The first nude print ad was published in 1936 for Woodbury Soap. It featured an undressed woman lazily lying at the beach, her arm positioned at just the right angle to shield her breasts from view. It followed the old advertising adage that sex sells.

But that no longer holds true, according to a new study released by the Psychological Bulletin. Brad Bushman, a communications professor at Ohio State University and a co-author of the study, says it’s not that sex and violence don’t grab our attention—of course they do. In fact, paying attention to such things are evolutionary responses that are necessary for survival (being attuned to safety threats prepares people to protect themselves; finding opportunities for mating keep the species going).

But just because they grab our eye doesn’t mean the ad translates into sales.

“[A]dvertisers think sex and violence sell, so they buy advertising time during sexual and violent programs, and in turn producers continue to create sexual and violent programs that attract advertising revenue,” the authors write. But when a person is being shown a product—say, laundry detergent—with a sexy backdrop, it’s not the detergent that’s capturing the attention so much as the action onscreen. Sex is distracting, Bushman says. “We have a limited capacity to pay attention to cues.”

Bushman and his co-author, Robert Lull, found 1,869 articles in two databases that had historically studied consumer response to sex and violence. Researchers weeded out studies that didn’t directly address consumer response, didn’t have a control group, and didn’t look explicitly at the effects of sex and/or violence on the consumer.

“In the best case scenario, sex and violence doesn’t work,” Bushman told TIME. “For advertisers, it can actually backfire, and people will be less likely to remember your [product]. They might report being less likely to buy your product if the content of your program is violent or sexual.”

No surprise, some demographics respond differently to sexy or violent ads. Women tend to remember products from provocative ads; men tend to be distracted by sex or violence and not remember the product. Older participants were turned off by violence and sex; younger consumers were more likely to respond to it.

Still, taken together, the researchers conclude this: “Brands advertised in violent contexts will be remembered less often, evaluated less favorably, and less likely to be purchased than brands advertised in nonviolent media.”

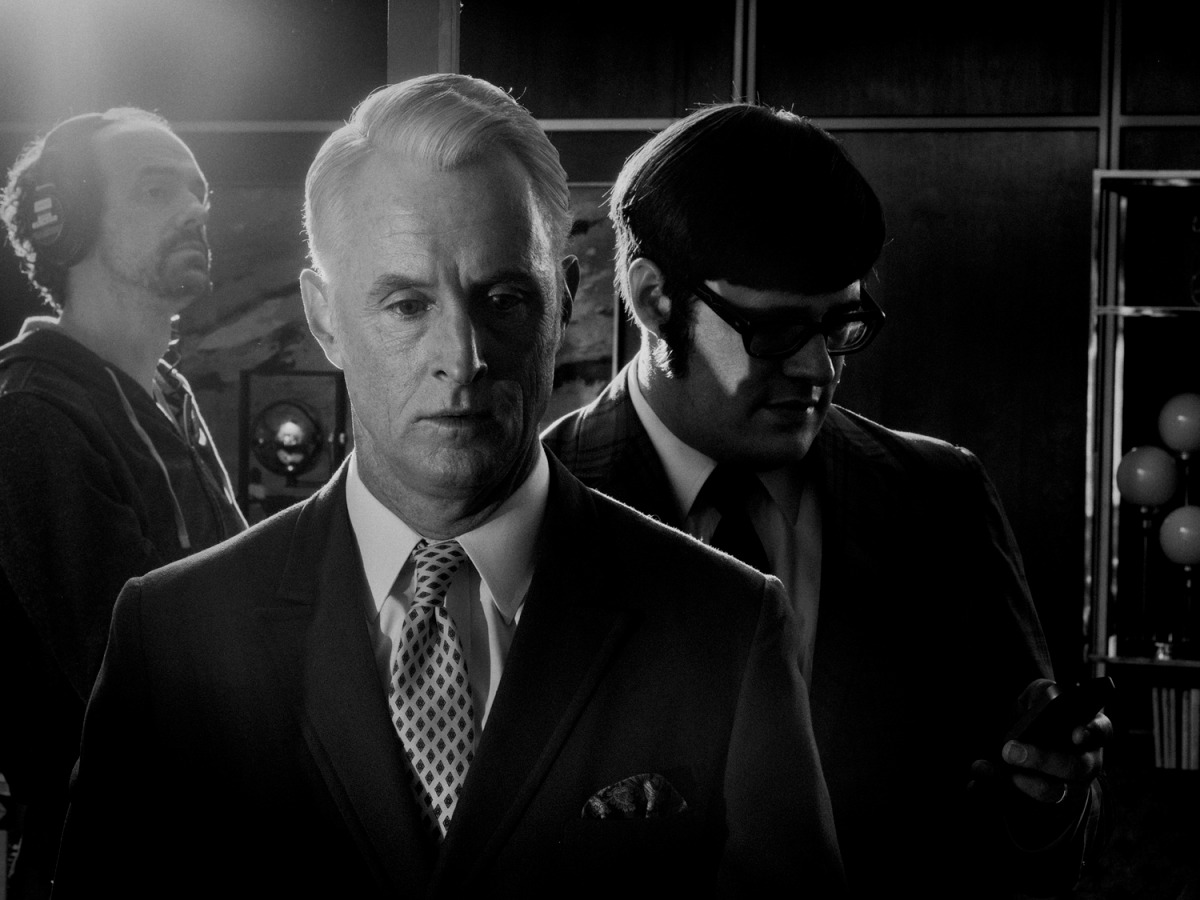

'Mad Men' Up Close: Photos From the Set of the Celebrated Show

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Tanya Basu at tanya.basu@time.com