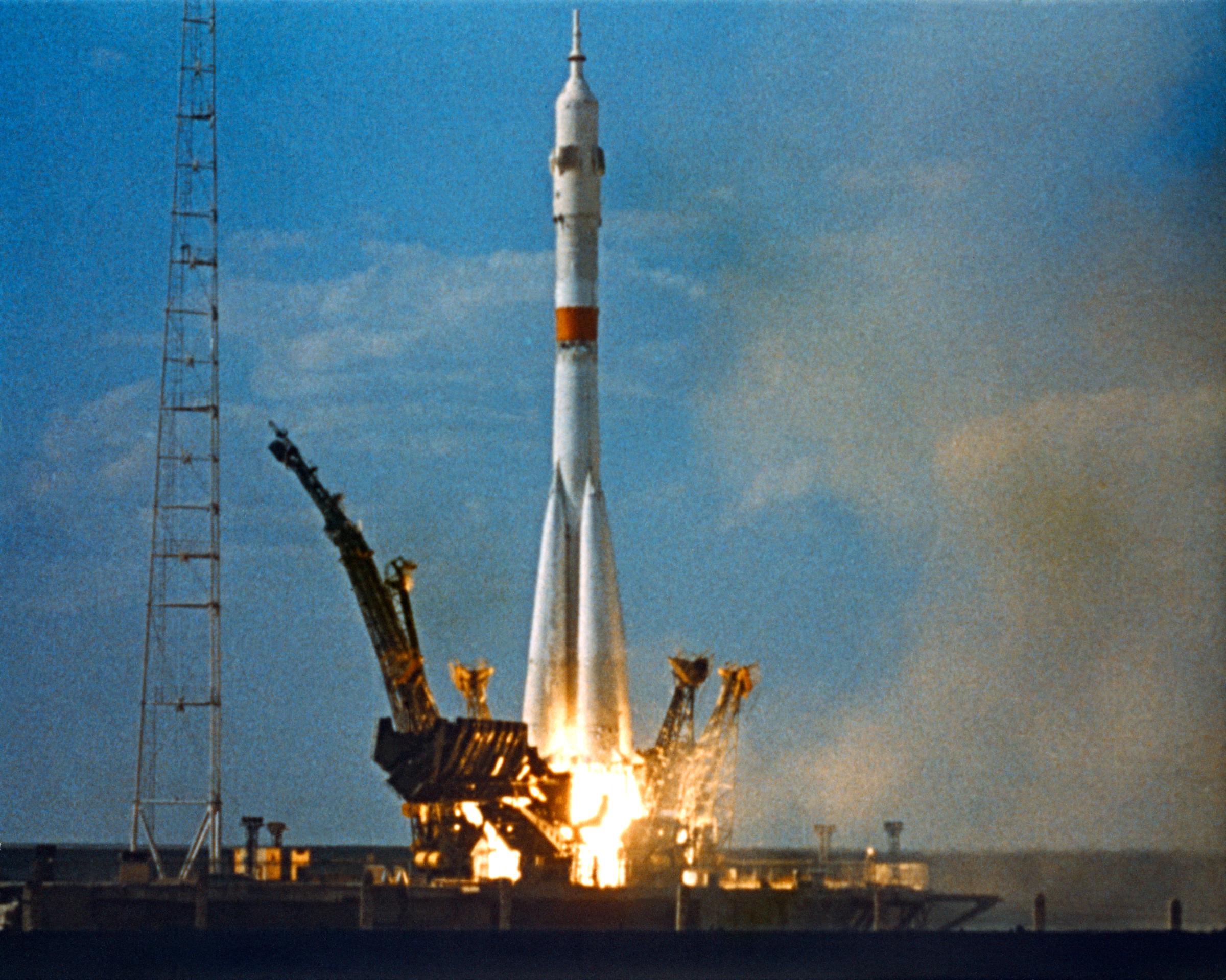

In addition to reaching distant Pluto, there was another significant celestial event this week. It was an anniversary that needs to be remembered, not only for its historical importance but also for its significance as a model for collaboration in space in the 21st century. Forty years ago, the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project signaled the first international human spaceflight—a by-product of mutual trust between the U.S. and the then-Soviet Union and a blend of technological wherewithal, and, of course, sky-high politics.

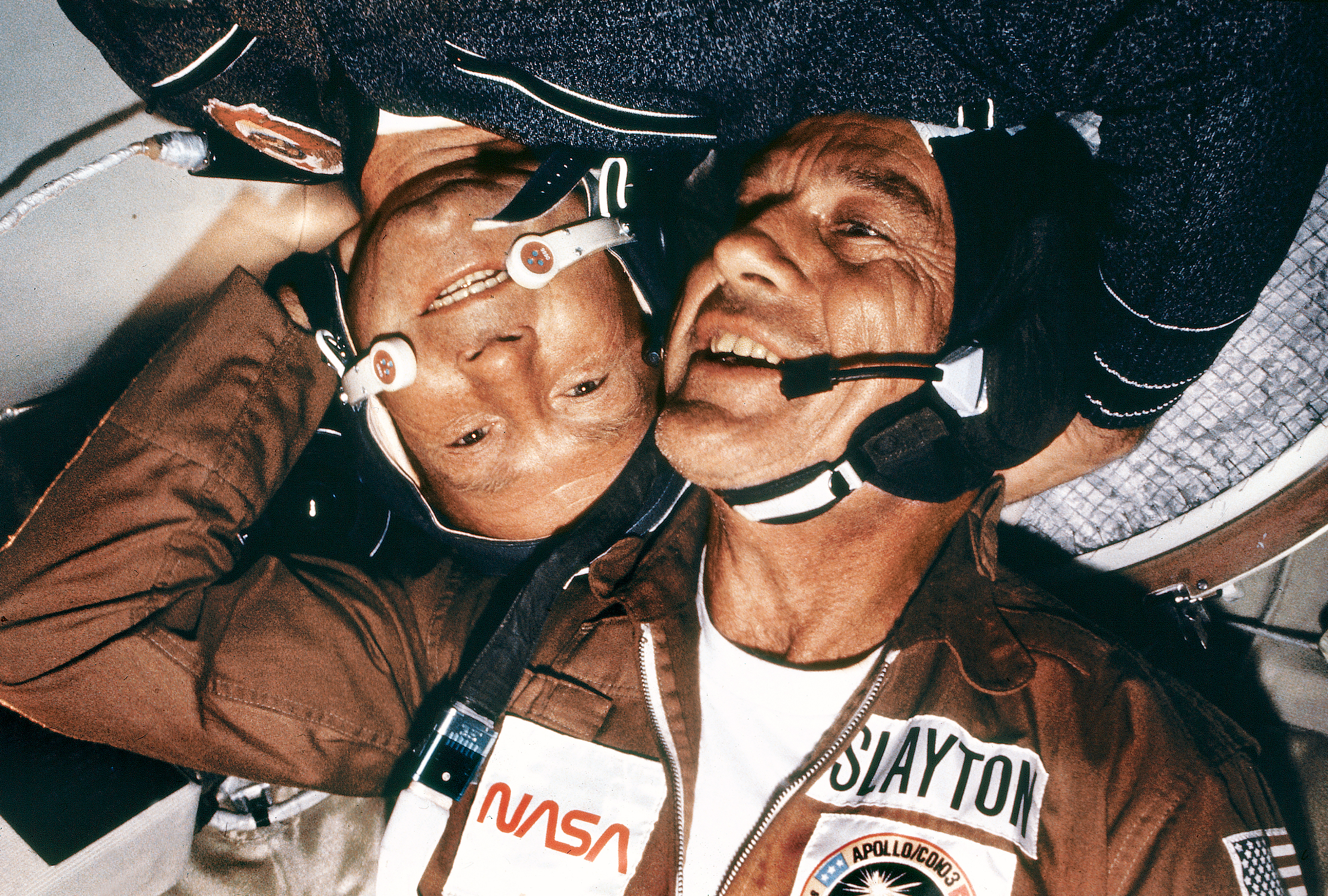

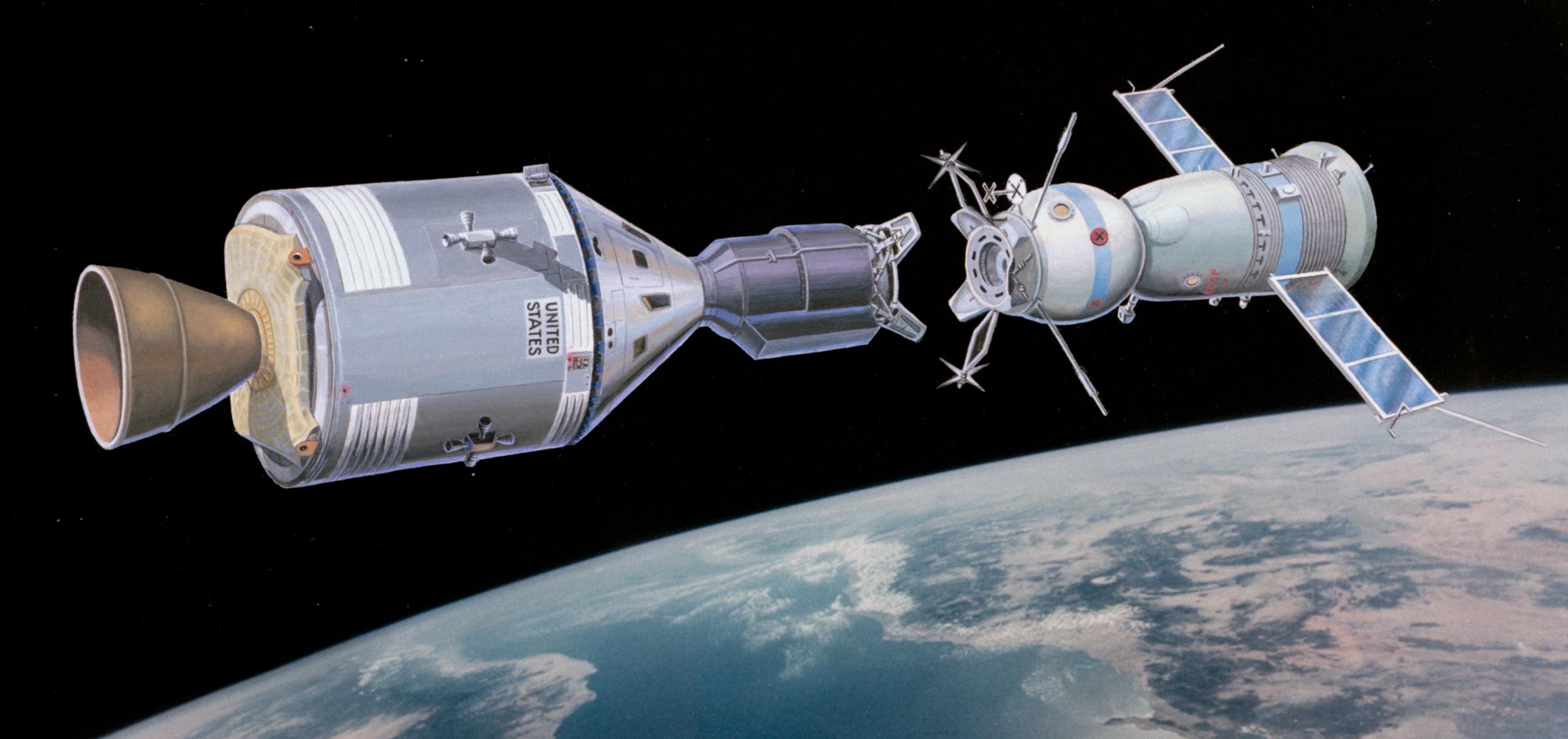

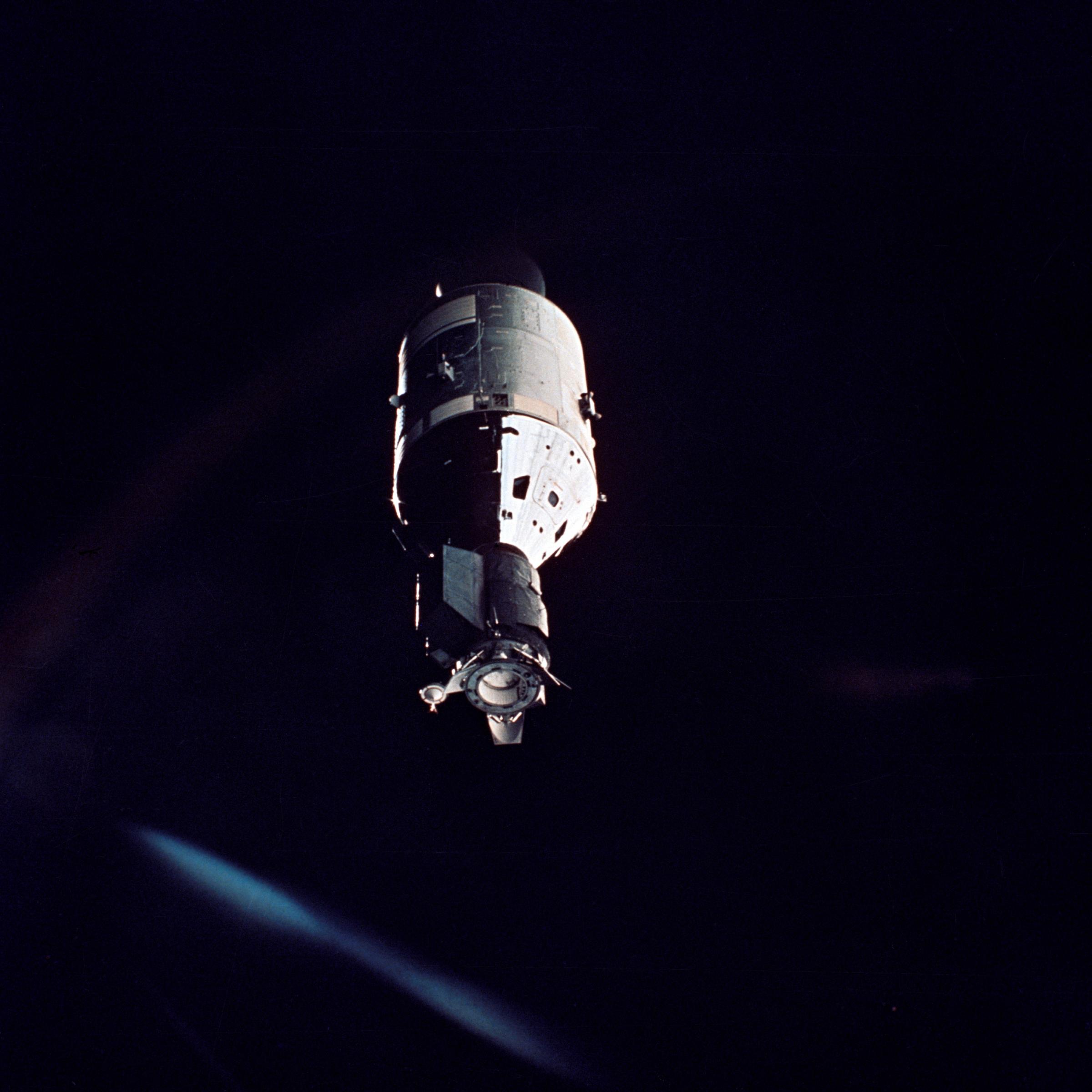

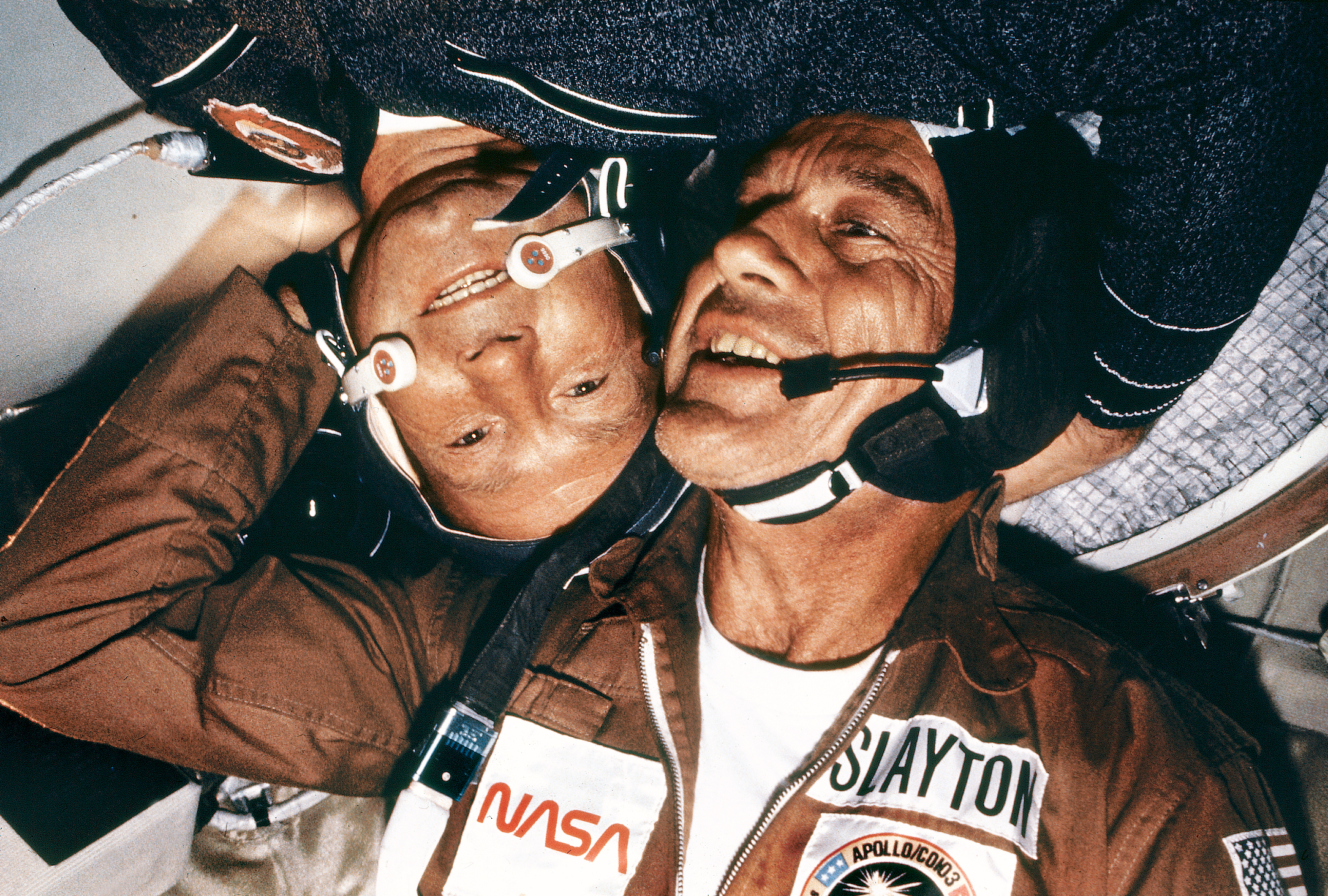

On July 17, 1975, a NASA Apollo spacecraft carrying three astronauts linked up with a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft and its two-person cosmonaut crew. After the famous “handshake in space,” the Soviet cosmonauts and U.S. astronauts worked on joint experiments. From a technical standpoint, that history-making mission sharpened engineering expertise on both sides, making possible following joint space flights, specifically the Space Shuttle–Mir Program and today’s International Space Station.

That nine-day Apollo-Soyuz mission was a game-changer, bringing together two adversaries during the Cold War and the often-called “Space Race.” The competition between the U.S. and the Soviet Union was, in my view, left in the lunar dust when Neil Armstrong and I firmly planted our boots years earlier on the time-weathered Moon. Our “one small step” translated into a U.S. victory at the lunar goal line. Nevertheless, our nation’s space program represented then—and more so today—a tool to forge international partnerships not only in Earth orbit … but also beyond.

See Photos From the Historic Apollo-Soyuz Mission

One such partnership could be with China, a country that is ramping up its prowess in human and robotic space exploration. I’ve personally met with Chinese astronauts, and in my conversations with them, it’s clear that they have an agenda to use their own space facilities in Earth orbit to explore the Moon with robots and humans, and dispatch spacecraft to Mars.

I was heartened to see recent movement in opening up U.S.-China discussion on a number of space-related matters. In June, Secretary of State John Kerry took active part in the seventh round of the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue in Washington, D.C. American and Chinese officials addressed a set of important bilateral, regional, and global issues.

More than 70 important outcomes resulted from the dialogue. Among the topics were space security, satellite collision avoidance, weather monitoring, climate research, and establishing regular civil space cooperation consultations. To that last point, the U.S. and China decided to establish regular bilateral government-to-government consultations on civil space cooperation. The first U.S.-China Civil Space Cooperation Dialogue is to take place in China before the end of October.

This is an important, perhaps seminal, window of opportunity. As I’ve written in TIME, I encourage movement toward an invite to have Chinese space travelers visit the International Space Station, and I envision American astronauts and commercial space firms sojourning to Chinese laboratories in Earth orbit. Not only would such agreements help bolster U.S. leadership in space, but it would also set in motion the prospect of other joint space initiatives at the Moon and other destinations, above all, the planet Mars.

So let’s look back and build upon Apollo-Soyuz, a signature element of space cooperation that demonstrated a dramatic shift in U.S. policy from competition to détente. Apollo-Soyuz signaled a dramatic shift in space activities and the recognition that space was a finite and sensitive environment in which the activities of one nation could potentially destroy the ability of all nations to utilize space for peaceful purposes. Cooperation with China could lead to a similar realization by the many new entrants to the community of space-faring nations.

It is my conviction that the real objective of cooperation with China should be working together to settle Mars. Both nations, and other countries, need to learn together and sharpen their space skills to advance such a great collaborative adventure. Doing so would build upon the legacy of Apollo-Soyuz, a history-making mission that set in motion the optimistic and promising quest to explore space for all humankind.

Buzz Aldrin, best known for his Apollo 11 moonwalk, holds a doctoral degree in astronautics and continues to wield influence as an international advocate of space science and planetary exploration. Aldrin and co-author, Leonard David, wrote Mission to Mars – My Vision for Space Exploration, published in 2013 by the National Geographic Society. Aldrin’s new children’s book, Welcome to Mars: Making a Home on the Red Planet, co-authored with Marianne Dyson, is available in September.

Time is following the yearlong mission between American astronaut Scott Kelly and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko, who are 111 days into a yearlong mission aboard the international space station. Click here to watch the series, or watch Episode 1, “Leaving Home,” below.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com