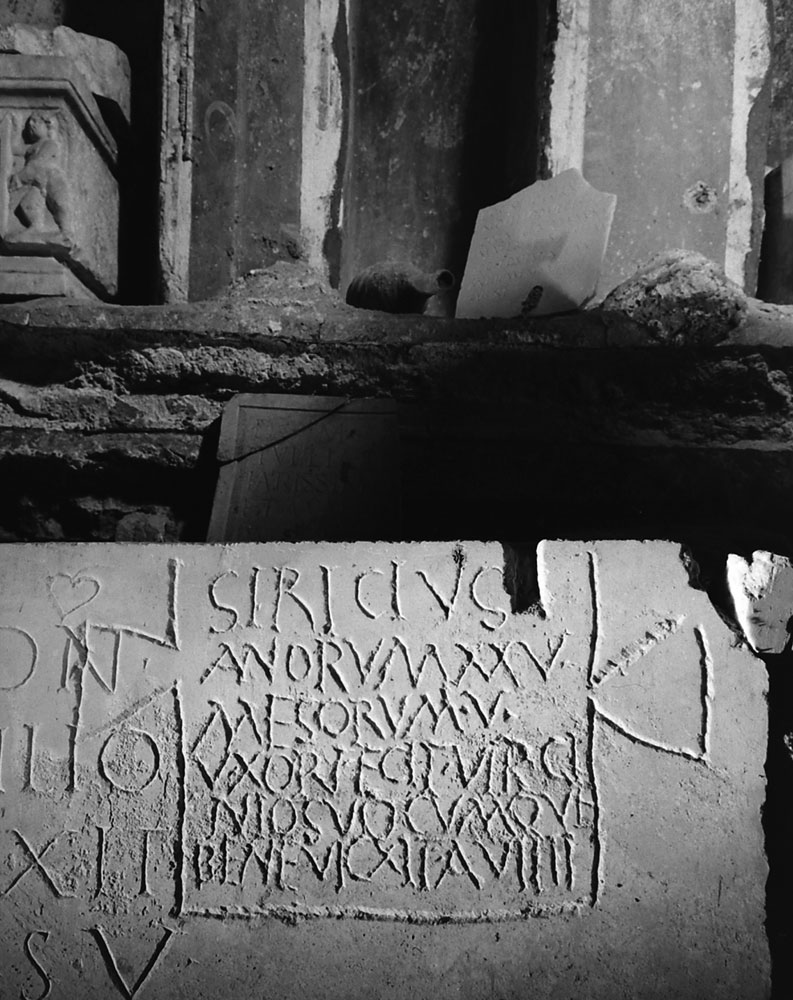

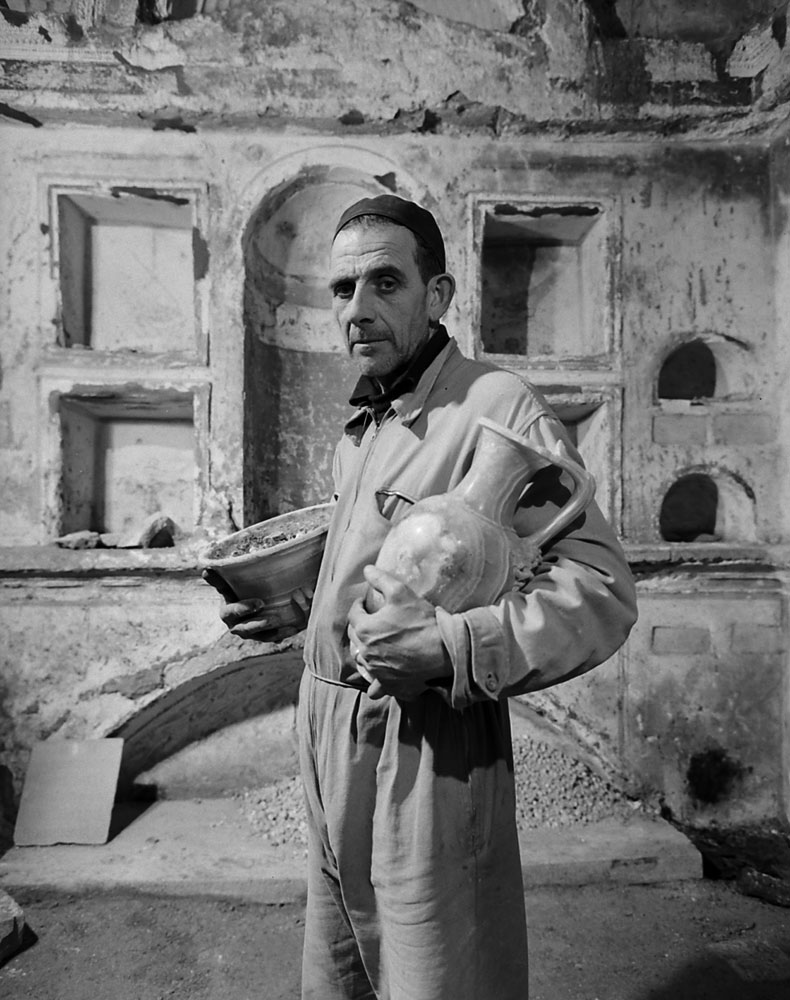

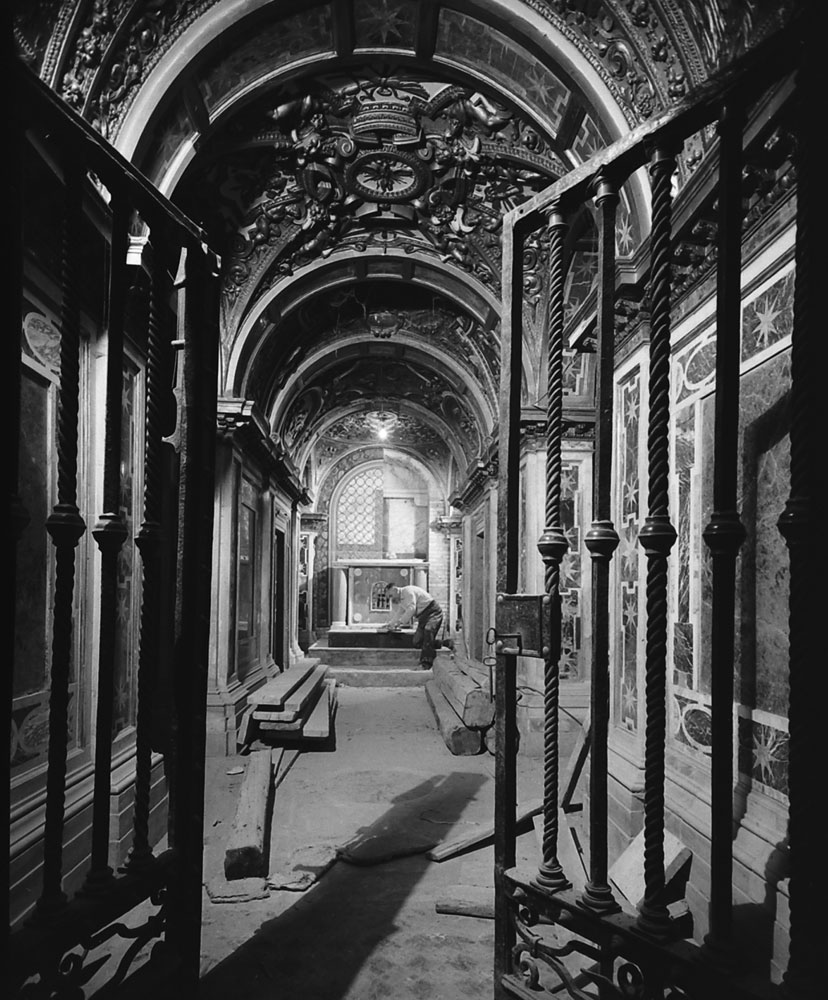

LIFE at the Vatican: Unearthing History Beneath St. Peter's

Read next: Preaching Pope Francis’s Politics May Be the Key to Becoming President

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com