It was on Aug. 17 of 1982, at a factory outside the city of Hanover in Germany, that the band ABBA received a very particular honor: According to Philips, the company that ran the factory, a CD of the band’s album The Visitors was pressed that day. And it wasn’t just any CD—it was the first CD ever manufactured. The new technology would go on sale in Japan later that year, and in other markets around the world the following March.

Though CD players at the time cost hundreds of dollars—up to $1,000 when TIME reported on their introduction to the U.S. market, though competition was expected to more than halve their cost quickly—manufacturers were confident they’d be a hit. (CDs themselves sold for about $17 at the time, which is the same as about $40 in today’s dollars.) One of their big advantages was the sound quality they promised, as the article explained:

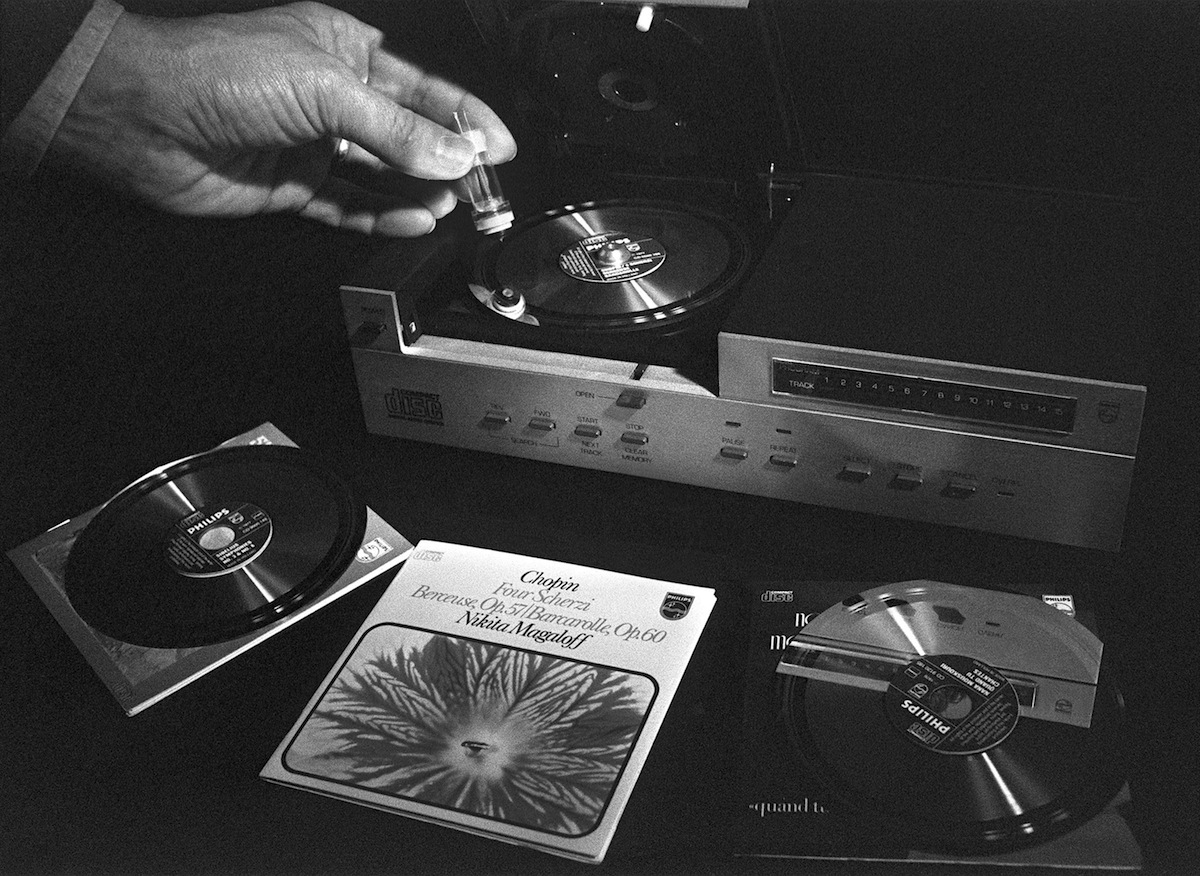

Until digital, record technology had not changed much in principle since the Edison cylinder. On conventional LPs, called analog recordings, images of sound waves picked up by a microphone are traced into vinyl grooves; a kind of aural photograph is “developed” when a stylus retraces the grooves and re-creates the sonic vibrations. Digital recordings are akin to the computer-assisted cameras used in space, which translate images into a series of binary numbers that are later reassembled into pictures back on earth. In digital recording a computer takes 44,000 impressions of sound per sec. and assigns each a numerical value. The numbers are then recorded in pits embedded in the disc, read by a laser beam and changed back into sound. The “digital” LPs currently found in record stores are really hybrids, recorded digitally but pressed and played back as analog discs.

Digital CDs have several important advantages over conventional records. For one thing, there is no surface noise, since the laser reads only the numbers, not any dust or grime on the disc’s laminated surface. Because nothing touches the disc, there is no wear. Digital records lack the distortion customarily found on LPs in loud passages and near the end of a side, when the sound is unnaturally compressed. The new players are designed to plug into conventional component systems, and the discs will be compatible with any player on the market.

The real advance, however, may turn out to be artistic. Because of the clarity of digital sound, every flaw, both in performance and production, is ruthlessly exposed. One probable result: pop-record producers will be more careful with such studio gimmicks as overdubbing and excessive reverberation. In the classical sphere, an even higher premium will be put on technical excellence.

Of course, today’s music fans may read those paragraphs with a laugh. Studio gimmicks are alive and kicking — and vinyl records, the kind TIME poo-pooed back in the ’80s, are having a resurgence. One major reason? Sound quality.

Read more, here in the TIME Vault: Here Come CDs

Read more: On its 50th birthday, the cassette tape is still rolling

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com